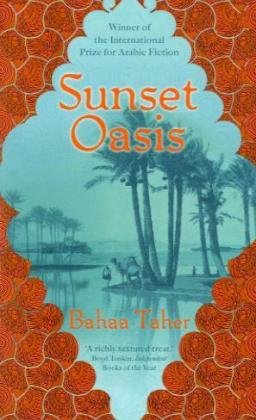

Items related to Sunset Oasis

Winner of the first â Arabic Booker Prize,â a vivid compelling historical tale set in late nineteenth-century Egypt.

When Mahmoud, a disgraced Egyptian officer, is posted to the remote desert town of Siwa, his Irish wife insists on accompanying him, to pursue the secrets of Alexander the Great. Neither is prepared for the stultifying heat, the hostility of the townspeople, or the astonishing and disturbing events that befall them in the dreamlike other-worldliness of the Sunset Oasis.

In turns mesmerizing and shocking, Sunset Oasis is an enthralling story of mystery and frustrated passions set against the backdrop of an exotic locale in the late 1800s.

When Mahmoud, a disgraced Egyptian officer, is posted to the remote desert town of Siwa, his Irish wife insists on accompanying him, to pursue the secrets of Alexander the Great. Neither is prepared for the stultifying heat, the hostility of the townspeople, or the astonishing and disturbing events that befall them in the dreamlike other-worldliness of the Sunset Oasis.

In turns mesmerizing and shocking, Sunset Oasis is an enthralling story of mystery and frustrated passions set against the backdrop of an exotic locale in the late 1800s.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

A widely read novelist in the Arab world, Egyptian Bahaa Taher has received honours and awards in Egypt and abroad, including the prestigious Italian Giuseppe Acerbi prize and, in 2008, the Booker Prize Foundation’s first International Prize for Arabic Fiction for Sunset Oasis.

From the Hardcover edition.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

From the Hardcover edition.

1

Mahmoud

He told me, 'Your wife is a brave woman,' as though I don't know my own wife! Isn't she willingly going into danger with me? All the same, it may be that I don't truly know Catherine. Not now! The important thing is it was no coincidence. Every word he utters is spoken for a reason, though Catherine isn't the problem at this moment. And anyway, I'll never solve any problem wandering the gloomy corridors of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, especially following that oppressive meeting with Mr Harvey.

There was nothing new in what he said, apart from the veiled hints, some of which I understood and the rest of which puzzled me.

I knew before I saw him that matters were settled. Brigadier General Saeed Bey had informed me that the ministry's advisor had forwarded the recommendation to His Excellency the Minister of Internal Affairs and His Excellency had issued a transfer order, to be implemented immediately. I had only a few days left if I was to join the caravan that departed from Kerdasa, and the brigadier general advised me, as a friend, to abandon the idea of taking my wife: the journey to the oasis was not easy, and the posting itself very difficult, as I well knew, though, in the end, the decision was mine; despite which, it was his duty to warn me of the danger of the journey, which, under the best conditions and with a skilful guide, took at least two weeks.

I'm confident that Saeed wasn't trying to scare me and I believe he did everything in his power to have me excused the posting. Our friendship is of long standing, though it may have waned over the years and these days is hardly more than the relationship between any official and his subordinate. However that may be, the stories and secrets of a bygone age form a bond. We haven't spoken of them for years, but each of us knows that the other still remembers. My other colleagues, of course, warned me, with suspect compassion, against the journey. Some were glad to have escaped the posting themselves and that it had fallen to me, and others had to make an effort to hide their delight at my discomfiture. They told me of the numerous caravans that had gone astray in the desert and been swallowed up by the sands, of small caravans that had lost the path and of a mighty Persian army on its way to take the oasis long ago that the desert had engulfed and buried beneath its sands for ever. They told me it was a lucky caravan which completed its journey before its supplies of water ran out and before the winds altered the features of the road, building dunes that had not existed before and burying the wells on which the caravans depended for watering the camels. Lucky too the caravan whose campsites were not attacked by wolves or hyenas and one or two of whose company were not stung by a scorpion or a snake.

All this was said, and more, but I paid no attention. My fear of the caravan's safe arrival at its destination is no less than my fear of its getting lost. I know very well I am going to the place where it is my destiny to be killed, and perhaps Catherine's too.

Was that one of the things Mr Harvey was hinting at in our meeting?

I had entered his office determined to provoke him. What did I have to lose?

