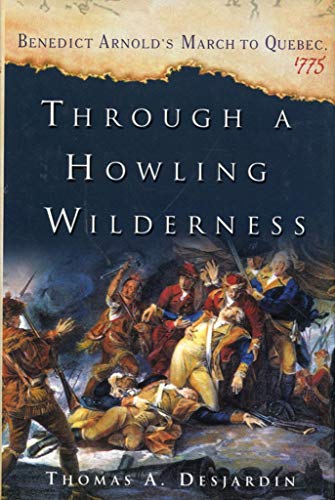

Items related to Through a Howling Wilderness: Benedict Arnold's...

The march, under the command of Colonel Benedict Arnold, proved to be a tragic journey. Before they reached the outskirts of Quebec, hundreds died from hypothermia, drowning, small pox, lightning strikes, exposure, and starvation. The survivors ate dogs, shoes, clothing, leather, cartridge boxes, shaving soap, and lip salve. Their trek toward Quebec was nearly twice the length shown on their maps. In the midst of the journey, the most unlikely of events befell them: a hurricane. The rains fell in such torrents that their boats floated off or sunk, taking their meager provisions along, and then it began to snow. The men woke up frozen in their tattered clothing. One third of the force deserted, returning to Massachusetts. Of those remaining, more than four hundred were killed, wounded, or taken prisoner.

Finally, in the midst of a raging blizzard, those remaining attacked Quebec. In the assault, their wet muskets failed to fire. Undaunted, they overtook the first of two barricades and pressed on toward the other, nearly taking Canada from the British. Demonstrating Benedict Arnold's prowess as a military strategist, the attack on Quebec accomplished another goal for the colonial army: It forced the British to commit thousands of troops to Canada, subsequently weakening the British hand against George Washington.

A great military history about the early days of the American Revolution, Through a Howling Wilderness is also a timeless adventure narrative that tells of heroic acts, men pitted against nature's fury, and a fledgling nation's fight against a tyrannical oppressor.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

The Fourteenth Colony

He came within view of his father's house a little past noon on a pleasant late-September day. Eighteen months had passed since he had left this home in Bridgewater of the Colony of Massachusetts to join the army of George Washington, and in that time he had taken part in adventures and hardships that people in his hometown only read about in novels---those that could read and had time for novels. During his service he had fought at Bunker Hill, then sailed to the Province of Maine with an army under Colonel Benedict Arnold, walked, waded, and swam hundreds of miles through the Maine wilderness to the city of Quebec.

Along the way this simple farmer watched men around him die of hypothermia, drowning, and drunken violence. Smallpox, and falling trees killed his fellow soldiers. He saw friends die from exposure and exhaustion, from starvation and from eating too quickly after starvation. To survive, men ate dogs, shoes, clothing, leather, cartridge boxes, shaving soap, tree sap, and lip salve. If they survived, they suffered from gout, rheumatism, dysentery, angina, distemper, diarrhea, constipation, pneumonia, swollen limbs, and infestation.

With the comrades who survived, he attacked a naturally fortified city that contained a military force larger than their own, made up of soldiers from the most powerful empire the world had ever known. When the attack failed, he was captured and thrown into a dungeonlike British prison where he nearly perished from smallpox. He was then pressed into service on a British ship for months, until he, along with two other comrades, escaped and walked back through the Maine wilderness, hundreds of miles, to civilization. On the return trip, they encountered the bones of the men who had died on the way to Quebec the year before. Back among colonial villages, they sailed as laborers on a vessel bound for Boston, a few days walk from Bridgewater.

Now, as he approached the comforts and safety of home, he little resembled the fresh-faced teenager who had left to fight for the Rebel cause just after Lexington-Concord. His trials had left him haggard, his skin pitted by smallpox, and his appearance greatly altered. Unconscious of the effect his sudden and gaunt appearance might have on his loved ones, he simply entered through the open door, nodded his head, and sat down in a chair just inside without uttering a word. His mother was across the room sewing and looked up when he entered, but, thinking he was a passing stranger stopping for rest or refreshment, she went back to her needlework without even a greeting.

