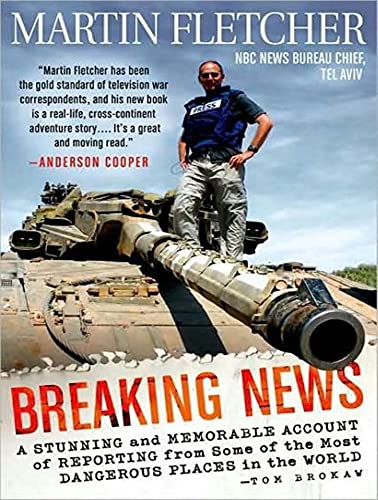

Breaking News: A Stunning and Memorable Account of Reporting from Some of the Most Dangerous Places in the World

These extraordinary, real-life adventure stories each examine different dilemmas facing a foreign correspondent. Can you eat the food of a warlord who stole it from the starving? Do you listen politely to a terrorist threatening to blow up your children? Do you ask the tough questions of a Khmer Rouge killer, knowing he is your only ticket out of the Cambodian jungle? And, above all, how do you stay sane when you're faced with so much pain?

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

The phone rang at noon and the message was brief: “Is that NBC? Tell Martin to come to a wedding. Tell him to come now. He can be a witness. Good-bye.”

I didn’t rush out to buy a present. This was no invitation to join a happy couple in holy matrimony. This “wedding” was more like a funeral. The message was code to witness a murder. The al-Aksa Martyrs’ Brigades in Nablus were going to kill a collaborator, and they wanted me and my NBC News team to film it.

Later I would get the details, and what a murky tale it was. The Israeli secret service had blackmailed a Palestinian man into becoming an informer. They knew he was having an affair with a married woman. The woman was married to a fighter with the al-Aksa brigades, who was hiding out in the Balata refugee camp with one of the top al-Aksa commanders. The Israelis wanted to kill them both.

The woman wanted to marry her lover, so she betrayed the hiding place of her husband and the militant leader. Israeli commandos stormed the safe house and found them crammed behind a false wall in a small room. In a hail of gunfire, the militants were killed. Case closed.

But al-Aksa knew there must have been a collaborator, and they quickly found him. And her. They videotaped their confessions against a plain white wall. The “wedding” was payback time.

When I got the call, I was shaken. How many dead people did I need to see? And I was confused. I understood al-Aksa’s rationale: “The collaborators must be killed or they’ll betray more people, and next time we’ll be killed. It’s them or us.”

But I also understood the collaborators: “We have no life under the Israelis. Our lives are ruined whatever we do.”

And I understood the Israelis: “Anything goes to stop the suicide bombers from killing more Jewish children. We’re fighting a war.”

As I put the phone down, I thought, I understand too much. I feel sorry for them all. But it occurred to me: If I sympathize with killers, informers, and blackmailers, maybe there’s something wrong with me, too.

It wouldn’t be surprising. After three decades covering war and suffering in every dark corner of the globe, anyone’s brain would be fried.

So what should I do? Film the killing or not? I sat down and stared at the phone, wondering whether to summon the team and hit the road. Ethically, it was a no-brainer. No way am I going to witness a murder. But hey, I thought, it’s going to happen anyway, if I’m there or not. It’s not my fault. And this is my job.

Nobody owns the moral high ground: My role in life is to see and report, and maybe learn a little. So there I sat, looking at the phone, and needing to decide quickly—should we go film the murder? This book is not a meditation on society, or a rant about how bad TV journalism has become, or a tell-all account of famous people I’ve met. It’s something simpler and, I hope, more revealing: a series of true-life adventure stories that expose the haunting dilemmas journalists face as we help write that famous first draft of history.

Year after year, my work takes me to the world’s most beautiful places at the worst of times. I visit with people at their lowest moments and tell their stories as best I can, while trying to cast light on the larger issues. At a time when the problems of strangers seem a world away, I try to answer the question: Why should we care? Sometimes the pictures tell the story, sometimes a word or two artfully mixed with a surprising juxtaposition does the job. Usually you can’t do better than let a person reveal himself. But however I do it, my job is to help people care about other people.