It was the first time I had been in the office of this advisor, who held all the strings of the ministry in his hands. I found his diplomatic manner of talking affected and I found him affected too, as he sat there, his short body behind a huge desk, a tarboosh, from beneath which fair hair peeped, unconvincingly perched on his head. He didn't address himself to me but for most of the time directed his remarks towards an invisible point to his right, in the corner of the office. He repeated the things I had already heard from Brigadier General Saeed, but kept needling me on what he took to be my weak point: 'You must be happy, Captain Mahmoud Abd el Zahir Effendi – I beg your pardon, I should say Major Mahmoud now, of course!' he said, referring to my appointment as district commissioner for the oasis. He pretended to look through my service file, which was placed in front of him, and went on to say that under normal circumstances I would have had to wait long for this promotion.

I interrupted him with a smile, which I tried to make polite, to say, 'Especially if one takes into consideration, Mr Advisor, how few in the ministry would welcome such a promotion for themselves!'

He made no comment and didn't look at me. Instead, he turned the pages of the other file, on which 'Siwa Oasis' was written in large letters in English. He seemed to be enjoying what he was reading and muttered 'Interesting, very interesting' to himself every now and then. Finally, raising his face towards me with something like a smile on his lips, he said, 'So you know, my dear Major Mahmoud, that you will deal only with the heads of the families, whom in the oasis they call the agwad?'

'Naturally. Saeed Bey has given me all the necessary instructions.'

He went on, as though I hadn't spoken, to tell me that I was to have no dealings with the cultivators whom . . . and here he returned to the file in search of them and I reminded him that they were called zaggala.

Taking another quick look at the file, he echoed, 'Yes, yes. The zaggala. So long as they accept such a way of doing things, what business is it of ours? One is reminded somewhat of Sparta. Have you heard of Sparta, in ancient Greece, Mr Abd el Zahir?'

'I have heard of it, Mr Harvey.'

A certain disappointment appeared on his face at the thought of my having heard of Sparta, but he was determined to continue his lecture. 'Yes, indeed. Sparta. With a difference, of course! Sparta was a city dedicated to the production of warriors. They trained their children from infancy to become soldiers and they kept them apart from the residents of the city, which is how the whole of Sparta came to be an army living in a city, the strongest city in all Greece until Alexander appeared. And these, uh . . . these zaggala in the oasis are also conscripted, to work the land until they are forty years old. Forbidden to marry or to enter the city and pass through its walls after sunset.' Speaking for himself, he thought this was a system for society and for labour that deserved consideration; he might even go so far as to say it deserved admiration. 'Observe, Mr Zahir, our colonies in Africa and Asia where chaos reigns because labour there—'

I interrupted him once again with a laugh and said, 'My dear Mr Harvey, we don't have colonies in Africa, or Asia.'

I managed, however, to prevent myself from saying, 'We're the colonized!'

He frowned for a moment, abandoned his musings on the matter of the colonies, and returned to his perusal of the file. Then he raised his head and gave me a sudden, crafty smile as he said, 'Naturally, the other aspects of this system of theirs that separates the men from the women in boyhood do not concern us. It is a matter of no interest to us. We have nothing to do with their primitive customs.'

I understood what he was trying to say but did not respond, so he started addressing the invisible thing to his right again. I would have heard, of course, from Saeed Bey, that they were divided there into two hostile clans.

My patience was close to exhausted. Yes, yes, and I knew that the battles between them were never ending.

He turned his face towards me once more and emphasized his words as he said, 'Even this is no concern of ours. These battles are a part of their lives and they are free to do what they like with themselves, unless, of course, it should be possible, through specific alliances with one clan or another, to turn this into a means to assure our domination. It is a tried and true method, so long as the alliance with one party does not go on too long. The alliance has to be with one group this time and with their opponents the next. Do you understand?'

'I am doing my best, Your Excellency. I am aware of the policy, but have no experience of its application.'

'You will learn, my dear sir,' he said, with, for the first time, a certain malice. 'Do not forget that your first task will be to collect the taxes. A difficult task, as you are aware. A very difficult task. Your survival instinct will teach you this, and other policies, Major.'

He stopped suddenly and smiled again as he said, 'There is, all the same, something comical about the whole business. These people built themselves a fortress in the desert and built a town inside the fortress to protect themselves from the raids of the Bedouin, and despite this, the blood that the Bedouin would have shed in the open they have taken upon themselves to spill behind their own walls.' He found this quite remarkable. He found it extremely oriental!