His young sister, not yet a teenager, took note of him next and, with the curiosity of a youngster, eyed him closely for a time. Suddenly she exclaimed "La, if there ain't Simon!"

At this his mother, who had given him up for dead months earlier, nearly fainted, and as the news of his return spread through the countryside, his father and brother came to confirm the rumor. That evening, friends from miles around came to the modest home to hear his stories of great adventure and suffering. Simon Fobes was home from the war and had a tale to tell of one of the greatest military expeditions in American history.

Quebec City had been the hub of civilization in its region since Samuel de Champlain first sailed up the St. Lawrence River in 1603. Here he encountered a native settlement on a prominent hill of solid rock that lay between the fork made by the St. Lawrence and one of its major tributaries. The Algonquins who used the site called it "Kebec," meaning "where the river narrows," and it must have struck Champlain as a natural and ideal base of operation for future exploration and colonization. The high rock slope rising from the rivers made it a site one could easily defend against attack, while the half-dozen rivers that converged into the St. Lawrence within ten miles made it ideal for transportation of trade goods and supplies to and from the surrounding wilderness. Even this far inland, the deep waters of the St. Lawrence provided easy access to the sea and Europe. In subsequent voyages, Champlain inquired about Quebec of the natives he encountered elsewhere, and he learned that its trading potential stretched nearly as far as he explored, all the way to the southern coast of Maine.

Two years later, he sailed to Maine's Penobscot Bay and up the navigable length of its river to what is now Bangor. There he learned from the natives that one could reach Quebec by way of a series of lakes, "and, when they reach the end, they go some distance by land, and afterward enter a little river which flows into the St. Lawrence."

The following year he learned of yet another route, farther west, by way of the Kennebec River. "One can go from this river across the land so far as Quebec," he recalled, "some 50 leagues, without passing more than one portage of two leagues. Then one enters another little river which empties into the great River St. Lawrence."

This was the first time any white man ever heard of what would later be known as the Kennebec-Chaudière trail, though the natives apparently failed to mention the difficulties that lay along this path.

Convinced of the potential of the Quebec site, in 1608 Champlain led a group of thirty-two colonists to settle there and establish it as a trading center, primarily for furs. Only nine colonists survived their first Canadian winter, but the colony endured, and more settlers arrived the following summer. For the next century and a half, the citadel at Quebec was a focal point of fighting between the British and French empires until 1759, when the city fell into English hands after the pivotal Battle of the Plains of Abraham.

The generals commanding each side in this fight, Montcalm for the French and Wolfe for the British, died in the fighting, and the British seized the city. By 1761, fighting in the so-called French and Indian Wars had dwindled to a close, and the two European powers signed a formal peace treaty in Paris on February 10, 1763. By this agreement, France relinquished all of its claims to North America, leaving tens of thousands of French settlers in Quebec Province subject to British rule.

Eleven years after the Treaty of Paris solidified England's authority over the province, the British Parliament passed what became known as the Quebec Act of 1774, instituting a permanent administration in Canada by replacing the temporary English-style government created in 1763 with a French form of civil law, while maintaining the British system of criminal law. In addition, it gave French Canadians complete religious freedom---a direct threat, as the other colonies saw it, "to dispose the inhabitants to act with hostility against the free Protestant Colonies, whenever a wicked Ministry shall chuse so to direct them."

Representatives of the lower thirteen colonies soon listed it among the so-called Intolerable Acts, about which they pled with King George for relief. When he ignored their plea, they turned to open rebellion.

