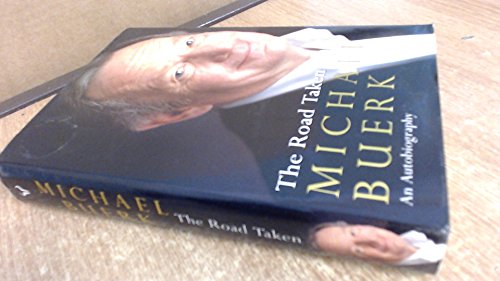

Items related to The Road Taken

'Dawn, and as the sun breaks through the piercing chill of night on the plain outside Korem it lights up a biblical famine, now, in the Twentieth Century.' Those words opened Michael Buerk's first report on the Ethiopian famine for the 6 o'clock news on October 24th 1984. His reports sent shock waves round the world. Hundreds of millions of pounds were raised and millions of lives were saved. The Live Aid concert, a direct consequence of Bob Geldof watching that broadcast, was watched by half the planet.

Michael Buerk has reported on some of the biggest stories in our lifetime: the Flixborough chemical plant fire, the Birmingham pub bombing, Lockerbie. He was in Buenos Aires at the start of the Falklands War; he reported the death throes of apartheid in South Africa.

He has been the face of the BBC flagship evening news for many years and has fronted everything from the popular BBC1 series 999 to the erudite Radio 4 programme The Moral Maze.

He has won every major award and is universally admired and respected for his intelligent and honest journalism.

He is also loved by his colleagues, not least for his wicked sense of humour. His accounts of his first live radio report as a young reporter competing with the town drunk and his producer's solution to the problem of an uncontrollable panel on the Moral Maze are a joy to read.

He also reveals the private Michael Buerk, his bigamist father, his long and happy marriage to Christine, his delight at fatherhood.

From the Hardcover edition.

Michael Buerk has reported on some of the biggest stories in our lifetime: the Flixborough chemical plant fire, the Birmingham pub bombing, Lockerbie. He was in Buenos Aires at the start of the Falklands War; he reported the death throes of apartheid in South Africa.

He has been the face of the BBC flagship evening news for many years and has fronted everything from the popular BBC1 series 999 to the erudite Radio 4 programme The Moral Maze.

He has won every major award and is universally admired and respected for his intelligent and honest journalism.

He is also loved by his colleagues, not least for his wicked sense of humour. His accounts of his first live radio report as a young reporter competing with the town drunk and his producer's solution to the problem of an uncontrollable panel on the Moral Maze are a joy to read.

He also reveals the private Michael Buerk, his bigamist father, his long and happy marriage to Christine, his delight at fatherhood.

From the Hardcover edition.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Born in Solihull in 1946, Michael Buerk began his journalistic career at the Bromsgrove Weekly Messenger. Now as the presenter of The Moral Maze as well as The Choice, he is one of the leading figures at the BBC. He lives in Guildford with his wife and has twin boys who both work as journalists.

From the Hardcover edition.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

From the Hardcover edition.

ONE

We were right on top of it when it went up, but none of us heard the bang. None of us who survived, anyway.

It brought people out from their homes and their hiding places for twenty miles around, wondering if a nuclear bomb had gone off. That’s what it looked like. A great tower of black smoke, a kilometre wide, rushing up from the southern suburbs of the city to smear itself across the bottom of the clouds. The blackness was lined with fire and shot through by a fountain of smaller explosions that arched up into the gloom and fell, miles away, in a crackling, golden rain.

They say what happened that morning in Addis Ababa was the biggest explosion in Africa in the history of man. We were only a couple of hundred yards away, four flimsy humans caught out in the open. Without warning, before our eyes could register, or our brains comprehend, what was happening, we were flung to our separate fates. We had been almost close enough to touch each other. One was killed instantly. One was terribly mutilated. One was blasted straight into unconsciousness.

I was the fourth. I had a brief moment of awareness; a sense of flying, or at any rate being airborne, in clouds of brown dust and singing metal. But, instead of hitting the ground, something very odd happened. My mind seemed to jettison the body, like the last stage of a space mission. I was suddenly in some parallel universe where time ran backwards, as well as forwards, in a jerky and random series of flashbacks. They made no overall sense, but they were vivid and overwhelming. They were like the closing credits of a film after the audience had left. Or how it is meant to be when you are drowning. To be honest, I thought: This is what it is to die.

