Items related to The Four of Us: The Story of a Family

Synopsis

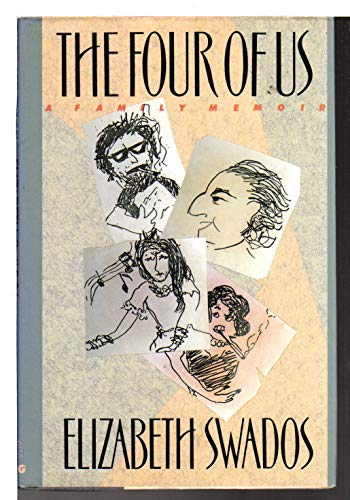

The moving story of the author's talented family, which is haunted by the tragedy of the first child's schizophrenia. Four essays, one for each family member's story, combine to create a complex and resonant picture of the four sides of a family rectangle.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

The Four of Us

The CartoonistWhen I was four my brother decided to teach me manners. He claimed to know Emily Post personally and he wanted to pass down to me the "L. J. Swados Interpretation" of her dos and don'ts. Lincoln was eleven and I believed he was a scholar. The lesson was strict and he didn't laugh. If I gasped or slurped, Lincoln glared at me through his thick fifties-style glasses."The question is, do you want to be a lady or a pig," he said to me. "A lady or a pig? Pigs can't find husbands with summer cottages on Lake Erie where brothers can come visit and go waterskiing." I tried to buckle down. Lincoln was eight years older than I. I tried to keep up to his standards. First I learned to sip my tomato soup soundlessly. This was hard, since Lincoln didn't want me to move the spoon. When I was nearly done he told me to drink the remaining soup from the opposite side of the bowl. This required that I lean over the bowl, tip it away from me, and lap at the soup with my tongue. My brother watched this carefully. Soup dribbled onto the tablecloth or down my chin. The ends of my long red hair dipped into the bowl. "You're really vying to become a spinster, you know that?" he said sadly. "No real man wants a woman who is incapable of drinking her soup upside down from a real china bowl. Mommy and Daddy will be so embarrassed. You'll have to marry an insurance salesman like Uncle Irving." He dabbed tenderly at the red splotches on my chin and collar. I tried not to cry. My crying infuriated him."The last lesson," Lincoln said to me, "is how to act gracefully if your napkin catches fire on the candelabrum and there's no butler with a fire extinguisher nearby." He lit all the candles on the Hanukkah menorah he'd brought out for our "formal dinner" and then set his paper napkin on fire. He watched the flames until they reached the tips of his long, grubby fingers."Lincoln," I cried. I was scared.At the last moment he shoved the burnt napkin in the crystal water glass. Sparks and smoke hissed up into the kitchen."Tra-la," my brother sang victoriously. "The idea is not to set your host's tablecloth or rug on fire. Now you try."I sat quietly, staring at the fuzzy particles of the burnt napkin floating in the darkened glass."No," I said. "Mommy'll get mad. I'm scared.""We're not talking about Mommy here," Lincoln said. "We're talking about Emily Post. I'm trying to teach you to become a lady."Even at four I knew that burning a napkin on a menorah had nothing to do with finding a rich husband."No," I whined."Stop whining!" my brother growled at me. "Whining, you little brat, can put you in the penitentiary of whiners. No one ever leaves there, they just whine themselves to death."He stood up, knocking over his chair as he did so, stalked to his room, and slammed the door. Soon I heard strains of Frank Sinatra coming from his record player. Lincoln sang along as he often did when he was comforting himself. He was out of tune--but he'd memorized the phrasing perfectly. Our live-in maid, Marie, returned from shopping and swiftly cleaned up the mess and me before my parents returned for dinner. I was ashamed at having let my brother down. Winning his forgiveness was a long and complicated task. I seemed destined to be the focus of his love, expectations, and experiments. I was also the one who constantly betrayed the very core of his hope. This responsibility was beyond my understanding, but I did nothingwithout thinking of his approval or severe disappointment. I was sure he could see me even in his dreams.

