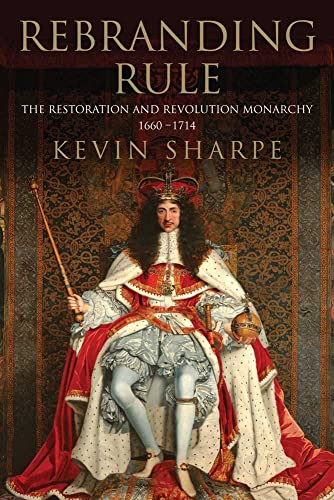

Synopsis

In the climactic part of his three-book series exploring the importance of public image in the Tudor and Stuart monarchies, Kevin Sharpe employs a remarkable interdisciplinary approach that draws on literary studies and art history as well as political, cultural, and social history to show how this preoccupation with public representation met the challenge of dealing with the aftermath of Cromwell's interregnum and Charles II's restoration, and how the irrevocably changed cultural landscape was navigated by the sometimes astute yet equally fallible Stuart monarchs and their successors.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

The late Kevin Sharpe was Leverhulme Research Professor of Renaissance Studies at Queen Mary College, University of London. He was the author of The Personal Rule of Charles 1, Reading Revolutions, Selling the Tudor Monarchy, and Image Wars.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

REBRANDING RULE

THE RESTORATION AND REVOLUTION MONARCHY, 1660–1714

By KEVIN SHARPEYale UNIVERSITY PRESS

All rights reserved.

Contents

| List of Illustrations...................................................... | vii |

| Foreword................................................................... | xii |

| Preface and Acknowledgements............................................... | xvi |

| Introduction: Representing Restored Monarchy............................... | 1 |

| I Re-presenting and Reconstituting Kingship................................ | 9 |

| 1 Rewriting Royalty........................................................ | 11 |

| 2 Redrawing Regality....................................................... | 94 |

| 3 Rituals of Restored Majesty.............................................. | 148 |

| 4 A Changed Culture, Divided Kingdom and Contested Kingship................ | 194 |

| II Confessional Kingship? Representations of James II...................... | 223 |

| Prologue: A King Represented and Misrepresented............................ | 225 |

| 5 A King of Many Words..................................................... | 227 |

| 6 A Popish Face? Images of James II........................................ | 265 |

| 7 Staging Catholic Kingship................................................ | 287 |

| 8 Countering 'Catholic Kingship' and Contesting Revolution................. | 308 |

| III Representing Revolution................................................ | 341 |

| Prologue: An Image Revolution?............................................. | 343 |

| 9 Scripting the Revolution................................................. | 353 |

| 10 Figuring Revolution..................................................... | 409 |

| 11 A King off the Stage.................................................... | 449 |

| 12 Rival Representations................................................... | 481 |

| IV Representing Stuart Queenship........................................... | 507 |

| Prologue: Semper Eadem? Queen Anne......................................... | 509 |

| 13 A Stuart's Words: Queen Anne and the Scripts of Post-Revolution Monarchy................................................................... | 515 |

| 14 Re-Depicting Female Rule: The Image of the Queen........................ | 578 |

| 15 Stuart Rituals: Queen Anne and the Performance of Monarchy.............. | 616 |

| 16 Party Contest and the Queen............................................. | 646 |

| Epilogue................................................................... | 671 |

| Notes...................................................................... | 682 |

| Index...................................................................... | 819 |

CHAPTER 1

Rewriting Royalty

I

In 'A Panegyric Upon His Sacred Majesty's Most Happy Return', the poet ThomasForde wrote in praise of the king:

You Conquered without Arms, your WordsWin hearts, better than others Swords.

