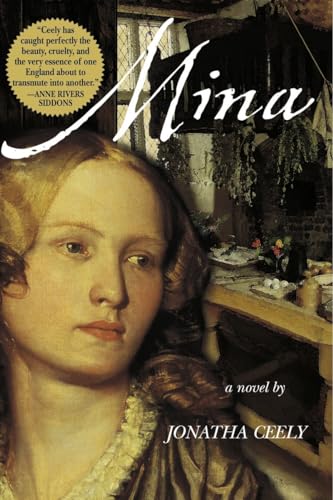

Items related to Mina: A Novel

Amid the lush fields and gardens of an English estate, in a kitchen where every meal is a sumptuous feast, a young servant called Paddy anxiously hides her true identity. Using coal soot and grease, she conceals her flaming head of red hair and covers her body, desperate to keep the job she needs to survive. But the girl, whose real name is Mina, cannot conceal from herself the pain of her past or the beauty of an Ireland she remembers with love and grief—until she meets a man who convinces her to trust him, a man hiding sorrows of his own.

To the mysterious Mr. Serle—the estate’s skilled and quiet chef—Mina dares to confess her true identity and reveal a shattered past: her flight from the blighted fields of her homeland to the teeming streets of Liverpool...her memories of the family she lost and dreams for the future. And as Mina and Mr. Serle begin to know each other, an extraordinary journey begins—a journey of faith and identity, adventure and awakening, that will alter the course of both their lives.

The sights and sounds of nineteenth-century England come vividly to life in Jonatha Ceely’s magnificent novel, a tale that explores the intricate relationship forged by two people in hiding. Moving and unforgettable, Mina is historical fiction at its finest—a novel that makes you think, feel, and marvel...until the last satisfying page is turned.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Someone asks: What country, friends, is this? No answer. I open my eyes with a start. In the dim early-morning light, the world returns around me. I lie nestled in straw in the stable loft of a country estate. I look out a dormer window toward the soft hills that rise in a low ridge between the estate and the nearby village.

Below me the horses shift in their stalls. Their safe smell and their heat rises to me. It is dawn, and the sounds of the yards and the house awakening will begin in a few moments. This is the moment of stillness before the lark rises toward the rosy light raying up from the eastern horizon, toward the zenith of the clear spring sky.

My work begins as the lark flies up, singing from its meadow nest to greet the sun. I too rise. I begin not with a hymn to nature but with a visit to the outhouse, ablutions under the pump, a quick ordering of my garments.

Then I attend to the horses. They need water, clean straw, and grooming. But first I have something else to do.

I have a dream that recurs. It came to me again last night. I walk from the door of our croft into the field that slopes to the south. The land is green, green, green, like a velvet gown laid over a curving body. In my dream I tread lightly on the soft surface. I feel the spring of grass beneath my bare feet. As I pace down the slope of the field, I feel the warmth of the sun on my face and arms. All is pale blue above, green below, and a fresh wind blowing. I notice something growing in the field. Loaves of bread, golden-crusted. It is as if the corn had grown, been harvested, thrashed, ground, kneaded, baked all in a night—as if the bread grew ready to my hand and mouth directly from the earth. In my dream I smell the yeasty bloom and fall to my knees, mouth watering, guts cramped with hunger. I am eager to pluck and eat these magic mushrooms, brown-gold buttons on the green velvet field. I lay my hands reverently on a loaf and find that I hold stone. Frantic, I rise and run about the field from seeming loaf to seeming loaf. All stone and heavy beyond bearing.

