Items related to The World in a City: Traveling the Globe Through the...

–from the Preface

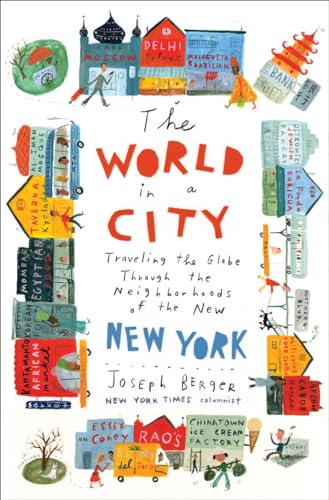

Fifty years ago, New York City had only a handful of ethnic groups. Today, the whole world can be found within the city’s five boroughs–and celebrated New York Times reporter Joseph Berger sets out to discover it, bringing alive the sights, smells, tastes, and people of the globe while taking readers on an intimate tour of the world’s most cosmopolitan city.

For urban enthusiasts and armchair explorers alike, The World in a City is a look at today’s polyglot and polychrome, cosmopolitan and culturally rich New York and the lessons it holds for the rest of the United States as immigration changes the face of the nation. With three out of five of the city’s residents either foreign-born or second-generation Americans, New York has become more than ever a collection of villages–virtually self-reliant hamlets, each exquisitely textured by its particular ethnicities, history, and politics. For the price of a subway ride, you can visit Ghana, the Philippines, Ecuador, Uzbekistan, and Bangladesh.

As Berger shows us in this absorbing and enlightening tour, New York is an endlessly fascinating crossroads. Naturally, tears exist in this colorful social fabric: the controversy over Korean-language shop signs in tony Douglaston, Queens; the uneasy proximity of traditional cottages and new McMansions built by recently arrived Russian residents of Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn. Yet in spite of the tensions among neighbors, what Berger has found most miraculous about New York is how the city and its more than eight million denizens can adapt to–and even embrace–change like no other place on earth, from the former pushcart knish vendor on the Lower East Side who now caters to his customers via the Internet, to the recent émigrés from former Soviet republics to Brooklyn’s Brighton Beach and Midwood whose arrival saved New York’s furrier trade from certain extinction.

Like the place it chronicles, The World in a City is an engaging hybrid. Blending elements of sociology, pop culture, and travel writing, this is the rare book that enlightens readers while imbuing them with the hope that even in this increasingly fractious and polarized world, we can indeed co-exist in harmony.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

So You Thought You Knew Astoria

...

For half a century, Astoria in Queens has been a neighborhood of cafés where dark-haired Greek men sip strong coffee and smoke strong cigarettes while talking in Greek late into the night. It is a place of quiet sidewalks lined with tenderly fussed-over brick and shingle row houses, where a solitary widow in black can be glimpsed scurrying homeward as if she were on the island of Rhodes.

The cafés are still teeming, the houses tidy. But the Greek hold on the neighborhood has slowly been weakening. Successful Greeks have been leaving for leafier locales. As a result, there are moments when Astoria has a theme-park feel to it, a cardboard façade of a Greek Main Street with cafés named Athens, Omonia, and Zodiac and Greece’s blue and white colors splashed everywhere, but a diminishing number of actual Greeks living within.

That’s because other groups have been rising up to take their place. On a Friday on Steinway Street, one of Astoria’s commercial spines, several hundred men from North African and Middle Eastern countries were jammed into Al-Iman Mosque, a marble-faced storefront that is one of several Muslim halls of worship that have sprung up in Astoria. Some wore ordinary street clothes, some white robes and knit white skullcaps. There were so many worshipers that thirteen had to pray on the sidewalk, kneeling shoeless on prayer mats and touching their foreheads and palms to the ground. When the prayers were over, El Allel Dahli, a Moroccan immigrant, emerged with his teenage son, Omar, telling of the plate of couscous and lamb he had brought as a gift to the poor to honor the birth that morning of his daughter, Jenine. “I am very happy today,” he told me.

