INTRODUCTION

THE FACE, THE FACTS AND THE PORN, OR WHY WE MUST STOP CONDESCENDING TO THE PAST

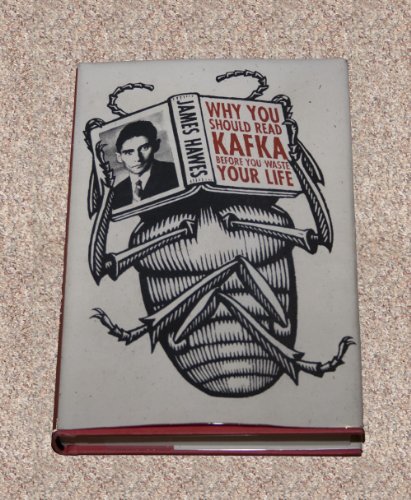

The Face of Kafka

You know the face I mean, of course. Everyone does. There are many photos of Dr. Franz Kafka (1883–1924) but, as far as Prague souvenirs and English-language biographies go, this might as well be the only one.

Now, this is very unusual for a writer. Who would bet on being able to finger Flaubert, Stendhal, Dostoyevsky, James, Conrad, and Proust in an identification parade of random upper-middle-class men of the past? And why should anyone care to? They are remembered for their books, not their looks. Dickens has a memorable hairstyle, true, and a couple of other modern author photos have become local tourist icons for the cities they fled (Dublin makes a fine old effort with James Joyce, and Swansea tries with Dylan Thomas), but Kafka is in a different international league. Apart from Shakespeare, there’s simply

no writer whose image is so well known to so many people who have never read a word he wrote. The face of Kafka has become virtually a brand.

Not that Kafka doesn’t deserve his fame. If ever mankind gets to the stars, people commuting between planets will know of his work. I spent ten years of my life studying that work, teaching it at universities, publishing articles on it in weighty journals—and I can’t think of many better ways to spend ten years.*

But Kafka’s fame is strange. Dante, Shakespeare, Goethe, Keats, Flaubert, Dickens, Chekhov, Proust, Joyce are all quoted. It’s their

words that count, which, since words were all they left behind them, seems pretty logical. Kafka’s words are probably quoted less often than those of any other writer of his rank: he is world famous for his

visions.

You can see why: A man wakes up and finds that he’s a beetle. A man who has done nothing wrong fights for his life against a bizarre court that sits in almost every attic in the world. A machine quite literally writes condemned people to death. A man tries forever to get into a mysterious castle. A man waits in vain all his life by the Door to the Law, only to be told as he dies that this door was only ever meant for him. These visions haunt the world like those of no other self-conscious, modern author. They have the cthonic power of mysterious fragments from a lost scroll of the Pentateuch or a tantalizingly half-preserved Greek myth.

Yet no image becomes immortal just because it’s a great High Concept. The dustbin of literary history is filled with the wrecks of ideas that looked great on the backs of envelopes. Every half-cultured Westerner has at least vaguely heard of Don Quixote and his windmills, but no one would know of this vision today if Cervantes had just sent it out as a witty one-liner. It lives only because it’s part of a larger whole that

worked for the people who first read it—and was therefore transmitted down to the next generation, who agreed, and so on.

*See (if you insist), J. M. Hawes,

Nietzsche and the End of Freedom, the neo-Romantic Dilemma in Kafka, the Brothers Mann, Rilke and Musil, Frankfurt (Lang) 1993; ‘Blind Resistance? A reply to Elizabeth Boa’s reading of Kafka’s

Auf der Galerie’ in Deutsche Vierteljahrsschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Geistesgeschichte, 69. Jahrgang, Heft 2/June 1995, pp.324–36; The Psychology of Power in Kafka’s

Der Process and Heinrich Mann’s

Der Untertan, in

Oxford German Studies 17/18 (1990), pp.119–31;

Faust and Nietzsche in Kafka’s

Der Process, in

New German Studies 15/2, 1989.

