Items related to Stepin Fetchit: The Life and Times of Lincoln Perry

Synopsis

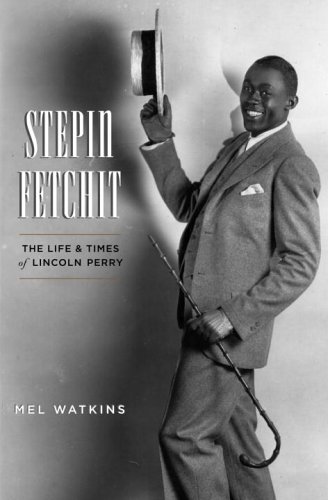

The first African American movie star, Lincoln Perry, a.k.a. Stepin Fetchit, is an iconic figure in the history of American popular culture. In the late 1920s and ’30s he was both renowned and reviled for his surrealistic portrayals of the era’s most popular comic stereotype—the lazy, shiftless Negro. After his breakthrough role in the 1929 film Hearts in Dixie, Perry was hailed as “the best actor that the talking pictures have produced” by the critic Robert Benchley.

Having run away from his Key West home in his early teens, Perry found success as a vaude-

villian before making his way to California. The tall, lanky actor became the first millionaire black movie star when he appeared in a string of hit movies as the whiny, ever-perplexed, slow-talking comic sidekick. Perry was the highest paid and most popular black comedian in America during Hollywood’s Golden Age, but his ongoing battles with movie executives, his rowdy offscreen behavior, and his extravagant spending kept him in gossip-column headlines. Perry’s spendthrift ways and exorbitant lifestyle hastened his decline and, in 1947, having squandered or given away his fortune, he was forced to declare bankruptcy.

In 1964 Perry was discovered in the charity ward of Chicago’s Cook County Hospital; he later turned up in Muhammad Ali’s entourage. In 1972 he unsuccessfully sued CBS for defamation because of a television program that ridiculed the type of characters he had portrayed. But his achievements were eventually acknowledged: in 1976 the Hollywood chapter of the NAACP gave him its Special Image Award for having opened the door for many a succeeding African American film star, and in 1978 he was inducted into the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame. In Stepin Fetchit, Mel Watkins has given us the first definitive, full-scale biography of an entertainment legend.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Mel Watkins, a former editor and writer for The New York Times Book Review, is the author of Dancing with Strangers, a Literary Guild Selection, and of the highly acclaimed On the Real Side: A History of African American Comedy. He lives in New York City.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

In the late 1800s, Key West, Florida, still bore a faint resemblance to the barren wilderness described in settlers' colorful tales about the island's fierce Calusa Indians or the marauding pirates who had kept the eighteenth-century French and Spanish pioneers at bay for decades. The four-mile-long sand and coral island had officially become part of the United States in 1826. Only ninety miles from Havana, Cuba, it was the southernmost settlement in the continental United States and still had the untamed aura of a frontier outpost. By 1860, as the nation moved inevitably toward the Civil War, it had become the wealthiest city per capita in America despite not having a rail link to the Florida mainland. At the time, its economy relied on shipbuilding, sponging, cigar packing, and the harvesting of snail, shrimp, lobster, and stone crab.

The island's prosperity was fleeting, however. Still, the mid-nineteenth-century boom along with the island's natural beauty and reputation as an exotic getaway made it a haven and magnet for adventurers, artists, eccentrics, and tourists, as well as for a growing number of West Indians for whom it was a doorway to the United States. Among the latter group were Joseph H. Perry, a skilled Jamaican cigar wrapper, cook, and would-be entertainer, and Dora Monroe, a Bahamian seamstress who grew up in Nassau. They were married in 1898 and, leaving Nassau, arrived in Key West in 1902.

In addition to being something of a womanizer and traveling man, Joseph Perry was, by many accounts, a fair hoofer, singer, and an aspiring minstrel stage performer. He was a gregarious, cocky man who took great pride in his Caribbean background and his status as a subject of the British Crown--a fact of which he regularly boasted, particularly when dealing with African Americans.

Joseph and Dora had three children. Their second child, Lincoln, would go on to far surpass his father's wildest aspirations.

Lincoln Perry was born on May 30, 1902, in Key West. He later claimed that his father named him for four presidents; his full name was Lincoln Theodore Monroe Andrew Perry. According to one account, "he was born as an American by a few hours only," since his parents arrived in the Keys just prior to his birth. His older sister, Lucille, had been born two years earlier, and his younger sister, Mary, who later changed her name to Marie, was born a year and a half later. Lincoln and his siblings rarely discussed their childhood or family life publicly, and since no personal letters or firsthand accounts related to that period have been found, the actor's early years in Key West and his adolescent years in Tampa after the family moved to the mainland are shrouded in mystery.