Flattering Charles's own sense that he had scripted his own restoration, Fordedepicted the royal word as the victor over violence. In his dedication of hisThe Original and Growth of Printing to Charles in 1664, Richard Atkynsappropriated the scriptural text to make the same point: 'where the word of aking is there is power'. Talking and writing, however, had had no simplerelationship to authority. After the noisy debates of his father's reign,Charles I had preferred a silence from which only the necessities of civil warhad drawn him. After the Babel of civil war, Charles II may have been inclinedto his father's preference: he referred to his own reluctance to write atlength, and it may be that the translation of A Philosophical DiscourseConcerning Speech in 1668 had the English as well as French king in mind whenthe translator referred to 'the prudence you have to be silent'. Charles II didnot choose to repeat himself at length or at large in speech. But recognizing,with Hobbes, that the force of 'the word of a king' (as the Declaration of Bredaput it) was an essential attribute of sovereign authority, Charles regularlyspoke to his parliaments and to his people, and his speeches, throughout hisreign, many of them printed, were directed at the maintenance as well asrepresentation of that authority. Because those speeches were central both toCharles's self-presentation and to how others saw him, I shall analyze themacross the reign, paying attention to how the king adjusted his words toshifting circumstances.

Charles's first major speech to his parliament, to the House of Lords on 27 July1660, concerned a matter of vital import to him and was delivered at a criticalmoment. Royalist and Presbyterian MPs, eager for revenge against their enemies,proved reluctant to pass the Act of Indemnity which Charles regarded asessential to his honour (the upholding of his word given at Breda) and to thestability of a peaceful settlement. After royal promptings eventually pushed thebill through the Commons, Charles addressed the Lords in a speech published tothe nation, with a large royal arms on the title page. It was to the nation asmuch as the house that Charles reaffirmed, lest any began to fear the contrary,that 'I have the same intentions and resolutions now I am here with you which Ihad at Breda.' Thanking the Lords diplomatically for their persecution ofregicides, Charles explained, lest any had read Breda as mere rhetoric, that 'Inever thought of excepting any other'; and he proceeded to justify indemnity asthe best interest of the nation. 'This mercy and indulgence,' he began in thelanguage of virtuous princes, 'is the best way to bring them to a truerepentance.' But widening the argument beyond his own concerns, he continued:'it will make them good subjects to me and good friends and neighbours to youand we have then all our end ... the surest expedient to prevent futuremischief'. The clever use of the first-person plural pronouns, the invocationof peace and unity, but also the reminder of the risk of renewed conflict werecarefully combined to construct the platform of Restoration: restored regalgovernment over all subjects, former Parliamentarians as well as Royalists.Giving his consent to the Act he had secured on 29 August, Charles took theoccasion of a speech to both houses to assert his severity now against any whorefused his clemency, and his love for all others. 'Never king,' he told them,in strains that not for the last time echo Queen Elizabeth's speeches, 'valuedhimself more upon the affections of his people than I do; nor do I know a betterway to make myself sure of your affections than by being just and kind to youall.' In turn, the king felt, he told his auditors, 'so confident of youraffections that I will not move you in anything that ... relates to myself'– though references to debts, the expenses, disbandment money and the PollBill meant that he did not pass entirely over his own needs. Even here,however, in a delightful and masterly close, Charles bemoaned not his own wants:'that which troubles me most,' he told them, 'is to see many of you come to meto Whitehall and to think that you must go somewhere else to seek yourdinner'. It is hardly surprising that the disarming reference, a reminder ofthe fitting bounty of a king but with all the familiarity of friends invited tosupper, prompted a vote of supplies which, for all that it did not fall out soin practice, was reckoned to provide a handsome revenue for the crown.

Interestingly, as the foundation of settlement began to be laid, Charles began adifferent pattern of address to his parliaments: a brief personal speechfollowed by a longer, explanatory gloss by either his Lord Chancellor (and longtime penman) Edward Hyde or subsequent Lord Keepers. Addressing both houses on13 September, Charles, who even in adversity had taken pains over such gesturesof gratitude, expressed his thanks for all the parliament had done for the kingand kingdom, not least in a grant of supply of which, again with a flourishreminiscent of Elizabeth, he promised 'I will not apply one penny of that moneyto my own particular occasions ... till it is evident to me that the public willnot stand in need of it'. Expressing a due concern that they now giveattention to restoring parliament to its 'ancient rules and order', Charleshanded over to Clarendon to speak in his name. Ventriloquizing and reinforcingroyal injunctions to peace and unity, in church as well as state, Clarendonurged his audience to follow the king's example and 'learn this excellent art offorgetfulness' so as not to reanimate divisions. In an astonishingly hedgedclause, he noted 'You know kings are in some sense called Gods' and, like God,the king extended his heart to all. Then, moving to a rather differentrhetoric, the Chancellor, underpinning the king's commitment to the 'publicgood', announced the royal intentions to establish a Council of Trade andanother for the Plantations, very much in the spirit of Protectorialinitiatives. His speech closed with an adage of the king's 'own prescribing':'continue all the ways imaginable for our own happiness and you will make himthe best pleased and the most happy prince in the world'. As the last wordsbefore a recess, one can hardly better them for instilling the 'feel goodfactor' on which Charles knew the stability of his throne yet depended.

