Items related to Our Man in Charleston: Britain's Secret Agent in...

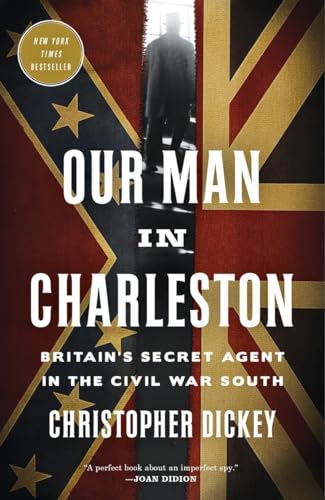

Between the Confederacy and recognition by Great Britain stood one unlikely Englishman who hated the slave trade. His actions helped determine the fate of a nation.

When Robert Bunch arrived in Charleston to take up the post of British consul in 1853, he was young and full of ambition, but even he couldn’t have imagined the incredible role he would play in the history-making events to unfold. In an age when diplomats often were spies, Bunch’s job included sending intelligence back to the British government in London. Yet as the United States threatened to erupt into Civil War, Bunch found himself plunged into a double life, settling into an amiable routine with his slavery-loving neighbors on the one hand, while working furiously to thwart their plans to achieve a new Confederacy.

As secession and war approached, the Southern states found themselves in an impossible position. They knew that recognition from Great Britain would be essential to the survival of the Confederacy, and also that such recognition was likely to be withheld if the South reopened the Atlantic slave trade. But as Bunch meticulously noted from his perch in Charleston, secession’s red-hot epicenter, that trade was growing. And as Southern leaders continued to dissemble publicly about their intentions, Bunch sent dispatch after secret dispatch back to the Foreign Office warning of the truth—that economic survival would force the South to import slaves from Africa in massive numbers. When the gears of war finally began to turn, and Bunch was pressed into service on an actual spy mission to make contact with the Confederate government, he found himself in the middle of a fight between the Union and Britain that threatened, in the boast of Secretary of State William Seward, to “wrap the world in flames.”

In this masterfully told story, Christopher Dickey introduces Consul Bunch as a key figure in the pitched battle between those who wished to reopen the floodgates of bondage and misery, and those who wished to dam the tide forever. Featuring a remarkable cast of diplomats, journalists, senators, and spies, Our Man in Charleston captures the intricate, intense relationship between great powers on the brink of war.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Award-winning author CHRISTOPHER DICKEY, the foreign editor of The Daily Beast, is based in France. Previously he was the Paris bureau chief and Middle East editor for Newsweek. He served as Cairo bureau chief for the Washington Post and, before that, as the paper's Central America bureau chief. His books include the acclaimed memoir Summer of Deliverance as well as Securing the City, Expats, With the Contras, and two novels about espionage and terrorism.

The journey from Washington, D.C., to Charleston, South Carolina, took two days and two nights in 1853, which gave a traveler a lot of time to think, especially if he was with a new bride and about to embark on an ambitious new assignment in a place and culture and clime that he thought both he and she were sure to hate.

Robert Bunch was thirty-two years old and about to assume the office of British consul in Charleston. He was not an imposing figure. He had sharp blue eyes and was slight of build; his hair was thinning; he dressed with little flair and comported himself in a manner, as William Howard Russell noted years later, that was "thoroughly British." Bunch was energetic and perceptive, with an acid wit when he was among those few people he genuinely took into his confidence, and his persistence could be annoying. An ambitious man, he had spent years maneuvering to get posted as Her Majesty's consul somewhere, and while serving as the deputy consul in New York City he'd played every angle he could. Finally the Foreign Office put him in Philadelphia, a major American city and a prime assignment, but he'd been there only a matter of weeks when suddenly London decided he should trade places with the consul in Charleston, who'd created an ugly international incident about the treatment of Negro British sailors.

Bunch had to judge whether South Carolina was a post that would bring him advancement or stall his career like a sinking boat in a fetid swamp. A consul's job could be like that of an exalted clerk, or it could be the work of a diplomat. Some of Her Majesty's consuls, over the years, had exercised great authority in other parts of the world, even calling in British warships to enforce British interests. What Bunch wanted was to use his new post as a bridge to a full-fledged position in the diplomatic service as a chargé d'affaires or, in his boldest dreams, a minister to a foreign government. In Charleston, the array of issues he'd have to deal with, which centered on the problem of slavery, were ones important to London politically and economically--certainly more important than the commercial details he'd been cataloguing in Pennsylvania. And his predecessor in Charleston had made a glorious mess of things. Could Bunch do better? He was tempted to think that he could hardly do worse.

