Synopsis

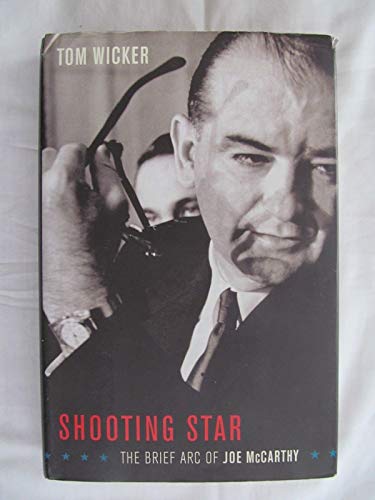

Journalist Tom Wicker examines McCarthy's ambition and record, attempting to discover the motivation for his demagoguery.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Reviews

America's most notorious demagogue emerges as less a fanatic than an opportunist in this lively political biography. Longtime New York Times political writer Wicker, author of well-received studies of Eisenhower and other presidents, notes that the 1950 speech that catapulted McCarthy to fame, in which he claimed to have a list of 205 Communists in the State Department, was a last-minute substitute for a talk on housing policy. When the speech drew unexpected media attention, the obscure Wisconsin senator deployed his lifelong talent for self-promotion and political theater to keep himself in the headlines. Wicker considers McCarthy, who uncovered not a single Communist, "a latecomer to, and virtually a nonparticipant in the real anticommunist wars" that continued after his downfall. Wicker situates McCarthyism within the prevailing climate of Cold War tensions, anticommunist paranoia and conservative animus against organized labor and New Deal liberalism. Against this backdrop McCarthy appears a human figure, undone by his own bullying manner, alcoholism and hubris in antagonizing powerful foes in the Senate and Eisenhower administration. Although Wicker's take on McCarthy isn't groundbreaking, he combines insightful political history with a deft character study to craft a wonderful introduction to this crucial American figure. (Mar.)

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

From February 1950 to December 1954, the nondescript, content-free Republican junior senator from Wisconsin, Joseph R. McCarthy (1908-57), galvanized the nation with charges that there were Communists in the State Department and, of all places, the army. The press seldom asked McCarthy for particulars, which seems incredible, but the context Wicker sketches is that of great trust in those who ran for elective office and great fear of communism, whose genuine minions Congressman Richard Nixon and others had already shockingly exposed. McCarthy never nailed a single commie, and he fatally overreached in attacking the army, whose courtroom-sharpie counsel, Joseph N. Welch, shot him down as millions watched during the first nationally televised government proceedings. Welch and the army were abetted, as Wicker shows, by important Republicans, including President Eisenhower, as well as by McCarthy's drinking (he died of alcohol-related conditions) and the repulsiveness of such henchmen as Roy Cohn. From henceforward, consider Wicker's efficient, modest, eminently readable brief everyone's first book on the man who gave us McCarthyism. Ray Olson

Copyright © American Library Association. All rights reserved

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

However interminable those years seemed to me, they were in fact relatively few. Joe McCarthy first became visible to the nation on February 9, 1950, when he delivered a Lincoln Day address to local Republicans in Wheeling, West Virginia. That night, according to various and differing accounts, he declared something like “I have here in my hand a list of 205” members of the Communist Party, “still working and shaping policy in the State Department.”

Just less than five years after that speech, following December 2, 1954, McCarthy virtually disappeared. That day the United States Senate—his power base, his political bunker—voted by sixty-seven to twenty-two to “condemn” him for conduct bringing that body into disrepute. Every Democratic senator except John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts, who was in the hospital, voted for what most senators believed to be a resolution of “censure.”* Twenty-two Republicans—members of the party that had done the most to advance and sustain McCarthy—joined the Democrats, some with relief at the end of a political reign they had considered an ordeal.

Even this climactic moment of defeat brought out McCarthy’s peculiar jauntiness:

“It wasn’t,” he told the reporters who had done so much to spread his fame and power, “exactly a vote of confidence.”

