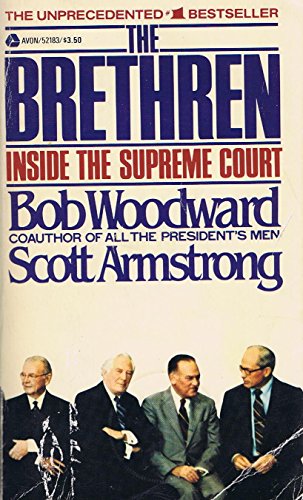

Items related to The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Earl Warren, the Chief Justice of the United States, hailed the elevator operator as if he were campaigning, stepped in and rode to the basement of the Supreme Court Building, where the Court limousine was waiting. Warren easily guided his bulky, 6-foot-1-inch, 220-pound frame into the back seat. Though he was seventy-seven, the Chief still had great stamina and resilience.

Four young men got into the car with him that fine November Saturday in 1968. They were his clerks, recent law graduates, who for one year were his confidential assistants, ghost writers, extra sons and intimates. They knew the "Warren Era" was about to end. As Chief Justice for fifteen years, Warren had led a judicial revolution that reshaped many social and political relationships in Amer-ica. The Warren Court had often plunged the country into bitter controversy as it decreed an end to publicly supported racial discrimination, banned prayer in the public schools, and extended constitutional guarantees to blacks, poor people, Communists, and those who were questioned, arrested or charged by the police. Warren's clerks revered him as a symbol, the spirit of much that had happened. The former crusading prosecutor, three-term governor of California, and Republican vice-presidential nominee had had, as Chief Justice, a greater impact on the country than most Presidents.

The clerks loved their jobs. The way things worked in the Chief's chambers gave them tremendous influence. Warren told them how he wanted the cases to come out. But the legal research and the drafting of Court opinions -- even those that had made Warren and his Court famous and infamous -- were their domain. Warren was not an abstract thinker, nor was he a gifted scholar. He was more interested in the basic fairness of decisions than the legal rationales.

They headed west, downtown, turned into 16th Street and pulled into the circular driveway of the University Club, a private eating and athletic club next to the Soviet Embassy, four blocks north of the White House. The staff was expecting them. This was a Saturday ritual. Warren was comfortable here. His clerks were less so. They never asked him how he could belong to a club that had no black members.

With his clerks in tow, Warren bounded up the thick-carpeted steps to the grill. It was early for lunch, not yet noon, and the room was empty. Warren liked to start promptly so they would have time for drinks and lunch before the football game. They sat in wooden captain's chairs at a table near the television and ordered drinks. The Chief had his usual gimlet. He was pensive. They ordered another round. Warren reminisced, told political stories, chatted about sports, and then turned to the recent past, to Richard Nixon's election. The Chief thought it was a catastrophe for the country. He could find no redeeming qualities in his fellow California Republican. Nixon was weak, indirect, awkward and double-dealing, and frequently mean-spirited. Throughout the 1968 presidential campaign, Nixon had run against Warren and his Court as much as he had run against his Democratic rival, Senator Hubert Humphrey. Playing on prejudice and rage, particularly in the South, Nixon had promised that his appointees to the Supreme Court would be different.

It was unlikely that a Nixon Court would reverse all the Warren Court's decisions. Though Justices John Harlan, Potter Stewart and Byron White had dissented from some of the famous Warren decisions, each of them had strong reservations on the matter of the Court's reversing itself. They believed firmly in the doctrine of stare decisis -- the principle that precedent governs, that the Court is a continuing body making law that does not change abruptly merely because Justices are replaced.

But as Warren and his clerks moved to lunch, the Chief expressed his frustration and his foreboding about a Nixon presidency. Earlier that year, before the election, Warren had tried to ensure a liberal successor by submitting his resignation to President Lyndon B. Johnson. The Senate had rejected Johnson's nominee, Associate Justice Abe Fortas, as a "crony" of the Presi-dent. All that had been accomplished was that Nixon now had Warren's resignation on his desk, and he would name the next Chief Justice.

Warren was haunted by the prospect. Supreme Court appointments were unpredictable, of course. There was, he told his clerks, no telling what a President might do. He had never imagined that Dwight Eisenhower would pick him in 1953. Ike said he had chosen Warren for his "middle of the road philosophy." Later Eisenhower remarked that the appointment was "the biggest damned-fool mistake I ever made." Well, Warren said, Ike was no lawyer. The clerks smiled. But Richard Nixon was, and he had campaign promises to fulfill. He must have learned from Eisen-hower's experience. He would choose a man with clearly defined views, an experienced judge who had been tested publicly on the issues. The President would look for a reliable, predictable man who was committed to Nixon's own philosophy.

