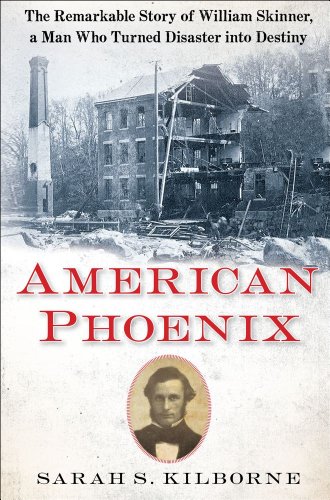

American Phoenix: The Remarkable Story of William Skinner, A Man Who Turned Disaster Into Destiny - Hardcover

The incredible story of nineteenth-century millionaire William Skinner, a leading founder of the American silk industry, who lost everything in a devastating flood—and his improbable, inspiring comeback to the pinnacle of the business world

In 1845 a young, penniless William Skinner sailed in steerage class on a boat that took him from the slums of London to the United States. Endowed with rare knowledge in the art of dyeing and an uncanny business sense, he acquired work in a fledgling silk mill in Massachusetts, quickly rising to prominence in the nation’s new luxury industry. Soon he opened his own factory and began turning out one of the bestselling silk brands in the country. Skinner was lauded as a pioneer in the textile industry and a manufacturer who knew no such word as fail. His business grew to sustain a bustling community filled with men, women, and children, living and working in the mill village of “Skinner-ville,” producing the country’s most glamorous, fashionable thread.

Then, in 1874, disaster struck. Hundreds of millions of gallons of water burst through a nearby dam, destroying everything in its path, including Skinnerville. Within fifteen minutes, Skinner’s entire life’s work was swept away, and he found himself one of the central figures in the worst industrial disaster the nation had yet known.

In this gripping narrative history, Skinner’s great-great-granddaughter, Sarah S. Kilborne, tells an inspiring, unforgettable American story—of a town devastated by unimaginable catastrophe; an industry that had no reason to succeed except for the perseverance of a few intrepid entrepreneurs; and a man who had nothing—and everything—to lose as he struggled to rebuild his life a second time.

None of Skinner’s peers who lost their factories in the Mill River Flood withstood the shock of their losses, but Skinner went on to stage one of the greatest comebacks in the annals of American industry. As a result of his efforts to survive, he became one of the leading silk manufacturers in the world, leaving an indelible imprint on the history of American fashion and style. More striking still, this achievement would never have been possible if Skinner hadn’t been ruined by the flood and forced, at age forty-nine, to start all over again, rebuilding everything with just one asset: the knowledge in his head.

With masterful skill Kilborne brings to life an era when fabric was fashion, silk was supreme, factories were beacons of American success, and immigrants like Skinner with the secrets of age-old European arts possessed knowledge worth gold to Americans. Here is a story of ambition and desire, resilience and faith, disaster and survival. It is about making it, losing it, and then making it again despite the odds. An enthralling tale, American Phoenix offers a new twist on the American dream, reminding us that just when we thought the dream was over, it may have only just begun.

***

FROM AMERICAN PHOENIX

As the train slowed in its approach to the depot at the northern end of Skinnerville, one of Skinner’s employees, John Ellsworth perhaps, awaited him on the platform. The depot was about a quarter mile from the house along a dark, unlit road. Thus when Skinner stepped down from the car and into the cold night air, he would have found both driver and horse all ready for the short jog home. The trip and this day were almost over, the anniversaries behind him, and a new year in the life of his marriage, his family, and his work was about to begin on the morrow. He was forty-nine years old, and the fabric of his existence had never been stronger. As he walked up the steps to his front door, there in the middle of Skinnerville, with the river flowing reliably behind him, the mill at rest across the way, the houses of his neighbors and employees all around, and a reunion with his wife and children just seconds ahead, there wasn’t one clue, nor any sign, that the very next morning nearly everything in his world would be swept away.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

The rain began before daybreak, not much at first, but enough to render it a damp and cheerless morning by the time the first bell rang at the mill, at half past five. This bell served as the workers’ alarm clock, alerting everyone at the boardinghouses that it was time to rise. Ellen Littlefield, who had boarded in Skinnerville for nearly seven years, was well used to the routine. A “packer” at Skinner’s mill, she worked on the ground floor of the office building in a room filled with drawers of finished silk and stacks of boxes for shipping. Of the five or so packers employed at this time, Ellen was arguably the most experienced, given her longevity in Skinner’s employ, and easily claimed respect as an old hand.

