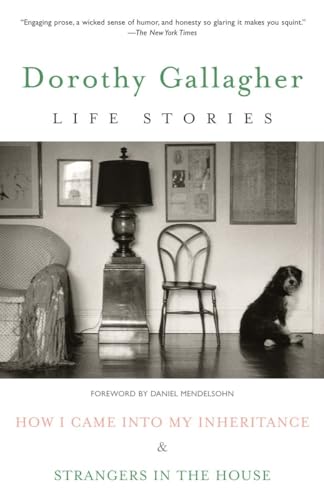

Life Stories: How I Came Into My Inheritance & Strangers in the House - Softcover

Here are two acclaimed memoirs in one remarkable volume. In an extraordinarily compelling voice, Dorothy Gallagher tells stories taking us from her parents’ beginnings in the Ukraine to her own childhood in 1940s New York, through the many adventures of her extended family and into her own adult life. Her themes are universal: the fragility of friendship, the power of love, the marital crisis brought on by chronic illness, the role of dumb luck at the heart of life–Gallagher dramatizes her stories with acute insight, strong feeling, and edgy wit.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Dorothy Gallagher is the author of How I Came Into My Inheritance and Other True Stories, a New York Times Notable Book, one of Time magazine’s best books of the year, and a runner-up for the PEN/Martha Albrand Award for the Art of the Memoir; Hannah’s Daughters: Six Generations of an American Family, 1876—1976; and All the Right Enemies: The Life and Murder of Carlo Tresca, a New York Times Notable Book. Her work has appeared in The New York Times Magazine, The New York Times Book Review, and Grand Street. She was born and raised and now lives in New York.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

Chapter 1

The Making of Me

I ran into Jack Hoffman on the street. I hadn’t seen him in ages.

We said “How are you?” and “What’s new?”

“Did you hear?” he said. “Victor’s dead. Heart attack. Five years ago.”

“Really?” I said.

“Yes,” he said. “Really.”

“Dr. Nielsen?” I said the first time I went to his office.

He nodded. He never argued with that form of address.

This was Victor Nielsen, not any sort of doctor; a former opera singer (Danish). Those were the days when anyone could hang out a shingle as a “lay” analyst.

You might expect a Dane to be tall and blond. Not so Victor. He was about fifty then, not in the least handsome, short and stocky, with a fleshy face. But he had a large head, thick gray hair, and he looked bigger sitting down. Sitting down was a major part of his job. Also he had very blue eyes; and his low, well-trained, charmingly accented voice, a beautiful voice, which gave him great authority; and in the end you had to say that, all in all, he was an attractive man.

His office was somewhere on the Upper West Side, Eighty-sixth Street, I think, just a few doors in from Broadway. It was a large room, bright, uncurtained, just above street level. Standing, you had a perfect view of the street life below; sitting, you saw the heads of people walking past the windows. I sat across the desk from Victor. (“Call me Victor,” he said, waving away any need for the spurious title.) I had expected a leather couch, but his office contained only the desk, a couple of chairs, a Marimekko sort of rug, and a daybed with a rough cotton throw, drab blue, as I remember. In due course, I thought, I would be invited to lie down.

Why was I there? Hindsight shows me that I was just ahead of the sea change. Only a few years later, a nineteen-year-old girl—confused, moody, depressed, reluctantly promiscuous—would be engulfed by a culture and a cause—drugs, casual sex, communes, Vietnam; would know what clothes to wear—

vintage dresses, army castoffs, jeans, T-shirts; would know how to do her hair—parted in the middle, flowing down her back; and would know what music belonged to her—Dylan, Baez, etc. As it was, I wore the hateful garter belts and stockings of my time, straight woolen skirts and shirtwaist dresses; set my hair every night to appear as a shoulder-length pageboy in the morning; listened to Frank Sinatra and Vaughn Monroe, who certainly weren’t bad but weren’t mine.

