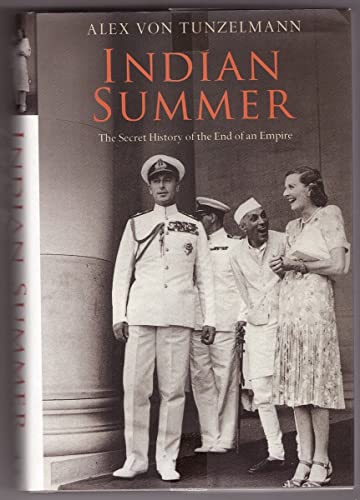

Indian Summer: The Secret History of the End of an Empire - Hardcover

The last days of the British Raj. The end of empire. A love affair between Edwina Mountbatten, wife of the last British viceroy to India, and Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister.

The stroke of midnight on 15 August 1947 liberated 400 million people from the British Empire. With the loss of India, its greatest colony, a nation admitted it was no longer a superpower, and a king ceased to sign himself Rex Imperator.

It was one of the defining moments of world history, but it had been brought about by a tiny group of people. Among them were Jawaharlal Nehru, the fiery Indian prime minister with radical plans for a socialist revolution; Mohammed Ali Jinnah, the Muslim leader who would stop at nothing to establish the world’s first modern Islamic state; Mohandas Gandhi, the mystical figure who enthralled a nation; and Louis and Edwina Mountbatten, the glamorous but unlikely couple who had been dispatched to get Britain out of India without delay. Within hours of the midnight chimes, the two new nations of India and Pakistan would descend into anarchy and terror. Nehru, Jinnah, Gandhi and the Mountbattens struggled with public and private turmoil while their dreams of freedom and democracy turned to chaos, bloodshed, genocide and war.

Indian Summer depicts the epic sweep of events that ripped apart the greatest empire the world has ever seen, and saw one million people killed and ten million dispossessed. It reveals the secrets of the most powerful players on the world stage: the Cold War conspiracies, the private deals, and the intense and clandestine love affair between the wife of the last viceroy and the first prime minister of free India.

The stroke of midnight on 15 August 1947 liberated 400 million people from the British Empire. With the loss of India, its greatest colony, a nation admitted it was no longer a superpower, and a king ceased to sign himself Rex Imperator.

It was one of the defining moments of world history, but it had been brought about by a tiny group of people. Among them were Jawaharlal Nehru, the fiery Indian prime minister with radical plans for a socialist revolution; Mohammed Ali Jinnah, the Muslim leader who would stop at nothing to establish the world’s first modern Islamic state; Mohandas Gandhi, the mystical figure who enthralled a nation; and Louis and Edwina Mountbatten, the glamorous but unlikely couple who had been dispatched to get Britain out of India without delay. Within hours of the midnight chimes, the two new nations of India and Pakistan would descend into anarchy and terror. Nehru, Jinnah, Gandhi and the Mountbattens struggled with public and private turmoil while their dreams of freedom and democracy turned to chaos, bloodshed, genocide and war.

Indian Summer depicts the epic sweep of events that ripped apart the greatest empire the world has ever seen, and saw one million people killed and ten million dispossessed. It reveals the secrets of the most powerful players on the world stage: the Cold War conspiracies, the private deals, and the intense and clandestine love affair between the wife of the last viceroy and the first prime minister of free India.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Alex von Tunzelmann was born in 1977 and lives in London, England. Since leaving Oxford, where she read history and edited both Cherwell and Isis, she has worked primarily as a researcher. She has contributed to books as diverse as The Political Animal by Jeremy Paxman, The Truth About Markets by John Kay, Does Education Matter? by Alison Wolf, and Not on the Label by Felicity Lawrence. She has been recognized for her writing in several national competitions, ranging from the Vogue Talent Contest to the Financial Times Young Business Writer of the Year. Most recently, Alex has collaborated with Jeremy Paxman on his new book, On Royalty.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

On a warm summer night in 1947, the largest empire the world has ever seen did something no empire had done before. It gave up. The British Empire did not decline, it simply fell; and it fell proudly and majestically on to its own sword. It was not forced out by revolution, nor defeated by a greater rival in battle. Its leaders did not tire or weaken. Its culture was strong and vibrant. Recently it had been victorious in the century’s definitive war.

When midnight struck in Delhi on the night of 14 August 1947, a new, free Indian nation was born. In London, the time was 8.30 p.m. The world’s capital could enjoy another hour or two of a warm summer evening before the sun literally and finally set on the British Empire.