He then added with characteristic bravado and exaggeration:

“I’m happy to have this circus over, so I can get back to the real work of digging out communism, corruption, and crime.”

He never did. Strictly speaking, he never had.

McCarthy’s Wheeling speech in February 1950 is one of the most consequential in ntry-region w:st="on"U.S. history without a recorded or an agreed-upon text, nor was it connected to a noteworthy cause such as an inaugural or a commemoration; instead, it resulted from ordinary political bureaucracy. The Republican Party’s speaker’s bureau had routinely assigned McCarthy, then a little-known one-term senator regarded unfavorably by many of his colleagues, to a five-speech Lincoln Day tour that began in Wheeling and ended in Huron, South Dakota—hardly major political forums. Party elders had no idea what he would say, other than the usual political balderdash; neither, probably, did McCarthy, who arrived in Wheeling with two rough drafts—one concerning housing, then his Senate “specialty,” the other on communists in government.

The origins of the second speech are undetermined but not totally obscure. As early as his winning Senate campaign against Democrat Howard McMurray in 1946,* McCarthy had used “Red scare” rhetoric, enough so that McMurray complained in one of the campaign debates that his loyalty had never before been challenged by a “responsible citizen . . . [T]his statement is a little below the belt.” That did not deter McCarthy from repeating the accusation and others like it.1

In later years McCarthy gave different reasons for his ultimate turn, after four relatively undistinguished years in the Senate, to all-out Red hunting. On various occasions McCarthy cited a warning from Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal about the dangers of communist infiltration; an investigation of fur imports that uncovered the Soviet Union’s use of its fur trade to advance its espionage; an invitation from an unspecified FBI team to take on the communist problem; the defeat of Leland Olds for reappointment as chairman of the Federal Power Commission after hearings in which senators led by Lyndon B. Johnson decided that Olds was maybe a Red or anyway at least too radical; and the exposure of Alger Hiss and his conviction for perjury on January 21, 1950, just before the Wheeling speech.

None of these events is convincing as a real turning point. Forrestal, for example, was dead when McCarthy’s claim appeared, so that it could not be checked with him, and the fur-import yarn is implausible on its face. More believable is a story first published by the late columnist Drew Pearson about a dinner in January 1950 at Washington’s once-popular, now-defunct Colony Restaurant. That night, Pearson reported, McCarthy entertained Father Edmund Walsh, dean of the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service; William A. Roberts, a Washington attorney who represented Pearson; and Charles Kraus, a fervently anticommunist speechwriter for McCarthy. The senator sought advice, Pearson wrote, on building a record for his reelection campaign in 1952; Father Walsh suggested “communism as an issue,” and McCarthy supposedly leaped at the idea.

This tale has been widely accepted, but it, too, should be taken with a dash of skepticism. In the first place, “communism as an issue” had been a Republican staple for years. (The Republican vice-presidential candidate in 1944, Senator John W. Bricker of Ohio, had tried even that early on to make the point: “First the New Deal took over the Democratic party and destroyed its very foundation; now these communist forces have taken over the New Deal and will destroy the very foundations of the Republic.”) Red-baiting was a Republican tactic in which a leader as respected as Robert A. Taft of Ohio sometimes indulged. In the second place, a senator who had used alleged communism against Howard McMurray in 1946 and who was well aware of communism as a national political issue could hardly have been knocked off his horse, like Saul on the road to Damascus, by a suggestion that he retake a well-trodden path.

Even before the Colony dinner, McCarthy had blasted Secretary of State Dean Acheson for refusing “to turn his back” on Alger Hiss. In November 1949, moreover, McCarthy had furiously attacked one of his most bitter home-state enemies, the Madison Capital Times, in an eleven-page mimeographed statement claiming that the newspaper followed the communist line, aping the Daily Worker in its news treatment; that its city editor was known to its publisher as a communist; and that the Capital Times’ anti-McCarthy investigations were communist inspired. McCarthy raised the question whether the Capital Times might be “the Red mouthpiece for the Communist party in Wisconsin?” He also called for an economic boycott of the paper (an action that never materialized). The statement was franked and mailed throughout Wisconsin.