My mother was at her wits’ end. She consulted her cousin Sylvia, the social worker.

“I can’t deal with her,” my mother said. “She leaves school, she stays out all night, she won’t tell me where she goes, she moves out of the house, she moves back in, she can’t keep a job, she won’t talk to me.”

Sylvia, being a social worker, knew what to do. “Send her to an analyst,” she said. “I know someone.”

So now I was sitting across the desk from my analyst, and what did he say to me?

“I’m going to make a real little woman out of you.”

Once a week, over a couple of years, I saw Victor Nielsen. Apart from that promise, which he often repeated, I can’t remember another word of what passed between us. No doubt I talked about my mother, my father, and how they had ruined my life. At the time, I happened to be lovesick for a man who would marry me two years later; in the meantime, he had dumped me, and I was sleeping with almost anyone who asked. Each time I told Victor about one of these incidents, he said, “You have the makings of a real little woman.”

Who was right about this: Victor? Or my father, who had taken to calling me a prostitute?

Well of course I was not a prostitute, although I could see where he might get that idea. If he had known about it, for instance, my father could have said that I once did it for a dime. I was visiting San Francisco, and a guy whose name I no longer remember had kindly taken me to see the sights. We spent a long day together, and then a long evening. After dinner he suggested we spend the night together. I was staying across the Bay, in Berkeley, with my cousin Vivian. It was late, it was raining, I was tired. I didn’t particularly like this guy, and furthermore, I had my period. I thought about this. And then I thought about waiting for the bus, which ran infrequently at that hour, about the long bus ride to Berkeley, and about the walk through the rain to my cousin’s house. The dime was the bus fare.

I had once briefly shared an apartment with a girl who was desperate to lose her virginity. She was very strange. The things that happened to me happened to girls all the time. And it was always easier to say yes. “No” was impolite. “No” would be taken personally.

“Why not?” the guy would say incredulously. “Don’t you like me?” That was a possibility so far out of the question, it had never entered his mind.

Or he might get mean: “Are you frigid?”

Such a foolish girl! So acquiescent to the imperious male. So careful of his pride. One night I let such a guy, prideful, imperious, take me to bed. He was not only married, he was impotent, and he wanted to keep trying again and again. It was extremely unpleasant. Finally, I said, “No, really, no more.” I was very nice. I didn’t mention that I was sore and exhausted and repelled. I didn’t mention that he didn’t have the wherewithal. I politely said, “Listen, I know you’re married; I don’t like one-night stands.”

He turned vicious. “You better get used to one-night stands,” he said, “because that’s all you’re ever going to have.”

You’d think that Victor might have helped me out with these situations.

After a couple of years, Bob and I got married, and I didn’t see Victor again until Bob and I separated three years later. By that time I had a boyfriend named Jack. (Yes, that Jack; the Jack who would tell me that Victor had died.) And here’s where the story gets interesting.

Jack had once been married to a girl named Sheila. Sheila was not happy in the marriage. She went to see an analyst. Guess who? Victor! And guess who Sheila was now married to? Victor! They had a little baby.

“Really?” I said.

By the way, I said to Victor, “Isn’t this situation—you, me, Jack, Sheila, all of us involved in one way and another—isn’t it, well, a problem for you, professionally speaking?”

“No problem,” Victor said. “You’ll like Sheila. She was a confused little girl when she first came to see me, but now she’s a real little woman.” He added, “You and Jack, you come and spend a weekend with us.”

Jack and I spent several weekends with Victor and Sheila. We all became good friends. Of course, I saw more of Victor than that, since he was still my analyst.

One day I told Victor I was tired of Jack.

“Ah,” Victor said.

And it seemed that due course had arrived.

Victor took my hand and led me to the daybed with the blue cotton cover. I lay down. In that position I could no longer see people walking by on the street. All I could see was Victor’s fleshy face looming over me. He murmured in my ear: “You see? You’re a real little woman now.”

