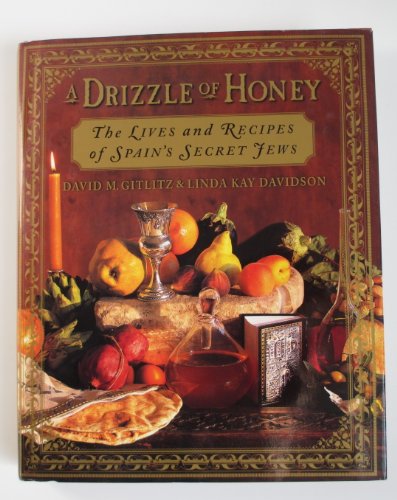

Items related to A Drizzle of Honey : The Lives and Recipes of Spain's...

When tens of thousands of Iberian Jews were converted to Catholicism under duress during the Inquisition, many rapidly assimilated to their new religious culture. Others, the crypto-Jews, struggled to retain their Jewish identity in private while projecting Christian conformity in the public sphere. In order to root out these "heretics," the courts of the Inquisition published checklists of Jewish household habits and koshering practices and grilled the servants, neighbors, and even the children of those suspected of practicing their religion at home.

From these testimonies and other primary sources, Gitlitz and Davidson have drawn a fascinating picture of the secret culinary life of the crypto-Jews and the customs and foods that threatened their existence while securing their precarious sense of identity. From nearly a hundred specific references to Sephardic cuisine, the authors have recreated these recipes. They combine Christian and Islamic traditions in cooking lamb, beef, fish, eggplants, chickpeas, and greens and use seasonings such as saffron, mace, ginger, and cinnamon. These recipes, with accompanying text that tells the stories of their creators, promise to delight the adventurous palate and give insights into the foundations of modern Sephardic cuisine.

From these testimonies and other primary sources, Gitlitz and Davidson have drawn a fascinating picture of the secret culinary life of the crypto-Jews and the customs and foods that threatened their existence while securing their precarious sense of identity. From nearly a hundred specific references to Sephardic cuisine, the authors have recreated these recipes. They combine Christian and Islamic traditions in cooking lamb, beef, fish, eggplants, chickpeas, and greens and use seasonings such as saffron, mace, ginger, and cinnamon. These recipes, with accompanying text that tells the stories of their creators, promise to delight the adventurous palate and give insights into the foundations of modern Sephardic cuisine.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

David and Linda Kay Davidson are professors at the University of Rhode Island. They are married and each has written several books on Spanish culture, including Gitlitz's Secrecy and Deceit, an alternate selection of the History Book Club and winner of the 1996 National Jewish Book Award for Sephardic Studies and the 1997 Lucy B. Dawidowicz Prize for History.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

