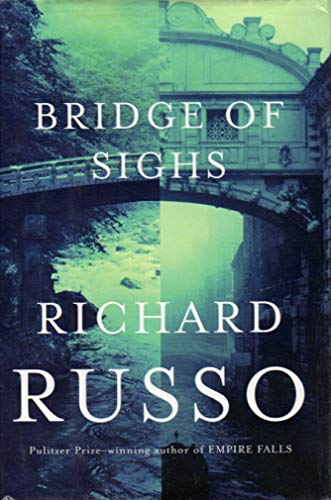

Items related to Bridge of Sighs

Synopsis

Six years after the best-selling, Pulitzer Prize–winning Empire Falls, Richard Russo returns with a novel that expands even further his widely heralded achievement.

Louis Charles (“Lucy”) Lynch has spent all his sixty years in upstate Thomaston, New York, married to the same woman, Sarah, for forty of them, their son now a grown man. Like his late, beloved father, Lucy is an optimist, though he’s had plenty of reasons not to be—chief among them his mother, still indomitably alive. Yet it was her shrewdness, combined with that Lynch optimism, that had propelled them years ago to the right side of the tracks and created an “empire” of convenience stores about to be passed on to the next generation.

Lucy and Sarah are also preparing for a once-in-a-lifetime trip to Italy, where his oldest friend, a renowned painter, has exiled himself far from anything they’d known in childhood. In fact, the exact nature of their friendship is one of the many mysteries Lucy hopes to untangle in the “history” he’s writing of his hometown and family. And with his story interspersed with that of Noonan, the native son who’d fled so long ago, the destinies building up around both of them (and Sarah, too) are relentless, constantly surprising, and utterly revealing.

Bridge of Sighs is classic Russo, coursing with small-town rhythms and the claims of family, yet it is brilliantly enlarged by an expatriate whose motivations and experiences—often contrary, sometimes not—prove every bit as mesmerizing as they resonate through these richly different lives. Here is a town, as well as a world, defined by magnificent and nearly devastating contradictions.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Richard Russo lives with his wife in coastal Maine. He is available for lectures and readings thorugh the Knopf Speaker's Bureau. http://www.knopfspeakersbureau.com.

Reviews

Reviewed by Ron Charles

Richard Russo was already the patron saint of small-town fiction, but with his new novel, Bridge of Sighs -- his first since the Pulitzer Prize-winning Empire Falls -- he's produced his most American story. Once again he places us in a finely drawn community that's unable to adjust to economic changes, and with insight and sensitivity he describes ordinary people struggling to get by. But more than ever before, Russo ties this novel to the oldest preoccupations of our national consciousness by focusing on the nature of optimism and the limits of self-invention. This, he writes, is "the narrative of our family, its small, significant journey. Is this not an American tale?" Indeed, no other modern author has defied the "small" in small town with such passion. On the first page of Bridge of Sighs, Russo dismisses any concern about provincialism: "Some people, upon learning how we've lived our lives, are unable to conceal their chagrin on our behalf, that our lives should be so limited, as if experience so geographically circumscribed could be neither rich nor satisfying."

Here is a story to knock those condescending city slickers on their backsides, a story true to the pace and tenor of town life but rife with all the cares and crises of people everywhere. It takes place over many decades in Thomaston, N.Y., where the tannery slowly laid off and poisoned residents until most of them died or moved away. But not all-around nice guy "Lucy" Lynch, who grew up here, never left and is now nearing retirement. He acquired that embarrassingly feminine nickname in kindergarten when the teacher called for "Lou C. Lynch." All this and much more is explained in a history he's writing of the town and his life, a project inspired by an upcoming trip to Italy, where he hopes to see an old friend. He tells his wife that it should take 50 pages, "a hundred, tops," but since we've got 500 to go, we know that's misleading. Lucy's other misdirections are harder to spot, although he admits early on that "it is tempting to lie [about] everything." Why such a blessed and well-liked man should feel tempted to lie about anything is one of the many mysteries that slowly unfold.