The constituent assembly of India was convened at that moment in New Delhi, a monument to the self-confidence of the British government, which had built its new capital on the site of seven fallen cities. Each of the seven had been built to last for ever. And so was New Delhi, a colossal arrangement of sandstone neoclassicism and wide boulevards lined with banyan trees. Seen from the sky, the interlocking series of avenues and roundabouts formed a pattern like the marble trellises of geometric stars that ventilated Mughal palaces. New Delhi was India, but constructed — and, they thought, improved upon — by the British. The French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau had laughed when he saw the new city half-built in 1920, and observed: ‘Ça sera la plus magnifique de toutes ces ruines.’

Inside the chamber of the constituent assembly on the night of 14 August 1947, 2000 princes and politicians from across the 1.25 million square miles that remained of India sat together on parliamentary benches. Yet amid all the power and finery, two persons were conspicuous by their absence. One was Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the leader of the Muslim League, who was in one of those parts of the Empire that had just become Pakistan. His absence signified the partition of the subcontinent, the split which had ripped two wings off the body of India and called them West and East Pakistan (later Pakistan and Bangladesh), creating Muslim homelands separate from the predominantly Hindu mass of the territory. The other truant was Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, who was sound asleep in a smashed-up mansion in a riot-torn suburb of Calcutta.

Gandhi’s absence was a worrying omen. The seventy-seven-year-old Mahatma, or ‘great soul’, was the most famous and the most popular Indian since Buddha. Regarded as little short of a saint among Christians as well as Hindus, he had been a staunch defender of the British Empire until the 1920s. Since then, he had campaigned for Indian self-rule. Many times it had been almost within his grasp: in 1922, 1931, 1942, 1946. Each time he had let it go. Now, finally, India was free, but that had nothing to do with Gandhi — and Gandhi would have nothing to do with it.

In the chamber the dignitaries fell silent as the foremost among them, Jawaharlal Nehru, stepped up to make one of the most famous speeches in history. At fifty-seven years old, Nehru had grown into his role as India’s leading statesman. His last prison term had finished exactly twenty-six months before. The fair skin and fine bone structure of an aristocratic Kashmiri Brahmin was rendered approachable by a ready smile and warm laugh. Dark, sleepy, soulful eyes belied a quick wit and quicker temper. In him were all the virtues of the ancient nation, filtered through the best aspects of the British Empire: confidence, sophistication, and charisma. ‘Long years ago,’ he began, ‘we made a tryst with destiny. And now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge; not wholly or in full measure, but substantially. At the stroke of the midnight hour, while the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom.’ The clock struck and, in that instant, he became the new country’s first Prime Minister. The reverential mood in the hall was broken abruptly by an unexpected honk from the back. The dignitaries jerked their heads round to the source of the sound, and a look of relief passed over their faces as they saw a devout Hindu member of the assembly blowing into a conch shell — an invocation of the gods. Mildred Talbot, a journalist who was present, noticed that the interruption had not daunted the new Prime Minister. ‘When I happened to spot Nehru just as he was turning away, he was trying to hide a smile by covering his mouth with his hand.’

It was the culmination of a lifetime’s struggle; and yet, as Nehru later confided to his sister, his mind had not been on the splendid words. A few hours before, he had received a telephone call from Lahore in what was about to become West Pakistan. It was his mother’s home town, and a place where he had spent much of his childhood.4 Now it was being torn apart. Gangs of Muslims and Sikhs had clashed in the streets. The main gurdwara — the Sikh temple — was ablaze. One hundred thousand people were trapped inside the city walls without water or medical assistance. Violence was a much-predicted consequence of the handover, but preparations for dealing with it had been catastrophically inadequate. The only help available in Lahore was from 200 Gurkhas, stationed nearby, under the command of an inexperienced British captain who was only twenty years old. They had little chance of stopping the carnage. The horror of that night in Lahore set the tone for weeks of bloodshed and destruction. Perhaps the Hindu astrologers had been right when they had declared 14 August to be an inauspicious date. Or perhaps the Viceroy’s curious decision to rush independence through ten months ahead of the British government’s schedule was to blame.

Emerging into the streets of Delhi, Nehru was greeted by the ringing of temple bells, the bangs and squeals of fireworks and the happy shouting of crowds. Guns were fired, in celebration rather than in anger; an effigy of British imperialism was burned, in both. . . .

When midnight struck in Delhi on the night of 14 August 1947, a new, free Indian nation was born. In London, the time was 8.30 p.m. The world’s capital could enjoy another hour or two of a warm summer evening before the sun literally and finally set on the British Empire.