A Drizzle of Honey

Recipes, Stories & CommentarySalads and VegetablesSalads tend to be eaten raw, while vegetables are usually cooked, but the line of demarcation between the two has always been a thin one. Beets, peas, and spinach, for example, are served both cold and hot; they can stand alone as a main dish or be mixed with other ingredients. Lettuce can be eaten cold in a salad or fried in oil, and its stalks can be boiled with lots of sugar to make a conserve.1Spanish culinary traditions and terminology complicate matters further. Spanish categories overlap: an hierba is a grass or an herb; a legumbre is a vegetable, but especially a legume; verdura gives the sense of something green; while an hortaliza is almost anything that grows in the huerta, or garden. All of these terms were used in the Middle Ages, sometimes interchangeably. Enrique de Villena's Arte cisoria (The Art of Carving) lists twenty "yerbas," including thistle, carrots, lettuce, turnips, onions, garlic, borage, purslane, fennel, caraway, and mustard.2 The seventeenth-century dictionary writer Covarrubiaseven uses the same two examples--lettuce and radishes--to illustrate two different categories, verduras and hortalizas. For Covarrubias, the legumbre has fruit that develops in a pod, while hierba denotes produce without stalks that can be either cooked in stews or served raw in salads.3In the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, salads must have been ubiquitous. The occasional references suggest that they included a wider variety of ingredients than are common today. Covarrubias defines "salad" (ensalada) as "different herbs, meats, salted [ingredients], fish, olives, conserves, condiments [,] egg yolks, borage, sugared almonds, and a great diversity of things ... ."4 He also tells us that its name derives from the custom of sprinkling the miscellany with salt (sal).5 The single salad recipe in the late fourteenth-century cookbook from the kitchens of English King Richard II lists more than a dozen different ingredients, including some still-common greens and herbs such as parsley, garlic, onions, and watercress, and others not quite so common: fennel, leeks, borage, mint, rue, and purslane.6 Renaissance literary references tell us about "sliced lettuces and carrots with oregano"7 and "onion ... artichoke ... and chopped cucumber."8 Sources such as these suggest that anything green and edible raw could be thrown into a salad, but that a salad was not limited to greens. Other ingredients depended only on what was seasonably available. In the temperate regions of the Iberian Peninsula, including the humid north where varieties of chard are common, people could count on salad greens during much of the year. Though rarely cited, seasonal varieties of lettuce were undoubtedly common in salads. People then believed that lettuce contained properties that calmed lust and thus it was the symbol for continence.9No matter what went into the salad, salt, vinegar, and oil were its constant dressing, and this is still the norm on the Spanish table. The account ledger of a sixty-eight-day journey in 1352 from Estella to Seville lists the purchase of vinegar on forty-three occasions generally accompanying some reference to salad makings, such as lettuce, radishes, and rocket. According to a Spanish proverb, "To make a good salad, four men are needed: for the salt, a wise man; for the oil, a prodigal man; for the vinegar, a stingy man; and to mix it, a crazy man ... ."10 Granado's recipe for cooked white beans insists that if they are to be served as a salad one must add vinegar and oil.11Elsewhere during the rest of the year, people largely consumed cabbage and root vegetables such as carrots, parsnips, and turnips. One popular proverb states, "There's nothing better than turnips with cabbage."12 Radishes were so common that they gave their name to several Iberian towns, such as the Salamancan and Leonese Rabanal. Other proverbs substantiate the radish's popularity: "A tender radish, no matter the size, isgood" and "There is no good life without radishes and candles."13 Covarrubias adds that radishes help people suffering from jaundice.14The list of vegetables common in Roman Iberia was expanded when the Muslims introduced Eastern products, notably the chickpea and the eggplant.15 The Al-Andalus cookbook gives a good sense of the vegetables commonly consumed in Islamic Spain. Its "garden recipe" is for a green dish to be made from whatever happened to be in the garden. The author lists for summer: chard, squash, eggplant, fennel, and melon; for spring he suggests lettuce, fennel, fresh beans, spinach, chard, and cilantro. The directions make clear that any combination of these also could be used to make a vegetable broth which was thickened with eggs.16 The vegetables mentioned in the rest of his book, such as cauliflower, turnips, artichokes, squash, and spinach, are generally a part of a stew or a seasoning for meat. One notable departure is an emphasis on the eggplant, for which the Al-Andalus cookbook offers more than a dozen recipes.A common characteristic of medieval cookbooks has been thought to be the scant attention they give to vegetables as stand-alone foods.17 However, two Christian Iberian cookbooks, Sent soví and Granado's, devote space to Lenten dishes featuring vegetables, usually prepared as thick stews. In fact, Granado devotes an entire section to vegetable stews (escudillas de yeruas), with individual recipes for borage, chard, spinach, lettuce, chicory, malva, asparagus, squash, and chickpeas, some of which are made with meat broth and others with almond milk.18 We also find recipes for artichokes, asparagus, leeks, squash, cabbage, and mushrooms.The medieval table included whatever was edible in its season. In addition, some vegetables were stored, or preserved, for later consumption when it was too cold for the greens