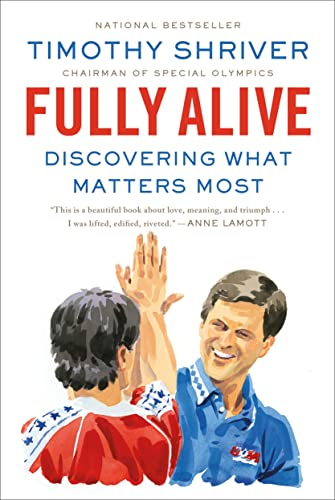

Items related to Fully Alive: Discovering What Matters Most

Synopsis

On a quest for what matters most, Timothy Shriver discovers the joy of being fully alive

As chairman of Special Olympics, Timothy Shriver has dedicated his life to the world's most forgotten minority-people with intellectual disabilities. And in a time when we are all more rudderless than ever, when we've lost our sense of what's ultimately important, when we hunger for stability but get only uncertainty, he has looked to them for guidance. Fully Alive chronicles Shriver's discovery of a radically different, and inspiring, way of life. We see straight into the lives of those who seem powerless but who have turned that into a power of their own, and through them learn that we are all totally vulnerable and totally valuable at the same time.

In addition, Shriver offers a new look at his family: his parents, Sargent and Eunice Shriver, and his uncles, John, Robert, and Edward Kennedy, all of whom were resolute advocates for those on the margins. Here, for the first time, Shriver explores the tremendous impact his aunt Rosemary, born with intellectual disabilities, had on his entire family and their legacy.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Timothy Shriver is a social leader, educator, activist, film producer, and business entrepreneur. He is the third child of Eunice Shriver, founder of the Special Olympics. As chairman of the Special Olympics, he serves more than three million athletes in 180 countries. He cofounded and currently chairs the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL), the leading research organization in the United States in the field of social and emotional learning. Shriver earned his undergraduate degree from Yale University, a master's degree from Catholic University, and a doctorate in education from the University of Connecticut. He lives in Maryland with his wife and five children.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

ONE

Boat Races

When I was about five years old, I fell in love with my first game: “boat races.” My mother and I played it on the little streams that ran through the woods at the edge of the vast field that stretched out behind our house. Those woods were a whole world to me. Looking out from my back door, all I could see was the field, and then the magical woods. On dark nights, beyond the vast expanse of the empty black field and the uneven, inky line of the woods rising above it, I could also see a row of four radio towers blinking red and white like silent sirens.

As a little boy, many nights I’d lie in bed and look out the window and watch those radio towers blinking their secret signals of warning. I knew they were located in the faraway city, but all I knew of the city was that my mother and father went to work there. Sometimes they came home with lots of friends, and sometimes they came home with beaten looks on their faces. Little children remember only moments of heaven or hell. One time when I was four, my mother came home to tell me my uncle had been murdered and I should run along and find something to do. But on other days, she would take me off alone, just the two of us, down through the field and into the woods to play our special game of boat races.

It was not an easy game. The “boats” were actually small sticks, and the race was actually a competition between my stick and my mother’s to see which could go down the stream fastest. So the first challenge was to find a good stick—one that floated well and didn’t have any protrusions that would get stuck on a leaf or a rock. A good boat was small enough to be quick but hefty enough to catch the current.

Once we’d picked our boats, the second challenge was to throw them into the stream at the count of three, hitting the water in just the right place so they would catch the current and go. Then came the breathless part: watching my boat wiggle and wash its way down the stream toward an imaginary finish line, cheering like crazy, encouraging it on its journey toward (I hoped) victory. And then heaven’s most often repeated exclamation: “Let’s play again!”

I loved the ritual of the game—the long walk down the field holding my mother’s hand, the passage from the open grass of the cow pasture into the shade of the huge Maryland oaks, the crunchy path across the leaves and twigs of the forest floor to the edge of the stream, and the furious search for high-quality boats that I could race against my resolute opponent, Mummy. We were all alone in those woods, Mummy and me: quiet, beyond the reach of the hated phone, beyond the city, the cars, and all those people asking Mrs. Shriver what she wanted, when she wanted it, and where she wanted it. All I had to do was pick up a stick and I had the power to make a boat come to life. I could bring the only eyes and ears and heart and mind in the world that I cared about—those of my mother—to focus on my little boat as it navigated mighty rapids, skittered around treacherous leaves and pebbles and occasional whirlpools, and glided toward a win.