Three months later, in December 1660, Charles was to address his firstparliament – strictly speaking a Convention rather than a parliament– for the last time as, having resettled crown and kingdom, it had doneits immediate work and the realm could await a normal assembly duly summoned byroyal writ. The king's tone was fittingly personal and his speech full of first-person pronouns. And as well as a valedictory thanks to one assembly, it wasspoken to future MPs and to the political nation. 'All I have to say,' Charlestold both houses, promising brevity, 'is to give you thanks'; but, once morelike Elizabeth denying any oratorical skills, the king regretted his deficiencyin expressing the thanks he felt: 'ordinary thanks for ordinary civilities areeasily given. But when the heart is as full as mine is', he opened himself tohis auditors, 'it cannot be easy for me to express the sense I have of it.'The king had met them 'with an extraordinary affection and esteem forparliament', but they had enhanced it. To those who might be concerned about aConvention that some might not remember as a true parliament, Charles promisedthem a place in history: 'let us all resolve that this be for ever called "theHealing and Blessed Parliament"'. Announcing that he would soon meet many ofthem again, Charles assured them that they would, even in absence, remain hiscounsel and guide. 'What', he would ask himself at every decision, he assuredthem, 'is a parliament like to think of this action or this council?' Even,briefly without parliament, Charles II announced himself as always a king withparliament.

True to his word, Charles did not waste much time summoning his secondparliament. But as he addressed it on 8 May 1661, the king opened with a half-apology that was also a clever reminder to newly elected MPs of the miracle ofRestoration that had taken place exactly a year ago. Acknowledging that theassembly might have met a week earlier, Charles relished the fact thatparliament had been delayed until the anniversary of his proclamation as kingand noted 'the great affection of the whole kingdom' manifest on that day. 'Idare swear,' he half admonished, half flattered the MPs, 'you are full of thesame spirit.' Personalizing the formality of the occasion and adding intimacyto the rhetoric of unity, Charles noted: 'I think there are not many of you whoare not particularly known to me' and few, he added, about whom he had not heardsuch good testimony as to be confident of all their good endeavours for 'thepeace, plenty and prosperity of the nation'. Turning to business, Charlespresented them with two bills for their confirmation from (the possessivepronoun implicates them fully in the deeds of the last session) 'our lastmeeting'. Above all he again pressed the Act of Indemnity as the 'principalcornerstone' of 'our joint and common security' and made it a test of personalloyalty that they enforce it. The king then closed by confiding in them withnews, indeed admitting his parliament to the most personal of state affairs: hisdeliberations over marriage and his choice of Catherine of Portugal as a bride.This, he made clear, had been no single personal decision; the king would notwithout advice, he observed, 'resolve anything of public importance'. PrivyCouncil concurrence he took as 'some instance of the approbation of Godhimself'. Then, having advertised himself as a king of counsel, Charles satdown to leave his Chancellor to gloss his remarks.