Whoever You Were

I was living up on Ninety-ninth and Broadway, remember? In that studio on the fifteenth floor? Only one window, the kitchen hidden in a closet like a Murphy bed. I liked that apartment. No surprises, no one lurking in another room.

Sure, you remember that place. You lurked across the street most of that cold winter, sometimes late into the night, watching the entrance, waiting to catch the man I preferred to you.

How in God’s name did you think you’d ever spot him, anyway? Do you know how many apartments there were in that building? Sixty, seventy apartments, maybe. Men coming and going all the time. Men who lived in that building, one of whom, I’ll tell you now, was my lover. Jack. Jack, who lived one flight above me. It was a joke.

No, no, not a joke. I only made jokes because I was appalled. What had I done? And Bob, dear Bob, sweet Bob, you were out of control, you were over the edge. Crazy Bob. Remember the New Year’s Eve after I left? You rang my doorbell. Jack was with me. I was afraid to let you in, I was afraid not to. I said, “This is Jack, my upstairs neighbor.” At last you had caught me with a man, and you didn’t put two and two together. Why not? Of course, Jack was just this really short guy, not attractive, not even to me, but still, you must have wanted not to know. If you’d known, you’d have had to hit him with those brass knuckles you were carrying around. Brass knuckles! Where the hell did you get brass knuckles?

Jack left, and then we were alone. I asked you to leave too, but you wouldn’t. You were acting so nice and friendly, smiling, it was all wrong, you scared me, Bob. I went into the bathroom and locked the door. I stayed there until you finally gave up and I heard the door close behind you. Only later did I realize you’d gotten what you came for. You found my address book. You wrote down the telephone number of every man listed (there were only three or four possible candidates, weren’t there? The others were my therapist, my cousins, our friends), and you called each of them. Somehow you got a couple of them to agree to meet you, and you bought them a drink. They told me you had smiled at them in what you thought was the friendliest way, and you demanded that each one admit he was the guy. They denied it. Who wouldn’t deny it, you with your menacing smile and your right pocket bulging with brass knuckles? And then you went to see my therapist, and he told my mother, and then she started sending me clippings from the Daily Mirror: husband kills estranged wife! husband kills lover of estranged wife, estranged wife and self!

What had I done? I wasn’t used to being so effective. And I have to say, it was very exciting, the drama of it all.

Remember Lynn Bailey? Wasn’t she beautiful? So blond and delicate. Oh my God, so many years have passed I wouldn’t know her if she sat down next to me. (Would I know you now? Or you me, as far as that goes?) Lynn wanted to be a movie star, she could have been a movie star, but I guess she never made it. If not for Lynn, I might never have left you.

When Lynn came home from summer stock that fall, she was pregnant. You knew that, didn’t you? Two months pregnant. It could have been Nick’s baby: he’d gone to visit her once or twice that summer. She could have said it was Nick’s.

We were all living on West Eighteenth Street then; you and I at 359, Nick and Lynn at 361. I can see those houses as clearly as if we still lived there. I still marvel at the rent—the whole house, four floors, for $250, heat included. I remember all the places we lived and how we furnished them. I remember that awful black platform couch we bought at the Door Store, and the crewel wing chair I bought secondhand from an ad in The Village Voice. (It was $25, and I felt so smug because Harold and Joan had paid $350 at Macy’s for one exactly like it.)

The day after Lynn got home, she came over to see me. It was in early September, such a hot day. I was in the kitchen with the door to the backyard wide open. I was glad to see her; I’d missed her. She looked a little pale, though, and I said something like, Gee, Lynn, you look tired, are you okay? And she said, No, I’m pregnant. I said, Really! She just looked at me. So then I said, Do you want it? And she said, No. It’s not Nick’s. I’m not having it. I’m getting a divorce.