They say a child can believe in anything—like Santa Claus with his elves; like leprechauns with their rainbows and pots of gold; like boats made out of sticks and their daring races against the hazards of the elements; like a child being the center of his mother’s life. In those days of boat races, I believed. I believed in things I couldn’t see and in the secret power I had to change the world into a place of love and mystery and eternity. It wasn’t that I didn’t know about the monsters with grotesque faces and devastating strength that could attack. I did, and from an early age. It’s just that the magic of the game was powerful enough to defeat them.

Those are the kinds of things I believed as a child. It took a long time for me to find my way back to them, but I believe in them still.

TWO

Much Is Expected

My understanding of belief goes back to my grandmother Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy. She was a woman of warm elegance, impeccably punctual at family meals, fond of long walks (which we grandchildren were often invited to join), and full of witty stories. She went to mass every day and frequently alluded in conversation to her faith and to the teachings of the Catholic Church. She would sometimes speak of the role faith played in the public events of her life—visits with the Pope in Rome, gifts to the Archdiocese of Boston in support of Catholic causes, the political careers of her sons.

But she also had private lessons for her grandchildren. She was especially fond of paraphrasing Luke 12:48, the parable of the faithful servant: “Of those to whom much is given, much is expected.” “Expected” was a word that had clear implications for her and for everyone in my family. Expectations were serious business, because, as I could easily discern from the large houses and plentiful possessions and ambitious people all around me, we had been given a lot. It was my job to figure out how to fulfill the expectation that I would give back.

Figuring it out, for me, took place in the midst of some rather extraordinary events. My family was immersed in politics—not just any politics, but the politics of the Democratic Party in the second half of the twentieth century. My grandfather became involved in the campaign of Franklin Roosevelt, but his role in that campaign, and his subsequent chairmanship of the fledgling Securities and Exchange Commission, was driven not so much by idealism as by pragmatic ambition. Joseph P. Kennedy was a conservative man in an administration many feared to be too leftist, hired because he spoke the language of Wall Street and could make SEC regulation palatable there. The business world had found Roosevelt’s thundering inaugural words ominous:

The money changers have fled from their high seats in the temple of our civilization. We may now restore that temple to the ancient truths. The measure of the restoration lies in the extent to which we apply social values more noble than mere monetary profit.

My grandfather’s work, often as not, involved sending a more moderate and diplomatic version of this same message: “Don’t worry, he didn’t mean itthat way.” The SEC was about restoring public confidence in the free market, not about shutting it down.

My parents, however, learned the more idealistic version of New Deal politics. They not only supported FDR, but alsobelieved in his message of courage and justice in the face of weakness and greed, and they raised my brothers and sister and me on it. Their Roosevelt was a man who’d proved that government could be a force for fairness in the economy. He was committed to the ideals of artists pursuing their creative passions, to public works, to the great economist John Maynard Keynes. He sided with the poor and against the rich; he envisioned a country where the elderly could be free of the destitution and stigma of old age. He believed, most of all, in action. His protruding jaw and his energy were as powerful as his legislation. I grew up with role models who were eager to forge ahead in the mold of Roosevelt: never fearing anything, least of all fear itself.

Most of the significant adult men in my life served in the armed forces during World War II. My father, Sargent Shriver, saw heavy combat in the Pacific theater and several times escaped with his life only by chance. One of my uncles, Joe Kennedy, Jr., was killed in a high-risk secret mission in the European theater. President Kennedy’s much-heralded heroism in naval warfare was part of my childhood’s daily conversational fare, and I wore PT-109 tie clips to every family event. Most of our friends and acquaintances had war stories, which they told more often than they probably realized. A longtime family employee who became a second father to me, Richard Ragsdale, often drove us children to important events, and while he drove he would recount the stories of the shrapnel wounds he’d suffered in the 1st Armored Division under Patton in North Africa. He liked to end his hellish tales by showing us a photo he’d taken upon his arrival in Milan as an intelligence officer: it was a black-and-white of Mussolini hanging upside down from a stanchion, executed in advance of the arrival of American troops.