Bridge of Sighs crosses through many subjects and themes -- it's Russo's most intricate, multifaceted novel -- but the story revolves around Lucy's relationship with his father, the man he adored and resembles in so many ways that it troubles him. Big Lou was a slightly goofy, sentimental man who grew up during the Depression but emerged convinced "that we were living a story whose ending couldn't be anything but happy." There's a touch of Willie Loman here, except in this version, against all odds, he does okay. A milkman at the dawn of the supermarket era, Big Lou refuses to acknowledge the imminent demise of his career. Lucy's mother, on the other hand, is a sharp, realistic woman, who finds her husband's unbridled optimism exasperating. She makes a point of contradicting his cheery predictions, but it makes no difference to Big Lou, who "maintained, if you kept your nose clean, good things were eventually bound to happen to you." Lucy spends much of the novel negotiating these opposing points of view, aware that he always took his father's side against his mother's deflating realism. "I still remember how much this upset me," Lucy writes. "There wasn't supposed to be any limit to the benefits of hard work and honesty, and her saying there were limits implied that she didn't believe in America, or, worse, in us." Though decades have passed, Lucy remains torn between the two people who loved him, still trying to work out what kind of man he has become. This is not a particularly dramatic story -- a racially charged high-school beating provides the only real fireworks -- but Russo's sensitivity to the currents of friendship and family life, the conflicts, anxieties and irritations that mingle with affection and loyalty, make Bridge of Sighs a continual flow of little revelations.

The most interesting relationship in the novel is Lucy's unlikely friendship with Bobby Marconi, a tough kid who despises his abusive father as much as Lucy adores his own. He's confident and athletic, the mirror opposite of Lucy. Their friendship is badly one-sided, but Lucy is too infatuated to notice, and Bobby is just kind enough to resist telling this nerdy kid to get lost. Even after Bobby and some other ruffians stuff him in a trunk and traumatize him for the rest of his life, Lucy remains determined to believe that his friend wasn't involved.

Russo narrates significant sections of the novel in the third person, filling in details about Bobby's disturbing family life and "Lucy's terrible neediness." In addition, we get several chapters narrated by the adult Bobby, now 60, a famous artist living in Italy. The cumulative effect is a story of constantly evolving complexity and depth, a vast meditation on adolescence and the way it's remembered and misremembered to serve our needs.

It's peevish to complain about anything in such a lovely, deep-hearted novel, but I couldn't help letting out a few sighs of my own as the plot continued to branch out. There's simply too much here and too much redundancy. Lucy suggests that "it's all important," but as much as I enjoyed the book, I'm not convinced. Two of these characters are obsessed with writing very long stories, and Russo seems to have picked up the same compulsion. When he gets caught up in the thrills of a high-school romance -- Which boy will she choose? -- the Bridge of Sighs seems to be crossing over "Dawson's Creek." A late section involving Lucy's wife and an adorable little black child sounds extraneous and precious. And there's a tendency toward portentous profundity: "Odd, how our view of human destiny changes over the course of a lifetime. In youth we believe what the young believe, that life is all choice. We stand before a hundred doors, choose to enter one, where we're faced with a hundred more and then choose again. We choose not just what we'll do, but who we'll be," etc., etc. At such times, the plot, which is never particularly energetic, stalls, and the characters seem overwhelmed, rather than sustained, by the author's wisdom. Listed like this, these complaints sound more damning than I mean them to. Actually, in the course of this enormous and enormously moving novel, I was continually seduced by Russo's insight and gentle humor, his ability to discern the ways we love and frustrate each other. Toward the end, before a trip to Boston, Lucy writes, "We will leave this small, good world behind us with the comfort of knowing it'll be here when we return." One sets down Russo's work with the same comforting reassurance.

Copyright 2007, The Washington Post. All Rights Reserved.

SignatureReviewed by Jeffrey FrankRichard Russo's portraits of smalltown life may be read not only as fine novels but as invaluable guides to the economic decline of the American Northeast. Russo was reared in Gloversville, N.Y. (which got its name from the gloves no longer manufactured there), and a lot of mid–20th-century Gloversville can be found in his earlier fiction (Mohawk; The Risk Pool). It reappears in Bridge of Sighs, Russo's splendid chronicle of life in the hollowed-out town of Thomaston, N.Y., where a tannery's runoff is slowly spreading carcinogenic ruin.At the novel's center is Lou C. Lynch (his middle initial wins him the unfortunate, lasting nickname Lucy), but the narrative, which covers more than a half-century, also unfolds through the eyes of Lou's somewhat distant and tormented friend, Bobby Marconi, as well as Sarah Berg, a gifted artist who Lou marries and who loves Bobby, too. The lives of the Lynches, the Bergs and the Marconis intersect in various ways, few of them happy; each family has its share of woe. Lou's father, a genial milkman, is bound for obsolescence and leads his wife into a life of shopkeeping; Bobby's family is being damaged by an abusive father. Sarah moves between two parents: a schoolteacher father with grandiose literary dreams and a scandal in his past and a mother who lives in Long Island and leads a life that is far from exemplary. Russo weaves all of this together with great sureness, expertly planting clues—and explosives, too—knowing just when and how they will be discovered or detonate at the proper time. Incidents from youth—a savage beating, a misunderstood homosexual advance, a loveless seduction—have repercussions that last far into adulthood. Thomaston itself becomes a sort of extended family, whose unhappy members include the owners of the tannery who eventually face ruin.Bridge of Sighs is a melancholy book; the title refers to a painting that Bobby is making (he becomes a celebrated artist) and the Venetian landmark, but also to the sadness that pervades even the most contented lives. Lou, writing about himself and his dying, blue-collar town, thinks that the loss of a place isn't really so different from the loss of a person. Both disappear without permission, leaving the self diminished, in need of testimony and evidence. If there are false notes, they come with Russo's portrayal of African-Americans, who too often speak like stock characters: (Doan be given me that hairy eyeball like you doan believe, 'cause I know better, says one). But Russo has a deep and real understanding of stifled ambitions and the secrets people keep, sometimes forever. Bridge of Sighs, on every page, is largehearted, vividly populated and filled with life from America's recent, still vanishing past.Jeffrey Frank's books include The Columnist and Bad Publicity. His novel, Trudy Hopedale, was published in July by Simon & Schuster.