Adultery. Abortion. Divorce. I can’t tell you how that constellation hit me. Honestly, I think I only knew those words from novels. Lynn and Nick were our friends, they’d gotten married a few weeks before we did, they had dinner with us almost every other night, they went to the movies with us, we sat talking at Pete’s Tavern for hours. We were a foursome. If those huge words had to do with them, what about us? What about me? Was I allowed? Not that I had committed Adultery. Not yet. Not that I was Pregnant. Not yet.

We weren’t doing well, you knew that. Two years into marriage, and sex was such a sometime thing. That was my doing. Remember the time you’d been away in Chicago for a week? When you came home, I didn’t want to. And you said, “You know, I had plenty of chances in Chicago, but I wanted you.”

Yes. I knew how attractive you could be to women. Hadn’t I been one of them myself? It seemed like only yesterday I had wanted you, and all the time; I’d been desperate to marry you for three years, miserable while you went out with this one and that one—Della, Phyllis, Alice, Ruth . . . And then you capitulated. Entirely, with your whole heart you gave yourself to me, I became the one who was halfhearted. So I had what I had wanted, and I was unhappy all the time.

I’m remembering something else: a few weeks after you got home from Chicago, we went out to dinner at one of those French restaurants on Fifty-fifth or Fifty-sixth Street; Steak Frites, I think it was, there used to be so many of those cheap and decent little French restaurants then. Did we sit silently over our meal? Did we speak cold monosyllables? At one point you got up from the table, maybe you went to the bathroom or to make a phone call. The owner of the café came over to me. She said, “Did you know the gentleman sitting alone at that table?” She pointed. I turned. The table behind us was empty. I said, “No, I didn’t notice him.” She handed me an envelope. She said, “The gentleman was by himself, he said it was his birthday, and he wanted you to have this.” There was nothing written on the envelope, there was no note inside, only a ten-dollar bill. Ten dollars wasn’t a lot of money even in those days. And this is what I imagined: the man, middle-aged (he was probably younger than we are today), had watched us at our silent dinner. What did he see? A thin young girl with short dark hair, silent, sad; a redheaded man, a little older, frustrated and angry because the girl was so sullen. The observing man wanted to tell the girl something. That she was pretty? That she reminded him of someone in his past? That things would get better for her, maybe? The French restaurant, the young unhappy couple, the older man eating his lonely birthday dinner in a cheap restaurant, telling himself our story. Romantic, wasn’t it?

The Making of Me

I ran into Jack Hoffman on the street. I hadn’t seen him in ages.

We said “How are you?” and “What’s new?”

“Did you hear?” he said. “Victor’s dead. Heart attack. Five years ago.”

“Really?” I said.

“Yes,” he said. “Really.”

“Dr. Nielsen?” I said the first time I went to his office.

He nodded. He never argued with that form of address.

This was Victor Nielsen, not any sort of doctor; a former opera singer (Danish). Those were the days when anyone could hang out a shingle as a “lay” analyst.

You might expect a Dane to be tall and blond. Not so Victor. He was about fifty then, not in the least handsome, short and stocky, with a fleshy face. But he had a large head, thick gray hair, and he looked bigger sitting down. Sitting down was a major part of his job. Also he had very blue eyes; and his low, well-trained, charmingly accented voice, a beautiful voice, which gave him great authority; and in the end you had to say that, all in all, he was an attractive man.

His office was somewhere on the Upper West Side, Eighty-sixth Street, I think, just a few doors in from Broadway. It was a large room, bright, uncurtained, just above street level. Standing, you had a perfect view of the street life below; sitting, you saw the heads of people walking past the windows. I sat across the desk from Victor. (“Call me Victor,” he said, waving away any need for the spurious title.) I had expected a leather couch, but his office contained only the desk, a couple of chairs, a Marimekko sort of rug, and a daybed with a rough cotton throw, drab blue, as I remember. In due course, I thought, I would be invited to lie down.