He could also have been happy that, as his visit confirmed, the immediate neighborhood was turning into New York City’s casbah. Not only was there his flourishing mosque, but down Steinway Street, as far as his eyes could see, there were Middle Eastern restaurants, groceries, travel agencies, a driving school, a barber shop, a pharmacy, a dried fruit and nuts store, a bookstore—twenty-five shops in all. In the cafés,

clusters of Egyptian, Moroccan, or Tunisian men were puffing on hookahs—tall, gaudily embellished water pipes stoked with charcoal to burn sheeshah, the fragrant tobacco that comes in flavors such as molasses and apple. Sometimes these men—taxi drivers, merchants, or just plain idlers—play backgammon or dominoes or watch Arabic television shows beamed in by satellite, but mostly they schmooze about the things Mediterranean men talk about when they’re together— soccer, politics, women—while waiters fill up their pipes with chunks of charcoal at $4 a smoke. In classic New York fashion, Steinway Street is a slice of Arabic Algiers on Astoria’s former Main Street, renamed after a German immigrant who a century before assembled the world’s greatest pianos a few blocks away.

And it is not just Middle Easterners and North Africans who are changing the neighborhood’s personality. Those settling in Astoria in the past decade or two include Bangladeshis, Serbians, Bosnians, Ecuadorians, and, yes, even increasingly young Manhattan professionals drawn by the neighborhood’s modest rents, cosmopolitan flavors, and short commute to midtown Manhattan. More vibrant than them all seem to be the Brazilians, who have brought samba nightclubs and bikini-waxing salons to streets that once held moussaka joints. When Brazil won the World Cup in 2002, Astoria’s streets were turned into an all-night party, and when the team lost in 2006, the streets were leaden with mourning.

New York can be viewed as an archipelago, like Indonesia a collection of distinctive islands, in its case its villagelike neighborhoods. Each island has its own way of doing things, its own flavor, fragrance, and indelible characters. But, as a result of the roiling tides of migration and the unquenchable human restlessness and hunger for something better and grander, most of these neighborhoods are in constant, ineluctable flux. Some transform with astonishing swiftness as if hit by a flood; a few suffer erosion that is scarcely detectable until one day its inhabitants realize that what was there is gone.

Astoria was an appropriate jumping-off point for my three-year-long ramble around the city because it is a classic New York neighborhood, a place that has long had a sharply defined character and a distinct place in the city’s landscape, but one that has been turned into a Babel of cultures by the waves of immigration set off by the 1965 law. When New Yorkers dropped the name Astoria, it was understood they were talking about an enclave where Greek was spoken and Greek folkways were observed. So it was striking to me as I walked the streets how much of that accent had faded. Astoria’s Greek population has been cut by a third in the past two decades, by some unofficial estimates, to 30,000 from 45,000, with official, if undercounted, census figures even gloomier, putting the number of people who claimed Greek ancestry at just 18,217, or 8.6 percent of the neighborhood’s residents.

The decline of the Greeks can be seen as an old New York story, no different from the shrinking of the Jewish population on the Lower East Side or the number of Italians along Arthur Avenue in the Bronx. As immigrants of one nationality make it, they forsake the jostling streets, and newer immigrants, hoping to make their fortunes, move in. “It’s an upward mobility kind of thing,” said Robert Stephanopoulos, dean of Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Cathedral on East Seventy-fourth Street and father of George (Bill Clinton’s press secretary and now an ABC broadcaster). But the fact that it is an oft- told story is scant consolation for longtime Greek residents who have tried to rekindle the old country in this new one. They find a bittersweet quality to the changeover. On the one hand, it affirms their community’s upswing; on the other, their village in New York is withering.

“In New York everything turns around,” Peter Figetakis, forty-eight, a Greek-born film director who has lived in Astoria since the 1970s, told me. “Now the Hindus and Arabs, it’s their time.”

For the newer residents, the mood is expansive. On a two-block stretch of Steinway between Twenty-eighth Avenue and Astoria Boulevard, there is a veritable souk, with shops selling halal meat, Syrian pastries, airplane tickets to Morocco, driving lessons in Arabic, Korans and other Muslim books, and robes in styles such as the caftan, the abaya, the hooded djellaba, and the chador, which covers the body from head to toe, including much of the face. Indeed, a common street sight is a woman in ankle-length robe and head scarf— hijab—surrounded by small children. Laziza of New York Pastry, a Jordanian bakery, may have baklava superior to that made by the neighborhood’s Greeks. With two dozen such Arabic shops, the Steinway strip outpaces the city’s most famous Middle Eastern thoroughfare, Brooklyn’s Atlantic Avenue, which was started by Lebanese and Syrian Christians, not Muslims. In cafés and restaurants once owned by Greeks and Italians, television shows from Cairo and news from Qatar- based Al Jazeera are beamed in on flat-screen televisions. Some cafés are open round-the-clock so taxi drivers can stop in and have their sheeshah and an espresso.