When I was five, he created treasure hunts for me which took me all over the house. The clues were often metaphorical and poetic and took me a long time to decipher. If a clue was hidden in the freezer the clue before it said, "Penguins dance here with their friends but humans have to watch their hands." Lincoln quickly grew impatient if I couldn't decipher his notes. He'd give me hints."Where are your Popsicles, Lizzie?" Think, for godsakes!Then we both dashed to the freezer and I'd find the next clue rolled around an ice cube.I got used to the fact that my brother's treasure hunts took me to the rooms in our new house that scared me and that he'd often leave me in a dark corner of the boiler room or the messy attic to find my way. If I whined or shouted his name, the treasure hunt was immediately called off. I'd once again become the object of my brother's scorn and silence for an undetermined period of punishment. If I trudged through to the end, the final prize was usually presented to me in the swampy lot behind our house, where no developments had yet been built. Lincoln dubbed it "Lincoln and Liz Forest," and in that magic place we were never allowed to fight or "think cruel thoughts." What a victory for me to find my brother waiting in the forest with my treasure. He handed me a surprise ball. A surprise ball was a ball made from long pieces of crepe paper layered and wound over each other. As I unwound each strip of crepe paper little prizes fell out. Rhinestone rings, miniature dolls. Miniature dishes and silverware. The center held the biggest prize of all ("just like an artichoke," Lincoln said). It was usually a necklace or bracelet which sparkled and appeared to be very valuable, though it inevitably turned my neck or wrist green."You are a princess," Lincoln often said to me. "You are my Princess Elizabeth sister."Lincoln's "Aunt Matilda" was one of his favorite games, but it did not always go well for me. I remember the winter of her first visit. The Buffalo snow was gray and sloshy. It went through my boots. I stood outside our house ringing and ringing the bell. The car wasn't in the driveway. Finally Lincoln let me in. "You have a visitor," he whispered. His glasses were crooked on his pointed nose. "But you're not properly dressed." He stripped me out of my snowsuit and boots. Then he nervously dressed me in a party dress he'd found in my closet."Mommy's gonna kill you," I remember telling him."Mothers don't kill their children in Buffalo," my brother said, "only in Greece."He tried to comb my hair and nearly pulled half of it out. I screamed as he tugged at the knots."Stop it!" he warned me. "Aunt Matilda will think you're nothing but a crybaby. She hates the tears of little girls. She says they kill plants and attract flies."I stopped crying. My socks were still wet. The gray snow from my snowsuit and boots melted onto the rug. I was scared. Lincoln was in a very happy mood. My nose was stopped up and I felt feverish, but he was too excited to notice.He pulled my grandmother's hand-crocheted afghan off the couch and a monstrous, humorous creature was revealed. She wore one of my mother's housedresses. Her body was made of pillows. She had coffee cups for breasts and cardboard mailing tubes for legs. She wore my mother's bowling shoes and carried her patent-leather dress-up bag on her white elbow-length-gloved hands. Her arms were golf clubs and her neck was a mop handle. Her head was the mop itself; Lincoln had combed it back and held it in place with my barrettes and rubber bands. Aunt Matilda's eyes were covered by my mother's rhinestone sunglasses. Lincoln had made her nose from an old bronzed baby shoe, and Aunt Matilda's mouth was a red pepper. She lay on the couch looking half dead."Say hello," Lincoln ordered me, "and curtsy.""Hello, Aunt Matilda," I said. I curtsied. Lincoln's voice changed to a falsetto."Hello, you darling little sweet thing you," said Aunt Matilda. "I can't believe how you've grown grown grown. What a lovely woman you've become. Are you married yet?""I'm only five," I explained."Well, I would have taken you for eight on any day," said Aunt Matilda.This pleased me immensely."I traveled all the way from Oregon just to see you," said Aunt Matilda. "Now tell me all about school."I was growing impatient. My feet were freezing and I had to go to the bathroom badly."I'm in kindergarten," I said.Lincoln's voice broke in. "Stand still," he commanded me, "or you'll give your aunt heart failure."I tried to obey."What do children do in kindergarten?" cooed Aunt Matilda. "I'm so very old I can't remember."I shrugged. "We learned to tie our shoes.""That's lovely, dear," said Aunt Matilda. "Why don't you show me how to tie a bow and I'll give you one of the fabulous presents I brought all the way from Oregon."I looked at Aunt Matilda's hideous face, and tears welled in my eyes. I was the second slowest in my class and I didn't want to admit it to her. I couldn't get both ends of the bow even, and often I was kept after school until I did. Aunt Matilda looked scornful."You'll give her a stroke," Lincoln hissed. "And then she'll lose the use of the whole right side of her body. Anyway, she has presents for you."I couldn't control my bladder. Pee streamed down my legs onto the rug."What are you doing?" Lincoln cried. I started to bawl. He dashed into the bathroom and brought out a roll of paper towels and Johnson & Johnson talcum powder."Just stand still," he pleaded with me. Sloppily he rubbed me up and down with the paper towel and covered my underpants and legs with talcum powder."Go to your room," he whispered. "I'll explain to Aunt Matilda."I was terrified that Lincoln would punish me for ruining his game, but he seemed genuinely upset for me."She's a little young," I heard him tell his large puppet. "But she'll be a killer when she grows up.""She ought to marry you, Lincoln dear," I heard Aunt Matilda say. I knew she was right. Deep in my heart there was no one I wanted to marry besides my brother.A few minutes later I heard Marie, our German maid, trudge down the steps from her attic room. She must have cleaned up the whole mess and Aunt Matilda, too. Later on, she came into my room and washed me and changed my clothes. She never said a word except to tell Lincoln I was okay.