What counts, in other words, is not only the tale but also the telling. This is where the K.-myth comes in—or, rather, gets in the way. It continually pushes the idea of a mysterious genius, a lonely Middle European Nostradamus, who, almost ignored by his contemporaries, somehow plumbed the depths of his mysterious, quasi-saintly psyche to predict the Holocaust and the Gu-lags. The brooding face of Kafka has become the icon of that K.-myth and his name, typographically irresistible to anyone from west of the Rhine (

my dear, that mysterious Z, that oh-so-non-Western double K!) has entered the languages of the world in the term kafkaesque, used wherever guiltless people are trapped in some nightmarish bureaucratic catch-22.

In the very simplest of ways, we can see that it’s only a myth. That photo, overwhelmingly the most famous image of him, the international trademark of Prague (which Kafka longed for years to escape), was actually taken in a department store in Berlin (which he longed for years to get to). It’s also the last picture of him ever taken. This is loading the dice somewhat. What we now know as the face of Kafka was created about eight months before his death, when he knew logically that he was doomed (he compared his move to Berlin to Napoleon’s invasion of Russia) but had not quite given up on the irrational hope of still finding real, human life and love.

This state of mind is (a) typical of his writing and (b) liable to make anyone look profound.

But still not profound enough. The legendary Kafka collector and publisher Klaus Wagenbach recalls watching in the early fifties as the S. Fischer Co. artists retouched this picture to give Kafka’s eyes the desired gleam. And it worked.

Prophetic Kafka is now as famous and vague an icon as Saintly Che Guevara—and with about as much historical accuracy.

Faces are not just faces; they carry stories. Evolution has minutely tuned our attention to what they say. The whole modern visually driven circus of media stardom depends on our ancient hominid instincts to note and judge incredibly precise facial details. So even if you’ve never read a word of Kafka, you’ll feel— you won’t be able to help feeling—that, since you know his icon, you know something about him.

As far as I can tell, most English-speakers seem to pick up Kafka’s writings vaguely expecting something like a mixture of Edgar Allan Poe,

The Fly, Philip K. Dick, and 1984. No other writer’s work suffers from this kind of prejudgment. It means that readers come to Kafka already beholding the (alleged) man, forgetting that in the beginning were his words.

But there are biographies, guidebooks, and essay-writing aids aplenty, never mind the practically infinite mass of academic interpretation that has gathered around this physically modest corpus of work (never in the history of literary scholarship have so many written so much about so little). So surely, it’s easy to get to know more about Kafka before taking the supposedly heavy plunge into his actual works. Probably, you already know some of these "facts" yourself:

· Kafka’s will ordered that all his works should be destroyed.

· Kafka was virtually unknown in his lifetime, partly because he was shy about publishing.

· Kafka was terrified of his brutal father.

· Kafka was crushed by a dead-end bureaucratic job.

· Kafka was crippled for years by the TB that he knew must inevitably kill him.

· Kafka was incredibly honest about his failings with the women in his life—

too honest.

· Kafka was imprisoned, as a German-speaking Jew in Prague, in a double ghetto: a minority-within-a-minority amid an absurd and collapsing operetta-like empire.

· Kafka’s works are based on his experiences as a Jew.

· Kafka’s works uncannily predict Auschwitz.

· Kafka’s works were burned by the Nazis.

These are the building blocks of the K.-myth. Unfortunately, they are all rubbish—so much so that, at present, it’s drastic but true to say that the less you know about Kafka’s alleged life the greater chance you have of enjoying his superb writing.

This is just as true for most people who are formally taught about Kafka at school or college. What is taught at most institutions is just a version of the above rubbish. Two generations of adoring biographers and theorizing academics have churned out an image of perfect human profundity (which moves books) and unfathomable literary/psychological complexity (which sells research proposals). Do they care to represent the real Dr. Franz Kafka (1883–1924)? No, thank you. Really, they are in the same game as the sellers of tourist knickknacks in Prague. All they want is K., a face-and-name icon that will bring, through the doors of their shops or lecture halls, people who have never read his writings, a brand to hang their businesses and theories on.

