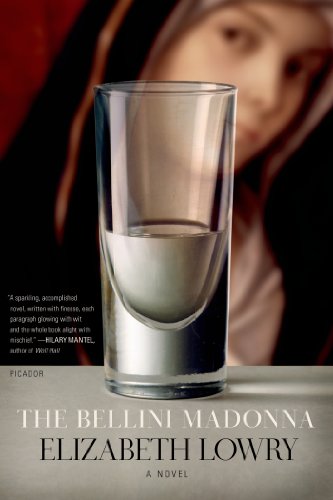

Items related to The Bellini Madonna

Thomas Lynch was once a brilliant young art historian. Now he is a disgraced, middle-aged art historian, overly fond of the bottle and of his fresh young students. But everything will change now that he's on the trail of a lost masterpiece, a legendary Madonna by the Italian master Giovanni Bellini.Insinuating himself into the crumbling English manor house where the painting could be concealed, Lynch discovers that his search had just begun and he himself may be the pawn in a more elaborate game. A Victorian diary that draws Robert Browning into the complicated provenance might provide the key€”if only Lynch can manage to beat his hosts in the search. Interlaced with complex clues and hidden jokes, "this sophisticated, parodic puzzle" (Booklist) reels from the lush English countryside to the sternly lovely hill towns of the Veneto, from the fifteenth century to the twenty-first.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Elizabeth Lowry has worked as an editor of the Oxford English Dictionary and as the deputy headmistress of a girls’ school. She contributes frequently to the London Review of Books and The Times Literary Supplement, and has also written for Harper’s Magazine and Granta. She lives in Oxfordshire. This is her first novel.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