I stumble, weeping, down the slope, and in that sudden translation of dreams find myself in a dug field. A man in ragged clothing stoops over his spade; his face is averted from me and his lowered head is covered with a shapeless blob of felted hat. He looks familiar and yet I cannot put a name to him. He turns the earth, stoops his back into the weight, lifts brown clumps from the soil—potatoes. Here is food, I think; not crusty, fragrant bread but gray flesh formed under dark loam. This man will share with me a potato or two, and I will find green herbs in the field and feed my brother. I hurry toward the man and stand beside him. My heart fails me, for here again are stones. His face turned from me, he delves stone after stone from the ground, brushes away dirt and sets the stone on a rising heap. A cairn is growing in my dream, a monument, a funeral pile. I stoop to see the face of the man who digs. His blue eyes burn with fever. His eyebrows are thick and red. His cheeks are gaunt with hunger, yet glazed with the red-gold stubble of his rough beard. This is my father. He does not speak. My tongue is thick in my mouth, my throat burns. I cannot make a sound. It would not matter if I could; I know he would not hear me.

I turn to look back to the house at the top of the rise. It is tiny in the distance. I have come much farther than I thought. I turn my steps along a path. The green grass lies to my right, the spaded soil to my left. My father will not, cannot, speak to me, for he is dead. I think that I will go back to the house and find my brother. The house is a white toy in the distance, the sky is blue and far above. I am filled with a sense of urgency.

Then, as always, I awaken in a strange country. Above the place where I nest at night in the barn loft, I have rigged a bag that swings away from the beam on a thin string. The string is enough to hold the bag, yet not thick or strong enough to give passage to the mice that might forage here. I let the bag down and check its contents. The mug and the spoon are there and my brother’s jacket, folded carefully. The bag would be limp with just those three things, but hard bread packs the cloth too. Fresh bread would mold, flour would sift away. The cook sets out this dry bread for the field hands; for three mornings now, I have managed to filch some. Why I do so, I do not know. There is food enough here at the kitchen door for all the outdoor workers. Even so, I keep this private store. I count the brown-gray squares. Six now, put away against the day of need. I will not eat of this, not even nibble on a corner to taste it. It will not matter if a little mold grows on this bread; that is easily scraped away, the biscuit boiled in water to a sticky dough. This will suffice as food. And my store is secret; I will not be called to share it until I find my brother. When the day of need comes, as come it will, I will be ready. I hoist my cache again to safety and begin the day.

It comforts me to groom the horses. I lead the black, Sultan, out of his stable into the sunshine of the back courtyard, fasten his lead to the iron ring in the wall, and wield the comb until his flanks shine and my arms ache.

As I finish with Sultan, the kitchen maid who peels the vegetables, cleans the pots, and helps the cook as he requires comes out the kitchen door. I have spoken to her just once in the three mornings I have risen here.

Yesterday, she handed me a chunk of brown bread and a wedge of cheese and said, “Here, Paddy, I don’t suppose you saw such food as this at home.”

“No,” I said, “not since two years ago. They are starving at home.” She did not answer that.

Today, she has her hair tied up in a fancy green ribbon, her skirts down at her ankles, not kilted up as she wears them when she is working. She carries a bundle under her arm.

“Good morning, Mary,” I say respectfully, keeping my voice low. “Are you off to the village so early?”

“Indeed, I am,” she says, tossing her head in her saucy way. Her face is pudding-plain and marked by smallpox besides, yet her blue eyes are clear lake-blue and fringed with long lashes. “Indeed I am, Paddy. Off to the village and beyond.” She winks at me, fluttering her black lashes down to her pox-scarred cheek.

“Beyond?” I ask, puzzled by her way of speaking and her new manner. She seems impertinent and yet fearful of her own boldness. It frightens me that she might be doing something that will involve me in a wrong.

“Beyond, indeed,” she asserts. “I’m off across the hill to the village and the stagecoach for London town.”

“London?” I feel quite stupid.

“London?” she mimics my Irish speech and my bewilderment. “Yes, London. I had a letter yesterday. My sister has a place for me in a great house, a maid’s place, sweeping and dusting the fine things. Mr. Serle will have to find someone else to shell his peas and scrub his pots. Or do it himself, the black foreigner.”