The constituent assembly of India was convened at that moment in New Delhi, a monument to the self-confidence of the British government, which had built its new capital on the site of seven fallen cities. Each of the seven had been built to last for ever. And so was New Delhi, a colossal arrangement of sandstone neoclassicism and wide boulevards lined with banyan trees. Seen from the sky, the interlocking series of avenues and roundabouts formed a pattern like the marble trellises of geometric stars that ventilated Mughal palaces. New Delhi was India, but constructed — and, they thought, improved upon — by the British. The French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau had laughed when he saw the new city half-built in 1920, and observed: ‘Ça sera la plus magnifique de toutes ces ruines.’

Inside the chamber of the constituent assembly on the night of 14 August 1947, 2000 princes and politicians from across the 1.25 million square miles that remained of India sat together on parliamentary benches. Yet amid all the power and finery, two persons were conspicuous by their absence. One was Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the leader of the Muslim League, who was in one of those parts of the Empire that had just become Pakistan. His absence signified the partition of the subcontinent, the split which had ripped two wings off the body of India and called them West and East Pakistan (later Pakistan and Bangladesh), creating Muslim homelands separate from the predominantly Hindu mass of the territory. The other truant was Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, who was sound asleep in a smashed-up mansion in a riot-torn suburb of Calcutta.

Gandhi’s absence was a worrying omen. The seventy-seven-year-old Mahatma, or ‘great soul’, was the most famous and the most popular Indian since Buddha. Regarded as little short of a saint among Christians as well as Hindus, he had been a staunch defender of the British Empire until the 1920s. Since then, he had campaigned for Indian self-rule. Many times it had been almost within his grasp: in 1922, 1931, 1942, 1946. Each time he had let it go. Now, finally, India was free, but that had nothing to do with Gandhi — and Gandhi would have nothing to do with it.

In the chamber the dignitaries fell silent as the foremost among them, Jawaharlal Nehru, stepped up to make one of the most famous speeches in history. At fifty-seven years old, Nehru had grown into his role as India’s leading statesman. His last prison term had finished exactly twenty-six months before. The fair skin and fine bone structure of an aristocratic Kashmiri Brahmin was rendered approachable by a ready smile and warm laugh. Dark, sleepy, soulful eyes belied a quick wit and quicker temper. In him were all the virtues of the ancient nation, filtered through the best aspects of the British Empire: confidence, sophistication, and charisma. ‘Long years ago,’ he began, ‘we made a tryst with destiny. And now the time comes when we shall redeem our pledge; not wholly or in full measure, but substantially. At the stroke of the midnight hour, while the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom.’ The clock struck and, in that instant, he became the new country’s first Prime Minister. The reverential mood in the hall was broken abruptly by an unexpected honk from the back. The dignitaries jerked their heads round to the source of the sound, and a look of relief passed over their faces as they saw a devout Hindu member of the assembly blowing into a conch shell — an invocation of the gods. Mildred Talbot, a journalist who was present, noticed that the interruption had not daunted the new Prime Minister. ‘When I happened to spot Nehru just as he was turning away, he was trying to hide a smile by covering his mouth with his hand.’

It was the culmination of a lifetime’s struggle; and yet, as Nehru later confided to his sister, his mind had not been on the splendid words. A few hours before, he had received a telephone call from Lahore in what was about to become West Pakistan. It was his mother’s home town, and a place where he had spent much of his childhood.4 Now it was being torn apart. Gangs of Muslims and Sikhs had clashed in the streets. The main gurdwara — the Sikh temple — was ablaze. One hundred thousand people were trapped inside the city walls without water or medical assistance. Violence was a much-predicted consequence of the handover, but preparations for dealing with it had been catastrophically inadequate. The only help available in Lahore was from 200 Gurkhas, stationed nearby, under the command of an inexperienced British captain who was only twenty years old. They had little chance of stopping the carnage. The horror of that night in Lahore set the tone for weeks of bloodshed and destruction. Perhaps the Hindu astrologers had been right when they had declared 14 August to be an inauspicious date. Or perhaps the Viceroy’s curious decision to rush independence through ten months ahead of the British government’s schedule was to blame.

Emerging into the streets of Delhi, Nehru was greeted by the ringing of temple bells, the bangs and squeals of fireworks and the happy shouting of crowds. Guns were fired, in celebration rather than in anger; an effigy of British imperialism was burned, in both. . . .

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherMcClelland & Stewart

- Publication date2007

- ISBN 10 0771087411

- ISBN 13 9780771087417

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages480

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 78.80

Shipping:

US$ 23.00

From Canada to U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Indian Summer: The Secret History of the End of an Empire Tunzelmann, Alex von

Published by

McClelland & Stewart

(2007)

ISBN 10: 0771087411

ISBN 13: 9780771087417

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 2

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # XL-202

Buy New

US$ 78.80

Convert currency