The author of such an attack needed no suggestion from Father Walsh (who later repudiated McCarthy’s extreme brand of anticommunism) to realize that “communism as an issue” was headline stuff. The assault on the Capital Times* had already brought McCarthy more publicity in Wisconsin than any of his activities in the Senate.

McCarthy’s Wheeling speech, far from being a sudden inspiration, reflected the senator’s late debut in what by 1950 had become a full-dress Republican campaign against the communists, “fellow travelers, Reds, and pinks” that party spokesmen insisted (with good reason) had infiltrated (to an extent they exaggerated) the Democratic Party and the Roosevelt and Truman administrations. As far as has been verified over the years, McCarthy had nothing new or original to add to the campaign—save, crucially, the drama, hyperbole, and audacity of which he quickly showed himself a master.

In the rough draft McCarthy handed on February 9 to Wheeling reporters (who, at his jovial request, had counseled him to make the anticommunist rather than the housing speech), he openly plagiarized a newly famous predecessor in the Red-hunting field, Representative Richard M. Nixon of California:

Nixon (to the House of Representatives, January 26, 1950): The great lesson which should be learned from the Alger Hiss case is that we are not just dealing with espionage agents who get 30 pieces of silver to obtain the blueprints of a new weapon . . . but this is a far more sinister type of activity, because it permits the enemy to guide and shape our policy.

McCarthy (in the rough draft of his Wheeling speech on February 9, 1950): One thing to remember in discussing the Communists in our government is that we are not dealing with spies who get 30 pieces of silver to steal the blueprint of a new weapon. We are dealing with a far more sinister type of activity because it permits the enemy to guide and shape our policy.

The senator also included a three-paragraph article written by the Chicago Tribune’s Willard Edwards, a journalistic pioneer in anticommunist “investigations.” Not only was anticommunism old stuff; Joe McCarthy was parroting a line frequently laid down by Nixon, reporters such as Edwards and George Sokolsky, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), numerous Republican oligarchs, and even some conservative Democrats (notably, Pat McCarran of Nevada).

The “real news” at Wheeling, if any, was in the specificity of McCarthy’s numbers, as they were widely reported, and in the drama of his presentation—“I hold here in my hand” an incriminating document, evidence—after all the generalized perfidy his party had assigned to the Democrats and their New Deal and Fair Deal. At the outset Joe McCarthy displayed his gift for drama. He surely recognized then, too, the ease with which distortion, confidently expressed, could be made to seem fact.

Copyright © 2006 by Thomas Wicker

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Requests for permission to make copies of any part

of the work should be mailed to the following address: Permissions Department, Harcourt, Inc.,

6277 Sea Harbor Drive, Orlando, Florida 32887-6777.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

Other Popular Editions of the Same Title

Search results for Shooting Star: The Brief Arc of Joe Mccarthy

Shooting Star

Seller: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00086151813

Shooting Star: The Brief Arc of Joe McCarthy

Seller: More Than Words, Waltham, MA, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. . Good. All orders guaranteed and ship within 24 hours. Before placing your order for please contact us for confirmation on the book's binding. Check out our other listings to add to your order for discounted shipping. Seller Inventory # WAL-M-4a-001874

Shooting Star: The Brief Arc of Joe McCarthy

Seller: HPB-Emerald, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Seller Inventory # S_446301511

Shooting Star: The Brief Arc of Joe Mccarthy

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G015101082XI4N10

Shooting Star: The Brief Arc of Joe Mccarthy

Seller: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G015101082XI4N10

Shooting Star : The Brief Arc of Joe Mccarthy

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 3979006-6

Shooting Star : The Brief Arc of Joe Mccarthy

Seller: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Seller Inventory # 306205-75

Shooting Star : The Brief Arc of Joe Mccarthy

Seller: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 3979006-6

Shooting Star : The Brief Arc of Joe Mccarthy

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 8612281-6

Shooting Star : The Brief Arc of Joe Mccarthy

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Seller Inventory # 8997577-6