My brother formed incredibly close relationships with both our German maids--the one we had until I was six and the one who took her place and stayed until I was a teenager. He claimed to have taught them both English, American history, and how to mambo. He told me he had genuine political sympathy for them since he was certain my mother had brought them here just to get revenge on the Nazis. He was in love with both of them, and neither Marie nor Annie ever suffered the nasty verbal abuse he doled out to the rest of the household. He told them his problems. He listened to them when they scolded him. He played them jazz and blues records. He called their families in Germany on holidays, and when they were homesick he proposed to both of them. Later, when Lincoln drifted from psychiatric hospital to rehabilitation center, I fantasized that he'd recover much more quickly if he was attended by German maids rather than by a psychiatrist or social worker. I've never understood what it was about those two women that calmed my brother or what it was that gave them such endless tolerance for him. There's a key there somewhere. I keep looking for it, to find out how I could have loved him like a German maid.Lincoln lived in filth from a young age. He started smoking early and cigarette butts made crusty mountains in his ashtrays and trails along his floor and sheets. As early as eighth grade he began writing prolifically, and his papers were stuffed in sock drawers and shoved under dressers. The India ink from his drawings spilled into multicolored stains. He'd begun what would be a lifelong passion for collecting symbolic objects. Broken toys, half-cracked clocks, strings, and keys were hidden in corners of his closet, the floor of which overflowed with dirty clothes. I know all this because I snuck into his room whenever he was out. I thought he was a genius and I wanted to read every word. I believed it might be catching; that I'd gain wisdom, maturity, or religious enlightenment by glancing at an unfinished cartoon or mouthing the words of one of his poems. Years later, when I sneaked through the smashed windows of his Lower East Side storefront to recover any papers or objects that might be too private to fall into the hands of the press or scavengers, I was struck with horror at how Lincoln's world looked like the stinking hovel of a degenerate madman. The objects seemed random, rusty. Cat food and litter covered everything. The papers were yellowed scraps. They had become incoherent notes scribbled on torn paper. I felt as if a bomb had dropped and I was walking among the remains. I thought about how schizophrenia was a degenerative disease and how he had fought the chaotic choruses, movies, and sound tracks in his brain to hold on to the moments of clarity that were allotted him. From an early age, he'd spend whole days in bed, exhausted from his battles. He was often pasty-faced, thin, with bloody gums and lingering colds. He had many small infections, from hangnails to conjunctivitis. His eyesight grew worse and worse. His game rules and hallucinations must have taken a serious toll on his body. I've been told by several doctors and psychologists that the life expectancy of a severely schizophrenic person is shorter than that of a so-called normal man. I never listened. And I never expected my brother to die young. No one told me he was diagnosed as schizophrenic until I was in my twenties.Every time my brother made a mess, one of his German maids cleaned it up. Still, his filthy room was an issue around our house. So was the fact that he refused to wash his neck or clean his ears. His stench sometimes brought my mother to tears. My mother's tears caused my father to explode in fury. Then Lincoln refused to talk to me. Or he'd visit me in the middle of the night, waking me out of a deep sleep, and demand to know why I'd turned our parents against him. Especially when he loved me so much. No matter how much I swore my allegiance, he didn't believe me. He pinched me under the sheets and crawled over me with his hands around my neck. These night visits developed into a repeated ritual. It was a strange dimension to our relationship--one I didn't remember until I was old enough and strong enough to bear the consequences."You were born a brat," he'd whisper, "and that's what you are. You have brattiness in your veins where other little girls have sweet things like cotton candy. You're just lucky I believe in Gandhi, because there really shouldn't be any brats allowed in this house. There should be brat houses like orphanages. And that's where you should go."I wouldn't dare to whimper. After he left, I lay frozen, wide-awake, listening to Lincoln listening to Frank Sinatra until the dawn brought safety with the sound of the maid preparing breakfast.The principal of Lincoln's private school called in my parents and told them that he, the dean, and the school psychologist were recommending that Lincoln attend a special institutional school where he would receive strong discipline and therapy. I don't know the reasoning for this recommendation. A dismal anxious mood settled in the household. Lincoln kept entirely to his room. My mother went to bed. Meals were delivered by the maid as if we had room service. My father's voice boomed down our hallways as he talked to specialist...