By the mid-1770s, Champlain's Quebec had grown into a huge province stretching to the Mississippi River and including modern-day Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. It was home to eighty thousand inhabitants, though only 2 percent of them spoke English. Despite its official status as a North American colony under British rule, Quebec never became a part of the coalition of colonies that eventually declared their independence in 1776. Language and religious differences set the Québecois well apart from their neighbors to the south, and when representatives of the lower thirteen colonies met at the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia in 1774, no delegate from Quebec answered the roll. As the Protestant colonies then saw it, Catholic Quebec existed "to the great danger, from so great a dissimilarity of Religion, law, and government, of the neighboring British colonies by the assistance of whose blood and treasure the said country was conquered from France."

Once fighting had broken out between colonists and soldiers of the Crown, however, some in the lower thirteen began to see the advantages of enlisting the fourteenth colony to the north. Aside from alleviating the danger they felt from their northern neighbors, gaining the support of eighty thousand French, who were predisposed to British-hating anyway, could create a decided advantage in their designs against the mother country. At the very least, removing the British strongholds at Quebec and Montreal would eliminate any threat against the colonies from that region, effectively quashing British attempts to open a northern front in the newly begun conflict from which it could march an army south and cut the colonies in half.

If there was to be a fourteenth colony in the struggle against England, those in favor of it would find an obstacle in their way that would prove to be even more formidable than the high stone walls of Quebec. Governor Guy Carleton had returned to Quebec City from London in 1774 having married, become a father twice over, and seen to the passage of the act the colonists were then listing among the intolerable. Carleton's Quebec Act allowed the Québecois to worship as Catholics even though this was illegal in England itself. It also retained the French system of land tenure, and even let them speak French while serving in public offices. This was a remarkable feat for the governor, since it showed not only his understanding of his subjects and how best to placate them, but also his ability to persuade the British Parliament to go to such unusual lengths to do so. With the same stroke, Carleton had also seen his dominion of Quebec expand westward all the way to the Mississippi River.

However it was that Carleton swayed Parliament to grant him such requests, it certainly had nothing to do with his personal charm, which he seemed to lack altogether. Cold and aloof, he was, as an officer who served under him once wrote, "one of the most distant, reserved men in the world; he has a rigid strictness in his manner very unpleasing and which he observes even to his most particular friends and acquantances [sic]." Even General James Wolfe, hardly a model of good humor himself but one of the governor's closest friends, described him as "grave Carleton."

Still, he was considered the very model of an eighteenth-century British officer. At fifty years of age, he was six feet tall, with a high forehead that his hairline seemed to have largely abandoned. Born in Ireland to English gentry, he joined the British Army as an ensign in 1742, during the War of Austrian Succession. He later served as Wolfe's quartermaster general and chief engineer during the campaign that ended, along with Wolfe's life, on the Plains of Abraham, when the British seized Quebec from the French in 1759. He was wounded two years afterward, leading an assault against the French island of Belle-ële off the Brittany coast, and again the following year, assaulting Morro Castle in Havana, Cuba.

Carleton was active and energetic in his work, and King George III once wrote that his "uncorruptness is universally acknowledged."

Years later, a soldier under his command at Quebec would say, "There is not perhaps in the world a more experienced or more determined officer than General Carleton."

In 1766, with the help of his benefactor the Duke of Richmond, Carleton gained the King's appointment as lieutenant governor of Quebec and brigadier general in America. Two years later, King George elevated him to governor.

Returning from London in 1774, Carleton was well aware of the rebellion brewing in the other American colonies, and he hoped that his work with Parliament back home would pay dividends in Quebec. As a rule, the French inhabitants warmly received the news of the Quebec Act and its concessions to their religion and law.

In September 1774, Carleton sent two regiments to Massachusetts to help with the unrest there. This severely depleted his defensive forces at Quebec, where he found the Québecois ambivalent about the city's defense, and the French idea of employing Native Americans out of the question. Carleton winced at the brutality shown by natives toward colonists, including innocent civilians, and he "would not even suffer a Savage to pass the Frontier [into the lower colonies], though often urged to let them loose on the Rebel Provinces, lest cruelties might have been committed, and for fear the innocent might have suffered with the Guilty."