She was also, truth be told, fairly old to be working in the mill, having just celebrated her thirty-second birthday on May 8. Chances are, she marked the occasion with her closest friend at the mill, Aurelia Damon, who worked upstairs in the finishing room. At thirty-six Aurelia was Skinner’s oldest female employee and his only female employee to own a home. By 1872, after more than twelve years of working at the mill, Aurelia had earned enough money to build a “very pretty cottage” on the opposite side of the river. Ellen was a frequent visitor at this house, where she and Aurelia could feel comparatively youthful in the company of Aurelia’s infirm mother.

Most of the women that Skinner employed were in their late teens or early twenties. Many had come “seeking employment before marriage,” drawn to the independence that millwork afforded as well as the opportunity to put some money in their calico pockets (for dowries, clothing, and even, on occasion, education). Only a handful worked at the mill for more than a few years; rarely did any linger past thirty, a dangerous age for a woman still to be single. But Ellen doesn’t seem to have worried much about this, enjoying harmless flirtations with the likes of Tom Forsyth, that funny, handsome Englishman who worked in the winding room in the main part of the mill, or Nash Hubbard, “the widower,” who was hired within the past year as Skinner’s new bookkeeper.

As rain splattered on the windowsill, Ellen roused herself from the warmth of her bed, throwing off her heavy comforter and placing her bare feet on her large handmade rug. At this point in her career she’d graduated to having her own room—a rarity in boardinghouse life—and decorated it to her taste. Arranged here and there were books, magazines, and newspapers (she had a number of subscriptions), as well as her collection of photographs. Her melodeon, which she had been playing for about five years now, rested somewhere nearby, perhaps against the chair in which she practiced. And in one corner was a black walnut table made especially for custom sewing, of which Ellen did a great deal. Paper, ink, and letters lay about the room, awaiting Sunday, her day for correspondence. And curtains (made by her) hung in the windows, filtering the light on this cold, gray morning.

Gone were the days of sharing a bed with another boarder, in a room sleeping four or more. That was now the fate of the younger girls, most of whom boarded in the main house next door. The silk mill’s two boardinghouses, which looked like regular old farmhouses, were managed by a well-known local, Fred Hillman, and filled with about two dozen operatives at this time. That number was going to swell once Mr. Skinner began hiring again. No one knew just when that would be, of course, as Mr. S. had put off his plans temporarily “on account of the dull state of the market.” Even so, like the height of the river itself, such arrangements could change at any moment.

The Mill River was a modest waterway that originated in the mountains to the north and meandered rather pleasantly through Skinnerville. Unlike the mighty Connecticut, which flowed through three states, or the Merrimack, stretching from New Hampshire to Massachusetts, the Mill River was all of three towns long and forty feet wide. Still it made locals proud. “Seldom is there a river like our little Mill river,” the Northampton Free Press had written just a few days earlier, “that has the power to propel so many water-wheels that drive so much silk, cotton and woolen machinery, so many saws and lathes for iron, brass, wood and ivory buttons, flour and corn mills, and also saw mills and other things.” Indeed no fewer than sixty-four mills lined the river along its fourteen-mile run from the town of Williamsburg down through the town of Northampton.

Skinnerville, located within the township of Williamsburg, had been established in one of the river’s more advantageous bends. Although the northern reaches of the valley were rugged, rocky, and hilly, the land opened up at this point into a lovely little plain. Nearly all the houses in the village, most of them built within the past fifteen years, were alongside the road and the river. It was a pretty road, shaded by elms, sycamores, and maples, and in back of most of the houses were gardens and fields divided by stone walls. Because it was so close to the river, though, the village flooded easily, particularly in the spring when freshets, or flash floods, most commonly occurred.

In February 1873 Ellen had received a letter from one of her sisters, asking, “Have you any fear that there may be a freshet there this spring? Mother said yesterday that the water would be apt to be high through those valies [sic] if it kept on raining.” When springtime rains poured down, melting winter’s snow and ice, the volume of the area’s rivers naturally increased. Mill River became a considerable force, swollen and powerful, which was good for business since all that waterpower meant uninterrupted production at the valley’s factories. But the river’s swell could also rage out of control, back up behind ice jams, take out the wooden milldams, and otherwise cause a great deal of damage. To help ward against freshets and store some of that waterpower for later in the year, the manufacturers in Mill River Valley had built no fewer than four reservoirs, three up the west branch of the river and one up the east branch. These reservoirs were instrumental in controlling and regulating the area’s natural watershed.