I could tell the memories were authentic, though the unhappy ones, which had long been buried, seemed unfamiliar at first. They were all startlingly clear yet, at the same time, distant, out of reach. They were exactly like the early 3D slides I saw, much later, in a museum in Berlin. You look through eyepieces that shut out everything else, and a central European street scene from a hundred years ago leaps at you. It catches at your breath because it is so real, yet it’s in a different dimension; somewhere halfway between the present and the past. There’s a wheel at the side. Each time you turn it, it clicks you on, into a new scene and a new mood, entirely disconnected from the one before. One moment it’s all sadness, then it’s fearful, then it flicks you straight into a wild celebration. You instantly identify with what is both so near and yet so impossibly far away. It was just like that, that morning in Addis Ababa.

Click.

The first picture is almost all grey. Grey sky, the grey decks of a great grey liner as it ploughs the grey Atlantic on its way back, though I am far too young to know it, to a grey post-war Britain. The only splash of colour is the orange of a child’s life jacket. It is far too large for me, for the three-year-old Michael Buerk who is fleeing with his mother from her doomed marriage in Vancouver. It was a marriage that had begun in bigamy and is ending in pain, recrimination, and legal fees neither can afford. My mother, seasick in our cabin below, is escaping back to her parents. My father, it turns out later, is looking for a more dramatic way out. He’s flying north, to Yellowknife in the Northwest Territories, to a cheap hotel room where he’s going to slash his wrists. It will be halfhearted and none too successful, rather like the rest of his life. He will marry the pretty nurse who pulls him round, and that’s typical, too. He’s the marrying kind.

That’s not in this first picture, though. That’s just a little boy in a big ship, alone and rather lost.

Click.

Now it’s two small boys. My boys. This time the colours are vivid. Blond hair, small sweaters in stripes of primary yellows and greens, blue dungarees, surrounded by toys that are mostly cherry red. They are identical twins at that wonderful, staggery, eighteen-month stage. Pulling themselves up, collapsing down again, giggling and hooting into each other’s faces, into the living mirror of themselves. Only their mother and father could possibly be happier than they are. After all, we can remember what they cannot, what is for them a lifetime away but, to us, seems only yesterday. The two of them, pink and plucked-looking, muffled and inert in the incubators of the intensive care unit. We had bent over them, racked with worry and surrounded by whispered concerns, day after day. First, they might not live. Then they might survive, but be damaged by the trauma of their birth. How could we have thought that, looking at them now?

There is no joy more complete and more selfless than the selfish joys of early parenthood.

Click.

A pale figure is trying to hide in the pools of darkness between the street lamps on a city centre pavement. Fat chance. Every few seconds he is swept by the headlights of a passing car. Some swerve and blow their horns. Some of the drivers lean out and yell at him, coarse or funny he cannot tell above the din of the traffic and his own rising sense of panic. It is not every night you see a man creeping, stark naked, through one of the smarter parts of even such a lively and liberal city as Bristol. Besides, isn’t it that bloke off the telly? Oh, God, it is, it is . . .

Click.

Back in a childhood summer. Under a tree in the fields at Ravenscroft, sitting by my bike, trying to take in the news that my mother was going to die. I was sixteen that summer. I didn’t know what to say or even how to feel. I had known she was ill but you never think your parents can die, especially when you only have one.

I was there again the day she died, rather than with her. They had thought it best I shouldn’t go. They thought it best I shouldn’t go to the funeral either. I still don’t know why I agreed, except that I was dazed and uncertain, and stayed that way for months. Later I would sometimes feel I traded in death. Odd I should have had so little connection with the death that meant most of all to me.

Click.

A nuclear landscape around the flaming ruins of the chemical plant. The smoke is blotting out what remains of the daylight and is being flayed by the rotor blades of the helicopter that brought us. The air we are breathing is stiff with phenyls. And the image you can never forget, that was bound to come to the top of the shuffled cards of memory: a steaming lake of chemicals, brewed up by the explosion, and, out of the middle, a man’s leg. It’s bent at the knee and the boot points like a signpost to what’s left of the Nypro plant at Flixborough.