to grow. We may infer that greens and legumes growing around the house were not highly prized, but they were eaten and probably eaten in great quantities, especially on non-meat days in the Christian calendar.19Jews and crypto-Jews shared the taste for salads and vegetables. There is no reason to believe that the salads eaten by the crypto-Jews differed in any way from those eaten by their old-Christian neighbors. On the other hand, based on the frequency of references specifically associating them with Iberian Jews, eggplant, greens like chard, and chickpeas, combining equally well with meat, fish, and fowl, seem to have been defining characteristics of medieval Sephardic vegetable cuisine.Juana Núñez's Lechugas Y RábanosLucia Fernández alleged that for lunch Juana Núñez used to give them "lettuce and radishes and cheese and cress and other things she does not remember."20Juana Nunez and her husband, Juan de Teva, a clothing merchant, practiced crypto-Judaism in Ciudad Real in the early sixteenth century. When the Inquisition's curiosity focused on the couple, Juan fled to Portugal. The Spanish Inquisition tried him in absentia and burned his effigy on September 7, 1513.21 Juana was arrested on March 3, 1512, and her trial dragged on for two and a half years. Juana got along poorly with her neighbors, and the pettiness of their squabbles is evident in the malice with which they shared gossip about her with the Inquisition.Malice aside, their testimony is rich in details about Juana's crypto-Jewish customs. For example, Juana and her closest women friends used to fast during daylight hours on Mondays and Thursdays. According to one neighbor, in the afternoons when Juana's sons Hernandico (twelve years old) and Antonito (thirteen years old) came home from school, to show their respect they would kiss their mother's hand in the Jewish fashion, and she would put her hand on their heads and draw it down across their faces, but without making the sign of the cross.Above all, Juana tended to keep the Sabbath fully, on Friday sweeping and scrubbing her house, preparing food to be kept warm until Saturday, and taking a bath with her crypto-Jewish friends Maria Gonzalez and Luisa Fernández and their daughters. She heated water in a large tub, into which she sprinkled rosemary and orange peels. After the bath, according to her servant Lucia Fernández, wife of the shepherd Francisco de Lillo, she used to hop straight into bed with her husband without quarreling the way they did on other weeknights. She had several strategies to abstain from working during the Sabbath. Again according to Lucia, her favorite was to pretend she had a headache and to throw herself down on some pillows until Saturday afternoon, when she routinely recovered and invited her women friends to her house for a social late afternoon to talk and snack and make jokes about the Catholic mass. It was at these Sabbath gatherings that Juana used to serve this salad.The Inquisition found Juana guilty of Judaizing, but because so many of the prosecution witnesses were shown to be biased against her, Juana's sentence was relatively light: to remain under house arrest, to wear the penitential San Benito robe, to abstain from wearing jewelry or any adornment, and to make confession a minimum of three times annually. Ten months later, at Juana's petition, even these minor sentences were commuted.Juana Núñez's Lettuce and Radish SaladServes 4-6Salad1--2 ounces watercress 1/2 head green lettuce 2 cups torn-up other greens, such as a combination of radicchio, red lettuce, romaine, endive, or fennel 1 tablespoon chopped fresh mint 3--4 radishes, sliced 1--2 ounces grated hard cheese, such as Romano or Manchego 1--2 teaspoons coarsely ground sea saltDressing1--2 teaspoons balsamic, cider, or red wine vinegar3 tablespoons olive oil1. Remove the stems from the watercress. Chop the leaves into bite-size pieces.2. Tear the lettuce into bite-size pieces. Toss all the greens together in a large bowl.3. Top with the radishes and cheese.4. Sprinkle with the salt.5. Make the dressing: Pour the vinegar into a jar; add the olive oil. Cover and shake vigorously.6. Pour the dressing over the salad and toss well before serving, or pass a cruet at the table.María Sánchez's VerdurasMaria Sánchez testified that on Saturday in Guadalupe she had seen "lots of conversa women sitting by the doors of their houses eating greens with vinegar."22María Sanchez, the widow of the butcher Diego Ximenez of Guadalupe, was herself tried in 1485--86. The most damaging testimony came from her daughter Ines, who was also a prisoner. She told inquisitors that her mother had most likely confessed to all their Judaizing customs except three: that after the baptism of her son Diego she had scrubbed off the chrism; that she frequently donated oil for the lamps in the synagogue in Trujillo; and that she had taken the crucifix that her now-deceased husband had hung at the foot of their bed and had thrown it in the privy. Ines reported that when she went into her mother's cell she found her despondent, moaning that she would be killed for what she had confessed. Ines said that she had asked her mother if she had mentioned the crucifix to the inquisitors, to which Maria replied, "Daughter, nobody knows it but you; so tell me if you talked about it, for if you didn't I won't say anything."23 The fact that we have this datum proves that this attempt at collusion failed.A principal witness against Maria was a serving girl who had become a confidante of one of Maria's daughters. The daughter explained to her in great detail how in the time before the founding of the Inquisition the local crypto-Jewish community was accustomed to observing the Sabbath, and how in the afternoons they used to gather in the doorway of someone's house to talk and munch on greens with vinegar.María went to the stake on November 20, 1486.24