Why was I there? Hindsight shows me that I was just ahead of the sea change. Only a few years later, a nineteen-year-old girl—confused, moody, depressed, reluctantly promiscuous—would be engulfed by a culture and a cause—drugs, casual sex, communes, Vietnam; would know what clothes to wear—

vintage dresses, army castoffs, jeans, T-shirts; would know how to do her hair—parted in the middle, flowing down her back; and would know what music belonged to her—Dylan, Baez, etc. As it was, I wore the hateful garter belts and stockings of my time, straight woolen skirts and shirtwaist dresses; set my hair every night to appear as a shoulder-length pageboy in the morning; listened to Frank Sinatra and Vaughn Monroe, who certainly weren’t bad but weren’t mine.

My mother was at her wits’ end. She consulted her cousin Sylvia, the social worker.

“I can’t deal with her,” my mother said. “She leaves school, she stays out all night, she won’t tell me where she goes, she moves out of the house, she moves back in, she can’t keep a job, she won’t talk to me.”

Sylvia, being a social worker, knew what to do. “Send her to an analyst,” she said. “I know someone.”

So now I was sitting across the desk from my analyst, and what did he say to me?

“I’m going to make a real little woman out of you.”

Once a week, over a couple of years, I saw Victor Nielsen. Apart from that promise, which he often repeated, I can’t remember another word of what passed between us. No doubt I talked about my mother, my father, and how they had ruined my life. At the time, I happened to be lovesick for a man who would marry me two years later; in the meantime, he had dumped me, and I was sleeping with almost anyone who asked. Each time I told Victor about one of these incidents, he said, “You have the makings of a real little woman.”

Who was right about this: Victor? Or my father, who had taken to calling me a prostitute?

Well of course I was not a prostitute, although I could see where he might get that idea. If he had known about it, for instance, my father could have said that I once did it for a dime. I was visiting San Francisco, and a guy whose name I no longer remember had kindly taken me to see the sights. We spent a long day together, and then a long evening. After dinner he suggested we spend the night together. I was staying across the Bay, in Berkeley, with my cousin Vivian. It was late, it was raining, I was tired. I didn’t particularly like this guy, and furthermore, I had my period. I thought about this. And then I thought about waiting for the bus, which ran infrequently at that hour, about the long bus ride to Berkeley, and about the walk through the rain to my cousin’s house. The dime was the bus fare.

I had once briefly shared an apartment with a girl who was desperate to lose her virginity. She was very strange. The things that happened to me happened to girls all the time. And it was always easier to say yes. “No” was impolite. “No” would be taken personally.

“Why not?” the guy would say incredulously. “Don’t you like me?” That was a possibility so far out of the question, it had never entered his mind.

Or he might get mean: “Are you frigid?”

Such a foolish girl! So acquiescent to the imperious male. So careful of his pride. One night I let such a guy, prideful, imperious, take me to bed. He was not only married, he was impotent, and he wanted to keep trying again and again. It was extremely unpleasant. Finally, I said, “No, really, no more.” I was very nice. I didn’t mention that I was sore and exhausted and repelled. I didn’t mention that he didn’t have the wherewithal. I politely said, “Listen, I know you’re married; I don’t like one-night stands.”

He turned vicious. “You better get used to one-night stands,” he said, “because that’s all you’re ever going to have.”

You’d think that Victor might have helped me out with these situations.

After a couple of years, Bob and I got married, and I didn’t see Victor again until Bob and I separated three years later. By that time I had a boyfriend named Jack. (Yes, that Jack; the Jack who would tell me that Victor had died.) And here’s where the story gets interesting.

Jack had once been married to a girl named Sheila. Sheila was not happy in the marriage. She went to see an analyst. Guess who? Victor! And guess who Sheila was now married to? Victor! They had a little baby.

“Really?” I said.

By the way, I said to Victor, “Isn’t this situation—you, me, Jack, Sheila, all of us involved in one way and another—isn’t it, well, a problem for you, professionally speaking?”

