Items related to Red Sorghum

Synopsis

Spanning three generations, this novel of family and myth is told through a series of flashbacks that depict events of staggering horror set against a landscape of gemlike beauty as the Chinese battle both the Japanese invaders and each other in the turbulent 1930s. As the novel opens, a group of villagers, led by Commander Yu, the narrator's grandfather, prepare to attack the advancing Japanese. Yu sends his 14-year-old son back home to get food for his men; but as Yu's wife returns through the sorghum fields with the food, the Japanese start firing and she is killed. Her death becomes the thread that links the past to the present and the narrator moves back and forth recording the war's progress, the fighting between the Chinese warlords and his family's history.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

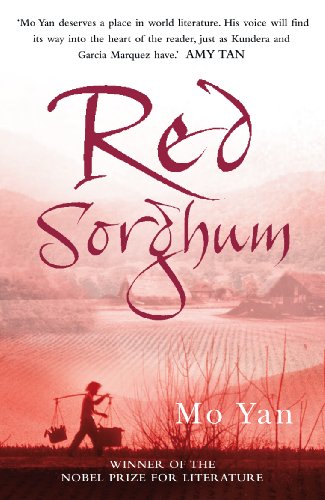

Mo Yan was born in 1956 in Shandong, northeastern China. The author of over forty short stories and five novels, he is the most critically acclaimed Chinese writer of his generation, in both China and the West. The critically acclaimed film version of the novel, Red Sorghum, won first prize in the Golden Bear Awards at the Berlin Film Festival in 1988. He won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2012.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Spectacular reviews for

Red Sorghum

“Red Sorghum creates the backdrop for mythic heroism and primitivist vitality through the exotically portrayed setting of Shandong’s lush sorghum fields.”

—The Boston Globe

“[Yan’s] style is vibrant, alternating between lyrical passages and an oddly conversational tone. This historical tale has a remarkable sense of immediacy and an impressive scope.”

—Los Angeles Times

“Having read Red Sorghum, I believe Mo Yan deserves a place in world literature. His imagery is astounding, sensual and visceral. His story is electrifying and epic. I was amazed from the first page. It is unlike anything I’ve read coming out of China in past or recent times. I am convinced this book will successfully leap over the international boundaries that many translated works face. . . . This is an important work from an important writer.”

—Amy Tan

“Mo Yan spares us nothing . . . Red Sorghum fixes our attention on a series of exquisite images . . . [as] he paints his pictures of a world in chaos, where every day is a struggle to preserve life, if not honor, and there is no safety even in death.”

—New York Magazine

“Red Sorghum is so unlike any other piece of contemporary Chinese literature that, were it not so clearly set in China, one might imagine it to be a product of another place and time. . . . With this work Mo Yan has helped his country find a new and powerfully convincing literary voice.”

—Orville Schell

“A masterful translation . . . The appearance of Red Sorghum is an important event for English-language literature, one which bids well for the power and influence of Chinese fiction in the 21st century.”

—Richmond Times Dispatch

“Yan tempers his brutal tale with a powerfully evocative lyricism . . . A powerful new voice on the brutal unrest of rural China in the late ’20s and ’30s.”

—Kirkus Reviews

PENGUIN BOOKS

RED SORGHUM

Mo Yan (literally “don’t speak”) is the pen name of Guan Moye. Born in 1955 to a peasant family in Shandong province, he is the author of ten novels including Red Sorghum, which was made into a feature film, dozens of novellas, and hundreds of short stories. Mo Yan is the winner of the 2012 Nobel Prize in Literature and the 2009 Newman Prize for Chinese Literature. He has won virtually every Chinese literary prize, including the Mao Dun Literature Prize in 2011 (China’s most prestigious literary award) and is the most critically acclaimed Chinese writer of his generation, in both China and around the world. He lives in Beijing.

Howard Goldblatt is the foremost translator of modern and contemporary Chinese literature in the West. The founding editor of the journal Modern Chinese Literature, he has written for The Washington Post, The Times of London, Time, World Literature Today, and the Los Angeles Times. He is currently a professor at the University of Notre Dame.

MO YAN

Red

Sorghum

A NOVEL OF CHINA

Translated from the Chinese

by Howard Goldblatt

PENGUIN BOOKS

WITH THIS BOOK I respectfully invoke the heroic, aggrieved souls wandering in the boundless bright-red sorghum fields of my hometown. As your unfilial son, I am prepared to carve out my heart, marinate it in soy sauce, have it minced and placed in three bowls, and lay it out as an offering in a field of sorghum. Partake of it in good health!

