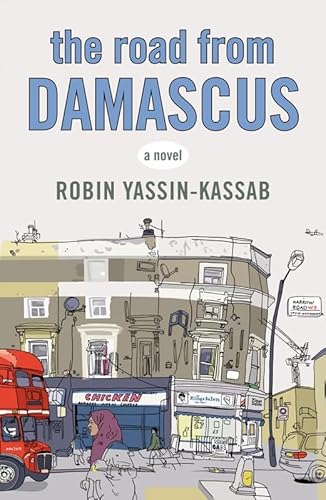

Items related to The Road from Damascus

Furious with Muntaha, he finds himself embarking on a spontaneous quest for meaning and fulfillment, but all too soon his search spirals into a hedonistic rampage and threatens to destroy everything that he has . . .

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

The Other Path

Uncle Mazen drove Sami into the city as far as the parliamentbuilding, then shrugged and peered out through the windscreen.‘The car wouldn’t make it up there,’ he said, pointing an ear at themountainside. ‘There aren’t any roads anyway. Just steps. Perhapsyou can walk.’

Sami disembarked and straightened on the pavement. A manof average height, somewhat hunched, with a pale complexion, asensitive, moving face, black eyes flashing with an intensity calledbeautiful by those that love him, and thick and curling hair, alsoblack, grown longer than in his youth to distract from climbingbaldness. Still handsome. But a body aging quickly, increasinglyswell-bellied. Thirty-one years old.

And feeling foreign now, unsteady in the heat, among balloonsalesmen, bootblacks, cassette stalls, exhaust fumes. Sami searchingfor breath in the smothered heart of Damascus, home of his ancestors,the former city of streams and orchards the Prophet hadrefused to enter, not wishing to commit the sin of believing himselfin Paradise. But Sami, unconcerned with Paradise, for better orworse, had entered. Damascus was supposed to offer him answers.

He’d been here for a month, in order to (he listed): reconnectwith his roots; remember who he was; find an idea. And the touriststuff too: to bathe in the wellsprings of the original city, the oldestcontinuously inhabited city on earth. A city that had briefly ruledthe world. Where jasmine and honeyed tobacco scented the eveningair. Where Ibn Arabi wrote his last mystical poetry, where NizarQabbani wrote ‘Bread, Hashish and Moon’.

Years ago Sami thought he would write a doctoral thesis onQabbani. Not thought; assumed. It had seemed inevitable, and ithad never happened. Nothing remained of whatever that idea hadbeen. So he was here to find a new idea, gather material – and thenreturn home, write the thesis, become Dr Sami Traifi. As a properacademic, like his father before him, he’d be able to get it all backon course, his place in the world, his marriage, his mother. So hebelieved. A new idea, a turned leaf. It was time, it was perhaps hislast chance, to leave childish things behind.

In front of him the mountain was sandy red and imposing,shiny with whitewashed shacks and satellite dishes. One of thosebuildings, his maternal aunt Fadya’s house, was his destination. Tohis right as he walked there was the rubble of destroyed fourstoreyOttoman homes: tangled wood and plaster and a back wallstill intact with a mosaic of dead rooms printed on its surface.

You could make out the hitherto private squares of paint, entireinescapable universes for their inhabitants, now brought borderlessinto promiscuous intimacy. On one patch there was somereligious calligraphy. On another, what looked like family photographs.Though the demolition was some days old, white dustmotes swirled thickly. History refusing gravity.

Just about all the women Sami could see were wearing the hijab,many more than on his last visit. He didn’t like it. He didn’t likesupernaturalism, nor backwardness in general. And in this countrya return to religion meant a return to sect. It was just under thesurface, just under the smiling face of this hospitable people, thesecret loathing of the other path. They don’t respect each other,Sami thought. They fear the strong and despise the weak. Thiscacophonous country: each individual playing from his own score,ignoring the others. But it was his country too. His father’s country.

Struggling upwards against the descending swell of well-wrappedladies, across Corncob Square with its melancholic bronze president,Sami imagined roadblocks, men with armbands and guns andarmed identities. That’s what it could be like, very easily. Thewrong identity would end you at the intersection. Dead for wearinga cross. Dead for wearing a hijab. Dead for Ali’s sword swingingfrom your car mirror. It had nearly happened in the eighties whenthe Muslim Brothers took over the city of Hama, and the governmenthad stopped it, rightly. In the face of the Brothers’ fanaticismthe government stood unwaveringly firm. Sami’s father, Mustafa,safe in London, had explained it to him. Beards disappeared. Surelya good thing. The headscarf tide was reversed. Hair breathed freely.What rational person would disagree with that?

And as he bobbed past coffee merchants, past careening taxis andminibuses, past a line of shawarma furnaces flaring the afternooninto more surreal heat, he asked himself what his father wouldthink if he could see this determinedly Muslim population, hairyand hijabbed not twenty years after the Hama events. What wouldhis father say? It would represent the very end of the world he’dhoped for.

Back in London, Sami’s own wife was threatening to wear thehijab, which somehow seemed to represent the end of everythingSami had hoped for too.

The road stopped as Uncle Mazen had said it would. Up heremucky children replaced traffic, children loud as traffic, smudgeeyed,tangle-haired, brandishing bleeping plastic weaponry. Therewas the occasional fruitless mulberry tree. The ground was dust,mud where something had spilt. In the winter it would all be mud.Mud and dust alternating, flesh and bone, life and death.He breathed outside Fadya’s wooden door, then swung theknocker. Fadya opened up with a show of surprise and welcomedhim, thanked God for his safety, told him he had illumined herhouse. Her family crowded around him, everybody kissing solemnlyand shaking hands. Fadya welcomed him again. Her hairwas collected under a white scarf which she didn’t remove, despiteher blood relationship to Sami, even after the door was shut. Histwo cousins asked him dutifully for his news, and asked him tomake himself at home, following the formulas. Then they sat onthe floor in front of the TV, their large backs to him, their linedand stubbled faces immobile.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherPenguin Group

- Publication date2008

- ISBN 10 0241144094

- ISBN 13 9780241144091

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages368

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Road from Damascus

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks17446