Bunch's predecessor had not even been seen in Charleston for more than a year. George Buckley Mathew had lingered in London most of that time, holed up in the Carlton Club on St. James's Street, because, as he said, his performance of his "duties" in South Carolina had rendered his presence there, "in a social sense, very unpleasant." Many thought it was his performance, period, that had been the problem. Mathew's high opinion of himself was notorious. Contempt for the American "mobocracy" was common currency in the British Foreign Service, and Mathew did little to conceal his disdain. Soon after his appointment to Charleston in 1850, he took copious quantities of strong Madeira wine to the state capital, Columbia, and set about plying the legislators. It was a friendly enough gesture, but behind their backs he called the lawmakers "small fry" and suggested he knew "better than they did what was good for them." The Carolinians, proud to a fault in any case, understood soon enough what his real feelings were. Instead of winning their approval, he earned their opprobrium.

Yet Mathew was of a class, and with the connections, that gave him, in British society, vast leeway to fail. He was as much a soldier, a landowner, and a politician as he was a diplomat. (With unconvincing self-deprecation he called himself "a poor Peelite and West Indian proprietor.") He had been a member of Parliament and governor of the Bahama Islands. He also had the particular backing of the long-serving Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, whose passionate opposition to slavery was characterized by moral righteousness, political wiliness, and commercial ruthlessness. Palmerston believed in the use of Britain's great military power whenever and wherever its flag or its citizens were challenged. And Palmerston had appointed Mathew to Charleston to make a muscular defense of the Crown's interests.

Bunch hated Mathew. He detested his arrogance and his inflated reputation. But at that moment, as he traveled to Charleston to try to set things straight, he himself could not be sure of consistent backing from London. He had no military rank, no political title, no lands to speak of. When Mathew was consul in South Carolina--when he was actually on the ground there--his overbearing personality made him offensive to the provincials, and Bunch certainly could present himself as someone different, younger, more self-effacing, more subtle, more visibly appreciative of the Carolinians' concerns. All that was certain. But there really was no guarantee that Bunch could solve the problems that Her Majesty's government wanted solved. And failure, in his case, unlike Mathew's, could mean the termination of his hopes for a career in diplomacy.

The specific issue Mathew was supposed to have dealt with, and that Bunch was inheriting, was the treatment of black British seamen. Most of them were from the British West Indies, and all of them were free men. Under the laws of South Carolina, if they went ashore or even came into Charleston Harbor, they would be thrown into jail until their ship was about to sail and only then put back on board--that is, if they were lucky. The ostensible reason for all this was the fear that West Indian blacks might have a subversive influence on the local slaves and even incite them to insurrection. White Southerners lived in constant dread that if their servants and laborers were exposed to blacks who had tasted real freedom, they might be inspired to rise up and kill their masters. The fear had grown incalculably worse after the slave uprisings and massacres in French Saint-Domingue, or Haiti, in the late eighteenth century. Then the British had freed all their slaves in the West Indies in the 1830s. The infection of freedom was feared to be contagious. Talk of emancipation was treated in the American South as a kind of disease that might arrive aboard ships. Liberated blacks were seen as carriers of an insurrectionary plague that must be quarantined.

The first Negro Seamen Act was passed in 1822, after a planned slave uprising in Charleston was said to have been inspired and organized by a free person of color originally from the West Indies named Denmark Vesey, who had lived and worked and preached in South Carolina for years. The law was aimed at transient sailors from the North or from other countries. Under the act's provisions, county sheriffs would be obliged to arrest all black seamen, regardless of nationality, until their ships were ready to leave harbor. The captain of the ship would have to pay for the cost of the incarceration, and if he refused to do so, he could be fined and imprisoned, while the black sailors aboard his vessel would be "deemed and taken as absolute slaves, and sold." There was also the risk that the jailed British seamen would be kidnapped by God knows who and sold into slavery God knows where. They were, after all, valuable livestock in the slave markets of the South.

Thirty years later the law was still on the books in South Carolina, it had been replicated in other Southern states, and the issue was a major annoyance for the British. Every time they made port calls in the South, the blacks aboard would be dragged off and thrown into prison, or worse, and the indignation in London grew steadily more intense. When a black stewardess from a British ship was jailed and nearly raped in Alabama, Lord Palmerston denounced the policy as one that had "no parallel in the conduct of any other civilized country."