With the New Deal and World War II as backdrops, my parents were married and started their family in Chicago, where my father had gone to work in the sprawling Merchandise Mart owned by my grandfather—perhaps the most lucrative investment of his storied business career. The wealth my grandfather had created was also a focus of the lessons we learned as children. Among the many gifts my parents gave to me and my siblings was their determination that the comfort and privilege of our childhood would not make us feel self-satisfied or entitled. My father reminded us relentlessly that the children of the rich “usually amount to a hill of crap,” warning that such a fate was not an option for us. Both of my parents were vigilant in rooting out any traces of arrogance. One didn’t have to go far in treating others with disdain or snobbery to hear a sharp, scowling adult crackdown: “Just who do you think you are, talking that way?” By a strange and muddled calculus, we learned of our privilege mostly in the context of denying it and, even more important, of repaying it.

There was also family grief—often the result of sudden, shockingly painful, enormously public events. In some ways, I was spared the full brunt of these unspeakable tragedies, since my own parents and siblings survived into my adult life. But in other ways, the large, extended, boisterous, and idealistic family system of which I was a small part was repeatedly crushed by violent losses. Through those losses, I learned one of the most problematic lessons of my childhood: grief and other emotional traumas are not to be dwelt upon and in fact are barely to be acknowledged. We had one unspoken rule as children: deal with loss on your own, in whatever way you can. At the slightest sign of sadness, a stern reminder came down from above: “Get on to yourself! Everyone’s happy in heaven, and besides, you could be much worse off than you are.” Between the benefits of our wealth and the consolations of our faith, we had been given much, and in return we were expected not to show or feel or dwell in self-pity or pain. In the unlikely event that we questioned God’s wisdom or wondered aloud why it mattered that children in Biafra were worse off than we were, it would only get worse. “That’s enough!” End of story.

In the vacuum left by this emotional hush policy, religion became an outlet. Both of my parents were devout Roman Catholics, attending daily mass, reading extensively in religious ideas, and actively participating in the daily life of religious orders and institutions. For them, faith yielded enthusiasm and even fun, as they would lead debates about religion, poke fun at the eccentricities of this priest or that nun, and try to inculcate in us a sense of the relevance of religious doctrines. At the same time, in a kind of mystical sleight of hand, emotional issues were always converted to religious ones. We prayed the Rosary as a family on many occasions, and I remember hearing my mother dedicate the prayers again and again to the repose of her brothers’ souls, intimating that our grief could be channeled through the beads and converted from pain to peace. Sometimes when we rode in the car with my father, he would take the opportunity to remind his captive audience that the Sermon on the Mount was “the greatest speech ever given—the greatest account of how to be happy ever given.” Like my mother, he seemed convinced that emotional happiness could somehow emerge from devotion to Christian traditions and liturgical practices. When I once asked him about the insights of psychology, he was quick to remark that Freud and others might be helpful to some, but we had our faith, and it was far better than any therapist.

Therapists or no therapists, religion drew me in. Prayer was a practice where emotion was allowed and even nurtured. Church was the place where peace was sought as a personal experience in quiet and not just discussed as a political ideal. The Bible was a book about lost souls and escapes to freedom and suffering that was faced and heaven that was achieved. I watched my parents in church and saw my dad pull at his forehead in prayer and my mother look to statues of Mary and try to emulate her example of faith. I was an altar boy by the time I was seven, but I was also more than that: I was on a faith journey and already wondering, “Who is God and how can I find God’s answer to my search for what matters most?”

