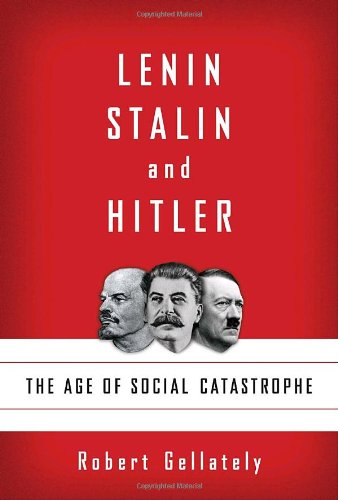

Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe - Hardcover

In a groundbreaking work, Gellately makes clear that most comparative studies of the Soviet and Nazi dictatorships are undermined by neglecting the key importance of Lenin in the unfolding drama. Rejecting the myth of the “good” Lenin, the book provides a convincing social-historical account of all three dictatorships and carefully documents their similarities and differences. It traces the escalation of conflicts between Communism and Nazism, and particularly of the role of Hitler’s anathema against what he called “Jewish Bolshevism.” The book shows how the vicious rivalry between Stalin and Hitler led inescapably to a war of annihilation and genocide. The reverberations of this gargantuan struggle are felt everywhere to this day.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

The First World War strained the regime of Tsar Nicholas II to the breaking point. Initially, in August 1914, the nation rallied around the flag. Politicians and the urban middle classes welcomed the war, and the army went off to defend their “Slavic brothers” in Yugoslavia against German and Austrian aggression. The Duma, Russia’s national assembly, dissolved itself to symbolize the country’s support of the government. But no one in Europe, let alone in Russia, visualized the war to come, the devastation it would cause, and how long hostilities would last.

The tsarist empire had the largest army in Europe but lacked the resources to fight a prolonged struggle. Before the first year of the fighting was over, there were shortages of all kinds. Replacement troops were being trained without rifles and sent onto the battlefield, where they were to go among the dead and wounded to pick up the weapons they needed.

By the beginning of 1917, widespread discontent over the ghastly sacrifices of the war, food shortages, and high prices led to bitter strikes and hostile demonstrations. A police report for January 1917 from Petrograd, the newly renamed capital, spelled out the darkening situation: “These mothers, exhausted from standing endlessly in lines and having suffered so much watching their half-starving and sick children, are perhaps much closer to a revolution than Messrs. Miliukov, Rodichev, and Co. [leaders of the liberal Kadet Party], and of course much more dangerous.”[1]

The pent-up resentments and grievances were ignited by a demonstration in the capital on February 23, when a peaceful march for women’s rights was joined by striking workers. Cries rang out for bread, and people exclaimed, “Down with the tsar!” By February 26, under orders from the tsar, troops fired on demonstrators. Some of the soldiers were sickened by what they did, and then the next day the revolution began as mutinous troops rampaged through the streets killing or disarming police. Crowds shouting “Give us bread,” “Down with the war,” “Down with the Romanovs,” and “Down with the government” attacked police headquarters.

Instead of charging the crowds, tens of thousands of peasant soldiers, their mentality shaped by decades of grievances against the system, went over to the people. Together they exploded in a mixture of rage and revenge that rumbled on for days. The police put machine guns atop buildings, but even these were ineffective against the angry tumult.[2]

Tsar Nicholas II was informed, and on March 2, in a meeting at the front, Aleksandr Guchkov and Vasily Shulgin, deputies of the State Duma, laid out the stark options. Guchkov pronounced the home front and military out of control. The situation was not “the result of some conspiracy,” but represented “a movement that sprang from the very ground and instantly took on an anarchical cast and left the authorities fading into the background.”

The upheaval had spread to the army, “for there isn’t a single military unit that isn’t immediately infected by the atmosphere of the movement.” Guchkov believed that it might be possible to prevent the inevitable if a radical step was taken. He explained:

"The people profoundly believe that the situation was caused by the mistakes of those in authority, in particular the highest authority, and this is why some sort of act is needed that would work upon the popular consciousness. The only path is to transfer the burden of supreme rulership to other hands. Russia can be saved, the monarchical principle can be saved, the dynasty can be saved. If you, Your Majesty, announce that you are transferring your power to your little son, if you assign the regency to Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich, and if in your name or in the name of the regent instructions are issued for a new government to be formed, then perhaps Russia will be saved. I say perhaps because events are unfolding so quickly."[3]

Dismayed at this turn of events, Nicholas II accepted the inevitable, and on March 3, 1917, he abdicated, also in the name of his gravely ill son. The tsar stepped down in favor of his brother Grand Duke Mikhail, who tried to get assurances of support in the capital. He asked leading figures from the Duma, including Prince Georgii Lvov, Mikhail Rodzianko, and Alexander Kerensky, whether they could vouch for his safety if he accepted the crown. None thought they could, so Mikhail was left with little choice but to refuse the crown.[4] In fact a third of the members of the State Duma formed a “provisional committee” on the afternoon of February 27, and by March 2, with the tsar’s abdication, that became the new provisional government.[5]