We have seen that the Spanish term verdura encompasses any edible green grown in the garden. The greens could have been eaten raw or cooked, sprinkled with vinegar or, perhaps, vinegar and oil. It is common in modern-day Spain to sprinkle vinegar over cooked green vegetables such as chard. Because we already have a number of clear references to salads that were eaten with vinegar, we have opted to interpret this reference to greens as a vegetable dish. Since we cannot be sure if the greens were cooked or not, we offer two recipes for this dish.María Sánchez's GreensAs a cold DishServes 41 large bunch of greens (see Variations) 2 tablespoons other finely chopped fresh green herbs (see Variations) 1--2 tablespoons balsamic or red vinegar 1/2 teaspoon coarsely ground sea salt1. Wash the greens and pat them dry. Cut them into bite-size pieces and place them and the herbs in a large bowl. You should have about 8 cups.2. Sprinkle with the vinegar and sea salt.3. Mix well and serve.As a Hot DishServes 41 large bunch of greens (see Variations) 1--3 tablespoons olive oil 2 tablespoons other finely chopped fresh green herbs (see Variations) 1--2 tablespoons balsamic or red vinegar 1/2 teaspoon coarsely ground sea salt1. Wash the greens and pat them dry. Chop them into medium-size pieces.2. In a medium skillet, heat the olive oil over medium heat. Toss in the greens and herbs and stir-fry briefly Sprinkle the vinegar over the greens and stir it in. Continue to fry just until the vinegar has been absorbed, about 2 or 3 minutes.3. Sprinkle with the salt and serve immediately.VARIATIONSAny green or combination of flavorful greens is possible. It is best to balance peppery or spicy flavors, like turnip, lovage, or mustard greens, with more bland ones, such as lettuces, radicchio, or spinach.The herbs add diversity to the greens. Here are some possibilities:2 tablespoons chopped chives or onions 1 teaspoon chopped fresh marjoram 1/2 teaspoon chopped fresh oregano 1/2 teaspoon chopped fresh dill or fennel 1 tablespoon chopped nasturtium leaves 2 teaspoons chopped fresh basilMaría Alvarez's Acelgas Ahogadas en AceiteIn the Sorian city of Almazán in 1505, María Alvarez allegedly prepared "Swiss chard, parboiling it in water and then frying it with onions in oil, and then boiling it again in the oil. And then she threw in water and grated bread crumbs and spices and egg yolks; and she cooked it until it got very thick."25Medieval recipes generally distinguished between spices, herbs, and greens. Greens grew locally and were eaten as what we today term "vegetables," generally in meat stews. The leaves of other pla...