Click.

Faster now.

The pub was blown apart by the IRA earlier in the evening. The walls are pocked with debris, and spattered with blood and human remains. They had pushed the bomb under a table in the bar. When it went off it blasted the sixties tubular furniture through the soft flesh of the laughing crowd. What is left now looks like a stage set from hell. I am seeing it through the window of a taxi, suddenly aware that my hand, on the door handle, is sticky with blood. The taxi, like many others in Birmingham that night, had been used as a makeshift ambulance to take the dead and the dying away from the Tavern in the Town.

Click.

The light is blinding. It is midday and the African sun, shining out of a dry, blue Highveld winter, casts no shadows from the shacks that line the dirt road. There is nothing to shade or cover the puddle that once was a human being. The ‘necklace’ is a cruel way to kill; it is meant to terrify. This is exemplary punishment for a young man caught informing on the township ‘comrades’ to the white policemen.

An hour ago, he was a frightened teenager at the centre of a crowd that mocked and prodded him. Then they pushed a tyre over his head and his shoulders. They filled it with petrol and set it alight. He jerked and screamed a full minute before he died and, quite literally, began to melt. Now the comrades, his schoolmates, laugh and dance, pointing at the unrecognisable mess spreading across the dirt. Some wave tyres at the white reporter who has just been violently sick in the scrub at the side of the road.

Click.

Faster still and, though the fleeting images have no theme, there are connections, short-circuits in the subconscious.

A local radio studio. Four of us round the familiar green baize table and its old-fashioned BBC microphone. The first news programme I ever presented. The first disaster. Two minutes in, and the tickle at the back of my throat has become a full-scale nose bleed. At first, it only covers the typewritten scripts in front of me, but as I continue talking it sprays everywhere, splattering a fellow reporter and two local worthies on the other side of the table.

Click.

A bigger radio studio, thirty years on. The panel of the Moral Maze have worked themselves into a terrible state over the iniquities of modern sexual ethics. The ‘lively debate’ has turned into a pretty vicious quarrel the chairman can do little to moderate and less to bring to an end, which is a problem with only fifty-five seconds to go. The studio door has banged open and the veteran producer stands in front of us, impressively tall and distinguished with his natty suiting and trademark silver hair. Slowly he is unzipping his fly. The quarrel dies away in a second. The problem now is that everybody has stopped speaking, the women in horror, the men choking with unseemly, schoolboy mirth. The silence goes on so long Radio Four is worried the transmitter has failed.

Click.

The television studio is a flurry of banging doors, with the main news programme of the evening only seconds away and the big breaking story only five minutes old. Is it the night the Chancellor resigns, or an airliner’s exploded over Lockerbie, or maybe the evening the Israeli Prime Minister is assassinated? It is a rare night – perhaps two or three times a year – when one of the easiest jobs in the world, basically a matter of reading out loud, becomes a great deal more difficult. Very little is known, but the quick rumours have solidified into one doubly confirmed fact. Reporters and cameramen are being scrambled in all directions, producers are working on library material, graphics and maps. Potential interviewees are being tracked down. But there’s not much to go on, and not much to go to. The plastic in your ear begins to count: five, four, three, two, one . . .

Click.

Back in Africa. A room with a dirt floor opening out on to the road, the main spinal highway that runs north from Addis towards Tigre and Eritrea. This is Korem, little more than a village straggling along the road, and the epicentre of the twentieth century’s worst famine. We had been filming all morning, among the dead and the dying camped out on the plain beyond the town, and had come searching for water to the house that was used as a sort of primitive café. We had not expected food here in the land of starving, but they offered to sell us a couple of pieces of bread that they pushed across the makeshift counter.

There was a rustling behind us. Somebody coughed. While we had been talking a crowd had gathered at the doorway. Emaciated men and women and children – so many of them that they are filling up the road outside. As I reach for the bread a ragged old man in the doorway, at the front of the crowd, sinks to his knees and shuffles across the beaten dirt floor. He raises his hands high above his pleading eyes in the most abject beggary.