Unfortunately, that isn’t as morally clear-cut as it sounds. My work has led me again and again into pretty dicey territory. For instance, how callous can one be as a journalist seeking a story? I face that conundrum every day, and haven’t always handled it with flying colors.

When Turkey invaded Cyprus in 1974, my soundman trod on a land mine just three feet from me and was killed in the explosion. Moments later, another of my good friends trod on another land mine and vanished in flame and smoke. When I overcame my astonishment that I was still alive, I realized I had filmed it all. I hadn’t helped.

In a refugee camp in Wad Kowlie, on the Sudan border, I saw a man holding his starving infant. I happened to look into his eyes at the very moment he glanced down and realized that his child had just died in his arms. The man looked up, and our eyes met. Tears sprang to his eyes, as they did to mine. After all, at that time I had a child the same age as his. But I didn’t move forward to comfort him or even make a consoling gesture. As the man began to wail and stumbled away with his dead infant, I instinctively rushed off to find my cameraman and told him to follow the guy until he buried the kid. Great sequence.

In Cyprus, I was filming people in a deep ditch digging out a mass grave. Parts of stiff bodies stuck out of the packed mud in grotesque poses, like one of those artworks where a head and chest emerge from a wall. Everything was gray and dark and monotone, and my only response as they uncovered a woman’s body was to think, Oh good, she’s got a red dress on, some color for the picture.

Getting a good story while maintaining one’s humanity is difficult, yet it is hardly the only ethical challenge I’ve faced. For instance, how polite should I be when interviewing someone responsible for killing up to 2 million Cambodians? Is it wrong to stay in the home of a brutal Somali warlord, eating lavish food prepared by his Italian-trained chef, in order to report on, among other things, his theft of the same food from international aid organizations? And, critically for a young man with a growing family, how can one witness every imaginable horror and not take it out on the wife and kids?

This book does not offer solutions to these dilemmas, because there aren’t any; all you can do is feel your way as best you can. And yet, if I continue to cover wars after all these years, it is because I believe that, all things considered, I’ve done more good than harm. Given the great challenges facing humanity today, as well as all the mindless distractions that impede us, it’s critical to remind ourselves of what’s really important—human beings and the dire struggles for survival so many face every day. And that’s what war correspondents do.

The adventures in this book will, I hope, offer hours of entertaining reading. Yet I will have failed if in the very process of capturing readers’ imaginations I have not also left them with a keener and more visceral sense of the world’s pain. I will have failed if readers do not feel a new gratitude for the blessings they already enjoy, a sense that, as bad as life may be, it could always be a lot worse. That, in the end, is what I take away from all these years of murder and mayhem, which made me a connoisseur of sorrow. I dedicate Breaking News to my father, a reader, who knew great sorrow. He would suck mints, stroke his Snoopy doll, and doze off among piles of open books. He would dip in and out of volumes on comparative religion, European history, modern psychology, Talmudic thought, fiction by Oscar Wilde and Goethe, and plays by Molière and Aristophanes, reading all in their original languages, including Greek. He wasn’t a great listener, though, and he wasn’t much troubled by the kinds of professional dilemmas I face. Whenever he asked me about the war in Kosovo or revolution in Iran or wherever I had just returned from, he would quickly interrupt and correct me, based on his vast knowledge of history, the editorials of the right-wing English press, and the philosophy of Attila the Hun. His solution to most conflicts was the same: Line up five hundred men, shoot them, end of problem. His idea of a compromise was: Okay, three hundred. When I tried to respond, he would nod for a minute, then in midsentence remove his hearing aid and pick up a book. Interview over.

Unfortunately, my father didn’t live long enough to know about this book, let alone to spill coffee on it. Within two short years, my brother, Peter, died of leukemia; next my mother died following an operation; and then, about a year later, my father willed himself to death at the age of ninety. All this took place during the years 2000 through 2002, at the height of the second Intifada. Between suicide bombs and carnage in Israel, I flew to London, helping my dwindling family through sicknesses, intensive care, and funerals. Between reports for NBC, I wrote eulogies for my family members. My bosses were sympathetic, offering me all the free time I needed, for which I am grateful. But I was so swept along by the drama around me, at work and at home, that I had no time to mourn or reflect.