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

*Starred Review* Here is the novel Russo was born to write. Coursing with humor and humanity, the sixth novel by the bard of Main Street U.S.A. gives full expression to the themes that have always been at the heart of his work: the all-important bond between fathers and sons, the economic desperation of small-town businesses, and the lifelong feuds and friendships that are a hallmark of small-town life. Following a trio of best friends who grew up in upstate Thomaston, New York, over 50 years, the novel captures some of the essential mysteries of life, including the unanticipated moments of childhood that will forever define one's adulthood. Louis Charles ("Lucy") Lynch has spent his entire life in Thomaston, married for 40 years to his wife, Sarah, and finally living in the rich section of town, thanks to the success of his father's convenience stores. Long planning a trip to Venice, he tries in vain to communicate with the couple's best friend, Bobby Marconi, now a world-famous painter living in Venice. Meanwhile, the irascible ex-pat, now approaching 60 and suffering from night terrors, is still chasing women, engaging in fistfights, and struggling to complete his latest painting. Russo slowly and lovingly pieces together rich, multilayered portraits not only of the principals but also of their families, and, by extension, their quintessentially American town. It is a seamless interweaving of childhood memories (sometimes told from three points of view), tragic incidents (the town river, once the lifeblood of local industry, has become a toxic stew that is poisoning residents), and unforgettable dialogue that is so natural, funny, and touching that it may, perhaps, be the best of Russo's many gifts. Wilkinson, Joanne

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Berman Court

First, the facts.

My name is Louis Charles Lynch. I am sixty years old, and for nearly forty of those years I’ve been a devoted if not terribly exciting husband to the same lovely woman, as well as a doting father to Owen, our son, who is now himself a grown, married man. He and his wife are childless and likely, alas, to so remain. Earlier in my marriage it appeared as if we’d be blessed with a daughter, but a car accident when my wife was in her fourth month caused her to miscarry. That was a long time ago, but Sarah still thinks about the child and so do I.

Perhaps what’s most remarkable about my life is that I’ve lived all of it in the same small town in upstate New York, a thing unheard of in this day and age. My wife’s parents moved here when she was a little girl, so she has few memories before Thomaston, and her situation isn’t much different from my own. Some people, upon learning how we’ve lived our lives, are unable to conceal their chagrin on our behalf, that our lives should be so limited, as if experience so geographically circumscribed could be neither rich nor satisfying. When I assure them that it has been both, their smiles suggest we’ve been blessed with self-deception by way of compensation for all we’ve missed. I remind such people that until fairly recently the vast majority of humans have been circumscribed in precisely this manner and that lives can also be constrained by a great many other things: want, illness, ignorance, loneliness and lack of faith, to name just a few. But it’s probably true my wife would have traveled more if she’d married someone else, and my unwillingness to become the vagabond is just one of the ways I’ve been, as I said, an unexciting if loyal and unwavering companion. She’s heard all of my arguments, philosophical and other, for staying put; in her mind they all amount to little more than my natural inclination, inertia rationalized. She may be right. That said, I don’t think Sarah has been unhappy in our marriage. She loves me and our son and, I think, our life. She assured me of this not long ago when it appeared she might lose her own and, sick with worry, I asked if she’d regretted the good simple life we’ve made together.