Is this what life amounts to, once it has been lived? A jumble of disconnected memories, mere snapshots of fun and fear, embarrassment and other people’s pain. Where’s the continuity and the context that made sense of it all? A worrying thought. Perhaps it never did.

Click.

This is recent. Only two days ago. One of the sidebar tragedies of war. The tide of fighting had ebbed back from this part of the outskirts of Addis and left nobody to guard the ammunition depot that stood there. The local people were poor and hungry. They had broken into the factory looking for things to steal, first in ones and twos, then in dozens, finally in hundreds. When somebody inadvertently struck a spark that blew the place to bits there were 800 people inside and they were all killed. It had happened several days before. They are still lying all around now, blown inside out by the force of the explosion, pale entrails ballooning outside blackened skins. The stench of death hits you in the face. We’ve copied the few locals who are picking in the ruins and pushed grass and coarse brown herbs up our nostrils to try to keep it out. It’s probably the most awful thing I have ever seen.

Only 48 hours ago, and now it has happened to me.

Click.

My eyes open. I am back in the real world, and it is worse.

From the Hardcover edition.

We were right on top of it when it went up, but none of us heard the bang. None of us who survived, anyway.

It brought people out from their homes and their hiding places for twenty miles around, wondering if a nuclear bomb had gone off. That’s what it looked like. A great tower of black smoke, a kilometre wide, rushing up from the southern suburbs of the city to smear itself across the bottom of the clouds. The blackness was lined with fire and shot through by a fountain of smaller explosions that arched up into the gloom and fell, miles away, in a crackling, golden rain.

They say what happened that morning in Addis Ababa was the biggest explosion in Africa in the history of man. We were only a couple of hundred yards away, four flimsy humans caught out in the open. Without warning, before our eyes could register, or our brains comprehend, what was happening, we were flung to our separate fates. We had been almost close enough to touch each other. One was killed instantly. One was terribly mutilated. One was blasted straight into unconsciousness.

I was the fourth. I had a brief moment of awareness; a sense of flying, or at any rate being airborne, in clouds of brown dust and singing metal. But, instead of hitting the ground, something very odd happened. My mind seemed to jettison the body, like the last stage of a space mission. I was suddenly in some parallel universe where time ran backwards, as well as forwards, in a jerky and random series of flashbacks. They made no overall sense, but they were vivid and overwhelming. They were like the closing credits of a film after the audience had left. Or how it is meant to be when you are drowning. To be honest, I thought: This is what it is to die.

I could tell the memories were authentic, though the unhappy ones, which had long been buried, seemed unfamiliar at first. They were all startlingly clear yet, at the same time, distant, out of reach. They were exactly like the early 3D slides I saw, much later, in a museum in Berlin. You look through eyepieces that shut out everything else, and a central European street scene from a hundred years ago leaps at you. It catches at your breath because it is so real, yet it’s in a different dimension; somewhere halfway between the present and the past. There’s a wheel at the side. Each time you turn it, it clicks you on, into a new scene and a new mood, entirely disconnected from the one before. One moment it’s all sadness, then it’s fearful, then it flicks you straight into a wild celebration. You instantly identify with what is both so near and yet so impossibly far away. It was just like that, that morning in Addis Ababa.

Click.

The first picture is almost all grey. Grey sky, the grey decks of a great grey liner as it ploughs the grey Atlantic on its way back, though I am far too young to know it, to a grey post-war Britain. The only splash of colour is the orange of a child’s life jacket. It is far too large for me, for the three-year-old Michael Buerk who is fleeing with his mother from her doomed marriage in Vancouver. It was a marriage that had begun in bigamy and is ending in pain, recrimination, and legal fees neither can afford. My mother, seasick in our cabin below, is escaping back to her parents. My father, it turns out later, is looking for a more dramatic way out. He’s flying north, to Yellowknife in the Northwest Territories, to a cheap hotel room where he’s going to slash his wrists. It will be halfhearted and none too successful, rather like the rest of his life. He will marry the pretty nurse who pulls him round, and that’s typical, too. He’s the marrying kind.