The feeble Federal government in Washington did not want to intervene for fear that any effort to regulate the treatment of blacks in Southern states, whether they were free or slave, might break the Union apart. So Palmerston gave increasing power to the consuls to deal directly with the state governments. Some took a tactful, fairly conciliatory approach, and with adequate success, as the laws were changed or ceased to be enforced. But in South Carolina, where the people already had a hair-trigger reflex on any slave-related issue, Mathew, the old military man, repeatedly struck a pose of moral indignation. He wrote formal letters to the governor of South Carolina that were leaked to the press and managed not only to offend local sensibilities but also to outrage Northern commentators who wondered why someone in Her Majesty's service would be dealing with South Carolina as if it were a sovereign state. As Mathew found himself ostracized in Charleston, criticized in Washington, and questioned in London about the path he was pursuing, he only grew more truculent. He started threatening South Carolina politicians with unspecified consequences if they didn't come around on the Negro seamen issue.

In 1850, as it had done before and would afterward, South Carolina was thinking about pulling out of the Union. Mathew seemed to suggest that if Britain did not get what it wanted, it would never back South Carolina's drive toward secession, but, then again, he did not guarantee it would back secession in any case. Eventually everything he asked for in the state, no matter how reasonable, and everything he demanded, no matter how dire the threats that surrounded it, was deemed utterly unacceptable by almost every person of influence in South Carolina. Finally in 1852, after consultations in Washington, Mathew vowed to take the cases of two jailed black British seamen to the United States Supreme Court. This he did against the advice of the Charleston lawyer he'd retained, the redoubtable James L. Petigru, who was one of the most respected attorneys and one of the strongest voices for moderation in a state where indignant rage was as common as yellow fever. Petigru warned Mathew that Carolinians would ignore the Supreme Court if they didn't like its ruling, and if that helped lead to secession, many of them would think that was so much the better. In the meantime Mathew found himself snubbed wherever he turned. His dispatches to London conveyed a growing sense of futility.

By the time the court cases were decided, Mathew had abandoned his post. He left Charleston in October 1852, settled into the Carlton Club, a fifteen-minute walk from the Foreign Office on Downing Street, and set about negotiating a new position for himself. But his patron, Lord Palmerston, was no longer Foreign Secretary, and the Earl of Clarendon, who took over in February 1853, had little use for Mathew's excuses. In a sure sign of displeasure, Foreign Office clerks started questioning the consul's expense accounts. And when Mathew finally did decide to return to the United States in June that year--not to Charleston but to New York and eventually to the consulate in Philadelphia--the Foreign Office refused to pay for his passage.

Intentionally or not, Mathew's tone-deaf handling of what was referred to in correspondence as "the coloured seamen issue" threw into relief the qualities that a man might need to survive as British consul in a place as prone to outrage as Charleston. Any official who hoped to achieve Her Majesty's ends there must be capable of a more delicate touch, with more savoir faire, more social awareness. To live among the slave-owning planters and make inroads into their society, charming them while never forgetting the core interests of the Crown, required a man with a special background and demeanor, and Robert Bayley Bunch had a very unusual pedigree.

Although Bunch seemed on first acquaintance to be thoroughly British, he was, in fact, an Englishman of the Americas, including South America. Bunch's mother was a New Yorker related on her father's side to such notable figures as Elizabeth Ann Bayley Seton (eventually named the first American saint), and on her mother's side to the Barclays, with a family tree that included Tories who had spied for the British during the American Revolution and the War of 1812, then served as the Crown's consuls general in New York City up into the 1850s. These were very well-connected clans deeply embedded in, and intermarried with, the other elite families of New York City, including the Van Cortlandts and the Roosevelts, and they kept very close ties with one another. Indeed, Emma Craig, Bunch's new wife, was also his first cousin: the daughter of his American mother's sister.

Bunch's father, on the other hand, was an English gunrunner, originally based in Jamaica and the Bahamas, who helped finance and arm the great Latin American revolutionary Simon Bolivar. El Libertador eventually gave the elder Bunch a large tract of land outside of Bogota, and Bunch brought in British experts to help him set up the first ironworks in what was then called Nueva Granada.

Robert Bayley Bunch and his younger sister and brother were all born in the United States in the 1820s and baptized at the very heart of the American establishment, in New York City's Trinity Church, where Wall Street meets Broadway. But their mother died when they were still small children, so they grew up in the homes of relatives and, eventually, on the Colombian estate, or finca, that belonged to their father. Bunch probably spent some time in school in Britain and later said that he went to Oxford, but he does not appear in the university's lists of graduates.