Noureddine Daouaou, a taxi driver from Casablanca who has lived in the United States for more than twenty years, said he prefers Astoria to other places in New York where Arabs cluster because the neighborhood has a cosmopolitan mix of peoples. “You don’t feel homesick,” he said. “You find peace somehow. You find people try to get along. We can understand each other in one language.”

The number of Arab speakers in the neighborhood the city designates as Queens Community Board 1 (the city is broken into fifty-nine community boards that offer advice on land-use and budget issues) rose from 2,265 in 1990 to 4,097 in 2000, an 80 percent increase, and will be far larger in the next census. For the Middle Easterners, the attraction to Astoria seems to be the congenial Mediterranean accent: foods that overlap with such Greek delicacies as kebab, okra, lentils, and honey-coated pastries, and cultural harmonies such as men idling with one another in cafés. “They feel more comfortable with Greeks,” George Mohamed Oumous, a forty-five-year-old Moroccan computer programmer, said of his fellow Arabs. “We’ve been near each other for centuries. You listen to Greek music, you think you could be listening to Egyptian music.”

Ali El Sayed, who is Steinway’s Sidney Greenstreet, the man aware of this mini-Casablanca’s secrets, was a pioneer. A broad-shouldered Alexandrian with a shaved head like a genie, Sayed moved to Steinway Street in the late 1980s to open the Kabab Café, a narrow six-table cranny filled with Egyptian bric-a-brac, stained glass, and a hookah or two. It sells a tasty hummus and falafel plate. “How’s the food, folks?” he’ll sometimes ask, displaying his American slang. “I’m just an insecure guy, so I need to ask.” He found Astoria congenial because it was easy to shop for foods, such as hummus and okra, that he uses in his cooking. Within a few years the neighborhood had enough Arabs and other Muslims to support its first mosque, which was opened in a onetime pool hall on Twenty-eighth Avenue.

Sayed told me that Egyptians in Astoria are proud to be Americans, proud to blend into American society. Indeed, Egyptians and other Arabs and Muslims are assimilating in the United States with as much enthusiasm as earlier immigrant groups. In London, Paris, and Hamburg, there is far more ambivalence. Even two and three generations after they began settling in those cities, the Muslim underclass tends to remain outside the mainstream, whether by choice or because of the hostility they encounter from their long-rooted European neighbors. In the aftermath of the September 11 attacks, those communities have been fertile soil for homegrown terrorists. But in American cities such as New York, Muslims have been “pretty much immune to the jihadist virus,” according to an assessment by Daniel Benjamin, a former National Security Council official quoted in The Atlantic on the fifth anniversary of September 11. Across the United States, Arab immigrants have a median income higher than the overall American one and a larger proportion of graduate degrees, something that is not true in France, Germany, and Britain. Moreover, Arabs and other Muslims are pouring into the United States in larger numbers than ever, despite the dip in the first years after 9/11, searching for jobs and personal freedom just as immigrants have always done. In 2005, for example, there were almost 5,000 Egyptians admitted as legal permanent residents, more than in the years before 9/11.

But assimilation can be a Trojan horse, a gift full of dangers, and those perils are appreciated in Arab Astoria. Many of the neighborhood’s Egyptians and other younger Middle Easterners are marrying non–Middle Easterners. Sayed is married to an Argentinian, and his seven-year-old son, Esmaeel, speaks English and Spanish, not Arabic. “There are lots of fears that their culture is getting destroyed,” Sayed said.