The blood rose to my face and I burst out, 'Battles like these, within one group of people, are to be found in both East and West, Mr Harvey. It's different from invasion from the outside . . .'

He looked at my face for a while and then said, in an amused tone, 'Major Mahmoud Effendi is still under the influence of ideas from the past. Though, of course, he no longer sympathizes with the mutineers?'

I was incapable of controlling myself and burst out once more, 'I never sympathized with any mutineer. I was performing my duty and nothing more, and I have paid the price twice over in unjust treatment.'

He shook his head. Anyway, I would be aware, naturally, he pointed out, that my work would be the object of close scrutiny.

I thought this would be my last chance, so I said, in a tone of voice I tried to keep perfectly neutral, 'I hope that my work, when scrutinized, will be found satisfactory. But what if I do not succeed?'

He replied curtly, 'You know that you will pay the price.'

Then he caught himself, as though he had read my thoughts, and said, 'In any case, the penalty will not be your return to Cairo.'

Suddenly he changed the subject. I had to know that Saeed Bey objected to my taking my lady wife with me. Out of concern for her safety, of course. He had, however, informed His Excellency that the ministry did not interfere in the private lives of officers. Moreover, the lady was, he believed . . .

He paused for a moment and appeared to hesitate over his choice of words before continuing, 'The lady is a brave woman.' Then he repeated this, shaking his head. 'Indeed. A brave woman.'

I said nothing and he stood up suddenly. I stood too and he started talking to me in an official tone: 'You will travel with the Kerdasa caravan since it is ready to depart but I will send a number of horses' (and here the ghost of a smile appeared on his lips) 'which I hope will reach their destination alive, with the Matrouh caravan, which leaves in about two weeks.'

'Beaten by the British again!' I said to myself as I left his office. 'How I hate you, Mr Harvey. How I hate you all, along with this ministry. But there's no escape.'

I have to go home now and prepare for the journey. But what is there left to get ready? As soon as I told her that all efforts to excuse me from the posting had failed, Catherine gathered together everything we would need, and collected from the bookshops every book that discusses the oasis or in which mention of it occurs. She has left nothing to chance. Yesterday she told me of her remarkable plan to combat the bites of scorpions and snakes, so I referred her to a Rifa'I sheikh and convinced her that he had greater experience in dealing with poisons. She too, then, is afraid of such things – so what is the secret of her enthusiasm for this journey? I have made every attempt to convince her to stay, but to no effect. She knows the dangers awaiting me there but doesn't care. If I were naive, I'd say the reason was love, and that she didn't want her husband to perish alone. I do believe she loves me, but not that much!

I left the ministry, crossed el Dawaween Street, and proceeded until I reached Abdeen police station. In this station my whole life has been fashioned, and wasted, at a short distance from the only house I have ever known. It never occurred to me as a child, though, that I should end up doing such work.

Anyway, the time for regret is past. What do I have to regret? And what did I hope for when I was a boy? I gave no thought to the future. All I wanted was for things to go on the way they were. A happy childhood and a happier boyhood. My father denied me and my younger brother nothing. He forbade us no pleasure and never forced us to pay attention to our education or have done with it within a suitable period. My brother Suleiman liked to spend most of his time with my father at his shop in el Muski, learning the basics of the trade. For me, there was nothing to sully the bright days of my life. It was the last days of Khedive Ismail, the whole city was in commotion, and I dawdled away my time at the grammar school until I was almost twenty. I knew women and I kept company with slave girls and I spent my nights with friends moving from one café and bar to another. At our large house in Abdeen, there was always a feast being held and scarcely a night went by without guests, a party, and the most renowned singers, male and female. Thursday nights were the exception. On Thursday, the servants would remove all the furniture from the large room on the first storey, cover the floor with carpets, perfume the place with incense, and place brass pots filled with rose-scented water in the corners. That was the night of the 'People of the Way', of songs of praise for the Prophet, and of the circles of remembrance of God in favour of which my father, and I along with him, would abandon all other pleasures. I would chant with the chanters and sway with the participants in the dhikr till I was bathed in sweat and my limbs exhausted, and then a calm, deep sleep would come that lasted all night. And in the morning, I would go early with my father and Suleiman to Friday prayer at the mosque of el Hussein. The same night, however, the cycle would begin again, until, one evening, I found myself by chance with my friends at the Matatia Café on Ataba Square. There I beheld that turbaned man who spoke Arabic like a Turk, or a Syrian. I had never before heard the like of what he had to say, or perhaps I had but had paid no attention. Nevertheless, the words of Sheikh el Afghani and the enthusiasm of the disciples around him forced me to listen and pay attention, and thus I became addicted, in addition to wine and women, to the gatherings of the sheikh and the reading of the newspapers edited by his disciples – Misr, and el Tigara, and el Lata'if. Whenever the Khedive had one of them closed down, I would transfer to another, new one that would repeat what its sequestrated sister journal had said, all of them attacking the rulers who had plunged Egypt into debt and brought it to bankruptcy, and all of them burning with anger at the domin...

