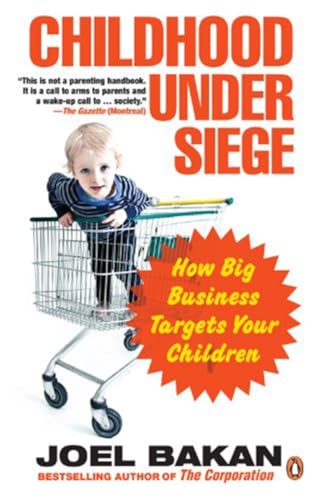

Childhood Under Siege: How Big Business Targets Your Children - Softcover

From the writer of the hit film and international bestselling book The Corporation comes a shocking venture behind the scenes of the widespread manipulation of children by profit-seeking corporations—and of society’s failure to protect them.

Childhood Under Seige reveals big business’s discovery of a new resource to be mined for profit—our children. A journey through a world of unabashed exploitation, clued-out parents, and governments that look the other way, it tells the chilling and at times darkly humorous story of business’s plans to turn kids into obsessive and narcissistic mini-consumers, media addicts, cheap and pliable workers, and chemical industry guinea pigs. Not to mention pharmaceutical pill poppers—psychotropic drug consumption by children has increased fivefold since 1980.

It’s a winner-takes-all battle for children’s hearts, minds and bodies as corporations pump billions into rendering parents and governments powerless to protect children from their calculated commercial assault and its disturbing toll on their health and well-being.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

JOEL BAKAN is an internationally recognized and award-winning scholar and teacher who has worked on landmark legal cases and government policies. His bestselling book The Corporation was made into an award-winning documentary. He lives in Vancouver.

Over the last 150 years the corporation has risen from relative obscurity to become the world's dominant economic institution. Today, corporations govern our lives. They determine what we eat, what we watch, what we wear, where we work, and what we do. We are inescapably surrounded by their culture, iconography, and ideology. And, like the church and the monarchy in other times, they posture as infallible and omnipotent, glorifying themselves in imposing buildings and elaborate displays. Increasingly, corporations dictate the decisions of their supposed overseers in government and control domains of society once firmly embedded within the public sphere. The corporation's dramatic rise to dominance is one of the remarkable events of modern history, not least because of the institution's inauspicious beginnings.

Long before Enron's scandalous collapse, the corporation, a fledgling institution, was engulfed in corruption and fraud. Throughout the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, stockbrokers, known as "jobbers," prowled the infamous coffee shops of London's Exchange Alley, a maze of lanes between Lombard Street, Cornhill, and Birchin Lane, in search of credulous investors to whom they could sell shares in bogus companies. Such companies flourished briefly, nourished by speculation, and then quickly collapsed. Ninety-three of them traded between 1690 and 1695. By 1698, only twenty were left. In 1696 the commissioners of trade for England reported that the corporate form had been "wholly perverted" by the sale of company stock "to ignorant men, drawn in by the reputation, falsely raised and artfully spread, concerning the thriving state of [the] stock." Though the commissioners were appalled, they likely were not surprised.

Businessmen and politicians had been suspicious of the corporation from the time it first emerged in the late sixteenth century. Unlike the prevailing partnership form, in which relatively small groups of men, bonded together by personal loyalties and mutual trust, pooled their resources to set up businesses they ran as well as owned, the corporation separated ownership from management -- one group of people, directors and managers, ran the firm, while another group, shareholders, owned it. That unique design was believed by many to be a recipe for corruption and scandal. Adam Smith warned in The Wealth of Nations that because managers could not be trusted to steward "other people's money," "negligence and profusion" would inevitably result when businesses organized as corporations. Indeed, by the time he wrote those words in 1776, the corporation had been banned in England for more than fifty years. In 1720, the English Parliament, fed up with the epidemic of corporate high jinks plaguing Exchange Alley, had outlawed the corporation (though with some exceptions). It was the notorious collapse of the South Sea Company that had prompted it to act.

Formed in 1710 to carry on exclusive trade, including trade in slaves, with the Spanish colonies of South America, the South Sea Company was a scam from the very start. Its directors, some of the leading lights of political society, knew little about South America, had only the scantiest connection to the continent (apparently, one of them had a cousin who lived in Buenos Aires), and must have known that the King of Spain would refuse to grant them the necessary rights to trade in his South American colonies. As one director conceded, "unless the Spaniards are to be divested of common sense...abandoning their own commerce, throwing away the only valuable stake they have left in the world, and, in short, bent on their own ruin," they would never part with the exclusive power to trade in their own colonies. Yet the directors of the South Sea Company promised potential investors "fabulous profits" and mountains of gold and silver in exchange for common British exports, such as Cheshire cheese, sealing wax, and pickles.