The reservoir on the east branch had never gained the trust of many townsfolk. Known as the Williamsburg Reservoir, it covered over a hundred acres, was a mile long, and contained about 600 million gallons of water. Almost from the start its dam had leaked, but supporters pointed out that the dam had been made with tamped earth and the rivulets of water flowing through it were entirely characteristic of earthen dams. A co-owner of all four reservoirs, Skinner drew on this one as a source of humor. Someone had asked him a few months back, “What do you have for excitement up here nowadays?” “Well,” Skinner replied, “we occasionally have a freshet, then there is a general alarm that the reservoir has broken loose.”

At ten minutes to six the second bell pealed through the early-morning air, just twenty minutes after the first. Ready or not, breakfast was being served in the dining halls, and the Hillmans’ twenty or so boarders, Ellen included, rushed for the stairs, fussing with their clothes and greeting one another with groggy hellos. Then just half an hour later, the third morning bell rang. It was 6:20, ten minutes before anyone who worked in the silk mill, whether living in the boardinghouses or elsewhere, was to be at his or her respective post. Pushing back from the table, Ellen darted upstairs with the rest, donned her cloak and hat, and grabbed her umbrella and rubbers for good measure. In bad weather almost everyone wore rubbers over their everyday boots. Ellen had never seen any others like hers; they were “wired so the backs stood up about the ankle and one could just step into them.” Though perhaps not the most comfortable, they were easy to slip on in a rush before heading outdoors.

The road through Skinnerville, sleepy just minutes before, was suddenly alive with men, women, and children hurrying through the rain and coming in from all directions but heading toward the same: Skinner’s silk mill. The Cahill twins were coming down from the north, the Bartlett siblings from the south, the McGrath girls from the east. Close to sixty adult workers reported for work this morning, some forty women and twenty men, in addition to at least a dozen children and adolescents. Children were an integral part of the factory system in nineteenth-century America, composing their own class of workers within most industrial communities. Manufacturers benefited from their cheap labor, and families benefited from the extra income. The most progressive state in the union regarding child labor, Massachusetts had only two statutes for children under the age of fifteen: they couldn’t work more than ten-hour days, and they had to receive three months of schooling a year. A decade earlier Skinner had pushed for the town to build him a school; it was, conveniently, two doors down from the mill.

In silk mills, however, unlike cotton mills, children weren’t employed simply to run errands back and forth between departments or to replace full bobbins with empty ones on the spinning frames. Children stood before their own machines, finessing raw silk thread through tiny glass eyes and helping the brittle strands wind evenly, back and forth, on spool after spool. This was the very first stage in production at a silk mill, and it was generally considered ideal work for children, given their keen eyesight and nimble fingers. When discussing how John Ryle, mayor of Paterson, New Jersey, and one of the most eminent silk manufacturers in the country, began work at age five in a silk mill in England—an age too young even for most Americans—the trade journal Manufacturer and Builder was quick to explain, “The first process of silk manufacture is so light and delicate that it is adapted to the employment of very young children.”

Several local families were represented among Skinner’s operatives, with sisters and brothers growing up alongside one another in the mill. Henry Bartlett, for instance, who at twenty-five was a superintendent, had been in Skinner’s employ since he was six. He followed in the footsteps of two older sisters and one older brother and in turn led the way for two more siblings. Of the twelve living Bartlett children, half had worked at Skinner’s mill for a stretch of time, and four of them were still on the payroll.

Siblings were no less common among the boarders. Amid the throng of young women filing out of the boardinghouses this morning and emptying into the puddled street were five sets of sisters. In fact most of the boarders, Ellen included, had found work at the mill through a sibling. When Ellen arrived in Skinnerville for the first time, back in October 1867, two of her sisters were there to greet her, one older (Frances) and one younger (Lovisa). Neither was there any longer, each having moved on to another chapter in her life, but both Frances and Lovisa still had many friends in Skinnerville. Tom Forsyth had even named a dahlia after Frances, and Fred Hillman had made a special trip out of state to attend Lovisa’s wedding. A feeling akin to family grew among many who worked in the mill, so closely did they live and work together.

Though many of the boarders were from nearby towns, a few, like the Littlefields, who were from upstate New York, had come from places much farther away. The Kendall sisters were from Bethel, Vermont, almost 130 miles to the north. At a time when the fastest mode of transportation was a train traveling thirty-five miles per hour and most people traveled by horse and buggy (at an average of seven miles per hour), 130 miles was a tremendous distance to cover. Exactly what inspired the Kendalls to make the long trek to Skinnerville is hard to say, when there were certainly mill villages closer to home. But opportunity, in some form or another, brought them to Skinner’s door.