Recipes, Stories & CommentarySalads and VegetablesSalads tend to be eaten raw, while vegetables are usually cooked, but the line of demarcation between the two has always been a thin one. Beets, peas, and spinach, for example, are served both cold and hot; they can stand alone as a main dish or be mixed with other ingredients. Lettuce can be eaten cold in a salad or fried in oil, and its stalks can be boiled with lots of sugar to make a conserve.1Spanish culinary traditions and terminology complicate matters further. Spanish categories overlap: an hierba is a grass or an herb; a legumbre is a vegetable, but especially a legume; verdura gives the sense of something green; while an hortaliza is almost anything that grows in the huerta, or garden. All of these terms were used in the Middle Ages, sometimes interchangeably. Enrique de Villena's Arte cisoria (The Art of Carving) lists twenty "yerbas," including thistle, carrots, lettuce, turnips, onions, garlic, borage, purslane, fennel, caraway, and mustard.2 The seventeenth-century dictionary writer Covarrubiaseven uses the same two examples--lettuce and radishes--to illustrate two different categories, verduras and hortalizas. For Covarrubias, the legumbre has fruit that develops in a pod, while hierba denotes produce without stalks that can be either cooked in stews or served raw in salads.3In the late Middle Ages and Renaissance, salads must have been ubiquitous. The occasional references suggest that they included a wider variety of ingredients than are common today. Covarrubias defines "salad" (ensalada) as "different herbs, meats, salted [ingredients], fish, olives, conserves, condiments [,] egg yolks, borage, sugared almonds, and a great diversity of things ... ."4 He also tells us that its name derives from the custom of sprinkling the miscellany with salt (sal).5 The single salad recipe in the late fourteenth-century cookbook from the kitchens of English King Richard II lists more than a dozen different ingredients, including some still-common greens and herbs such as parsley, garlic, onions, and watercress, and others not quite so common: fennel, leeks, borage, mint, rue, and purslane.6 Renaissance literary references tell us about "sliced lettuces and carrots with oregano"7 and "onion ... artichoke ... and chopped cucumber."8 Sources such as these suggest that anything green and edible raw could be thrown into a salad, but that a salad was not limited to greens. Other ingredients depended only on what was seasonably available. In the temperate regions of the Iberian Peninsula, including the humid north where varieties of chard are common, people could count on salad greens during much of the year. Though rarely cited, seasonal varieties of lettuce were undoubtedly common in salads. People then believed that lettuce contained properties that calmed lust and thus it was the symbol for continence.9No matter what went into the salad, salt, vinegar, and oil were its constant dressing, and this is still the norm on the Spanish table. The account ledger of a sixty-eight-day journey in 1352 from Estella to Seville lists the purchase of vinegar on forty-three occasions generally accompanying some reference to salad makings, such as lettuce, radishes, and rocket. According to a Spanish proverb, "To make a good salad, four men are needed: for the salt, a wise man; for the oil, a prodigal man; for the vinegar, a stingy man; and to mix it, a crazy man ... ."10 Granado's recipe for cooked white beans insists that if they are to be served as a salad one must add vinegar and oil.11Elsewhere during the rest of the year, people largely consumed cabbage and root vegetables such as carrots, parsnips, and turnips. One popular proverb states, "There's nothing better than turnips with cabbage."12 Radishes were so common that they gave their name to several Iberian towns, such as the Salamancan and Leonese Rabanal. Other proverbs substantiate the radish's popularity: "A tender radish, no matter the size, isgood" and "There is no good life without radishes and candles."13 Covarrubias adds that radishes help people suffering from jaundice.14The list of vegetables common in Roman Iberia was expanded when the Muslims introduced Eastern products, notably the chickpea and the eggplant.15 The Al-Andalus cookbook gives a good sense of the vegetables commonly consumed in Islamic Spain. Its "garden recipe" is for a green dish to be made from whatever happened to be in the garden. The author lists for summer: chard, squash, eggplant, fennel, and melon; for spring he suggests lettuce, fennel, fresh beans, spinach, chard, and cilantro. The directions make clear that any combination of these also could be used to make a vegetable broth which was thickened with eggs.16 The vegetables mentioned in the rest of his book, such as cauliflower, turnips, artichokes, squash, and spinach, are generally a part of a stew or a seasoning for meat. One notable departure is an emphasis on the eggplant, for which the Al-Andalus cookbook offers more than a dozen recipes.A common characteristic of medieval cookbooks has been thought to be the scant attention they give to vegetables as stand-alone foods.17 However, two Christian Iberian cookbooks, Sent soví and Granado's, devote space to Lenten dishes featuring vegetables, usually prepared as thick stews. In fact, Granado devotes an entire section to vegetable stews (escudillas de yeruas), with individual recipes for borage, chard, spinach, lettuce, chicory, malva, asparagus, squash, and chickpeas, some of which are made with meat broth and others with almond milk.18 We also find recipes for artichokes, asparagus, leeks, squash, cabbage, and mushrooms.The medieval table included whatever was edible in its season. In addition, some vegetables were stored, or preserved, for later consumption when it was too cold for the greens to grow. We may infer