Though our pace, never breakneck, has slowed recently, I like to think that the real reason we’ve not seen more of the world is that Thomaston itself has always been both luxuriant and demanding. In addition to the corner store we inherited from my parents, we now own and operate two other convenience stores. My son wryly refers to these as “the Lynch Empire,” and while the demands of running them are not overwhelming, they are relentless and time-consuming. Each is like a pet that refuses to be housebroken and resents being left alone. In addition to these demands on my time, I also serve on a great many committees, so many, in fact, that late in life I’ve acquired a nickname, Mr. Mayor—a tribute to my civic-mindedness that contains, I’m well aware, an element of gentle derision. Sarah believes that people take advantage of my good nature, my willingness to listen carefully to everyone, even after it’s become clear they have nothing to say. She worries that I often return home late in the evening and then not in the best of humors, a natural result of the fact that the civic pie we divide grows smaller each year, even as our community’s needs continue dutifully to grow. Every year the arguments over how we spend our diminished and diminishing assets become less civil, less respectful, and my wife believes it’s high time for younger men to shoulder their fair share of the responsibility, not to mention the attendant abuse. In principle I heartily agree, though in practice I no sooner resign from one committee than I’m persuaded to join another. And Sarah’s no one to talk, serving as she has, until her recent illness, on far too many boards and development committees.

Be all that as it may, the well-established rhythms of our adult lives will soon be interrupted most violently, for despite my inclination to stay put, we are soon to travel, my wife and I. I have but one month to prepare for this momentous change and mentally adjust to the loss of my precious routines—my rounds, I call them—that take me into every part of town on an almost daily basis. Too little time, I maintain, for a man so set in his ways, but I have agreed to all of it. I’ve had my passport photo taken, filled out my application at the post office and mailed all the necessary documents to the State Department, all under the watchful eye of my wife and son, who seem to believe that my lifelong aversion to travel might actually cause me to sabotage our plans. Owen in particular sustains this unkind view of his father, as if I’d deny his mother anything, after all she’s been through. “Watch him, Ma,” he advises, narrowing his eyes at me in what I hope is mock suspicion. “You know how he is.”

Italy. We will go to Italy. Rome, then Florence, and finally Venice.

No sooner did I agree than we were marooned in a sea of guidebooks that my wife now studies like a madwoman. “Aqua alta,” she said last night after she’d finally turned off the light, her voice near and intimate in the dark. She found my hand and gave it a squeeze under the covers. “In Venice there’s something called aqua alta. High water.”

“How high?” I said.

“The calles flood.”

“What’s a calle?”

“If you’d do some reading, you’d know that streets in Italy are called calles.”

“How many of us need to know that?” I asked her. “You’re going to be there, right? I’m not going alone, am I?”

“When the aqua alta is bad, all of St. Mark’s is underwater.”

“The whole church?” I said. “How tall is it?”

She sighed loudly. “St. Mark’s isn’t a church. It’s a plaza. The plaza of San Marco. Do you need me to explain what a plaza is?”

Actually, I’d known that calles were streets and hadn’t really needed an explanation of aqua alta either. But my militant ignorance on the subject of all things Italian has quickly become a game between us, one we both enjoy.

“We may need boots,” my wife ventured.

“We have boots.”

“Rubber boots. Aqua alta boots. They sound a siren.”

“If you don’t have the right boots, they sound a siren?”

She gave me a swift kick under the covers. “To warn you. That the high water’s coming. So you’ll wear your boots.”

“Who lives like this?”

“Venetians.”

“Maybe I’ll just sit in the car and wait for the water to recede.”

Another kick. “No cars.”

“Right. No cars.”

“Lou?”

“No cars,” I repeated. “Got it. Calles where the streets should be. No cars in the calles, though, not one.”

“We haven’t heard back from Bobby.”

Our old friend. Our third musketeer from senior year of high school. Long, long gone from us. She didn’t have to tell me we hadn’t heard back. “Maybe he’s moved. Maybe he doesn’t live in Venice anymore.”

“Maybe he’d rather not see us.”

“Why? Why would he not want to see us?”

I could feel my wife shrug in the dark, and feel our sense of play running aground. “How’s your story coming?”

“Good,” I told her. “I’ve been born already. A chronological approach is best, don’t you think?”

“I thought you were writing a history of Thomaston,” she said.

“Thomaston’s in it, but so am I.”

“How about me?” she said, taking my hand again.

“Not yet. I’m still just a baby. You’re still downstate. Out of sight, out of mind.”

“You could lie. You could say I lived next door. That way we’d always be together.” Playful again, now.

“I’ll think about it,” I said. “But the people who actually lived next door are the problem. I’d have to evict them.”

“I wouldn’t want you to do that.”

“It is tempting to lie, though,” I admitted.