Mahmoud

He told me, 'Your wife is a brave woman,' as though I don't know my own wife! Isn't she willingly going into danger with me? All the same, it may be that I don't truly know Catherine. Not now! The important thing is it was no coincidence. Every word he utters is spoken for a reason, though Catherine isn't the problem at this moment. And anyway, I'll never solve any problem wandering the gloomy corridors of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, especially following that oppressive meeting with Mr Harvey.

There was nothing new in what he said, apart from the veiled hints, some of which I understood and the rest of which puzzled me.

I knew before I saw him that matters were settled. Brigadier General Saeed Bey had informed me that the ministry's advisor had forwarded the recommendation to His Excellency the Minister of Internal Affairs and His Excellency had issued a transfer order, to be implemented immediately. I had only a few days left if I was to join the caravan that departed from Kerdasa, and the brigadier general advised me, as a friend, to abandon the idea of taking my wife: the journey to the oasis was not easy, and the posting itself very difficult, as I well knew, though, in the end, the decision was mine; despite which, it was his duty to warn me of the danger of the journey, which, under the best conditions and with a skilful guide, took at least two weeks.

I'm confident that Saeed wasn't trying to scare me and I believe he did everything in his power to have me excused the posting. Our friendship is of long standing, though it may have waned over the years and these days is hardly more than the relationship between any official and his subordinate. However that may be, the stories and secrets of a bygone age form a bond. We haven't spoken of them for years, but each of us knows that the other still remembers. My other colleagues, of course, warned me, with suspect compassion, against the journey. Some were glad to have escaped the posting themselves and that it had fallen to me, and others had to make an effort to hide their delight at my discomfiture. They told me of the numerous caravans that had gone astray in the desert and been swallowed up by the sands, of small caravans that had lost the path and of a mighty Persian army on its way to take the oasis long ago that the desert had engulfed and buried beneath its sands for ever. They told me it was a lucky caravan which completed its journey before its supplies of water ran out and before the winds altered the features of the road, building dunes that had not existed before and burying the wells on which the caravans depended for watering the camels. Lucky too the caravan whose campsites were not attacked by wolves or hyenas and one or two of whose company were not stung by a scorpion or a snake.

All this was said, and more, but I paid no attention. My fear of the caravan's safe arrival at its destination is no less than my fear of its getting lost. I know very well I am going to the place where it is my destiny to be killed, and perhaps Catherine's too.

Was that one of the things Mr Harvey was hinting at in our meeting?

I had entered his office determined to provoke him. What did I have to lose?

It was the first time I had been in the office of this advisor, who held all the strings of the ministry in his hands. I found his diplomatic manner of talking affected and I found him affected too, as he sat there, his short body behind a huge desk, a tarboosh, from beneath which fair hair peeped, unconvincingly perched on his head. He didn't address himself to me but for most of the time directed his remarks towards an invisible point to his right, in the corner of the office. He repeated the things I had already heard from Brigadier General Saeed, but kept needling me on what he took to be my weak point: 'You must be happy, Captain Mahmoud Abd el Zahir Effendi – I beg your pardon, I should say Major Mahmoud now, of course!' he said, referring to my appointment as district commissioner for the oasis. He pretended to look through my service file, which was placed in front of him, and went on to say that under normal circumstances I would have had to wait long for this promotion.

I interrupted him with a smile, which I tried to make polite, to say, 'Especially if one takes into consideration, Mr Advisor, how few in the ministry would welcome such a promotion for themselves!'

He made no comment and didn't look at me. Instead, he turned the pages of the other file, on which 'Siwa Oasis' was written in large letters in English. He seemed to be enjoying what he was reading and muttered 'Interesting, very interesting' to himself every now and then. Finally, raising his face towards me with something like a smile on his lips, he said, 'So you know, my dear Major Mahmoud, that you will deal only with the heads of the families, whom in the oasis they call the agwad?'