Clarendon, taking up the theme of advice, reminded the houses that Charles hadfrom Breda referred all to parliament, and the Convention ('called by Godhimself') had honoured the trust, as it was for their successors to do. To thenew members, 'the great Physicians of the kingdom', the Chancellor commended theAct of Indemnity and measures to settle the public debts and the king'srevenues. Warning them of seditious preachers who still vented their poisonousdoctrines and of the late rebellion (by Thomas Venner and the Fifth Monarchists)in the city, Clarendon urged them to act to secure the preservation of a nationand a king who, as his marriage deliberations had demonstrated, 'took so greatcare for the good ... of his people'. Emphasizing the considerations of tradethat weighed, along with the advancement of the Protestant religion, on theking's mind, the Chancellor again stressed the lengths Charles had gone to heedadvice and closed reiterating how the king 'hath deserved all your thanks' forthe matter and the manner: the choice of bride and the process of choosing.The royal marriage (even to a Catholicbride) manifested the king's love for his people and his concern for theinterests of the nation.

So commenced a long relationship with a parliament that was not to be dissolvedfor eighteen years – a relationship shaped in large part by the king'swords and responses to them. Though the parliament began as a staunchly loyalbody, the elections had resulted in an aggressively Cavalier Commons that wasmore inclined to pursue vendettas than to follow Charles's preference formoderate courses in church and state. In his speeches Charles then skilfully hadto woo and win the house (which early on set about pursuing more regicides), topersuade MPs to drop proceedings, and to pass a new Act of Oblivion; and, whenhe met with them, he judged well the occasion for thanks and reassurance. 'Letus,' he urged them in rhetoric very familiar to our jaded modern ears, 'lookforward, and not backward.' Only unity and affection for each other wouldsecure the public peace against the disaffected and advance the nation abroad.Presenting settlement and oblivion as the way to future greatness, the kingobtained his bills before the summer adjournment at which he assured membersreturning to their counties that 'you cannot but be very welcome for theservices you have performed here', and adjourned them until November, when 'weshall come happily together again'.

When the houses reconvened in November 1661, Charles was faced with the pressingneed to plead his own case, while not appearing to pursue his self-interest. Hisopening congratulations to a parliament, now fully constituted of Lordsspiritual as well as temporal and Commons, set the mood. Then adeptly Charlesdenied any necessity to ask anything for himself when he knew that, left tothemselves, members would do all for his good. No, he insisted, it was not hisparticular need that brought him before them with a plea, but 'as I am concernedin the public'. The revenue of the crown, he told them, was 'for the interest,honour and security of the nation' – for the fleet and its provisions.Subtly alluding perhaps to earlier quarrels that had beset his father's levy ofship money, as well as acknowledging a new world in which even divine kingshipwas open to scrutiny and suspicion, Charles invited the house to 'thoroughlyexamine whether these necessities be real or imaginary', or whether theconsequence of private royal profligacy rather than public need. In anextraordinary gesture, he offered a 'full inspection into my revenue' that, heclaimed, would dispel any false rumours of extravagance. For all the traditionalrhetoric of the unity of king, parliament and nation, Charles II's speech earlyon in his own first parliament suggests – and helped to construct –a new openness, a new pragmatism, a different style of monarchy that was toemerge alongside the old discourses and symbols of state. In parliament, whilerhetorically denying the need to do so, Charles understood that, more than hispredecessors, he must argue and justify his case.

The address set the tone for subsequent speeches to the house: expressions ofmutual affection, a recognition of their care, and pleas for supply andexpedition, 'to advance the public service', when the Commons got bogged downwith private bills. As weeks and months passed, on 10 January 1662 Charlesreminded new MPs of the 'miserable effects' caused by the necessities of thecrown in the recent past, and warned them of a still-present republican threatthat only a strong monarchy could quell. Turning to their own concerns anddiscontents, Charles diplomatically thanked them for their solicitude withregard to the church, and – though he sensibly did not name it – hispreferred policy of toleration. In a newly familiar vein, the king light-heartedlyindulged a personal reference: 'I have the worst luck in the world,'he quipped, 'if after all the reproaches of being a papist whilst I was abroad,I am suspected of being a Presbyterian now I am come home'. Charles assertedhis devotion to the Book of Common Prayer and to uniformity which he hadcommended to the Lords; what he yet favoured, he told them by way ofqualification, was 'prudence and discretion and the absence of all passion'.Despatching the MPs, Charles closed with a reminder of the impending arrival ofhis betrothed and the major business of the spring, his marriage.

(Continues...)