· · ·

Over at the mill Nash Hubbard stationed himself at a desk inside the main entrance and greeted each person who came in, noting his or her attendance. Umbrellas and raincoats dripped past him on the wooden floor as adults and children made wet trails toward their various departments. The foremen had already turned on the lamps, started up the machines, and begun feeding the furnace in the boiler house. Smoke was beginning to billow from the chimney, the turbine was beginning to churn in the wheelhouse, and the factory’s countless belts, pulleys, and shafts were beginning to whip and spin into action. In a matter of minutes everyone was seated or standing at a station, and by the time the clock struck 6:30 a.m. Skinner’s silk mill had started up for another day.

Those in the sorting room began picking through golden yellow raw silk from China, unfastening the large bales in which it had been shipped, removing the bundles of skeins, and then sorting the silk according to its fineness. Others were taking silk that had been sorted the day before, divvying it up into cotton bags, and lowering the bags into great boilers, softening the gummy silk to prepare it for winding. Over in their department the winders began winding the softened silk onto spools, while some of their neighbors were taking the spools just finished, fastening them onto cleaning machines, and running the silk through metal teeth to strip away any unevenness. From here the silk passed to the doublers, the spinners, and the twisters, who, on large spindled machines, doubled up strands of silk, spun them several times per inch, and twisted them tightly, sometimes in reverse, to create the strong, tensile thread that would bind men’s suits and ladies’ shoes. Then, finishing up this stage of the production, the reelers were prepping the thread for the dyehouse, taking it off the machine-specific spools and winding it back into skeins, or loose coils of silk.

Tom Skinner, chief dyer for his older brother, was starting his day as he would any other: washing out the tubs in the dyehouse to clean the pipes of any dirt that might have settled in them overnight. Dirt, after all, could ruin an entire batch of silk in the dyeing process, leaving it spotted and spoiled. At the other end of the mill complex, in the office building, the skeiners were beginning their day by taking some already dyed skeins, dividing them up according to custom orders, and arranging them into neat and orderly bundles. Traditionally all silk thread had been sold in skeins, but a manufacturer named Heminway in Connecticut had advanced the idea some time back of selling silk on wooden spools. This likely came about after the invention of the sewing machine, and spooled silk was now in great demand. Consequently, in a separate room, Skinner’s spoolers were reaching for hanks of dyed silk and transferring them back onto spools. This was a job that took considerable care because these were the actual spools (presumably stamped with the Unquomonk label) that would go to market. Spoolers had one of the few mechanical jobs that didn’t require them to be standing at a large spindled machine. Instead they sat six to a table, their feet working the pedals of their tabletop machines, as they wound the lustrous colored thread in even rows, back and forth, around and around the wooden bobbins. Finally, Ellen and the girls in the packing room were taking all that finished silk—skeined and spooled—wrapping it in paper, and carefully preparing it for transport.

By 6:45 the mill was buzzing with activity. Skinner had recently purchased a large supply of raw silk—one of the largest orders he’d ever made—so no one was i...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherFree Press

- Publication date2012

- ISBN 10 1451671792

- ISBN 13 9781451671797

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages448

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

American Phoenix: The Remarkable Story of William Skinner, A Man Who Turned Disaster Into Destiny

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # newMercantile_1451671792

American Phoenix: The Remarkable Story of William Skinner, A Man Who Turned Disaster Into Destiny

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1451671792

American Phoenix: The Remarkable Story of William Skinner, A Man Who Turned Disaster Into Destiny

Book Description Condition: New. . Seller Inventory # 52GZZZ00A20I_ns

American Phoenix: The Remarkable Story of William Skinner, A Man Who Turned Disaster Into Destiny

Book Description Condition: New. . Seller Inventory # 5AUZZZ000ADP_ns

American Phoenix: The Remarkable Story of William Skinner, A Man Who Turned Disaster Into Destiny

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new1451671792

American Phoenix: The Remarkable Story of William Skinner, A Man Who Turned Disaster Into Destiny

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon1451671792

American Phoenix: The Remarkable Story of William Skinner, A Man Who Turned Disaster Into Destiny

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1451671792

American Phoenix: The Remarkable Story of William Skinner, A Man Who Turned Disaster Into Destiny

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard1451671792

American Phoenix: The Remarkable Story of William Skinner, A Man Who Turned Disaster Into Destiny

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover1451671792

American Phoenix: The Remarkable Story of William Skinner, A Man Who Turned Disaster Into Destiny

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # VIB1451671792