In addition, the boiling cauldron of insurrection in the lower colonies meant that he would get no help from London. In the summer of 1775, he wrote to a friend, "The situation of the King's affairs in [Massachusetts] leaves no room in the present moment for any consideration [other] than that . . . of augmenting the army under general Gage [in Boston]."

On May 19, 1775, a month-old letter arrived from General Thomas Gage stating that hostilities had broken out in Massachusetts. The following day, a courier arrived with word "that one Benedict Arnold said to be a native of Connecticut and a Horse Jockey" had led five hundred colonists in taking British outposts at Ticonderoga and Crown Point and had even penetrated to Saint Jean, within the boundaries of Quebec Province. It was not the last Carleton would hear of this horse jockey.

Down in the troubled and troublesome Colony of Massachusetts, the shooting at Lexington and Concord had shifted the disagreements with the King from political to military in April. A growing colonial force had fought at Bunker Hill against the British in June, and though the King's soldiers could claim a narrow victory in the fight, the colonists had shown that they were something more effective than an organized mob. As a result, they held the British garrison in Boston under siege while volunteers and militia groups from as many as hundreds of miles away rushed to join the now swelling colonial ranks. Daniel Morgan marched his Virginia rifle company six hundred miles in twenty-one days, and Michael Cressap's Maryland company covered 550 miles in twenty-two days to join the rebellion. On July 3, General George Washington, carrying his appointment as commander-in-chief of the colonial forces from the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, arrived in Cambridge to take command.

Among those anxious to rally around the patriot cause was a prominent trader and merchant from New Haven, Connecticut, who had made his fortune sailing goods from the West Indies to ports such as New York, Boston, Montreal, and Quebec. Energetic to an extreme and often impetuous, he had graying hair by 1775, giving him an air of maturity, but at thirty-four he remained a man of unusual strength and agility. He was of average height for his time, but his steel eyes, prominent nose, and a tendency to speak in a crisp and succinct manner gave those who encountered him cause to grant an instant respect. Though he had made himself one of the wealthiest men in the Colony of Connecticut, he was not of like mind with many of the "old guard" patriarchs of New Haven, who resisted the growing disagreements with the mother country. Instead, he seemed anxious not only to witness the outbreak of military action between King and colonies, but to participate in them personally, even though it meant risking his fortune.

As political tensions grew, Arnold helped form, and was elected captain of, the Governor's Second Company of Guards. When he received news of the fighting at Lexington and Concord, he started for Cambridge to join the forces gathering there. Realizing that the colonials had little powder and almost no cannons, Arnold turned his attention to t...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSt. Martin's Press

- Publication date2006

- ISBN 10 0312339046

- ISBN 13 9780312339043

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages256

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Through a Howling Wilderness: Benedict Arnold's March to Quebec, 1775

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0312339046

Through a Howling Wilderness: Benedict Arnold's March to Quebec, 1775

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon0312339046

Through a Howling Wilderness: Benedict Arnold's March to Quebec, 1775

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0312339046

Through a Howling Wilderness: Benedict Arnold's March to Quebec, 1775

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0312339046

Through a Howling Wilderness: Benedict Arnold's March to Quebec, 1775

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0312339046

Through a Howling Wilderness: Benedict Arnold's March to Quebec, 1775

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0312339046

Through a Howling Wilderness: Benedict Arnold's March to Quebec, 1775

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: Brand New. 256 pages. 8.50x5.75x1.25 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # 0312339046

Through a Howling Wilderness: Benedict Arnold's March to Quebec, 1775

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks82698

Through a Howling Wilderness: Benedict Arnold's March to Quebec, 1775 Desjardin, Thomas A.

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # XF3--0057

THROUGH A HOWLING WILDERNESS: BE

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.8. Seller Inventory # Q-0312339046