His first Foreign Service-related jobs were in Colombia, as an unpaid secretary working for the British envoy in Bogota, then in Peru, before finally heading to New York in 1848 aboard the packet steamer Trent to work as the vice consul under Anthony Barclay, one of his cousins. The young deputy's cosmopolitan roots soon recommended him to Lord Henry Bulwer, the British minister to Washington, who entrusted him with several delicate assignments far removed from consular routine. New York City, with its enormous population of immigrants, exiles, and visiting notables was a center of perpetual intrigue, and Bunch learned about those groups and conspiracies that might affect the Crown's interests. He tracked the activities of adventurers plotting to invade Cuba. He appears to have planted stories in the New York press opposing efforts by the tycoon Cornelius Vanderbilt to monopolize the lucrative passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific across Nicaragua. He followed the activities of revolutionaries who fought to unite Italy alongside Giuseppe Garibaldi, who was living on Staten Island at the time. Bunch also watched shipyards where Britain's enemies might have naval vessels built, and he spied on the construction of the racing yacht America before it sailed against the Royal Yacht Club in the fateful competition off the Isle of Wight that became known as the America's Cup race. He was developing his skills as an observer, an ingratiator, a cultivator of useful contacts, and a conversationalist skilled in extracting information. He learned how important it was not only to collect facts, but to calculate the best occasion to use them.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherCrown

- Publication date2016

- ISBN 10 0307887286

- ISBN 13 9780307887283

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages416

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Our Man in Charleston: Britain's Secret Agent in the Civil War South (Paperback or Softback)

Book Description Paperback or Softback. Condition: New. Our Man in Charleston: Britain's Secret Agent in the Civil War South 0.65. Book. Seller Inventory # BBS-9780307887283

Our Man in Charleston: Britain's Secret Agent in the Civil War South

Book Description Condition: New. Brand New! Not Overstocks or Low Quality Book Club Editions! Direct From the Publisher! We're not a giant, faceless warehouse organization! We're a small town bookstore that loves books and loves it's customers! Buy from Lakeside Books!. Seller Inventory # OTF-S-9780307887283

Our Man in Charleston Format: Paperback

Book Description Condition: New. Brand New. Seller Inventory # 0307887286

Our Man in Charleston: Britain's Secret Agent in the Civil War South

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # ABLIING23Feb2215580102289

Our Man in Charleston: Britain's Secret Agent in the Civil War South

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # I-9780307887283

Our Man in Charleston: Britain's Secret Agent in the Civil War South

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # 0307887286

Our Man in Charleston (Paperback)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Paperback. Between the Confederacy and recognition by Great Britain stood one unlikely Englishman who hated the slave trade. His actions helped determine the fate of a nation. When Robert Bunch arrived in Charleston to take up the post of British consul in 1853, he was young and full of ambition, but even he couldnt have imagined the incredible role he would play in the history-making events to unfold. In an age when diplomats often were spies, Bunchs job included sending intelligence back to the British government in London. Yet as the United States threatened to erupt into Civil War, Bunch found himself plunged into a double life, settling into an amiable routine with his slavery-loving neighbors on the one hand, while working furiously to thwart their plans to achieve a new Confederacy. As secession and war approached, the Southern states found themselves in an impossible position. They knew that recognition from Great Britain would be essential to the survival of the Confederacy, and also that such recognition was likely to be withheld if the South reopened the Atlantic slave trade. But as Bunch meticulously noted from his perch in Charleston, secessions red-hot epicenter, that trade was growing. And as Southern leaders continued to dissemble publicly about their intentions, Bunch sent dispatch after secret dispatch back to the Foreign Office warning of the truththat economic survival would force the South to import slaves from Africa in massive numbers. When the gears of war finally began to turn, and Bunch was pressed into service on an actual spy mission to make contact with the Confederate government, he found himself in the middle of a fight between the Union and Britain that threatened, in the boast of Secretary of State William Seward, to wrap the world in flames. In this masterfully told story, Christopher Dickey introduces Consul Bunch as a key figure in the pitched battle between those who wished to reopen the floodgates of bondage and misery, and those who wished to dam the tide forever. Featuring a remarkable cast of diplomats, journalists, senators, and spies, Our Man in Charleston captures the intricate, intense relationship between great powers on the brink of war. Originally published: New York: Crown, 2015. Shipping may be from multiple locations in the US or from the UK, depending on stock availability. Seller Inventory # 9780307887283

Our Man in Charleston: Britains Secret Agent in the Civil War South

Book Description Condition: New. . Seller Inventory # 52GZZZ00KBL8_ns

Our Man in Charleston: Britain's Secret Agent in the Civil War South

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 0307887286-2-1

Our Man in Charleston: Britain's Secret Agent in the Civil War South

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-0307887286-new