Apparently, Lincoln Perry did not suffer from a lack of confidence. Like many other Caribbean immigrants, the Perry family reportedly displayed an assertiveness that, at the time, was most often held in check by former African American slaves and their descendants. Years after he reigned as a Hollywood star, Perry suggested that his youthful self-esteem was derived from his Caribbean background.

"I'm a descendant of the West Indies," Perry told a reporter. "I had talent all my life." Far from being "lazy and stupid . . . the white man's fool" that many made him out to be, he insisted that he was "the first Negro militant."

It was a defense of his by-then-tainted reputation and an affirmation of pride in his West Indian heritage. Perry's attitude reflected a culturally based rift between American-born and Caribbean-born blacks that in the early twentieth century frequently sparked heated clashes.

Despite the mumbling, ostensibly cowering screen character that he later immortalized as Stepin Fetchit, Lincoln Perry displayed his aggressive racial and cultural pride in offscreen relationships with both whites and blacks throughout his career.

Ironically, when his double-talk and roundabout public statements are scrutinized, when his extravagant spending, cavalier lifestyle and frequent clashes with the producers and moguls who controlled the Hollywood studio system are put into context, Perry surfaces in sharp contrast to the image inspired by previous knee-jerk assumptions. Uneducated, but shrewdly intelligent, he parlayed his considerable talent and folk wit (the equivalent of today's street smarts) into screen stardom during a period of blatant racial oppression and intolerance that make conditions in the twenty-first-century "hood" look like a model of racial harmony and equality.

He was far deeper and much more volatile and complicated than the portrait of a shallow, ingratiating buffoon drawn by many historians and critics. Pronouncements of religious fervor aside, he was no choirboy. Hot-tempered, prone to violent outbursts, egotistical, and, at heart, a bit of a scoundrel--he was as confounding as any black star who took to the stage and screen in the twentieth century. But when the character he created on stage and in pictures is considered as a carefully molded caricature that burlesqued mainstream America's contemptuous vision of Negroes, Perry also emerges as a cagey self-publicist and brilliant comic actor. Perhaps most surprisingly, when his on-set hassles with studio executives are viewed in the context of the era's twisted racial arrangements and his pioneer achievements in the film industry are weighed objectively, he rears as a prideful, race-conscious agitator for equal treatment in the entertainment field. He was, and still is, largely misunderstood. If not quite the "militant" that he sometimes claimed, he was a sly provocateur. "I didn't fight my way in," he once said, "I eased in." At the time, it was realistically the only way of bucking the system.

Pride and Caribbean heritage aside, the racial tenor of early-twentieth-century America dictated that Perry and his family exercise some caution around white Americans. Like many American Negroes, they often resorted to a bit of subterfuge and trickery developed in Southern slave quarters as well as the West Indies--a survival tactic that would be sustained long after slaves were freed. It was perhaps best described by the old saw "Got one mind for white folks to see; 'nother for what I know is me." The tactic found its most frequent expression in what slaves had called "puttin' on ole massa." Lincoln Perry was an expert at it.

At the peak of his Hollywood stardom--when nearly every black shoeshine boy in America began copying his lazy drawl and slow, shambling gait, and motion-picture-cartoon representations of Negroes were invariably modeled on the character he created--Lincoln Perry doggedly adhered to that bit of black folk wisdom. He misled interviewers with fanciful anecdotes about his past, distorting and reshaping facts regarding his childhood as well as other aspects of his personal life in nearly all comments to the press, and, until his last years, generally bedeviled any attempt to expose the real person behind his carefully concocted public persona. For Perry the ruse was also an expression of the waggish delight he took in mocking America's middle-class mores by confounding and often outfoxing assumedly "superior" adversaries.

The rambling, circuitous accounts of his past with which he regaled reporters were often calculated misdirections, reflecting a roguish temperament and sly, double-edged wit that, despite his stature as one of America's best-known comedians, most observers were reluctant to concede he possessed. Throughout his life, Lincoln Perry remained an enigmatic, chameleonlike, conflicted figure--an entertainer whose name and reputation would assume mythic proportions, while the man behind the myth remained as illusive as a shadow. Even today, while most are familiar with the name Stepin Fetchit and may even have used it in a derogatory manner, very few have ever actually seen the actor perform onstage or in motion pictures. (Scenes in which he appeared have been deleted from most of the few movies available on tape or shown on television.)