"Who?" asked the clerks.

"Why don't we all write down on a piece of paper who we think the nominee will be?" Warren suggested with a grin.

One clerk tore a sheet of paper into five strips and they sealed their choices in an envelope to be opened after Nixon had named his man.

Warren bent slightly over the polished wooden table to conceal the name he wrote.

Warren E. Burger.

Three months later, on the morning of February 4, 1969, Warren Burger, sixty-one, was in his spacious chambers on the fifth floor of the Court of Appeals on Pennsylvania Avenue, almost midway between the White House and the Supreme Court. President Nixon, who had been in office only two weeks, had invited him to swear in several high-ranking government officials at the White House. When he arrived at the mansion, Burger was instantly admitted at the gate.

Nixon and Burger first met at the Republican National Convention in 1948. Nixon was a freshman Congressman and Burger was floor manager for his home-state candidate, Minnesota Governor Harold Stassen. At the next convention, four years later, Burger played an important role in Eisenhower's nomination. He was named assistant attorney general in charge of the Claims Division in the Justice Department, and in 1956 he was appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. On that famously liberal court, Burger became the vocal dissenter whose law-and-order opinions made the headlines. He was no bleeding heart or social activist, but a professional judge, a man of solid achievement.

Now at the White House, the ceremonial swearings-in lasted only a few minutes, but afterward the President invited Burger to the Oval Office. Nixon emphasized the fact that as head of the Executive Branch he was deeply concerned about the judiciary. There was a lot to be done.

Burger could not agree more, he told the President.

Nixon told him that in one of his campaign addresses he had used two points from a speech Burger had given in 1967 at Ripon College in Wisconsin. U.S. News & World Report had reprinted it under the title "What to Do About Crime in U.S." The men agreed that U.S. News was the country's best weekly news magazine, a Republican voice in an overwhelmingly liberal press. Burger had brought a copy of the article with him.

In his speech Burger had charged that criminal trials were too often long delayed and subsequently encumbered with too many appeals, retrials and other procedural protections for the accused that had been devised by the courts.

Burger had argued that five-to-ten-year delays in criminal trials undermined the public's confidence in the judicial system. Decent people felt anger, frustration and bitterness, while the criminal was encouraged to think that his free lawyer would somewhere find a technical loophole that would let him off. He had pointed to progressive countries like Holland, Denmark and Sweden, which had simpler and faster criminal justice systems. Their prisons were better and were directed more toward rehabilitation. The murder rate in Sweden was 4 percent of that in the United States. He had stressed that the United States system was presently tilted toward the criminal and needed to be corrected.

Richard Nixon was impressed. This was a voice of reason, of enlightened conservatism -- firm, direct and fair. Judge Burger knew what he was talking about. The President questioned him in some detail. He found the answers solid, reflecting his own views, and supported with evidence. Burger had ideas about improving the efficiency of judges. By reducing the time wasted on routine administrative tasks and mediating minor pretrial wrangles among lawyers, a judge could focus on his real job of hearing cases. Burger also was obviously not a judge who focused only on individual cases. He was concerned about the system, the prosecutors, the accused, the victims of crime, the prisons, the effect of home, school, church and community in teaching young people discipline and respect.

The President was eager to appoint solid conservatives to federal judgeships throughout the country. As chairman of a prestigious American Bar Association committee, Burger had traveled around the country and must know many people who could qualify. The President wanted to appoint men of Burger's caliber to the federal bench, including the Supreme Court. Though the meeting was lasting longer than he had planned, the President buzzed for his White House counsel, John Ehrlichman.

Ehrlichman came down from his second-floor office in the West Wing. Nixon introduced them. "Judge Burger has brought with him an article that is excellent. Make sure that copies are circulated to others on the White House staff," Nixon said. He added that Burger had constructive, solid ideas on the judicial system as well as for their anticrime campaign. Judge Burger was a man who had done his homework. "Please make an appointment with him to talk," the President said, "and put into effect what he ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherAvon Books

- Publication date1996

- ISBN 10 0380521830

- ISBN 13 9780380521838

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages558

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.50

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0380521830

The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0380521830

The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0380521830

The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0380521830

THE BRETHREN: INSIDE THE SUPREME

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.65. Seller Inventory # Q-0380521830