'Naturally. Saeed Bey has given me all the necessary instructions.'

He went on, as though I hadn't spoken, to tell me that I was to have no dealings with the cultivators whom . . . and here he returned to the file in search of them and I reminded him that they were called zaggala.

Taking another quick look at the file, he echoed, 'Yes, yes. The zaggala. So long as they accept such a way of doing things, what business is it of ours? One is reminded somewhat of Sparta. Have you heard of Sparta, in ancient Greece, Mr Abd el Zahir?'

'I have heard of it, Mr Harvey.'

A certain disappointment appeared on his face at the thought of my having heard of Sparta, but he was determined to continue his lecture. 'Yes, indeed. Sparta. With a difference, of course! Sparta was a city dedicated to the production of warriors. They trained their children from infancy to become soldiers and they kept them apart from the residents of the city, which is how the whole of Sparta came to be an army living in a city, the strongest city in all Greece until Alexander appeared. And these, uh . . . these zaggala in the oasis are also conscripted, to work the land until they are forty years old. Forbidden to marry or to enter the city and pass through its walls after sunset.' Speaking for himself, he thought this was a system for society and for labour that deserved consideration; he might even go so far as to say it deserved admiration. 'Observe, Mr Zahir, our colonies in Africa and Asia where chaos reigns because labour there—'

I interrupted him once again with a laugh and said, 'My dear Mr Harvey, we don't have colonies in Africa, or Asia.'

I managed, however, to prevent myself from saying, 'We're the colonized!'

He frowned for a moment, abandoned his musings on the matter of the colonies, and returned to his perusal of the file. Then he raised his head and gave me a sudden, crafty smile as he said, 'Naturally, the other aspects of this system of theirs that separates the men from the women in boyhood do not concern us. It is a matter of no interest to us. We have nothing to do with their primitive customs.'

I understood what he was trying to say but did not respond, so he started addressing the invisible thing to his right again. I would have heard, of course, from Saeed Bey, that they were divided there into two hostile clans.

My patience was close to exhausted. Yes, yes, and I knew that the battles between them were never ending.

He turned his face towards me once more and emphasized his words as he said, 'Even this is no concern of ours. These battles are a part of their lives and they are free to do what they like with themselves, unless, of course, it should be possible, through specific alliances with one clan or another, to turn this into a means to assure our domination. It is a tried and true method, so long as the alliance with one party does not go on too long. The alliance has to be with one group this time and with their opponents the next. Do you understand?'

'I am doing my best, Your Excellency. I am aware of the policy, but have no experience of its application.'

'You will learn, my dear sir,' he said, with, for the first time, a certain malice. 'Do not forget that your first task will be to collect the taxes. A difficult task, as you are aware. A very difficult task. Your survival instinct will teach you this, and other policies, Major.'

He stopped suddenly and smiled again as he said, 'There is, all the same, something comical about the whole business. These people built themselves a fortress in the desert and built a town inside the fortress to protect themselves from the raids of the Bedouin, and despite this, the blood that the Bedouin would have shed in the open they have taken upon themselves to spill behind their own walls.' He found this quite remarkable. He found it extremely oriental!

The blood rose to my face and I burst out, 'Battles like these, within one group of people, are to be found in both East and West, Mr Harvey. It's different from invasion from the outside . . .'

He looked at my face for a while and then said, in an amused tone, 'Major Mahmoud Effendi is still under the influence of ideas from the past. Though, of course, he no longer sympathizes with the mutineers?'

I was incapable of controlling myself and burst out once more, 'I never sympathized with any mutineer. I was performing my duty and nothing more, and I have paid the price twice over in unjust treatment.'

He shook his head. Anyway, I would be aware, naturally, he pointed out, that my work would be the object of close scrutiny.

I thought this would be my last chance, so I said, in a tone of voice I tried to keep perfectly neutral, 'I hope that my work, when scrutinized, will be found satisfactory. But what if I do not succeed?'

He replied curtly, 'You know that you will pay the price.'

Then he caught himself, as though he had read my thoughts, and said, 'In any case, the penalty will not be your return to Cairo.'

Suddenly he changed the subject. I had to know that Saeed Bey objected to my taking my lady wife with me. Out of concern for her safety, of course. He had, however, informed His Excellency that the ministry did not interfere in the private lives of officers. Moreover, the lady was, he believed . . .