But time in church, no matter how frequent, was still the exception. In the day-to-day, my family exuded restlessness. We were restless to fight poverty, restless to get elected, restless to win at sports, restless to help people with intellectual disabilities, restless to be charming, restless in a million ways. In part, this restless social energy found its healthiest outlet in competition, and competition in everything was the norm. My father would wake early in the morning and challenge everyone to see who was going to be the first one downstairs to breakfast, and the race was on. We would compare our performance on school report cards to see who was smartest, play touch football to see who was fastest, ride horses to see who was best, recount stories of parties to see who was the most charismatic, read the newspaper to see who had the highest poll ratings, work elections to see who could win political power, play water polo on weekends to see who could endure the most physical punishment. We were constantly on the lookout for chances to win and, equally important, for chances to guard against losing. Through it all, we would laugh at our failings and laugh at the world, just as we yearned to overcome both. The only lesson that rang as clear as those of high expectations, social justice, and religious fidelity in our family was the law of competition. Our self-definition and our individual value were measured on a scorecard. We were satisfied only if we were winning at something.

Ironically, this family system—so immersed in the world of politics, so restless in pursuit of power, so intensely focused on action—also kept returning us to the interests of life’s most vulnerable. Just as we raced around our backyard and campaigned around the country and journeyed around the world, we were always doing so with an eye on the need to serve those who had neither wealth nor power nor influence. Somehow, this never seemed inconsistent to me and never created any conscious tension in my mind during my youth, but looking back, it was a bit of a roller coaster. We would travel abroad and meet a prime minister or a king and then, on the same day, visit an institution for people with intellectual disabilities or a Peace Corps project focused on sewage. My parents would hold parties for cabinet secretaries and movie stars, and the next day load up our station wagon to deliver canned goods and turkeys to a soup kitchen. At the dinner table, my mother would ask us to explain our position on the rising poll numbers of an incumbent United States senator and then explain what we had learned about how starvation could possibly persist in a world with so much wealth. It was all of a piece—politics, power, wealth, faith, competition, and the outrage of injustice. It was bound together by my grandmother’s rule: you have been given much; you must serve others in exchange. “Serve, serve, serve,” my father once said in a rousing speech. “It is the servants who will save us all.”

In my immediate family, service was not primarily about electoral politics, and that was fine with me. Politics, after all, had produced the trauma of family deaths in the sixties, a frustrating string of public losses in the 1972, 1976, and 1980 presidential elections, and the humiliating lifelong experience of being a surrogate. Politics, despite its glittering reputation as an avenue for fame, camaraderie, and big ideas, seemed mostly an occasion for being asked, “Which one are you?” Campaigns could be exciting and the great ideas were compelling, but for me it was mostly a world of intense pressure, superficial rhetoric, mean-spirited confrontations, exhausting family separations, and experiences of personal insignificance. We laughed on campaigns, we went door to door with spirit, and we stood happily when our parents and uncles would recognize us in speeches, but elective politics was certainly not set up to make a child feel special. Quite the contrary: it made us feel small—in stature as children and in significance as young adults. For the most part, it sucked.

Another side of politics, however, did have an allure. It was politics with a small “p”—engagement in political and social organizations that existed to advance a public good. This was really the work of my side of the family. My father came late to electoral politics. Despite being the Democratic candidate for vice president of the United States in 1972 and subsequently running in presidential primaries, he was much more gifted—and happier—at the work of creating and championing social programs. Similarly, although my mother was often referred to as a political animal, she was never herself a candidate for public office. Rather, she chose to pursue her political ideals through advocacy and social programs. And the programs both my parents created were extraordinary.

These programs were also a part of my life, even though I was just a child. When I was six years old, my father returned from one of his many trips around the world with a special gift for the kids. We each unwrapped beautiful navy-blue sweat suits, the jackets embroidered on the right with our names and on the left with the logo of the United States Peace Corps. Our “Peace Corps suits” would be worn on Saturday after Saturday, when my father would convene his senior staff at our house in suburban Maryland for all-day working sessions. The Peace Corps was already the apple of the nation’s political eye, embodying the American values of exuberance, idealism, and tirelessness. And I could be a part of it every time I put on my suit and showed it off to the grown-ups who were working in my living room. There, politics was not about power or the defeat of opponents but rather about important values and intimacy with my dad. I remember once, when I was about eight years old, hearing him call out to an assembled team of colleagues in the backyard: “Look at Timothy run in his Peace Corps suit! Look how fast he is!” The fight for social justice took place on a big stage, but it was also about family.