“No problem,” Victor said. “You’ll like Sheila. She was a confused little girl when she first came to see me, but now she’s a real little woman.” He added, “You and Jack, you come and spend a weekend with us.”

Jack and I spent several weekends with Victor and Sheila. We all became good friends. Of course, I saw more of Victor than that, since he was still my analyst.

One day I told Victor I was tired of Jack.

“Ah,” Victor said.

And it seemed that due course had arrived.

Victor took my hand and led me to the daybed with the blue cotton cover. I lay down. In that position I could no longer see people walking by on the street. All I could see was Victor’s fleshy face looming over me. He murmured in my ear: “You see? You’re a real little woman now.”

Whoever You Were

I was living up on Ninety-ninth and Broadway, remember? In that studio on the fifteenth floor? Only one window, the kitchen hidden in a closet like a Murphy bed. I liked that apartment. No surprises, no one lurking in another room.

Sure, you remember that place. You lurked across the street most of that cold winter, sometimes late into the night, watching the entrance, waiting to catch the man I preferred to you.

How in God’s name did you think you’d ever spot him, anyway? Do you know how many apartments there were in that building? Sixty, seventy apartments, maybe. Men coming and going all the time. Men who lived in that building, one of whom, I’ll tell you now, was my lover. Jack. Jack, who lived one flight above me. It was a joke.

No, no, not a joke. I only made jokes because I was appalled. What had I done? And Bob, dear Bob, sweet Bob, you were out of control, you were over the edge. Crazy Bob. Remember the New Year’s Eve after I left? You rang my doorbell. Jack was with me. I was afraid to let you in, I was afraid not to. I said, “This is Jack, my upstairs neighbor.” At last you had caught me with a man, and you didn’t put two and two together. Why not? Of course, Jack was just this really short guy, not attractive, not even to me, but still, you must have wanted not to know. If you’d known, you’d have had to hit him with those brass knuckles you were carrying around. Brass knuckles! Where the hell did you get brass knuckles?

Jack left, and then we were alone. I asked you to leave too, but you wouldn’t. You were acting so nice and friendly, smiling, it was all wrong, you scared me, Bob. I went into the bathroom and locked the door. I stayed there until you finally gave up and I heard the door close behind you. Only later did I realize you’d gotten what you came for. You found my address book. You wrote down the telephone number of every man listed (there were only three or four possible candidates, weren’t there? The others were my therapist, my cousins, our friends), and you called each of them. Somehow you got a couple of them to agree to meet you, and you bought them a drink. They told me you had smiled at them in what you thought was the friendliest way, and you demanded that each one admit he was the guy. They denied it. Who wouldn’t deny it, you with your menacing smile and your right pocket bulging with brass knuckles? And then you went to see my therapist, and he told my mother, and then she started sending me clippings from the Daily Mirror: husband kills estranged wife! husband kills lover of estranged wife, estranged wife and self!

What had I done? I wasn’t used to being so effective. And I have to say, it was very exciting, the drama of it all.

Remember Lynn Bailey? Wasn’t she beautiful? So blond and delicate. Oh my God, so many years have passed I wouldn’t know her if she sat down next to me. (Would I know you now? Or you me, as far as that goes?) Lynn wanted to be a movie star, she could have been a movie star, but I guess she never made it. If not for Lynn, I might never have left you.

When Lynn came home from summer stock that fall, she was pregnant. You knew that, didn’t you? Two months pregnant. It could have been Nick’s baby: he’d gone to visit her once or twice that summer. She could have said it was Nick’s.

We were all living on West Eighteenth Street then; you and I at 359, Nick and Lynn at 361. I can see those houses as clearly as if we still lived there. I still marvel at the rent—the whole house, four floors, for $250, heat included. I remember all the places we lived and how we furnished them. I remember that awful black platform couch we bought at the Door Store, and the crewel wing chair I bought secondhand from an ad in The Village Voice. (It was $25, and I felt so smug because Harold and Joan had paid $350 at Macy’s for one exactly like it.)