Though in many patches of Astoria, Arabs are supplanting Greeks, the transition, by most accounts, has been without overt bitterness or conflict. George Delis, district manager of Community Board 1, said, “I get complaints from Greeks that the streets are dirtier, the properties not as well kept. I say to them, ‘When you came to this country, the Italians and Irish were saying there goes the neighborhood.’ And that’s how I feel. This is a community of immigrants.” Indeed, Oumous, the Moroccan computer programmer, said there was some suspiciousness after September 11 and landlords were likely to inquire more scrupulously into newcomers’ backgrounds, but generally there has been no antagonism.

i heard an entirely different beat just ten blocks south—the samba sound of the Brazilians. The Brazilians stand out in the smorgasbord of New York Latinos, who generally come here poor, half educated, and willing to spirit across borders. Brazilians in New York more often tend to come from bourgeois backgrounds; they are well schooled, and many held professional, managerial, or highly skilled jobs before they left their homeland. The 2000 census revealed that 30.8 percent of the city’s Brazilians had degrees from colleges or graduate schools, triple the number for some other nationalities from Latin America, such as Mexicans or Ecuadorians. Brazilians can afford to fly here legally on tourist visas, which require proof of jobs and savings accounts, then intentionally overstay them. Unable to transfer their credentials here, they work as housekeepers, shoeshine guys, go-go dancers, and limousine drivers, hoping to legalize themselves but knowing that in the meantime they will make far more money here than they could have as white-collar workers in Brazil.

“In Brazil you have quality of life, but here you have financial security,” explained Jamiel Ramalho de Almeida, the neatly bearded owner of the Ipanema Beauty Salon on Thirty-sixth Avenue who holds a teaching degree from a Brazilian college. “When you get a taste of the good life, it’s hard to go back to what you had before.”

At least since Carmen Miranda, with a fruit bowl for a hat, chica- chica-boomed audiences out of some of their stodginess, Brazil has had a distinct mystique among Americans. Samba and bossa nova rhythms have shaped the music of Frank Sinatra and Manhattan’s dance clubs. Movies such as Black Orpheus, with its alternately haunting, rollicking score, and Dona Flor and Her Two Husbands, with its antic story of the erotic pull of a dead husband for a remarried widow, have mixed magic, lust, and a Brazilian love of revelry to relax American restraints. Pelé ignited a romance with soccer that has become a ritual of suburban autumn weekends.

But the mystique has always been felt at arm’s length. Very few Brazilians actually settled here. That has been changing. Brazil’s often inflationary economy and unemployment that perennially hovers near 10 percent have driven professionals and merchants to find their fortunes elsewhere. The New York area—not just Astoria, but Newark’s Ironbound and Danbury, Connecticut—has been a galvanic destination. Although the 2000 census counted 13,000 New York City residents of Brazilian ancestry, with 3,372 of them in Astoria, the Brazilian consulate thinks those are gross undercounts. José Alfredo Graça Lima, the consul general in New York, doubled those numbers, and Astoria officials believe there may be 15,000 Brazilians in the area.

So many, in fact, that Tatiana Pacheco told me, “I feel like I’m in a different Brazilian town instead of ten thousand miles away.” She is a slender twenty-eight-year-old woman with long brown hair who in many ways typifies the Brazilian New Yorker. She went to college in Brazil, then came here in the late 1990s and took a job as an au pair. By the time I met her she was working as a counselor to immigrants from all over the world, not just Brazil, at Immigration Advocacy Services, a nonprofit group near the mosque on Steinway Street.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherBallantine Books

- Publication date2007

- ISBN 10 0345487389

- ISBN 13 9780345487384

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages288

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 5.45

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The World in a City: Traveling the Globe Through the Neighborhoods of the New New York

Book Description hardcover. Condition: New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title!. Seller Inventory # 100-32881

The World in a City: Traveling the Globe Through the Neighborhoods of the New New York

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0345487389

The World in a City: Traveling the Globe Through the Neighborhoods of the New New York

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0345487389

The World in a City: Traveling the Globe Through the Neighborhoods of the New New York

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0345487389

The World in a City: Traveling the Globe Through the Neighborhoods of the New New York

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0345487389

The World in a City: Traveling the Globe Through the Neighborhoods of the New New York

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Brand New!. Seller Inventory # VIB0345487389

THE WORLD IN A CITY: TRAVELING T

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.15. Seller Inventory # Q-0345487389

The World in a City: Traveling the Globe Through the Neighborhoods of the New New York

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0345487389