In the last few years, the very best Kafka people have at last begun to argue against this comfortable rubbish. This book is indebted deeply to them.* However, it’s a tough job.

Scholarly discussions can all too easily (and often, quite rightly) be dismissed as mere insider pitches for grants, jobs, and research posts. If there’s one idea that resounds through Kafka’s writing, it’s that rational arguments, however objectively true they may be, simply bounce right off the stories we want to believe.

*See

Further Reading. The most important (as will be seen from the number of times I refer to it) is Peter-André Alt’s

Der ewige Sohn. It’s crazy that this mighty biography, which makes all others obsolete, is still unavailable in English.

In his own case, the K.-myth is so spectacularly fake you have to conclude that a lot of people really, really want that myth rather than the facts. And when you’re going after people’s beloved idols, the only way to philosophize is with a hammer or, to use Kafka’s image rather than Nietzsche’s, with an axe to break the frozen sea of Kafka studies.

So this book isn’t going to

argue that the K.-myth has wildly skewed our view of Kafka and his writings. It’s going to

show it— where necessary, by using some long-lost dynamite that no one, not even the best modern German scholars, has ever used before.

We’ll see how the K.-myth has so blinded scholars that, despite all the hundreds or thousands of PhDs awarded on Kafka, not one of them, not even the latest Germans, has ever noticed that Kafka’s most famous single image—

that beetle—is the cultural equivalent of James Joyce’s quoting the opening scene of

Hamlet at the start of

Ulysses.*

We’ll see Kafka himself, saying that he "simply imitated" Dickens and took his observational method from Sherlock Holmes. We’ll see him reducing his first listeners (as well as himself) to

helpless laughter as he reads the most famous opening of any twentieth-century novel. We’ll see him being pushed by a powerful literary clique. We’ll see him, a high-ranking Jew in the service of a militaristic, authoritarian German-speaking empire that ruled a Czech-speaking country, quite literally investing in victory over the Allies.

And we’ll see what two entire generations of scholars have

never shown to Kafka’s readers, the stuff that Kafka himself (quite understandably) kept hidden away in his locked bookcase and which his acolytes have made sure has stayed safely locked away ever since. Pictures that, when I first saw them, made me rub my eyes, then quickly take the files for this book off the family PC desktop and save them where my two preteen boys wouldn’t come across them. Kafka’s porn.

*I couldn’t believe this myself at first. So I checked with Professor Ritchie Robertson, Chair of German at Oxford University, Britain’s undisputed Kafka Champion.

The past won’t be condescended to. In 1907, a public glimpse of stocking was shocking, since respectable women such as Ms. Felice Bauer still dressed according to a code that would essentially pass muster with today’s Islamic vigilantes. So when Kafka’s contemporaries, Joyce and Conrad, give us comic scenes of sneaky porn-buying in

Ulysses and The Secret Agent, modern readers are apt to assume that these are cases of laughably harmless "naughty" stuff. But the images that Kafka himself ordered, paid for, and kept carefully hidden away would, even today, put the journals firmly on the top shelf. It may well be illegal for you to look at them if you’re under eighteen (or, indeed at all, in certain lands).

But that’s the whole point. Only if we stop condescending to the past will we ever see Kafka as he really was, allowing us to sidestep the K.-myth and read his works afresh, not just as mighty one-liners but as the splendid and often surprising works they really are. Works that did not spring from timeless subterranean depths but have a quite clear ancestry and place within the story of Western literature.

So let’s start with a look at one day in the life this man and his world—a world that was once just as real as ours, but which is now utterly, almost unimaginably lost. A look at the way things once really

were ...

Excerpted from Why You Should Read Kafka Before You Waste Your Life by James Hawes

Copyright © 2008 by James Hawes

Published in 2008 by St. Martin’s Press

All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the Publisher