The American ambassador in Petrograd witnessed what he regarded as “the most amazing revolution.” He reported that a nation of 200 million living under an absolute monarchy for a thousand years had forced out their emperor with a minimal amount of violence. The three-hundred-year rule of the Romanov dynasty was over.[6] In fact the revolution was not “bloodless,” for in Petrograd alone estimates of the new government put the killed or wounded at 1,443. Even the higher figures mentioned were small in comparison with what was to follow.[7]

LENIN AND THE BOLSHEVIKS

The main Marxist party, the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (RSDLP), including the Bolshevik and Menshevik factions, had nothing to do with this liberal revolution that swept away the Romanovs. Lenin was in Switzerland. Stalin was isolated in western Siberia, in exile since 1913. Most other top Bolshevik and Menshevik leaders were far removed from the action as well, with Leon Trotsky and Nikolai Bukharin five thousand miles away in North America.

But just over seven months after the February liberal revolution, the world learned of the October Communist revolution, headed by Lenin and the Bolsheviks. It was to change the course of world history, and the twentieth century was to be the bloodiest ever.

Lenin was born into a well-to-do family in Simbirsk. His parents named him Vladimir Ilych Ulyanov. Later, following the practice of Russian revolutionaries, he took Lenin as his pseudonym. His grandfather on his mother’s side, Dr. Alexander Blank, was Jewish, about which a great deal was made later on, but Lenin had no memory of him at all, and there was no connection with Judaism in his life. Lenin’s father was a higher civil servant, and the family lived in the style of provincial dignitaries. His father died from a sudden illness in early 1886.

Lenin’s older brother Alexander was at university in St. Petersburg at the time. He was involved with one of the many revolutionary groups and identified with Russia’s intelligentsia, who were raised on Western education and saw their own society as culturally and politically backward.

For decades the intelligentsia had striven to bring Russia up to Western standards. Each generation experimented with different revolutionary tactics. Sometimes the mood gave rise to nihilists who rejected everything, and at other times revolutionaries were inspired by the idea of going to the people to “instruct” them.[8]

The intelligentsia from the 1870s onward grew more radical. On March 1, 1881, one of many splinter groups assassinated Tsar Alexan-der II, in hopes of stirring up massive social and political unrest and sparking revolution. Lenin’s brother joined another group intent on killing the successor to the throne, Alexander III. However, the ever- vigilant Okhrana, the secret police, got wind of the conspiracy. The plan had been to attack the tsar on March 1, 1887, the anniversary of the last tsar’s death. Arrests followed, and, shockingly for his family, Lenin’s older brother was hanged along with four others in May.

The young Lenin reacted quietly to these dramatic events. He had always been diligent in school, and he went back to his books and continued his studies. He registered as a student in the law faculty at Kazan University in the fall of 1887.

Little is known about Lenin’s extracurricular activities in this period, but as one might expect, he had some contact with student radicals and probably participated in protests against the government. As the brother of the conspirator and would-be assassin Alexander, he likely came under particular scrutiny from the tsarist authorities. While he was certainly not the student radical that subsequent Soviet lore made him out to be, he was duly rounded up by the police for the part he allegedly played in demonstrations. He was expelled from the university in December 1887 and exiled to Kokushkino, but by mid-1890 he was allowed to begin the process of registering as an external student at St. Petersburg University, from which he was awarded a law degree in November 1891. In the meantime, he had become a voracious reader of left-wing literature.

Lenin gravitated toward the fledgling Russian Marxist movement rather than the Russian populists, who emphasized agrarian Socialism. According to Karl Marx, the Socialist revolution was to be expected in the most advanced countries when the contradictions of mature capitalism reached a crisis that could not be resolved within the prevailing economic conditions. Even for committed Russian Marxists, it was certainly debatable whether Marx’s theories really fitted Russia, but Lenin took a doctrinaire approach and tried to “prove” that capitalism already existed there. He did not waver from this position and later, in 1899, published a large tome on the topic. Although it was filled with statistics and analysis of the driest kind, it surprisingly got the attention of young radicals in distant parts of the Russian Empire. Anastas I. Mikoyan, slightly younger (born 1895) than Lenin, but later t...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherKnopf

- Publication date2007

- ISBN 10 1400040051

- ISBN 13 9781400040056

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages720

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1400040051

Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # newMercantile_1400040051

Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard1400040051

Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover1400040051

Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1400040051

Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe

Book Description hardcover. Condition: New. New. Clean, unmarked pages. Fine binding and cover. Hardcover. Seller Inventory # 2308030009

Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon1400040051

LENIN, STALIN, AND HITLER: THE A

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 2.1. Seller Inventory # Q-1400040051