Investors flocked to buy the company's stock, which rose dramatically, by sixfold in one year, and then quickly plummeted as shareholders, realizing that the company was worthless, panicked and sold. In 1720 -- the year a major plague hit Europe, public anxiety about which "was heightened," according to one historian, "by a superstitious fear that it had been sent as a judgment on human materialism" -- the South Sea Company collapsed. Fortunes were lost, lives were ruined, one of the company's directors, John Blunt, was shot by an angry shareholder, mobs crowded Westminster, and the king hastened back to London from his country retreat to deal with the crisis. The directors of the South Sea Company were called before Parliament, where they were fined, and some of them jailed, for "notorious fraud and breach of trust." Though one parliamentarian demanded they be sewn up in sacks, along with snakes and monies, and then drowned, they were, for the most part, spared harsh punishment. As for the corporation itself, in 1720 Parliament passed the Bubble Act, which made it a criminal offense to create a company "presuming to be a corporate body," and to issue "transferable stocks without legal authority."

Today, in the wake of corporate scandals similar to and every bit as nefarious as the South Sea bubble, it is unthinkable that a government would ban the corporate form. Even modest reforms -- such as, for example, a law requiring companies to list employee stock options as expenses in their financial reports, which might avoid the kind of misleadingly rosy financial statements that have fueled recent scandals -- seem unlikely from a U.S. federal government that has failed to match its strong words at the time of the scandals with equally strong actions. Though the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, signed into law in 2002 to redress some of the more blatant problems of corporate governance and accounting, provides welcome remedies, at least on paper, the federal government's general response to corporate scandals has been sluggish and timid at best. What is revealed by comparing that response to the English Parliament's swift and draconian measures of 1720 is the fact that, over the last three hundred years, corporations have amassed such great power as to weaken government's ability to control them. A fledgling institution that could be banned with the stroke of a legislative pen in 1720, the corporation now dominates society and government.

How did it become so powerful?

The genius of the corporation as a business form, and the reason for its remarkable rise over the last three centuries, was -- and is -- its capacity to combine the capital, and thus the economic power, of unlimited numbers of people. Joint-stock companies emerged in the sixteenth century, by which time it was clear that partnerships, limited to drawing capital from the relatively few people who could practicably run a business together, were inadequate for financing the new, though still rare, large-scale enterprises of nascent industrialization. In 1564 the Company of the Mines Royal was created as a joint-stock company, financed by twenty-four shares sold for £1,200 each; in 1565, the Company of Mineral and Battery Works raised its capital by making calls on thirty-six shares it had previously issued. The New River Company was formed as a joint-stock company in 1606 to transport fresh water to London, as were a number of other utilities. Fifteen joint-stock companies were operating in England in 1688, though none with more than a few hundred members. Corporations began to proliferate during the final decade of the seventeenth century, and the total amount of investment in joint-stock companies doubled as the business form became a popular vehicle for financing colonial enterprises. The partnership still remained the dominant form for organizing businesses, however, though the corporation would steadily gain on it and then overtake it.

In 1712, Thomas Newcomen invented a steam-driven machine to pump water out of a coal mine and unwittingly started the industrial revolution. Over the next century, steam power fueled the development of large-scale industry in England and the United States, expanding the scope of operations in mines, textiles (and the associated trades of bleaching, calico printing, dyeing, and calendaring), mills, breweries, and distilleries. Corporations multiplied as these new larger-scale undertakings demanded significantly more capital investment than partnerships could raise. In postrevolutionary America, between 1781 and 1790, the number of corporations grew tenfold, from 33 to 328.

In England too, with the Bubble Act's repeal in 1825 and incorporation once again legally permitted, the number of corporations grew dramatically, and shady dealing and bubbles were once again rife in the business world. Joint-stock companies quickly became "the fashion of the age," as the novelist Sir Walter Scott observed at the time, and as such were fitting subjects for satire. Scott wryly pointed out that, as a shareholder in a corporation, an investor could make money by spending it (indeed, he likened the corporation to a machine that could fuel its operations with its own waste):

Such a person [an investor] buys his bread from his own Baking Company, his milk and cheese from his own Dairy Company...drinks an additional bottle of wine for the benefit of the General Wine Importation Company, of which he is himself a member. Every act, which would otherwise be one of mere extravagance, is, to such a person...reconciled to prudence. Even if the price of the article consumed be extravagant, and the quality indifferent, the person, who is in a manner his own customer, is only imposed upon for his own benefit. Nay, if the Joint-stock Company of Undertakers shall unite with the medical faculty...under the firm of Death and the Doctor, the shareholder might contrive to secure his heirs a handsome slice of his own death-bed and funeral expenses.

At the moment Scott was satirizing it, however, the corporation was poised to begin its ascent to dominance over the economy and society. And it would do so with the help of a new kind of steam-driven engine: the steam locomotive.