My father, a young lawyer, fled Vienna after escaping from a Nazi jail in 1938. Nine years later, two months after I was born in London, he changed his name to George Fletcher from Georg Fleischer, so that I wouldn’t get saddled with his English nickname: Flyshit. When he discovered that Fletcher was an ancient Scottish name meaning arrow maker, and that it was linked to the MacGregor clan, he bought a tartan tie and wore it to work at the button factory. He tried to blend in with the British but couldn’t. He never overcame the loss of his large extended family in the Holocaust; only he, a sister, and a niece survived. Nor did my mother, who along with her sister was her family’s sole survivor. After sixty years living in London, all their friends were from Central Europe. They were still refugees at heart, and they passed some of it on.

When I was mocked in first grade for calling corn on the cob “kookaroots,” the Hungarian word we used at home, I told my tormentor to “hupfingatsch,” Viennese dialect for “take a flying jump.” I squirmed in embarrassment when my parents spoke in their thick Viennese accents to my English schoolteachers. I always felt something of an outsider, even as I progressed through school, captained the soccer team, and worked at the BBC. It wasn’t England’s fault. England had sheltered Jewish refugees in their direst moment. But the burden of the Holocaust was too great for my parents, and they unloaded some of it onto me: a certain buried sadness, hatred for bullies, and sympathy for their victims.

But “one man in his time plays many parts,”* and it is only looking back that I see the connection between this inheritance and my career. I left the University of Bradford with a degree in modern languages and the offer of a job as a translator-interpreter in the Brussels headquarters of the European Community. It was the top of the translators’ ladder and paid a high salary, almost tax-free. It also offered all the perks befitting an international civil servant. I could have had a cushy life, but instead I chose to roam the world, look for faults everywhere I went, speak rudely to people in authority, and evade responsibility at every turn. In short, I became a journalist. It took me a long time to understand why the glove fit so well.

I am proud to say that I have rarely interviewed a head of state or a chief executive officer. I don’t care what the generals have to say. And don’t get me started on the royal family. Nobody with a story to sell or a policy to spin interests me. What I care about are the people who pay the price, as my family did.

On the day that I write this, I spent an hour with a man and woman whose ten-year-old daughter was killed. They showed me her school dress, ripped and red with blood, which they keep wrapped in a shopping bag in their neighbor’s apartment, because they can’t bear to keep it at home. It isn’t clear who killed their daughter, or why, but they want justice.

I’m not a cop, I can’t find out the answers, but I can help them ask the questions, and let them know that the world cares.

Copyright © 2008 by Martin Fletcher. All rights reserved.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherTantor Audio

- Publication date2008

- ISBN 10 1400107237

- ISBN 13 9781400107230

- BindingAudio CD

- Rating

Shipping:

US$ 4.97

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Breaking News: A Stunning and Memorable Account of Reporting from Some of the Most Dangerous Places in the World

Book Description AUDIO CD. Condition: Good. 8 AUDIO CDs, polished for your satisfaction for a worthwhile set, in the sturdy, clamshell case withdrawn from the library collection. Some library marking and sticker to the box and the CDs. Each audio CD is in an individual slot, protected and clear sounding. Enjoy this AUDIO CD performance!. Seller Inventory # Sand11520120179

Breaking News: A Stunning and Memorable Account of Reporting from Some of the Most Dangerous Places in the World

Book Description Condition: Good. SHIPS FROM USA. Used books have different signs of use and do not include supplemental materials such as CDs, Dvds, Access Codes, charts or any other extra material. All used books might have various degrees of writing, highliting and wear and tear and possibly be an ex-library with the usual stickers and stamps. Dust Jackets are not guaranteed and when still present, they will have various degrees of tear and damage. All images are Stock Photos, not of the actual item. book. Seller Inventory # 32-1400107237-G