“Oh.” I can think of nothing to say to this Mary I have never seen before, this bold girl who was hiding all the time inside the lazy kitchen scullion with her straggling hair and dirty skirts.

“Oh?” says Mary. “All you have to say is ‘Oh’? You Irish are as stupid as they say.”

I want to say that I am not stupid, just surprised by the change in her. She looks almost clean in her traveling-to-London clothes. But I know it is wiser to hold my tongue. “Well, good-bye, Mary,” I say. “Godspeed your journey.”

“I’m away,” she says and hurries out the gate.

And Godspeed to me too, I say to myself under my breath. There will be a place in the kitchen to fill today. I wonder whether Mr. Serle, the black foreigner, will be angry when he learns she is gone. I have glimpsed him walking in the kitchen gardens in the morning and heard him speaking to the gardeners. I do not catch his words when I listen, only a murmur of sound. He is not a man who raises his voice. Where does he come from? I wonder. He is not so black, I think. I have seen darker in Ireland even, and in Liverpool for certain.

I lead Sultan out to the paddock behind the stable. The master will ride this morning as he does every morning. I lead out the gray mare, Gytrash. If the master’s lady does not ride her, I will exercise her, following the master in a lazy loop down to the path along the river, across the meadow by the road up to the ridge of hills, and then down along the river again to the copse of great oaks, and, finally, back across the meadows to the stable yard. I hope the lady will be busy with the house today. I love to ride. The master does not speak to me, and I am free to move with the horse and to think of my father and my brother who loved horses and raced them and wagered on them and laughed when they won and drank up the prize money to my mother’s despair. But she laughed too and said that it was all gravy money anyway and who could not love the beauty of a clean race. And when they lost, they had a pint for consolation and groomed the horses for longer even and whispered to them to run better next time.

As I run the currycomb down the dappled flank of Gytrash, I dream of the past. Gytrash means ghost; Mr. Coates, the stable master, told me. As I curry her, I think of the past. I think of the dark bay horse I groomed for my father, the dreams of horses my brother told me as we did the work on the farm. Gytrash brings my ghosts to me each morning, and for that I am grateful. I have nothing now except my ghosts, and the gold ring my mother gave me sewn into my shirttail, my brother’s riding boots, and the bag of bread I have saved in the loft.

The clothes I stand in and my brother’s boots. The boots he was taking to America. His boots, which are too big, I stuff with straw before I put them on to ride. They hardly show the water stains that marred them; I have rubbed and waxed them until they shine.

Mr. Coates will not allow me, or anyone who works for him, to ride barefoot. I have no proper shoes yet. Working in the yard, I must go barefoot, for shod in the boots, I would trip over myself. Also, the boots are my brother’s good riding boots. I will not wear them to muck out stables. His ordinary boots are gone with him. I keep his riding boots well for his return.

Gytrash goes into the paddock with Sultan, stepping daintily and then lowering her head to crop the grass. I close the gate and return to the stable for the pony. I am beginning to feel the day growing as the sun’s warmth strengthens. Once the fat pony is brushed down, I will muck out the stables and then wash myself again and seek brown bread and a mug of ale at the kitchen door.

Long after I have eaten my breakfast in the stable yard, the gentry will rise and go to their meal. Soon after that, word will come down to Mr. Coates that the horses are to be saddled for the morning ride. Later, I will polish tack and fill the water pails. I am slowly becoming accustomed to the rhythm of this place. I am beginning to feel safer here.

The cook, that dark-haired man to whom I have never spoken, is leaning against the dairy wall across from the kitchen door. He turns his face into the sun as if he would warm himself. He raises a hand in casual greeting to me as I go toward the stable again. I raise a hand in return. I wonder if he knows yet that Mary has gone away.

The pony lowers its head and swings it sideways at me as I lead him from his stall. He will nip my arm if I am not careful. I do not like this fat brown animal. He stands no more than my shoulder height at his neck. When a child or a young lady is perched on his broad back, the animal is docile enough. The halter and the lead are what annoy him—especially in the early morning. Later in the day, when he has waddled about the pasture and been exercised, he seems happier.