There were many more programmatic efforts like this in my house—Head Start was conceived in that same living room, and in one way or another so were the Legal Services Corporation, Upward Bound, Job Corps, Community Action, and Foster Grandparents. I couldn’t have known, as a child, about all the injustice and challenges that confronted these efforts to fight poverty, or about the real anger and division they were trying to address in the tense and volatile cities of the 1960s. What I did know was that these efforts were both important and fun—a rare combination that yielded a deep sense of satisfaction. And no work better captured that combination than the revolutionary experiment my mother conducted at that same house, Timberlawn, during the summers of my early childhood: Camp Shriver.

My mother is one of nine children, three of whom—Jack, Bobby, and Teddy—were known for their extraordinary political careers. My mother’s sisters, while less recognizable to most, were also people of enormous energy and achievement. My aunt Jean founded an international arts program for people with disabilities and served as an ambassador. My aunt Patricia was an animated beauty who spent virtually her entire life volunteering for the causes that drove her siblings, and she lived at the center of New York’s cultural life. But my aunt Rosemary, who died in 2005, was perhaps the most extraordinary of my mother’s siblings.

Rosemary was born in 1918. I remember my mother often explaining Rosemary’s challenges as resulting from a troubled delivery. “Rosemary lost oxygen during her birth, and we think that’s what caused her difficulties. Loss of oxygen to the brain can do that—can cause problems for life.” I never heard this explanation of Rosemary’s condition corroborated, but whatever the cause, it became apparent soon after her birth that, in the jargon of the day, Rosemary was “mentally retarded.”

As she reached school age, her disability made her unable to keep pace with her siblings. Her parents, like millions of other parents around the world whose children are different, struggled to find any support or help. Rosemary attended the same schools as her siblings until she was eleven. By then she had fallen so far behind that her parents sent her away to an experimental boarding school in Pennsylvania, which was designed for the education of the “feebleminded.” Over the next twelve years, she would attend multiple schools, with brief intervals of living at home. None of her teachers seemed to know quite what to do with her; there was constant pressure on the family to do something to fix her.

My grandparents must have experienced the painful tension between wanting to fight for their child and wishing she would go away to be cared for elsewhere, out of sight, the weaknesses and embarrassing flaws hidden from view. At times, Rosemary must have felt desperately alone. At other times, she must have felt the warmth of the family who sheltered her, although her siblings undoubtedly struggled with how to make sense of the world from the point of view of their sister. They grew up loving someone whom others referred to as having something “wrong.”

Finally, at the age of twenty-three, Rosemary Kennedy underwent experimental brain surgery—a lobotomy—in an effort to correct the emotional and cognitive vulnerabilities that appeared to be growing worse. It was a disaster. The procedure left her with only the most limited verbal and motor abilities. She would spend the remaining six decades of her life in the custody of nuns and caregivers in a Wisconsin institution. By most accounts, my grandfather never saw her again—ending what had been a lifetime of affection. For more than two decades, her mother and siblings visited her rarely. In most ways, she was simply gone.

By the time I arrived, however—almost twenty years after the lobotomy—Aunt Rosemary had become a frequent visitor to our home. She would stay for a few days or a week and spend her days shuffling cards, swimming, taking walks, or visiting sites in Washington. Only when I was older could I see the vexing predicament into which she thrust us. We were a family who lived as though winning and gaining influence were indispensable to our happiness. How then could we explain why Rosemary’s life was of value, too?

In her own way, she may have had the most influence of any member of my family, because her message was by far the most radical: she was the only person I ever met who didn’t need todo anything to prove that she mattered. In the midst of an enormously competitive family system, Rosemary Kennedy lived a full life to the age of eighty-six without ever giving a speech, writing a book, holding a job, or garnering the praise of the mighty. Despite failing to meet any of the expectations that were imposed on the rest of us, she belonged. She didn’t have to do anything to earn that. Only in retrospect did I realize how, at some level, I envied her deeply. Her presence changed everything.