that greens and legumes growing around the house were not highly prized, but they were eaten and probably eaten in great quantities, especially on non-meat days in the Christian calendar.19Jews and crypto-Jews shared the taste for salads and vegetables. There is no reason to believe that the salads eaten by the crypto-Jews differed in any way from those eaten by their old-Christian neighbors. On the other hand, based on the frequency of references specifically associating them with Iberian Jews, eggplant, greens like chard, and chickpeas, combining equally well with meat, fish, and fowl, seem to have been defining characteristics of medieval Sephardic vegetable cuisine.Juana Núñez's Lechugas Y RábanosLucia Fernández alleged that for lunch Juana Núñez used to give them "lettuce and radishes and cheese and cress and other things she does not remember."20Juana Nunez and her husband, Juan de Teva, a clothing merchant, practiced crypto-Judaism in Ciudad Real in the early sixteenth century. When the Inquisition's curiosity focused on the couple, Juan fled to Portugal. The Spanish Inquisition tried him in absentia and burned his effigy on September 7, 1513.21 Juana was arrested on March 3, 1512, and her trial dragged on for two and a half years. Juana got along poorly with her neighbors, and the pettiness of their squabbles is evident in the malice with which they shared gossip about her with the Inquisition.Malice aside, their testimony is rich in details about Juana's crypto-Jewish customs. For example, Juana and her closest women friends used to fast during daylight hours on Mondays and Thursdays. According to one neighbor, in the afternoons when Juana's sons Hernandico (twelve years old) and Antonito (thirteen years old) came home from school, to show their respect they would kiss their mother's hand in the Jewish fashion, and she would put her hand on their heads and draw it down across their faces, but without making the sign of the cross.Above all, Juana tended to keep the Sabbath fully, on Friday sweeping and scrubbing her house, preparing food to be kept warm until Saturday, and taking a bath with her crypto-Jewish friends Maria Gonzalez and Luisa Fernández and their daughters. She heated water in a large tub, into which she sprinkled rosemary and orange peels. After the bath, according to her servant Lucia Fernández, wife of the shepherd Francisco de Lillo, she used to hop straight into bed with her husband without quarreling the way they did on other weeknights. She had several strategies to abstain from working during the Sabbath. Again according to Lucia, her favorite was to pretend she had a headache and to throw herself down on some pillows until Saturday afternoon, when she routinely recovered and invited her women friends to her house for a social late afternoon to talk and snack and make jokes about the Catholic mass. It was at these Sabbath gatherings that Juana used to serve this salad.The Inquisition found Juana guilty of Judaizing, but because so many of the prosecution witnesses were shown to be biased against her, Juana's sentence was relatively light: to remain under house arrest, to wear the penitential San Benito robe, to abstain from wearing jewelry or any adornment, and to make confession a minimum of three times annually. Ten months later, at Juana's petition, even these minor sentences were commuted.Juana Núñez's Lettuce and Radish SaladServes 4-6Salad1--2 ounces watercress 1/2 head green lettuce 2 cups torn-up other greens, such as a combination of radicchio, red lettuce, romaine, endive, or fennel 1 tablespoon chopped fresh mint 3--4 radishes, sliced 1--2 ounces grated hard cheese, such as Romano or Manchego 1--2 teaspoons coarsely ground sea saltDressing1--2 teaspoons balsamic, cider, or red wine vinegar3 tablespoons olive oil1. Remove the stems from the watercress. Chop the leaves into bite-size pieces.2. Tear the lettuce into bite-size pieces. Toss all the greens together in a large bowl.3. Top with the radishes and cheese.4. Sprinkle with the salt.5. Make the dressing: Pour the vinegar into a jar; add the olive oil. Cover and shake vigorously.6. Pour the dressing over the salad and toss well before serving, or pass a cruet at the table.María Sánchez's VerdurasMaria Sánchez testified that on Saturday in Guadalupe she had seen "lots of conversa women sitting by the doors of their houses eating greens with vinegar."22María Sanchez, the widow of the butcher Diego Ximenez of Guadalupe, was herself tried in 1485--86. The most damaging testimony came from her daughter Ines, who was also a prisoner. She told inquisitors that her mother had most likely confessed to all their Judaizing customs except three: that after the baptism of her son Diego she had scrubbed off the chrism; that she frequently donated oil for the lamps in the synagogue in Trujillo; and that she had taken the crucifix that her now-deceased husband had hung at the foot of their bed and had thrown it in the privy. Ines reported that when she went into her mother's cell she found her despondent, moaning that she would be killed for what she had confessed. Ines said that she had asked her mother if she had mentioned the crucifix to the inquisitors, to which Maria replied, "Daughter, nobody knows it but you; so tell me if you talked about it, for if you didn't I won't say anything."23 The fact that we have this datum proves that this attempt at collusion failed.A principal witness against Maria was a serving girl who had become a confidante of one of Maria's daughters. The daughter explained to her in great detail how in the time before the founding of the Inquisition the local crypto-Jewish community was accustomed to observing the Sabbath, and how in the afternoons they used to gather in the doorway of someone's house to talk and munch on greens with vinegar.María went to the stake on November 20, 1486.24