Excerpted from REBRANDING RULE by KEVIN SHARPE. Copyright © 2013 Estate of Kevin Sharpe. Excerpted by permission of Yale UNIVERSITY PRESS.

All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Excerpts are provided by Dial-A-Book Inc. solely for the personal use of visitors to this web site.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

Search results for Rebranding Rule: The Restoration and Revolution Monarchy,...

Rebranding Rule: The Restoration and Revolution Monarchy, 1660-1714

Seller: Midtown Scholar Bookstore, Harrisburg, PA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Very Good - Crisp, clean, unread book with some shelfwear/edgewear, may have a remainder mark - NICE Oversized. Seller Inventory # M0300162014Z2

Rebranding Rule: The Restoration and Revolution Monarchy, 1660-1714

Seller: Midtown Scholar Bookstore, Harrisburg, PA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. Good - Bumped and creased book with tears to the extremities, but not affecting the text block, may have remainder mark or previous owner's name - GOOD Oversized. Seller Inventory # M0300162014Z3

Rebranding Rule: The Restoration and Revolution Monarchy, 1660-1714

Seller: Sequitur Books, Boonsboro, MD, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: New. Hardcover and dust jacket. Good binding and cover. Clean, unmarked pages. Dust jacket in protective mylar cover. This is an oversized or heavy book, which requires additional postage for international delivery outside the US. Seller Inventory # 2501140038

Rebranding Rule: the Restoration and Revolution Monarchy, 1660-1714

Seller: Daedalus Books, Portland, OR, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Near Fine. Dust Jacket Condition: Near Fine. First Edition; First Printing. A nice, bright copy. ; B&W Photographs; 9.3 X 6.6 X 2.9 inches; 849 pages. Seller Inventory # 286817

Rebranding Rule: The Restoration and Revolution Monarchy, 1660-1714

Seller: St Philip's Books, P.B.F.A., B.A., Oxford, United Kingdom

Hardcover. Condition: Fine. Dust Jacket Condition: Fine. 1st edn. ~No ownership marks. Dustwrapper unfaded and unclipped. ~Robust packaging. Overseas tracking available on request. Used books are exempt from USA tariffs. Size: xxii, 849pp. Seller Inventory # RR6011

Buy Used

Ships from United Kingdom to U.S.A.

Quantity: 1 available

Rebranding Rule - The Restoration and Revolution Monarchy, 1660-1714

Seller: PBShop.store US, Wood Dale, IL, U.S.A.

HRD. Condition: New. New Book. Shipped from UK. Established seller since 2000. Seller Inventory # WY-9780300162011

Rebranding Rule - The Restoration and Revolution Monarchy, 1660-1714

Seller: PBShop.store UK, Fairford, GLOS, United Kingdom

HRD. Condition: New. New Book. Shipped from UK. Established seller since 2000. Seller Inventory # WY-9780300162011

Buy New

Ships from United Kingdom to U.S.A.

Quantity: 15 available

Rebranding Rule

Seller: Majestic Books, Hounslow, United Kingdom

Condition: New. pp. 872 90 Illus. Seller Inventory # 55100211

Buy New

Ships from United Kingdom to U.S.A.

Quantity: 3 available

Rebranding Rule: The Restoration and Revolution Monarchy, 1660-1714

Seller: Chiron Media, Wallingford, United Kingdom

Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 6666-WLY-9780300162011

Buy New

Ships from United Kingdom to U.S.A.

Quantity: 17 available

Rebranding Rule

Seller: Rarewaves.com USA, London, LONDO, United Kingdom

Hardback. Condition: New. In the climactic part of his three-book series exploring the importance of public image in the Tudor and Stuart monarchies, Kevin Sharpe employs a remarkable interdisciplinary approach that draws on literary studies and art history as well as political, cultural, and social history to show how this preoccupation with public representation met the challenge of dealing with the aftermath of Cromwell's interregnum and Charles II's restoration, and how the irrevocably changed cultural landscape was navigated by the sometimes astute yet equally fallible Stuart monarchs and their successors. Seller Inventory # LU-9780300162011

Buy New

Ships from United Kingdom to U.S.A.

Quantity: 9 available