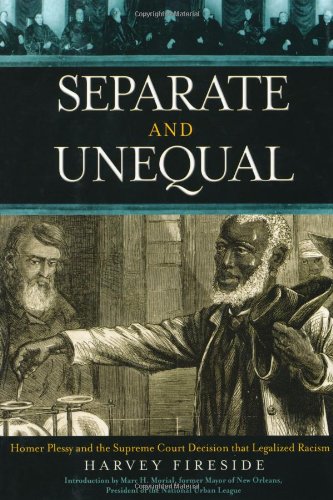

Separate and Unequal: Homer Plessy and the Supreme Court Decision that Legalized Racism - Hardcover

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

More than 100 years ago, in Plessy v. Ferguson, the United States Supreme Court found that a Louisiana law that required separate cars on trains for whites and "coloreds" was constitutional. Black people who believed that such segregated establishments were inferior suffered, in the Court's analysis, from low self-esteem.

Today the thousands of students who attend historically black colleges seem to agree. These African Americans have proudly chosen segregation over integration, at least for the purpose of higher education. The problem, however, is that in the interval the Supreme Court reversed course: Brown v. Board of Education, decided in 1954, declared that black schools were inherently unequal. Does that mean black colleges are unconstitutional? Are they at least politically incorrect? Given the history of white supremacy in the United States, is it possible that a black institution can ever be as good as a white one?

Two recent books, part of the cottage industry of publications commemorating (one hesitates to say "celebrating") the 50th anniversary of Brown, approach this issue from quite different directions. The titles imply the authors' points of view. Separate and Unequal is Harvey Fireside's critique of how Plessy, high on his list of "all-time most shameful" cases ever decided by the Court, "legalized racism." In Is Separate Unequal?, Albert Samuels makes the case for strong black institutions even in the post-civil-rights era.

Samuels, who graduated from historically black Southern University, where he now teaches political science, suggests that Brown reflects an "American Creed" that the law should not make racial distinctions. African-American political strategies, on the other hand, are informed by the black experience with slavery and discrimination and remain acutely race conscious.

While both books evaluate the morality of racial separation, Samuels's thesis is considerably more provocative. It's a shame that it's the less intriguingly written book.

Fireside, author of six previous books on civil rights issues, has written a riveting account of Plessy. Most of the facts have been noted by others, but they are no less fascinating in the re-telling. The central irony was that Homer Adolph Plessy looked white. Louisiana, however, followed the "one-drop" rule, which meant that a person with any African ancestry was considered black. Plessy was recruited by the Citizens Committee to Test the Constitutionality of the Separate Car Law. When on June 7, 1892, he boarded a "whites only" train car, the conductor had no idea that anything untoward was going on until Plessy said the sentence he had rehearsed: "I have to tell you that, according to Louisiana law, I am a colored man."

The railroad companies were on his side: After all, operating separate colored cars was expensive. Plessy was represented by Albion Tourgee, a white lawyer. Everyone expected that the law would be affirmed by the Louisiana courts, but there was hope that the U.S. Supreme Court would see things differently.

It did not. As the justices saw it, the law treated blacks and whites just the same -- both were subject to punishment for being in the wrong car. It seemed to the majority that Plessy's real complaint was that blacks were socially inferior to whites, which was not a problem that the law could solve.

Fireside is mildly critical of Tourgee's litigation skills, but considering that the vote was 7-1, one wonders whether any lawyer could have persuaded that court, which included former slave owners, to rule differently. The Supreme Court's blessing of American apartheid was, it turns out, the result of a test case gone terribly wrong.

Fireside is not a lawyer, and his long-winded analysis of the court's decision is less than insightful. For example, he accuses the majority of "simply disregarding the fourteenth amendment and its panoply of civil rights." The Court may have misinterpreted the amendment (although proponents of affirmative action would later agree that the Constitution does not require color-blindness) but it cannot fairly be said to have ignored it. Indeed, if the Court's reasoning was as superficial as Fireside makes it sound, it would not have taken nearly 50 years for Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP to get the decision overturned.

Fireside's treatment of Justice John Harlan's dissent is similarly unreflective. He cites with approval a passage in which Harlan states reassuringly that white race would be dominant "for all time" if whites followed Harlan's color-blind interpretation of the Constitution. And Fireside is silent about Harlan's appeal to a different racial prejudice to make his case: His dissent declared the Louisiana law illogical because it would permit a "Chinaman" to ride with white people, even though he was a member of a "race so different from our own that we do not permit those belonging to it to become citizens of the United States." Finally, Fireside does not sufficiently consider the possibility that the Louisiana Creoles who recruited Plessy to challenge the law -- a group descended from French settlers and African slaves -- resented the law's "one-drop" construction of race as opposed to its endorsement of segregation. In other respects, however, his analysis of the role of the mixed-race community is thoughtful and well-researched -- the book's most important contribution to our understanding of the case.

In practice the car designated for blacks was anything but equal. Black passengers were forced to share their compartment with anyone deemed unfit for the white car, including smokers, drunkards and convicts of any race. Whether African Americans would be exercised by segregation if their establishments were actually equal is the theme of Is Separate Unequal? The question must be presented hypothetically: The black colleges that Samuels uses to study the issue are largely inferior to their white counterparts in resources and reputation. Still they are a popular choice for African Americans, which makes Brown a difficult case for Samuels -- specifically, he argues that the Court's declaration that separate facilities are inherently unequal is a "troublesome assertion."

Samuels focuses on a 1992 Supreme Court case -- United States v. Fordice, in which the Court considered whether government support for black colleges is consistent with Brown. Samuels's conclusion is that the Court "erred badly" when it equated traditionally black colleges with "the regime of state-imposed, legal exclusion of blacks from all-white educational institutions." He is adept at exploring the tension that the case exposed among different groups of blacks, including the middle-class liberals who, in Fordice, supported the NAACP's goals of maximum integration and the students, especially Southerners, who seem to prosper in the educational environment at black schools.

A significant portion of the black community, he writes, viewed the NAACP as "out of step" with the best interests of African Americans. Indeed the success of historically black colleges raises "fundamental questions about the entire basis for the Court's decision in Brown." Samuels's book is a revision of his doctoral dissertation, and it reads like it. It is exhaustively researched, but much of the writing is dry. There are too many long descriptions of court cases. Samuels ignores the important affirmative action cases the Court decided last summer, which seems strange in light of the space devoted to their precedents. But these are minor complaints. Overall the book is a timely and provocative analysis of an under-theorized part of civil rights jurisprudence -- the preference of some African Americans to learn with their own kind.

Reviewed by Paul Butler

Copyright 2004, The Washington Post Co. All Rights Reserved.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherCarroll & Graf

- Publication date2003

- ISBN 10 0786712937

- ISBN 13 9780786712939

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages336

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.50

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Separate and Unequal: Homer Plessy and the Supreme Court Decision that Legalized Racism

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0786712937

Separate and Unequal: Homer Plessy and the Supreme Court Decision that Legalized Racism

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0786712937

Separate and Unequal: Homer Plessy and the Supreme Court Decision that Legalized Racism

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0786712937

SEPARATE AND UNEQUAL: HOMER PLES

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.52. Seller Inventory # Q-0786712937