That’s not in this first picture, though. That’s just a little boy in a big ship, alone and rather lost.

Click.

Now it’s two small boys. My boys. This time the colours are vivid. Blond hair, small sweaters in stripes of primary yellows and greens, blue dungarees, surrounded by toys that are mostly cherry red. They are identical twins at that wonderful, staggery, eighteen-month stage. Pulling themselves up, collapsing down again, giggling and hooting into each other’s faces, into the living mirror of themselves. Only their mother and father could possibly be happier than they are. After all, we can remember what they cannot, what is for them a lifetime away but, to us, seems only yesterday. The two of them, pink and plucked-looking, muffled and inert in the incubators of the intensive care unit. We had bent over them, racked with worry and surrounded by whispered concerns, day after day. First, they might not live. Then they might survive, but be damaged by the trauma of their birth. How could we have thought that, looking at them now?

There is no joy more complete and more selfless than the selfish joys of early parenthood.

Click.

A pale figure is trying to hide in the pools of darkness between the street lamps on a city centre pavement. Fat chance. Every few seconds he is swept by the headlights of a passing car. Some swerve and blow their horns. Some of the drivers lean out and yell at him, coarse or funny he cannot tell above the din of the traffic and his own rising sense of panic. It is not every night you see a man creeping, stark naked, through one of the smarter parts of even such a lively and liberal city as Bristol. Besides, isn’t it that bloke off the telly? Oh, God, it is, it is . . .

Click.

Back in a childhood summer. Under a tree in the fields at Ravenscroft, sitting by my bike, trying to take in the news that my mother was going to die. I was sixteen that summer. I didn’t know what to say or even how to feel. I had known she was ill but you never think your parents can die, especially when you only have one.

I was there again the day she died, rather than with her. They had thought it best I shouldn’t go. They thought it best I shouldn’t go to the funeral either. I still don’t know why I agreed, except that I was dazed and uncertain, and stayed that way for months. Later I would sometimes feel I traded in death. Odd I should have had so little connection with the death that meant most of all to me.

Click.

A nuclear landscape around the flaming ruins of the chemical plant. The smoke is blotting out what remains of the daylight and is being flayed by the rotor blades of the helicopter that brought us. The air we are breathing is stiff with phenyls. And the image you can never forget, that was bound to come to the top of the shuffled cards of memory: a steaming lake of chemicals, brewed up by the explosion, and, out of the middle, a man’s leg. It’s bent at the knee and the boot points like a signpost to what’s left of the Nypro plant at Flixborough.

Click.

Faster now.

The pub was blown apart by the IRA earlier in the evening. The walls are pocked with debris, and spattered with blood and human remains. They had pushed the bomb under a table in the bar. When it went off it blasted the sixties tubular furniture through the soft flesh of the laughing crowd. What is left now looks like a stage set from hell. I am seeing it through the window of a taxi, suddenly aware that my hand, on the door handle, is sticky with blood. The taxi, like many others in Birmingham that night, had been used as a makeshift ambulance to take the dead and the dying away from the Tavern in the Town.

Click.

The light is blinding. It is midday and the African sun, shining out of a dry, blue Highveld winter, casts no shadows from the shacks that line the dirt road. There is nothing to shade or cover the puddle that once was a human being. The ‘necklace’ is a cruel way to kill; it is meant to terrify. This is exemplary punishment for a young man caught informing on the township ‘comrades’ to the white policemen.

An hour ago, he was a frightened teenager at the centre of a crowd that mocked and prodded him. Then they pushed a tyre over his head and his shoulders. They filled it with petrol and set it alight. He jerked and screamed a full minute before he died and, quite literally, began to melt. Now the comrades, his schoolmates, laugh and dance, pointing at the unrecognisable mess spreading across the dirt. Some wave tyres at the white reporter who has just been violently sick in the scrub at the side of the road.

Click.

Faster still and, though the fleeting images have no theme, there are connections, short-circuits in the subconscious.

A local radio studio. Four of us round the familiar green baize table and its old-fashioned BBC microphone. The first news programme I ever presented. The first disaster. Two minutes in, and the tickle at the back of my throat has become a full-scale nose bleed. At first, it only covers the typewritten scripts in front of me, but as I continue talking it sprays everywhere, splattering a fellow reporter and two local worthies on the other side of the table.