The day after Lynn got home, she came over to see me. It was in early September, such a hot day. I was in the kitchen with the door to the backyard wide open. I was glad to see her; I’d missed her. She looked a little pale, though, and I said something like, Gee, Lynn, you look tired, are you okay? And she said, No, I’m pregnant. I said, Really! She just looked at me. So then I said, Do you want it? And she said, No. It’s not Nick’s. I’m not having it. I’m getting a divorce.

Adultery. Abortion. Divorce. I can’t tell you how that constellation hit me. Honestly, I think I only knew those words from novels. Lynn and Nick were our friends, they’d gotten married a few weeks before we did, they had dinner with us almost every other night, they went to the movies with us, we sat talking at Pete’s Tavern for hours. We were a foursome. If those huge words had to do with them, what about us? What about me? Was I allowed? Not that I had committed Adultery. Not yet. Not that I was Pregnant. Not yet.

We weren’t doing well, you knew that. Two years into marriage, and sex was such a sometime thing. That was my doing. Remember the time you’d been away in Chicago for a week? When you came home, I didn’t want to. And you said, “You know, I had plenty of chances in Chicago, but I wanted you.”

Yes. I knew how attractive you could be to women. Hadn’t I been one of them myself? It seemed like only yesterday I had wanted you, and all the time; I’d been desperate to marry you for three years, miserable while you went out with this one and that one—Della, Phyllis, Alice, Ruth . . . And then you capitulated. Entirely, with your whole heart you gave yourself to me, I became the one who was halfhearted. So I had what I had wanted, and I was unhappy all the time.

I’m remembering something else: a few weeks after you got home from Chicago, we went out to dinner at one of those French restaurants on Fifty-fifth or Fifty-sixth Street; Steak Frites, I think it was, there used to be so many of those cheap and decent little French restaurants then. Did we sit silently over our meal? Did we speak cold monosyllables? At one point you got up from the table, maybe you went to the bathroom or to make a phone call. The owner of the café came over to me. She said, “Did you know the gentleman sitting alone at that table?” She pointed. I turned. The table behind us was empty. I said, “No, I didn’t notice him.” She handed me an envelope. She said, “The gentleman was by himself, he said it was his birthday, and he wanted you to have this.” There was nothing written on the envelope, there was no note inside, only a ten-dollar bill. Ten dollars wasn’t a lot of money even in those days. And this is what I imagined: the man, middle-aged (he was probably younger than we are today), had watched us at our silent dinner. What did he see? A thin young girl with short dark hair, silent, sad; a redheaded man, a little older, frustrated and angry because the girl was so sullen. The observing man wanted to tell the girl something. That she was pretty? That she reminded him of someone in his past? That things would get better for her, maybe? The French restaurant, the young unhappy couple, the older man eating his lonely birthday dinner in a cheap restaurant, telling himself our story. Romantic, wasn’t it?

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherRandom House Trade Paperbacks

- Publication date2007

- ISBN 10 0812972651

- ISBN 13 9780812972658

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages352

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 251.00

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Life Stories: How I Came Into My Inheritance Strangers in the House

Published by

Random House Trade Paperbacks

(2007)

ISBN 10: 0812972651

ISBN 13: 9780812972658

New

Paperback

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0812972651

Buy New

US$ 251.00

Convert currency

Life Stories: How I Came Into My Inheritance Strangers in the House

Published by

Random House Trade Paperbacks

(2007)

ISBN 10: 0812972651

ISBN 13: 9780812972658

New

Paperback

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0812972651

Buy New

US$ 253.13

Convert currency

Life Stories: How I Came Into My Inheritance Strangers in the House

Published by

Random House Trade Paperbacks

(2007)

ISBN 10: 0812972651

ISBN 13: 9780812972658

New

Paperback

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0812972651

Buy New

US$ 254.79

Convert currency