America's nineteenth-century railroad barons, men lionized by some and vilified by others, were the true creators of the modern corporate era. Because railways were mammoth undertakings requiring huge amounts of capital investment -- to lay track, manufacture rolling stock, and operate and maintain systems -- the industry quickly came to rely on the corporate form for financing its operations. In the United States, railway construction boomed during the 1850s and then exploded again after the Civil War, with more than one hundred thousand miles of track laid between 1865 and 1885. As the industry grew, so did the number of corporations. The same was true in England, where, between 1825 and 1849, the amount of capital raised by railways, mainly through joint-stock companies, increased from £200,000 to £230 million, more than one thousand-fold.

"One of the most important by-products of the introduction and extension of the railway system," observed M. C. Reed in Railways and the Growth of the Capital Market, was the part it played in "assisting the development of a national market for company securities." Railways, in both the United States and England, demanded more capital investment than could be provided by the relatively small coterie of wealthy men who invested in corporations at the start of the nineteenth century. By the middle of the century, with railway stocks flooding markets in both countries, middle-class people began, for the first time, to invest in corporate shares. As The Economist pronounced at the time, "everyone was in the stocks now...needy clerks, poor tradesman's apprentices, discarded service men and bankrupts -- all have entered the ranks of the great monied interest."

One barrier remained to broader public participation in stock markets, however: no matter how much, or how little, a person had invested in a company, he or she was personally liable, without limit, for the company's debts. Investors' homes, savings, and other personal assets would be exposed to claims by creditors if a company failed, meaning that a person risked financial ruin simply by owning shares in a company. Stockholding could not become a truly attractive option for the general public until that risk was removed, which it soon was. By the middle of the nineteenth century, business leaders and politicians broadly advocated changing the law to limit the liability of shareholders to the amounts they had invested in a company. If a person bought $100 worth of shares, they reasoned, he or she should be immune to liability for anything beyond that, regardless of what happened to the company. Supporters of "limited liability," as the concept came to be known, defended it as being necessary to attract middle-class investors into the stock market. "Limited liability would allow those of moderate means to take shares in investments with their richer neighbors," reported the Select Committee on Partnerships (England) in 1851, and that, in turn, would mean "their self-respect [would be] upheld, their intelligence encouraged and an additional motive given to preserve order and respect for the laws of property."

Ending class conflict by co-opting workers into the capitalist system, a goal the committee's latter comment subtly alludes to, was offered as a political justification for limited liability, alongside the economic one of expanding the pool of potential investors. An 1853 article in the Edinburgh Journal, stated:

The workman does not understand the position of the capitalist. The remedy is, to put him in the way by practical experience....Working-men, once enabled to act together as the owners of a joint capital, will soon find their whole view of the relations between capital and labour undergo a radical alteration. They will learn what anxiety and toil it costs even to hold a small concern together in tolerable order...the middle and operative classes would derive great material and social good by the exercise of the joint-stock principle.

Limited liability had its detractors, however. On both sides of the Atlantic, critics opposed it mainly on moral grounds. Because it allowed investors to escape unscathed from their companies' failures, the critics believed it would undermine personal moral responsibility, a value that had governed the commercial world for centuries. With limited liability in place, investors could be recklessly unconcerned about their companies' fortunes, as Mr. Goldbury, a fictitious company promoter, explained in song in Gilbert and Sullivan's sharp satire of the corporation, Utopia Ltd:

Though a Rothschild you may be, in your own capacity,

As a Company you've come to utter sorrow,

But the liquidators say, "Never mind -- you needn't pay,"

So you start another Company Tomorrow!

People worried that limited liability would, as one parliamentarian speaking against its introduction in Englan said, attack "The first and most natural principle of commercial legislation...that every man was bound to pay the debts he had contracted, so long as he was able to do so" and that it would "enable persons to embark in trade with a limited chance of loss, but with an unlimited chance of gain" and thus encourage "a system of vicious and improvident speculation."

Despite such objections, limited liability was entrenched in corporate law, in England in 1856 and in the United States over the latter half of the nineteenth century (though at different times in different states). With the risks of investment in stocks now removed, ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherPenguin Canada

- Publication date2012

- ISBN 10 0143170430

- ISBN 13 9780143170433

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages304

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Childhood Under Siege: How Big Business Targets Your Children

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.65. Seller Inventory # G0143170430I3N00

Childhood Under Siege: How Big Business Targets Your Children

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.65. Seller Inventory # G0143170430I3N00

Childhood Under Siege: How Big Business Targets Your Children

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.65. Seller Inventory # G0143170430I4N00

Childhood Under Siege: How Big Business Targets Your Children

Book Description Condition: Good. Buy with confidence! Book is in good condition with minor wear to the pages, binding, and minor marks within 0.7. Seller Inventory # bk0143170430xvz189zvxgdd