From Kirkus Reviews

Swados (Listening Out Loud, 1988, etc.), a writer/composer best known for the musical Runaways, offers a painful memoir of growing-up in a family beset by mental illness--with compelling ghastliness in many of the details but insufficient overall drama or insight. A brief prologue introduces the family: the Swadoses--Jewish, upper middle class--in 1950's and 1960's Buffalo, where ``appearance was everything.'' Then come four long chapters, each focusing on one member of the family. First, and always foremost, is Elizabeth's schizophrenic older brother, Lincoln: eccentric, filthy, and brilliant as a child, he fell wildly ill during college, attempted suicide at 24 (losing an arm and a leg), and became a Lower East Side ``character'' who eventually died in wretched isolation. Next Swados turns to her depressed, alcoholic mother--sporadically creative but ``in her heart...a lonely orphan'' who committed suicide when the pressures (her son's condition, her suffocating marriage) became too much. Then there is father Robert, who reacted to the family illnesses (including his mother's schizophrenia) with rage and sheer activity, losing himself in an all-consuming sports-law career. And finally there's Elizabeth herself, always driven to be ``the child about whom my father could tell stories to his clients'': She overachieved like crazy, composing and performing, getting admitted to Bennington at 16, scoring Medea at La Mama for Andrei Serban at 19; she also exhausted herself with wild living, determined not to be like her conformist parents. The four-part structure here makes for a repetitious and often anticlimactic narrative, without satisfying shape or development. Swados's prose doesn't have enough variety or grace to fill out such an ambitious design. But her sincere attempt to understand her family's misery is often affecting, and the story of brother ``Lincoln Sail'' (as he called himself) is, though disjointed, grimly fascinating. -- Copyright ©1991, Kirkus Associates, LP. All rights reserved.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherFarrar, Straus and Giroux

- Publication date1991

- ISBN 10 0374152195

- ISBN 13 9780374152192

- BindingHardcover

- LanguageEnglish

- Edition number1

- Number of pages288

- Rating

Shipping:

US$ 3.99

Within U.S.A.

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Four of Us: The Story of a Family

Seller: More Than Words, Waltham, MA, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. . . All orders guaranteed and ship within 24 hours. Your purchase supports More Than Words, a nonprofi t job training program for youth, empowering youth to take charge of their lives by taking charge of a business. Seller Inventory # BOS-V-08g-01142

Quantity: 1 available

The Four of Us: The Story of a Family

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00077643109

Quantity: 1 available

The Four of Us : The Story of a Family

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 6265153-6

Quantity: 1 available

The Four of Us : The Story of a Family

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 7709705-6

Quantity: 2 available

The Four of Us: The Story of a Family

Seller: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.14. Seller Inventory # G0374152195I4N00

Quantity: 1 available

The Four of Us: The Story of a Family

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.14. Seller Inventory # G0374152195I4N00

Quantity: 1 available

The Four of Us: The Story of a Family

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.14. Seller Inventory # G0374152195I3N10

Quantity: 1 available

The Four of Us: The Story of a Family

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.14. Seller Inventory # G0374152195I3N00

Quantity: 1 available

The Four of Us: The Story of a Family

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.14. Seller Inventory # G0374152195I4N00

Quantity: 1 available

The Four of Us: The Story of a Family

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.14. Seller Inventory # G0374152195I4N10

Quantity: 1 available