Table of Contents

CHAPTER ONE

Red Sorghum

1

THE NINTH DAY of the eighth lunar month, 1939. My father, a bandit’s offspring who had passed his fifteenth birthday, was joining the forces of Commander Yu Zhan’ao, a man destined to become a legendary hero, to ambush a Japanese convoy on the Jiao-Ping highway. Grandma, a padded jacket over her shoulders, saw them to the edge of the village. “Stop here,” Commander Yu ordered her. She stopped.

“Douguan, mind your foster-dad,” she told my father. The sight of her large frame and the warm fragrance of her lined jacket chilled him. He shivered. His stomach growled.

Commander Yu patted him on the head and said, “Let’s go, foster-son.”

Heaven and earth were in turmoil, the view was blurred. By then the soldiers’ muffled footsteps had moved far down the road. Father could still hear them, but a curtain of blue mist obscured the men themselves. Gripping tightly to Commander Yu’s coat, he nearly flew down the path on churning legs. Grandma receded like a distant shore as the approaching sea of mist grew more tempestuous, holding on to Commander Yu was like clinging to the railing of a boat.

That was how Father rushed toward the uncarved granite marker that would rise above his grave in the bright-red sorghum fields of his hometown. A bare-assed little boy once led a white billy goat up to the weed-covered grave, and as it grazed in unhurried contentment, the boy pissed furiously on the grave and sang out: “The sorghum is red—the Japanese are coming—compatriots, get ready—fire your rifles and cannons—”

Someone said that the little goatherd was me, but I don’t know. I had learned to love Northeast Gaomi Township with all my heart, and to hate it with unbridled fury. I didn’t realize until I’d grown up that Northeast Gaomi Township is easily the most beautiful and most repulsive, most unusual and most common, most sacred and most corrupt, most heroic and most bastardly, hardest-drinking and hardest-loving place in the world. The people of my father’s generation who lived there ate sorghum out of preference, planting as much of it as they could. In late autumn, during the eighth lunar month, vast stretches of red sorghum shimmered like a sea of blood. Tall and dense, it reeked of glory; cold and graceful, it promised enchantment; passionate and loving, it was tumultuous.

The autumn winds are cold and bleak, the sun’s rays intense. White clouds, full and round, float in the tile-blue sky, casting full round purple shadows onto the sorghum fields below. Over decades that seem but a moment in time, lines of scarlet figures shuttled among the sorghum stalks to weave a vast human tapestry. They killed, they looted, and they defended their country in a valiant, stirring ballet that makes us unfilial descendants who now occupy the land pale by comparison. Surrounded by progress, I feel a nagging sense of our species’ regression.

After leaving the village, the troops marched down a narrow dirt path, the tramping of their feet merging with the rustling of weeds. The heavy mist was strangely animated, kaleidoscopic. Tiny droplets of water pooled into large drops on Father’s face; clumps of hair stuck to his forehead. He was used to the delicate peppermint aroma and the slightly sweet yet pungent odor of ripe sorghum wafting over from the sides of the path—nothing new there. But as they marched through the heavy mist, his nose detected a new, sickly-sweet odor, neither yellow nor red, blending with the smells of peppermint and sorghum to call up memories hidden deep in his soul.

Six days later, the fifteenth day of the eighth month, the night of the Mid-Autumn Festival. A bright round moon climbed slowly in the sky above the solemn, silent sorghum fields, bathing the tassels in its light until they shimmered like mercury. Among the chiseled flecks of moonlight Father caught a whiff of the same sickly odor, far stronger than anything you might smell today. Commander Yu was leading him by the hand through the sorghum, where three hundred fellow villagers, heads pillowed on their arms, were strewn across the ground, their fresh blood turning the black earth into a sticky muck that made walking slow and difficult. The smell took their breath away. A pack of corpse-eating dogs sat in the field staring at Father and Commander Yu with glinting eyes. Commander Yu drew his pistol and fired—a pair of eyes was extinguished. Another shot, another pair of eyes gone. The howling dogs scattered, then sat on their haunches once they were out of range, setting up a deafening chorus of angry barks as they gazed greedily, longingly at the corpses. The odor grew stronger.

“Jap dogs!” Commander Yu screamed. “Jap sons of bitches!” He emptied his pistol, scattering the dogs without a trace. “Let’s go, son,” he said. The two of them, one old and one young, threaded their way through the sorghum field, guided by the moon’s rays. The odor saturating the field drenched Father’s soul and would be his constant companion during the cruel months and years ahead.