In any event, she was surely the catalyst for what took place in my backyard starting in the summer of 1962. There, my mother started a revolution and named it Camp Shriver. She was determined to prove to others a lesson Rosemary had proved to her years before, a lesson that remains shocking in its simplicity and shocking in its continuing and persistent disregard: people with intellectual disabilities are human beings, deserving of love, opportunity, and acceptance just as they are.

In the years before Camp Shriver, my mother had spent much of her professional energy touring facilities for people with intellectual disabilities, meeting with scholars and researchers, giving small grants to therapists and support agencies, and listening to parents and family members. That experience had led her to the point of fury and frustration, because the suffering of the people she met was so extreme, and so little was being done. Some combination of pain, outrage, and enthusiasm galvanized her to act. In 1962, she decided that the oppressed and forgotten children with intellectual disabilities who were grinding out their summers in the fetid institutions of Washington, DC, and suburban Maryland ought to be able to play games and have fun. And she further decided that since no one else seemed to care much, she would make it happen herself, in her backyard, with her children in tow. That’s where I came in.

What I remember of Camp Shriver spans a child’s emotional range: I went to the arts and crafts center at the camp, where along with other campers I built and painted my own wooden table and gave it to my father. I did the ropes course with other campers and walked the balance beams, hung from trees, and jumped through obstacles. I went with the other campers down to the riding ring and rode small ponies. And I wandered on summer afternoons through an array of games and activities that made my backyard into a virtual amusement park. My mother watched all this and noted shrewdly:

Should anyone be afraid of Wendell, a nine-year-old boy with the mental ability of a boy of four? He and Timothy, my own three-year-old son, did many things at our day camp at the same speed and proficiency and loved each other. Both picked up their clothes—with some prodding—after swimming; both caught and threw a ball with the same ability, although Wendell kicked much better than Timothy. Both had the same table manners. Sometimes they would throw the food and would then have to go without dessert. Both ran about the same speed and rushed back and forth. Wendell and Timmy would hold hands and run down the hill together. Wendell would help Timmy climb up the hill when he was tired.

Camp Shriver was a bonanza of fun, complete with games, balls, swimming, and a friend named Wendell.

But it was also curious, in ways I can now see quite clearly. It must have occurred to me that it was anything but ordinary to have a hundred or so people with intellectual disabilities in one’s backyard. Volunteers seemed to arrive at all hours of the day and evening, asking what to do. A vigorous, authoritarian former Olympic athlete, Sandy Eiler, was brought on to help manage the activities, but he, like others, had only the most limited sense of a plan. Prisoners on work release showed up regularly, tasked with some of the heavy labor involved in constructing games and moving equipment. Only occasionally did a camper’s emotional outburst or unrestrained behavior concern me. At the center of it all was my mother—excited, charismatic, demanding, completely immersed, and always on edge. At the time, Camp Shriver certainly didn’t seem to fall into the category of “revolutionary,” but though few noticed it, the revolution was on. For my mother, it was activism wrapped up with sports, faith, and social justice—her way of attacking the pain and rejection that had marred Rosemary’s life and hers. She was a camp director on a mission, and somewhere within her was Rosemary—a sister calling out for a chance.

During Camp Shriver, my child’s eye took in scenes that have stayed with me for decades. I remember some summer mornings being alone in my bedroom, peering out the window as the campers would arrive and assemble for the raising of the American flag, listening for the trumpeter who would play the national anthem, and for the singing of “If You’re Happy and You Know It.” I watched as volunteers helped guide campers from the school buses to the flagpole, where they lined up in disorderly rows as the flag ascended the pole and the trumpet played its lonely ode to the nation. Then the clapping and singing began. “If you’re happy and you know it, CLAP YOUR HANDS!”

I think I wondered many things as I watched the scene from my second-floor room. I was maybe four or five years old when I can first remember staring out my window as though it happened often; as though it happened yesterday. How do you become “happy” and how do you know it? What are “expectations” and whose should I meet? What matters most—becoming a senator or a president or playing outside with a child with intellectual disabilities in the pool? And who were these children with intellectual disabilities and why was it so important to help them be happy?