Chapter One I met Anna Roper last month while I was trying to rob her at her home, in the village of Mawle in Berkshire. I write this. I write this to explain—no, that is not the beginning. Let me start again. I write this out of an overwhelming need to confess, to record, and, just possibly, to apologize. There. I have set down the first few strokes of the pattern. To apologize to whom? To Anna? To myself, for making such a hopeless hash of everything? Or to the universe? I feelthat it somehow deserves my most abject assurances of regret. I know that running away to Asolo now, at the end of this terrible summer, was a mistake. The stones of the buildings are still as ripe with sun as honeycombs, fat and warm with false promise. The Italian sun itself rises each day as though nothing has happened, awful in its innocence. Only the noonday shutters avert their faces, as if in sorrow or in shame. So this is what has become of my life’s ambition— There was a moment, on the flight over, when it all seemed insignificant. As the plane flopped down through the crevasse ofsummer sky that opened sheer above Treviso, the true proportions of things were suddenly revealed: a toy cow; a child’s blue hair ribbon, negligently draped in imitation of a stream; a putty church. The last three weeks were erased. They belongedelsewhere, to another time and place. Here everything was newly hatched, blameless. I took a fierce gulp of airplane gin and peered down through the dusty doubled glass of the window at a landscape that, miraculously, did not contain me. If I could have held things there forever, with my maudlin, drunken self permanently suspended above the unsuspecting life below, Iswear I would have. But then the craft dipped and we were plummeting down toward the black lip of a reservoir, a looming farm, the un-scrolling tarmac of a landing strip. I had arrived in Italy, and within a few minutes everything was life-sized again. My confession should begin here. My name is Thomas Joseph Lynch. I am fifty years old and until last year I was an art historian. In spite of everything, the term still suggests to me something harmlessly quixotic: a savant in a skullcap, a scholar in his robe; or at the very least a distinguished old fart with elbow patches, dedicated to the complex understanding ofsimple beauty. Simple beauty! As if the human eye is capable of perceiving any such thing! We cook up meanings, endless interpretations of what is. We smear and smudge everything with our quest for pattern, with our insane appetite for words— Let me introduce a lapidary pause while the camera lenses sparkle and flash in the chilly shadows of the temple of justice.My reader, I know that you will be the jury in this case. Most certainly you will be my judge. Why did I do it? Because I couldn’t help myself, of course. Because Anna stood before me so meekly, holding the front door invitingly open. Question: what do such innocents have in common? They never knew what hit them—casualties, all, of alethal convergence of apparently random currents, of an accumulation of old wrongs and hurts, not to mention old obsessions, gathering purpose in the fetid cockles of the human heart. A weal on tender skin. The cry of a child. In Anna’s case, a by now faded picture in a shilling book, many years ago. Enough; I can’t bear it. Enough. It is a shock to be here at last, in Asolo. What do the guidebooks say? "Town of a hundred horizons." "Renaissance gem of the Veneto." "Home of exiled royalty and poets." Originally home— did I dream the whole thing? No, the diary is lying here in front of me on Professor Ludovico Puppi’s writing table, torn but perfectly real—of my Madonna. It was naturally to Asolo, just a few miles north of Treviso, that I came when everything went belly-up at Mawle; can you see the connection? I had to run somewhere; I could no longer live with myself. Where better for the disappointed pilgrim-scholar to go? Home, then, yes. I admit that I was hoping for some sort of miracle; for a welcome, for redemption. Instead I merely found my own self lying in wait for me here, as the little shit always does. So what now? This is the 1st of September. Puppi, my host and former rival, is holidaying in Switzerland and cannot be reached. It’s bound to be a matter of mere days before he and Maddalena discover that I am here. They’ll try to squeeze the truth out of Anna. What will she tell or not tell them? How will I explain my ungainly flight from Mawle and my lubberly presence in Puppi’s palazzo a full five weeks before the start of the autumn vacanze for which I was invited? And worse still, how am I going to account for my sudden indifference to Bellini and all things connected with him? I am full of shame and pain. Asleep in bed at night I am troubled by dreams of a frightening delicacy and tenderness: an open sash window, a shadowed lake, a silver sandal, still bearing the impress of a woman’s foot, left out in the spluttering rain. I awoke this morning with a numbness cauterizing my left arm from shoulder to elbow, as if an invisible body had been pressing against it all night. The other, physical and more unsettling, change in me continues, occurring just as regularly as it did at Mawle. Once or twice a day, for no apparent reason, all six-foot-two of me, lean and red-haired, starts to shake. During these fits I imagine that the mesh of fine lines on my hands and arms begins to blur, and the contours of my limbs themselves to dissolve in an electric trembling, until I resemble an enormous insect, a large fly perhaps, the last of the summer flies, twitching itswings and rubbing its forelegs together. But then, when I peer into the mirror in Puppi’s bathroom (the large oval mirror, gilt-framed but not too ostentatious; although this is a palazzo it is, in spite of its ornate stuccoes, its marble stairway, its courtyard and well, its stables and barchessa, subdued and shabby), I see that I am after all still the same middle-aged man I was before the shaking started, T-bone of sternum and clavicles in place, my weak heart thud-thudding in its tented ribcage that still insists on rising and falling; my offending organ asleep, finally, in its bed of coirlike hair. The self-hatred I feel is never-ending. Artemisia, Puppi’s housekeeper, goes about with as much commotion as possible during the daytime, hauling pots and pans to the cortile to be scoured, and beating assorted rugs and pillowcases with a rattan whisk. The transistor radio which her son bought for her is on in the chilly mornings, through the hazy orange afternoons, into the chirruping dusk, belting out "Buongiorno Tristezza" (Buongiorno . . . tristezza! Oggi ho imparato che cosa è rimpianto, l’amaro rimpianto, l’eterno rimpianto . . .) and other hits about unattainable women by Claudio Villa. They send a battery of fiery darts straight into my