Sorghum stems and leaves sizzled fiercely in the mist. The Black Water River, which flowed slowly through the swampy lowland, sang in the spreading mist, now loud, now soft, now far, now near. As they caught up with the troops, Father heard the tramping of feet and some coarse breathing fore and aft. The butt of a rifle noisily bumped someone else’s. A foot crushed what sounded like a human bone. The man in front of Father coughed loudly. It was a familiar cough, calling to mind large ears that turned red with excitement. Large transparent ears covered with tiny blood vessels were the trademark of Wang Wenyi, a small man whose enlarged head was tucked down between his shoulders.

Father strained and squinted until his gaze bored through the mist: there was Wang Wenyi’s head, jerking with each cough. Father thought back to when Wang was whipped on the parade ground, and how pitiful he had looked. He had just joined up with Commander Yu. Adjutant Ren ordered the recruits: Right face! Wang Wenyi stomped down joyfully, but where he intended to “face” was anyone’s guess. Adjutant Ren smacked him across the backside with his whip, forcing a yelp from between his parted lips: Ouch, mother of my children! The expression on his face could have been a cry, or could have been a laugh. Some kids sprawled atop the wall hooted gleefully.

Now Commander Yu kicked Wang Wenyi in the backside.

“Who said you could cough?”

“Commander Yu . . .” Wang Wenyi stifled a cough. “My throat itches. . . .”

“So what? If you give away our position, it’s your head!”

“Yes, sir,” Wang replied, as another coughing spell erupted.

Father sensed Commander Yu lurching forward to grab Wang Wenyi around the neck with both hands. Wang wheezed and gasped, but the coughing stopped.

Father also sensed Commander Yu’s hands release Wang’s neck; he even sensed the purple welts, like ripe grapes, left behind. Aggrieved gratitude filled Wang’s deep-blue, frightened eyes.

The troops turned quickly into the sorghum, and Father knew instinctively that they were heading southeast. The dirt path was the only direct link between the Black Water River and the village. During the day it had a pale cast; the original black earth, the color of ebony, had been covered by the passage of countless animals: cloven hoofprints of oxen and goats, semicircular hoofprints of mules, horses, and donkeys; dried road apples left by horses, mules, and donkeys; wormy cow chips; and scattered goat pellets like little black beans. Father had taken this path so often that later on, as he suffered in the Japanese cinder pit, its image often flashed before his eyes. He never knew how many sexual comedies my grandma had performed on this dirt path, but I knew. And he never knew that her naked body, pure as glossy white jade, had lain on the black soil beneath the shadows of sorghum stalks, but I knew.

The surrounding mist grew more sluggish once they were in the sorghum field. The stalks screeched in secret resentment when the men and equipment bumped against them, sending large, mournful beads of water splashing to the ground. The water was ice-cold, clear and sparkling, and deliciously refreshing. Father looked up, and a large drop fell into his mouth. As the heavy curtain of mist parted gently, he watched the heads of sorghum stalks bend slowly down. The tough, pliable leaves, weighted down by the dew, sawed at his clothes and face. A breeze set the stalks above him rustling briefly; the gurgling of the Black Water River grew louder.

Father had gone swimming so often in the Black Water River that he seemed born to it. Grandma said that the sight of the river excited him more than the sight of his own mother. At the age of five, he could dive like a duckling, his little pink asshole bobbing above the surface, his feet sticking straight up. He knew that the muddy riverbed was black and shiny, and as spongy as soft tallow, and that the banks were covered with pale-green reeds and plantain the color of goose-down; coiling vines and stiff bone grass hugged the muddy ground, which was crisscrossed with the tracks of skittering crabs.

Autumn winds brought cool air, and wild geese flew through the sky heading south, their formation changing from a straight line one minute to a V the next. When the sorghum turned red, hordes of crabs the size of horse hooves scrambled onto the bank at night to search for food—fresh cow dung and the rotting carcasses of dead animals—among the clumps of river grass.

The sound of the river reminded Father of an autumn night during his childhood, when the foreman of our family business, Arhat Liu, named after Buddhist saints, took him crabbing on the riverbank. On that gray-purple night a golden breeze followed the course of the river. The sapphire-blue sky was deep and boundless, green-tinted stars shone brightly in the sky: the ladle of Ursa Major (signifying death), the basket of Sagittarius (representing life); Octans, the glass well, missing one of its tiles; the anxious Herd Boy (Altair), about to hang himself; the mournful Weaving Girl (Vega), about to drown herself in the river. . . . Uncle Arhat had been overseeing the work of the family distillery for decades, and Father scrambled to keep up with him as he would his own grandfather.