“About what?” She yawned, and I knew she’d be asleep and snoring peacefully in another minute or two.

“Everything.”

“Lou?”

“What.”

“Promise me you won’t let it become an obsession.”

It’s true. I’m prone to obsession. “It won’t be,” I promised her.

But I’m not the only reason my wife is on guard against obsession. Her father, who taught English at the high school, spent his summers writing a novel that by the end had swollen to more than a thousand single-spaced pages and still with no end in sight. I myself am drawn to shorter narratives. Of late, obituaries. It troubles my wife that I read them with my morning coffee, going directly to that section of the newspaper, but turning sixty does that, does it not? Death isn’t an obsession, just a reality. Last month I read of the death—in yet another car accident—of a man whose life had been intertwined with mine since we were boys. I slipped it into the envelope that contained my wife’s letter, the one that announced our forthcoming travels, to our old friend Bobby, who will remember him well. Obituaries, I believe, are really less about death than the odd shapes life takes, the patterns that death allows us to see. At sixty, these patterns are important.

“I’m thinking fifty pages should do it. A hundred, tops. And I’ve already got a title: The Dullest Story Ever Told.”

When she had no response to this, I glanced over and saw that her breathing had become regular, that her eyes were closed, lids fluttering.

It’s possible, of course, that Bobby might prefer not to see us, his oldest friends. Not everyone, Sarah reminds me, values the past as I do. Dwells on it, she no doubt means. Loves it. Is troubled by it. Alludes to it in conversation without appropriate transition. Had I finished my university degree, as my mother desperately wanted me to, it would have been in history, and that might have afforded me ample justification for this inclination to gaze backward. But Bobby—having fled our town, state and nation at eighteen—may have little desire to stroll down memory lane. After living all over Europe, he might well have all but forgotten those he fled. I can joke about mine being “the dullest story ever told,” but to a man like Bobby it probably isn’t so very far from the truth. I could go back over my correspondence with him, though I think I know what I’d find in it—polite acknowledgment of whatever I’ve sent him, news that someone we’d both known as boys has married, or divorced, or been arrested, or diagnosed, or died. But little beyond acknowledgment. His responses to my newsy letters will contain no requests for further information, no Do you ever hear from so-and-so anymore? Still, I’m confident Bobby would be happy to see us, that my wife and I haven’t become inconsequential to him.

Why not admit it? Of late, he has been much on my mind.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

FREE shipping within U.S.A.

Destination, rates & speedsSearch results for Bridge of Sighs

Bridge of Sighs

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00057059896

Quantity: 14 available

Bridge of Sighs

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. 1st Edition. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # GRP64692850

Quantity: 4 available

Bridge of Sighs

Seller: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. 1st Edition. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # GRP64692850

Quantity: 2 available

Bridge of Sighs

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. 1st Edition. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 2883073-75

Quantity: 6 available

Bridge of Sighs

Seller: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. 1st Edition. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 2883073-75

Quantity: 1 available

Bridge of Sighs

Seller: Reliant Bookstore, El Dorado, KS, U.S.A.

Condition: good. This book is in good condition with very minimal damage. Pages may have minimal notes or highlighting. Cover image on the book may vary from photo. Ships out quickly in a secure plastic mailer. Seller Inventory # RDV.0375414959.G

Quantity: 2 available

Bridge of Sighs

Seller: Direct Link Marketing, Pine hill, NY, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. Dust Jacket Condition: Good. Seller Inventory # 008339

Quantity: 1 available

Bridge of Sighs

Seller: More Than Words, Waltham, MA, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. . . All orders guaranteed and ship within 24 hours. Before placing your order for please contact us for confirmation on the book's binding. Check out our other listings to add to your order for discounted shipping.7070706374. Seller Inventory # BOS-H-03j-01474

Quantity: 3 available

Bridge of Sighs

Seller: BookHolders, Towson, MD, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. [ No Hassle 30 Day Returns ][ Ships Daily ] [ Underlining/Highlighting: NONE ] [ Writing: NONE ] [ Edition: first ] Publisher: Knopf Pub Date: 9/25/2007 Binding: Hardcover Pages: 544 first edition. Seller Inventory # 2945503

Quantity: 1 available

Bridge of Sighs

Seller: Once Upon A Time Books, Siloam Springs, AR, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Acceptable. This is a used book. It may contain highlighting/underlining and/or the book may show heavier signs of wear . It may also be ex-library or without dustjacket. This is a used book. It may contain highlighting/underlining and/or the book may show heavier signs of wear . It may also be ex-library or without dustjacket. Seller Inventory # mon0001371611

Quantity: 1 available