Click.

A bigger radio studio, thirty years on. The panel of the Moral Maze have worked themselves into a terrible state over the iniquities of modern sexual ethics. The ‘lively debate’ has turned into a pretty vicious quarrel the chairman can do little to moderate and less to bring to an end, which is a problem with only fifty-five seconds to go. The studio door has banged open and the veteran producer stands in front of us, impressively tall and distinguished with his natty suiting and trademark silver hair. Slowly he is unzipping his fly. The quarrel dies away in a second. The problem now is that everybody has stopped speaking, the women in horror, the men choking with unseemly, schoolboy mirth. The silence goes on so long Radio Four is worried the transmitter has failed.

Click.

The television studio is a flurry of banging doors, with the main news programme of the evening only seconds away and the big breaking story only five minutes old. Is it the night the Chancellor resigns, or an airliner’s exploded over Lockerbie, or maybe the evening the Israeli Prime Minister is assassinated? It is a rare night – perhaps two or three times a year – when one of the easiest jobs in the world, basically a matter of reading out loud, becomes a great deal more difficult. Very little is known, but the quick rumours have solidified into one doubly confirmed fact. Reporters and cameramen are being scrambled in all directions, producers are working on library material, graphics and maps. Potential interviewees are being tracked down. But there’s not much to go on, and not much to go to. The plastic in your ear begins to count: five, four, three, two, one . . .

Click.

Back in Africa. A room with a dirt floor opening out on to the road, the main spinal highway that runs north from Addis towards Tigre and Eritrea. This is Korem, little more than a village straggling along the road, and the epicentre of the twentieth century’s worst famine. We had been filming all morning, among the dead and the dying camped out on the plain beyond the town, and had come searching for water to the house that was used as a sort of primitive café. We had not expected food here in the land of starving, but they offered to sell us a couple of pieces of bread that they pushed across the makeshift counter.

There was a rustling behind us. Somebody coughed. While we had been talking a crowd had gathered at the doorway. Emaciated men and women and children – so many of them that they are filling up the road outside. As I reach for the bread a ragged old man in the doorway, at the front of the crowd, sinks to his knees and shuffles across the beaten dirt floor. He raises his hands high above his pleading eyes in the most abject beggary.

Is this what life amounts to, once it has been lived? A jumble of disconnected memories, mere snapshots of fun and fear, embarrassment and other people’s pain. Where’s the continuity and the context that made sense of it all? A worrying thought. Perhaps it never did.

Click.

This is recent. Only two days ago. One of the sidebar tragedies of war. The tide of fighting had ebbed back from this part of the outskirts of Addis and left nobody to guard the ammunition depot that stood there. The local people were poor and hungry. They had broken into the factory looking for things to steal, first in ones and twos, then in dozens, finally in hundreds. When somebody inadvertently struck a spark that blew the place to bits there were 800 people inside and they were all killed. It had happened several days before. They are still lying all around now, blown inside out by the force of the explosion, pale entrails ballooning outside blackened skins. The stench of death hits you in the face. We’ve copied the few locals who are picking in the ruins and pushed grass and coarse brown herbs up our nostrils to try to keep it out. It’s probably the most awful thing I have ever seen.

Only 48 hours ago, and now it has happened to me.

Click.

My eyes open. I am back in the real world, and it is worse.

From the Hardcover edition.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHutchinson

- Publication date2004

- ISBN 10 0091799678

- ISBN 13 9780091799670

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages456

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 32.34

Shipping:

US$ 13.82

From United Kingdom to U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

THE ROAD TAKEN

Published by

HUTCHINSON

(2004)

ISBN 10: 0091799678

ISBN 13: 9780091799670

New

Hardcover

First Edition

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. 1st Edition. THE ROAD TAKEN.Michael Buerk.Condition:New,may have slight shelf wear. Seller Inventory # 005259

Buy New

US$ 32.34

Convert currency

The Road Taken

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 0091799678-2-1

Buy New

US$ 84.63

Convert currency