I set to work with the currycomb. Mr. Coates comes through the gate and across the yard. He lives in a cottage down the lane, away from the great house and close to the chapel.

“Morning, Paddy,” he says in his gruff way.

“Good morning, sir,” I respond respectfully. He makes me uneasy, although I know that is not sensible. After all, he gave me a job when I arrived here just three days past, with nothing to introduce myself but a note with his name written on a sliver of paper, my claim to know his niece, and my assertion that I am good with horses.

Mr. Coates slaps the pony on the neck. The pony, startled, sidles toward me. I leap away. Mr. Coates stands stock-still, his fists on his hips.

“Mr. Coates,” I exclaim, “sir!”

“You handle the beast well enough, Paddy,” says Mr. Coates. The pony reaches its neck toward him, its lips drawn back and its yellow teeth bared. Mr. Coates reaches out to catch the bridle. I know he will jerk the pony’s head down to discipline it.

“Comb out and then braid his mane up today,” says Mr. Coates, jerking the pony’s head around so he can look at its rough mane. “And exercise him well. They say that one of the guests, a timid lady, might wish to ride this afternoon. And clean yourself up too. Douse your head under the pump.”

“Yes, sir,” I say, moving close in again to the beast’s rear quarter with the comb in my hand. My heart pounds in my chest.

Mr. Coates slaps the pony’s neck again, and the nervous beast stamps. This time I am not quite quick enough. The pony’s rear hoof catches the side of my left foot. I feel as if I have been bitten. I think I hear the crunch of bone.

I stagger back and sit on the mounting block, cradling my foot in my two hands. No tears, I tell myself, no tears.

“Let me see that,” says Mr. Coates. He grasps my foot roughly and twists it. I cannot help myself. I cry out.

“It is broken, and it is swelling already,” he says. “You will never get a boot over that. And you cannot exercise these horses or ride with the master barefoot.”

“I can,” I assert, but inside I feel hopeless. Perhaps I could manage to mount Gytrash, but I know I can never ride and control her with my foot hurting like this. “I have ridden with far worse injuries,” I claim.

“No, lad, you will have to go. You are puny as it is, and with this injury I cannot trust a spirited horse to you. Remember that I took you for a few days on trial only.” The stableman shrugs, looks sorry, turns away from me. “There’s work in Milford, no doubt, for a willing boy with a lame foot.”

I feel the tears start to come. “I can groom the horses even if I can’t ride out to exercise them,” I protest. “I can throw down hay from the loft.”

“I must have an exercise boy,” Mr. Coates maintains. “I must have a lad decently outfitted to ride with the master and the gentry.” There is something in his voice that tells me he is not truly sorry to have found a reason to send me away.

The man standing in the sun by the garden wall walks down the courtyard toward us. “What is the quarrel here?” he says. His voice is low and his accent strange to me. Not the country, not London, but some other place.

“No quarrel, Mr. Serle.” Mr. Coates seems easygoing; he does not sound offended. “Paddy here has been careless. He has let the pony step on his foot. He won’t walk or ride for the week or even two. I cannot keep him useless to me all that time.”

“He looks well enough,” the dark man says, staring me up and down. His expression is neutral. He neither smiles nor frowns.

“I am well,” I say. “I can do the work.”

“Draw two pails of water and carry them to the stable door.” Mr. Coates is looking not at me but at the other man.

I limp over to the stable to fetch the pails. I put my weight down on the heel only. The movement pains me, but...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherDelta

- Publication date2005

- ISBN 10 0385336888

- ISBN 13 9780385336888

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages336

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Mina: A Novel

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0385336888

Mina: A Novel

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0385336888

Mina: A Novel

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0385336888

MINA: A NOVEL

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.55. Seller Inventory # Q-0385336888