What generally surfaced in the media was the specter of a self-indulgent profligate and malcontent whose antic conduct--much like the often outrageous stunts of latter-day comics and Bad Boys Richard Pryor and Martin Lawrence--seemed driven by some self-destructive, deep-seated internal demon. The assessment was in part correct. In addition, however, like Madonna, Howard Stern, Britney Spears, J. Lo, Paris Hilton, and many other present-day celebrities, he realized that even bad press sells--that notoriety can and often does confer power.

There is little doubt that at an early age Perry was a cutup and prankster. "Ah was terrible bright, but Ah never studied," he once told a reporter, insisting (as he commonly did with the mainstream press) that his remarks be rendered in stilted stage dialect. "Ah was a bad example. Ah was a thug, allus stealin'." Even his self-dubbed childhood nickname, "Slop Jar," suggests that early on he had an outsider's irreverent, somewhat satirical view of both himself and his life circumstances.

Still, he developed a keen interest in religion at an early age, which lead a childhood friend to insist that "Step was always a church fanatic." It was Dora Perry who initially fired that religious fervor. Unlike her husband, she was a pious woman and a devout Catholic who reportedly insisted that her children attend church regularly. Lincoln adored his mother and seems to have followed her instructions or given the appearance of doing so without much complaint. Long after her death, Lincoln's connection to the church rema...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherPantheon

- Publication date2005

- ISBN 10 0375423826

- ISBN 13 9780375423826

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages352

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Stepin Fetchit: The Life and Times of Lincoln Perry

Seller: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Very Good condition. Like New dust jacket. A copy that may have a few cosmetic defects. May also contain light spine creasing or a few markings such as an owner's name, short gifter's inscription or light stamp. Bundled media such as CDs, DVDs, floppy disks or access codes may not be included. Seller Inventory # O10P-00819

Quantity: 1 available

Stepin Fetchit: The Life and Times of Lincoln Perry

Seller: Books From California, Simi Valley, CA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. Dust Jacket Condition: Includes dust jacket. Dust jacket with some loss and tearing at the bottom edges. Cover shows minor rubbing, pages clean. Seller Inventory # mon0003103142

Quantity: 1 available

Stepin Fetchit : The Life and Times of Lincoln Perry

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 471212-6

Quantity: 2 available

Stepin Fetchit: The Life and Times of Lincoln Perry

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. Missing dust jacket; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.56. Seller Inventory # G0375423826I4N01

Quantity: 1 available

Stepin Fetchit: The Life and Times of Lincoln Perry

Seller: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.56. Seller Inventory # G0375423826I3N00

Quantity: 1 available

Stepin Fetchit: The Life and Times of Lincoln Perry

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.56. Seller Inventory # G0375423826I4N10

Quantity: 1 available

Stepin Fetchit: The Life and Times of Lincoln Perry

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.56. Seller Inventory # G0375423826I3N00

Quantity: 1 available

Stepin Fetchit: The Life and Times of Lincoln Perry

Seller: Irish Booksellers, Portland, ME, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. SHIPS FROM USA. Used books have different signs of use and do not include supplemental materials such as CDs, Dvds, Access Codes, charts or any other extra material. All used books might have various degrees of writing, highliting and wear and tear and possibly be an ex-library with the usual stickers and stamps. Dust Jackets are not guaranteed and when still present, they will have various degrees of tear and damage. All images are Stock Photos, not of the actual item. book. Seller Inventory # 10-0375423826-G

Quantity: 1 available

Stepin Fetchit: The Life and Times of Lincoln Perry

Seller: Books Unplugged, Amherst, NY, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Buy with confidence! Book is in good condition with minor wear to the pages, binding, and minor marks within 1.5. Seller Inventory # bk0375423826xvz189zvxgdd

Quantity: 1 available

Stepin Fetchit: The Life and Times of Lincoln Perry

Seller: rareviewbooks, Kensington, MD, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Dust Jacket Condition: Very Good. 1st Edition. Hardback book (338 pages) illustrated with vintage photographs. Dust jacket in protective mylar cover shows light rubbing/scuffing. Bookseller since 1995 (LL-Base2-B-Bottom-2Up-R) rareviewbooks. Seller Inventory # RVB08061901

Quantity: 1 available