We have seen that the Spanish term verdura encompasses any edible green grown in the garden. The greens could have been eaten raw or cooked, sprinkled with vinegar or, perhaps, vinegar and oil. It is common in modern-day Spain to sprinkle vinegar over cooked green vegetables such as chard. Because we already have a number of clear references to salads that were eaten with vinegar, we have opted to interpret this reference to greens as a vegetable dish. Since we cannot be sure if the greens were cooked or not, we offer two recipes for this dish.María Sánchez's GreensAs a cold DishServes 41 large bunch of greens (see Variations) 2 tablespoons other finely chopped fresh green herbs (see Variations) 1--2 tablespoons balsamic or red vinegar 1/2 teaspoon coarsely ground sea salt1. Wash the greens and pat them dry. Cut them into bite-size pieces and place them and the herbs in a large bowl. You should have about 8 cups.2. Sprinkle with the vinegar and sea salt.3. Mix well and serve.As a Hot DishServes 41 large bunch of greens (see Variations) 1--3 tablespoons olive oil 2 tablespoons other finely chopped fresh green herbs (see Variations) 1--2 tablespoons balsamic or red vinegar 1/2 teaspoon coarsely ground sea salt1. Wash the greens and pat them dry. Chop them into medium-size pieces.2. In a medium skillet, heat the olive oil over medium heat. Toss in the greens and herbs and stir-fry briefly Sprinkle the vinegar over the greens and stir it in. Continue to fry just until the vinegar has been absorbed, about 2 or 3 minutes.3. Sprinkle with the salt and serve immediately.VARIATIONSAny green or combination of flavorful greens is possible. It is best to balance peppery or spicy flavors, like turnip, lovage, or mustard greens, with more bland ones, such as lettuces, radicchio, or spinach.The herbs add diversity to the greens. Here are some possibilities:2 tablespoons chopped chives or onions 1 teaspoon chopped fresh marjoram 1/2 teaspoon chopped fresh oregano 1/2 teaspoon chopped fresh dill or fennel 1 tablespoon chopped nasturtium leaves 2 teaspoons chopped fresh basilMaría Alvarez's Acelgas Ahogadas en AceiteIn the Sorian city of Almazán in 1505, María Alvarez allegedly prepared "Swiss chard, parboiling it in water and then frying it with onions in oil, and then boiling it again in the oil. And then she threw in water and grated bread crumbs and spices and egg yolks; and she cooked it until it got very thick."25Medieval recipes generally distinguished between spices, herbs, and greens. Greens grew locally and were eaten as what we today term "vegetables," generally in meat stews. The leaves of other pla...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSt. Martin's Press

- Publication date1999

- ISBN 10 0312198604

- ISBN 13 9780312198602

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages332

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 350.00

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

A Drizzle of Honey : The Lives and Recipes of Spain's Secret Jews

Published by

St. Martin's Press

(1999)

ISBN 10: 0312198604

ISBN 13: 9780312198602

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # VIB0312198604

Buy New

US$ 350.00

Convert currency