The weak light of the kerosene lamp bored a five-yard hole in the darkness. When water flowed into the halo of light, it was the cordial yellow of an overripe apricot. But cordial for only a fleeting moment, before it flowed on. In the surrounding darkness the water reflected a starry sky. Father and Uncle Arhat, rain capes over their shoulders, sat around the shaded lamp listening to the low gurgling of the river. Every so often they heard the excited screech of a fox calling to its mate in the sorghum fields beside the river. Father and Uncle Arhat sat quietly, listening with rapt respect to the whispered secrets of the land, as the smell of stinking river mud drifted over on the wind. Hordes of crabs attracted by the light skittered toward the lamp, where they formed a shifting, restless cloister. Father was so eager he nearly sprang to his feet, but Uncle Arhat held him by the shoulders.

“Take it easy! Greedy eaters never get the hot gruel.” Holding his excitement in check, Father sat still. The crabs stopped as soon as they entered the ring of lamplight, and lined up head to tail, blotting out the ground. A greenish gl...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherRandom House

- Publication date2003

- ISBN 10 0099451670

- ISBN 13 9780099451679

- BindingPaperback

- LanguageEnglish

- Number of pages384

- Rating

Shipping:

US$ 3.75

Within U.S.A.

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Red Sorghum

Seller: HPB-Ruby, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

paperback. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority!. Seller Inventory # S_412179986

Quantity: 1 available

Red Sorghum

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.6. Seller Inventory # G0099451670I3N00

Quantity: 1 available

Red Sorghum

Seller: HPB-Diamond, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

paperback. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority!. Seller Inventory # S_405610026

Quantity: 1 available

Red Sorghum : A Novel of China

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # GRP9171395

Quantity: 1 available

Red Sorghum

Seller: WeBuyBooks 2, Rossendale, LANCS, United Kingdom

Condition: Very Good. Most items will be dispatched the same or the next working day. A copy that has been read, but is in excellent condition. Pages are intact and not marred by notes or highlighting. The spine remains undamaged. Seller Inventory # wbs7936957459

Quantity: 1 available

Red Sorghum

Seller: medimops, Berlin, Germany

Condition: good. Befriedigend/Good: Durchschnittlich erhaltenes Buch bzw. Schutzumschlag mit Gebrauchsspuren, aber vollständigen Seiten. / Describes the average WORN book or dust jacket that has all the pages present. Seller Inventory # M00099451670-G

Quantity: 3 available

Red sorghum

Seller: Bookbot, Prague, Czech Republic

Condition: Fine. Seller Inventory # 062603a8-e916-41df-a8ad-632779cc82b4

Quantity: 1 available

Red Sorghum (Paperback)

Seller: Grand Eagle Retail, Wilmington, DE, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: new. Paperback. A beautiful and unforgettable classic set in 1930s rural China from the Nobel Prize-winning authorSpanning three generations, this novel of family and myth is told through a series of flashbacks that depict events of staggering horror set against a landscape of gemlike beauty as the Chinese battle both the Japanese invaders and each other in the turbulent 1930s.As the novel opens, a group of villagers, led by Commander Yu, the narrator's grandfather, prepare to attack the advancing Japanese. Yu sends his 14-year-old son back home to get food for his men; but as Yu's wife returns through the sorghum fields with the food, the Japanese start firing and she is killed.Her death becomes the thread that links the past to the present and the narrator moves back and forth recording the war's progress, the fighting between the Chinese warlords and his family's history. Spanning three generations, this novel of family and myth is told through a series of flashbacks that depict events of staggering horror set against a landscape of gemlike beauty as the Chinese 0battle both the Japanese invaders and each other in the turbulent 1930s. Shipping may be from multiple locations in the US or from the UK, depending on stock availability. Seller Inventory # 9780099451679

Quantity: 1 available

Red Sorghum

Seller: Greener Books, London, United Kingdom

Hardcover. Condition: Used; Very Good. **SHIPPED FROM UK** We believe you will be completely satisfied with our quick and reliable service. All orders are dispatched as swiftly as possible! Buy with confidence! Greener Books. Seller Inventory # 4719979

Quantity: 1 available

Red Sorghum

Seller: PBShop.store UK, Fairford, GLOS, United Kingdom

PAP. Condition: New. New Book. Shipped from UK. Established seller since 2000. Seller Inventory # GB-9780099451679

Quantity: 5 available