He paused for a moment and appeared to hesitate over his choice of words before continuing, 'The lady is a brave woman.' Then he repeated this, shaking his head. 'Indeed. A brave woman.'

I said nothing and he stood up suddenly. I stood too and he started talking to me in an official tone: 'You will travel with the Kerdasa caravan since it is ready to depart but I will send a number of horses' (and here the ghost of a smile appeared on his lips) 'which I hope will reach their destination alive, with the Matrouh caravan, which leaves in about two weeks.'

'Beaten by the British again!' I said to myself as I left his office. 'How I hate you, Mr Harvey. How I hate you all, along with this ministry. But there's no escape.'

I have to go home now and prepare for the journey. But what is there left to get ready? As soon as I told her that all efforts to excuse me from the posting had failed, Catherine gathered together everything we would need, and collected from the bookshops every book that discusses the oasis or in which mention of it occurs. She has left nothing to chance. Yesterday she told me of her remarkable plan to combat the bites of scorpions and snakes, so I referred her to a Rifa'I sheikh and convinced her that he had greater experience in dealing with poisons. She too, then, is afraid of such things – so what is the secret of her enthusiasm for this journey? I have made every attempt to convince her to stay, but to no effect. She knows the dangers awaiting me there but doesn't care. If I were naive, I'd say the reason was love, and that she didn't want her husband to perish alone. I do believe she loves me, but not that much!

I left the ministry, crossed el Dawaween Street, and proceeded until I reached Abdeen police station. In this station my whole life has been fashioned, and wasted, at a short distance from the only house I have ever known. It never occurred to me as a child, though, that I should end up doing such work.

Anyway, the time for regret is past. What do I have to regret? And what did I hope for when I was a boy? I gave no thought to the future. All I wanted was for things to go on the way they were. A happy childhood and a happier boyhood. My father denied me and my younger brother nothing. He forbade us no pleasure and never forced us to pay attention to our education or have done with it within a suitable period. My brother Suleiman liked to spend most of his time with my father at his shop in el Muski, learning the basics of the trade. For me, there was nothing to sully the bright days of my life. It was the last days of Khedive Ismail, the whole city was in commotion, and I dawdled away my time at the grammar school until I was almost twenty. I knew women and I kept company with slave girls and I spent my nights with friends moving from one café and bar to another. At our large house in Abdeen, there was always a feast being held and scarcely a night went by without guests, a party, and the most renowned singers, male and female. Thursday nights were the exception. On Thursday, the servants would remove all the furniture from the large room on the first storey, cover the floor with carpets, perfume the place with incense, and place brass pots filled with rose-scented water in the corners. That was the night of the 'People of the Way', of songs of praise for the Prophet, and of the circles of remembrance of God in favour of which my father, and I along with him, would abandon all other pleasures. I would chant with the chanters and sway with the participants in the dhikr till I was bathed in sweat and my limbs exhausted, and then a calm, deep sleep would come that lasted all night. And in the morning, I would go early with my father and Suleiman to Friday prayer at the mosque of el Hussein. The same night, however, the cycle would begin again, until, one evening, I found myself by chance with my friends at the Matatia Café on Ataba Square. There I beheld that turbaned man who spoke Arabic like a Turk, or a Syrian. I had never before heard the like of what he had to say, or perhaps I had but had paid no attention. Nevertheless, the words of Sheikh el Afghani and the enthusiasm of the disciples around him forced me to listen and pay attention, and thus I became addicted, in addition to wine and women, to the gatherings of the sheikh and the reading of the newspapers edited by his disciples – Misr, and el Tigara, and el Lata'if. Whenever the Khedive had one of them closed down, I would transfer to another, new one that would repeat what its sequestrated sister journal had said, all of them attacking the rulers who had plunged Egypt into debt and brought it to bankruptcy, and all of them burning with anger at the domin...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHodder Ome

- Publication date2000

- ISBN 10 0340998601

- ISBN 13 9780340998601

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages320

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 93.73

Shipping:

US$ 4.25

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Sunset Oasis

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0340998601

Buy New

US$ 93.73

Convert currency

Sunset Oasis

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0340998601

Buy New

US$ 97.31

Convert currency

Sunset Oasis

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Paperback. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # VIB0340998601

Buy New

US$ 103.07

Convert currency