heart. The boy appears at midday on his scooter, forks down a silent plate of macaroni in the kitchen, and disappears in a cloud of rattling red dust. Then I am fed. If I could just once cook my own food, dice a potato or peel a carrot, perhaps I would feel more like myself! But Artemisia has even the vegetal life of the villa under control. Too afraid of what I might say if I were to use the telephone, I have begun two letters to Anna, one apologetic and firmly regretful and the other apologetic and tender, but the monotonous beating of rugs, so much like the pounding of a human heart, and the crooning, and the dust, make me feel like a fool. All together it is, as my students would say, a bum deal. To be frank, I think the heat is getting to me. Slumped between waking and sleep in the mornings I think again of the nighta week ago when I crept upstairs to my old room at Mawle and saw Anna through the chink of her door, head averted and dressing gown partly unbuttoned, trying to pull the elastic band from her hair. A small porcelain lamp burning on the dressing table threw a shadow into each tired fold of her body. She must have been reading: an open magazine lay in the indentation on the bed. She did not hear me and as I could hardly bear to look at her I stared instead at her elbows moving vaguely in their loose sleeves. The August wind, more heat than air, blew through the branches of the elms outside and lifted the curtain, exposing a moon as thick as a cheese. She got up to close the window and I left. What can I say? She was radiant, heavy, impassable, and I waited for hours for the light under her door to go out so that Iwould not have to feel the weight of her wakeful presence across the corridor. Time passes very slowly here. Getting through it is no mean feat. I either crawl about the town, my heart shuddering in theheat, or sit inertly at my north-facing bedroom window, breathing in the cool slope of the Dolomites. More often—and since my stay at Mawle this has become my real occupation, one which I try to put off but always give in to—I do somepurposeful snooping. The palazzo is full of curious junk and old bric-a-brac: behind a sparse frontier population of sheeted winter coats and flaccid trousers every cupboard seems to conceal a secret interior life rich with yellowing suitcases, chipped flowerpots, cracked picture frames, skittering mothballs, and, most annoying of all, shoeboxes stuffed with tight-lipped family photographs and trite Puppi family correspondence. My darling Ludo, beware of the American, Lynch. That slippery fish knows everything, he knows about the existence of the Bellini and has even been sending me insinuating letters! Shall I invite him to Mawle in order to reel him in? Surely he can find the damn thing, if anyone can? Write soon to your anxious Maddalena, my big stud [stallone maschio mio]. No, I lie. I made that one up. There is no such vulgar and incriminating message in Signora Roper’s hand, just as there is no exact Italian equivalent for "my big stud." One afternoon I thought that I had at last found what I had been looking for. My wits weighed down as if with lead sinkers by Artemisia’s gnocchi margherita (potato dumplings, pulpy pomodoro, glittering green oil, a talcum spray of parmesan; you try it), prowling through the flagged rooms in search of something that would pull together the bizarre web of secrets into which I had so recently stumbled, I came across a low, dusty, glass-paneled bookshelf with a tasseled key, standing all on its own in a snug alcove. Here, surely, I would discover, among a stash of calf- and leather-bound volumes, a second diary or notebook—its thick coffee-colored pages crisp under my prehensile fingers—that would at last give me the full account of how my Madonna had arrived at Mawle in the possession of Anna’s great-grandfather James Roper; the frank story of his tragically brief marriage— every last detail! But in it I found nothing, nothing at all, except for a pile of curling National Geographics ("Lucy: the Real Eve? An Interview with Richard Leakey"), an old flower press of the kind constructed from blotting paper pinned down between wooden boards by metal screws—releasing, at a twist, a starry head of silver-haired edelweiss—and a first edition, with some of its furry pages still uncut, of Robert Browning’s last collection of poems, Asolando. On Sunday, three days ago, I left the house a little after midday to escape Artemisia’s pitying glances and strolled for anhour in the thin shade of the Foresto Vecchio. Across the rooftops the old clock tower of Catarina Cornaro’s castle stood white as a bone in the glare, its empty colonnades crowded with sunlight. The campanile of the cathedral tolled one slow saffron note: mass was long over, the throng dispersed. Behind Santa Maria a cramped piazzetta gave way to a row of stone steps, above which the faultless cornflower-bright sky unfurled its smooth banner of heat. The whole day, caught in a globe of pure color, seemed to proclaim its radical innocence. Even the trees on the horizon looked self-sufficient, their undersides gleaming as if stroked by a glazing brush, each tiny scalloped leaf outlined by a cloisonné shadow. I bounded up the steps into the main piazza of the town and there was the familiar lion with its left paw hooked over a shield, stone wings splayed stiffly in the windless air. I stood stock-still, sweating heavily. I recognized it at once. It was the very same lion as the one hidden in the overgrown rose garden at Mawle. At this distance the ruddy three-story brick front of the house seems shrunken, its ten slender pilasters, pedimented door,and Ionian bosses pathetically out of place, as if stuck on the face of an apple that has shriveled too long in the sun. There is no going back. All that is left to me now is self-imposed banishment from the one place where I have been happy. Perversely, patchily, but undeniably happy. I want to confess, to confess it all; and perhaps, if there is time—if I canbring myself to do it, if I have the courage—to say goodbye. Excerpted from The Bellini Madonna by Elizabeth Lowry.Copyright © 2008 by Elizabeth Lowry.Published in 2008 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC]. All rights reserved. This work is protected under copyright laws and reproduction is strictly prohibited. Permission to reproduce the material in any manner or medium must be secured from the Publisher.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherPicador

- Publication date2010

- ISBN 10 0312429665

- ISBN 13 9780312429669

- BindingPaperback

- Edition number1

- Number of pages368

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 64.00

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Bellini Madonna

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks3891

Buy New

US$ 64.00

Convert currency