I think on some level I realized, even then, that my life was going to be about that scene. I was silent as I watched, my eyes fixed and wide, racing but motionless; my little mind searching the scene in front of me, pleading with it for clues for where I belonged.

All children have their share of moments in which time seems to stop and the full emotional and spiritual complexity of the world comes rushing through their eyes into their bones, there to stay for a lifetime. Flannery O’Connor once wrote that “anyone who has survived his childhood has enough information about life to last him the rest of his days,” and in the daily experience of Camp Shriver, I could see the questions of my life. I wanted to recapture my mother’s attention and escape to the woods and the wonderful delight of imaginary boats and speedy races and happy games. I wanted to figure out how to face the chaos and grief of our restless home while enjoying the excitement and lure of action and purpose that was right in front of my eyes. I wanted to explore the peculiar riddle of how we so often reject the very people and things that carry the secrets of belonging, and figure out what it would take to find my place. Later on, I wanted to learn how to pray, so that it would all make sense—how to kneel and grind out in silence my experience of the brokenness of the world, so that I could stand and defeat it in time and space.

Camp Shriver was a work of faith and fury made manifest in the most ordinary of tasks: we swam, we rode, we ran, we jumped. Some children came to our house, children whom most people thought of as worthless, and they got the chance to win at a few simple games. That was all. I played alongside them all those years, with only the faintest notion of the role they would later play in my life. Someday, I would realize how close those campers lived to the most important questions that I hungered to understand. And I would realize that they might just have shown me the most unlikely way to fulfill those great expectations my grandmother had instilled in me.

It would take me twenty years to come to understand that the biggest beneficiary of my attempt to make a difference for others would be me. And, even more remarkably, I would learn along the way that the most powerful role models in my search would not be the mighty and beautiful whom I had been raised to try to outdo, but instead the vulnerable and the forgotten on the edge of life whom I had been raised to help.

Copyright © 2014 by Timothy Shriver

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

FREE shipping within U.S.A.

Destination, rates & speedsSearch results for Fully Alive: Discovering What Matters Most

Fully Alive: Discovering What Matters Most

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Acceptable. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00057384679

Quantity: 2 available

Fully Alive: Discovering What Matters Most

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00055958061

Quantity: 4 available

Fully Alive: Discovering What Matters Most

Seller: Orion Tech, Kingwood, TX, U.S.A.

paperback. Condition: Good. Seller Inventory # 0374535825-3-33448573

Quantity: 1 available

Fully Alive: Discovering What Matters Most

Seller: BooksRun, Philadelphia, PA, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Good. Reprint. Ship within 24hrs. Satisfaction 100% guaranteed. APO/FPO addresses supported. Seller Inventory # 0374535825-11-1

Quantity: 1 available

Fully Alive: Discovering What Matters Most

Seller: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Good condition. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Bundled media such as CDs, DVDs, floppy disks or access codes may not be included. Seller Inventory # J01E-00571

Quantity: 1 available

Fully Alive: Discovering What Matters Most

Seller: Once Upon A Time Books, Siloam Springs, AR, U.S.A.

paperback. Condition: Good. This is a used book in good condition and may show some signs of use or wear . This is a used book in good condition and may show some signs of use or wear . Seller Inventory # mon0001410013

Quantity: 1 available

Fully Alive: Discovering What Matters Most

Seller: The Maryland Book Bank, Baltimore, MD, U.S.A.

paperback. Condition: Very Good. Reprint. Used - Very Good. Seller Inventory # 13-I-2-0206

Quantity: 1 available

Fully Alive: Discovering What Matters Most

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.67. Seller Inventory # G0374535825I4N00

Quantity: 1 available

Fully Alive: Discovering What Matters Most

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.67. Seller Inventory # G0374535825I4N00

Quantity: 1 available

Fully Alive: Discovering What Matters Most

Seller: HPB-Emerald, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

paperback. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Seller Inventory # S_385434760

Quantity: 1 available