Synopsis

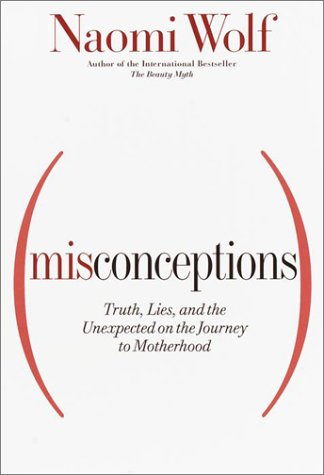

Not since The Beauty Myth has Naomi Wolf written such a powerful and passionate critique of American culture, this time, focusing on the hidden costs and vested interests surrounding pregnancy and birth in America.

While in the grip of one of the most primal, lonely, sensual and in the same ways, physically dangerous experiences they are likely to undergo, American women, Wolf argues, are offered condescending advice and damaging misconceptions about the nature of pregnancy, birth and new motherhood.

Wolf’s own first experience with pregnancy and motherhood took her aback, profoundly challenging her most basic assumptions about feminism, the nuances of abortion, and the easy expectations of freedom and equality that women of her generation hold.

In a narrative that follows the nine months of pregnancy and the first few months of early parenthood, Misconceptions illuminates the conflicting feelings of inadequacy, fragility, and even anger that so many women experience along with their sense of anticipation and joy. So often these feelings go unvoiced because of women’s fears of being seen as a “bad” mother. Wolf describes her own difficult path to first-time motherhood, and in doing so, criticizes the failure of the medical establishment to provide pregnant women with a safe, effective, and emotionally-supportive environment in which to labor. She shares riveting stories of postpartum disillusionment, as well as discloses the relationship struggles that even the most committed of couples fall into when faced with the demands of new parenthood.

In a dramatic interweaving of personal revelations and social commentary, Wolf shows that despite its much-touted reverence for families, American businesses and society make few concessions to the emotional and economic needs of new parents and, in fact, place extraordinary pressures on them.

Her conclusions, delivered with unflinching honesty, provide a telling and candid account of the journey to motherhood in America today.

Misconceptions is sure to spark intense debate over the myths and expectations that underlie contemporary pregnancy and birth, as well as about how we can better offer mothers what they truly need.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Naomi Wolf is the author of the best-selling The Beauty Myth, which helped to launch a new wave of feminism in the early 1990’s and was named one of the most significant books of the twentieth century by the New York Times; and more recently, Fire with Fire and Promiscuities. She lives in New York City with her family.

From the Back Cover

“Ultimately, Misconceptions offers the possibility of a freer, more compassionate road to parenthood for women and men” -Peggy Orenstein, author of Flux

“‘Misconceptions’ documents a . . . subtle psychological journey. . . . Wolf’s description of her own anguish and uncertainty can be as nuanced as good fiction.” —The New York Times Book Review

“Essential reading.” —Elle

“By laying bare one truth after the next–emotional, spiritual, psychological, pragmatic–this invaluable book gives women and their partners the information they so desperately need to make it through intact.”–Andrew Solomon, author of The Noonday Demon

“Combines intimate experience and expose reporting. . . . Everyone who is giving birth or getting health care should read this book.” —Gloria Steinem

From the Trade Paperback edition.

From the Inside Flap

Not since The Beauty Myth has Naomi Wolf written such a powerful and passionate critique of American culture, this time, focusing on the hidden costs and vested interests surrounding pregnancy and birth in America.

While in the grip of one of the most primal, lonely, sensual and in the same ways, physically dangerous experiences they are likely to undergo, American women, Wolf argues, are offered condescending advice and damaging misconceptions about the nature of pregnancy, birth and new motherhood.

Wolf s own first experience with pregnancy and motherhood took her aback, profoundly challenging her most basic assumptions about feminism, the nuances of abortion, and the easy expectations of freedom and equality that women of her generation hold.

In a narrative that follows the nine months of pregnancy and the first few months of early parenthood, Misconceptions illuminates the conflicting feelings of inadequacy, fragility, and even anger that so many women experience along with their sense of anticipation and joy. So often these feelings go unvoiced because of women s fears of being seen as a bad mother. Wolf describes her own difficult path to first-time motherhood, and in doing so, criticizes the failure of the medical establishment to provide pregnant women with a safe, effective, and emotionally-supportive environment in which to labor. She shares riveting stories of postpartum disillusionment, as well as discloses the relationship struggles that even the most committed of couples fall into when faced with the demands of new parenthood.

In a dramatic interweaving of personal revelations and social commentary, Wolf shows that despite its much-touted reverence for families, American businesses and society make few concessions to the emotional and economic needs of new parents and, in fact, place extraordinary pressures on them.

Her conclusions, delivered with unflinching honesty, provide a telling and candid account of the journey to motherhood in America today.

Misconceptions is sure to spark intense debate over the myths and expectations that underlie contemporary pregnancy and birth, as well as about how we can better offer mothers what they truly need.

Reviews

In her latest work, the author of the bestselling The Beauty Myth and other titles attempts to employ her fiercely confident and uncompromising, rip-the-lid-off style to tell the painful truth of motherhood in contemporary America. Interweaving personal narrative and reportage and pouncing with particular vehemence on what she considers to be the dumb, patronizing misinformation in the bestselling guidebook What To Expect When You're Expecting Wolf reveals that birth in this country is often needlessly painful. In a portentously dramatic tone, she describes how difficult and lonely it can be to care for a child and to be a working mother. Indeed, Wolf finds new motherhood so difficult that it has rocked her celebrated feminism. "Yet here we were," she concludes "to my horror and complicity, shaping our new family structure along class and gender lines daddy at work, mommy and caregiver from two different economic classes sharing the baby work during the day just as our peers had done." Wolf says little here that hasn't been said before in books like Jessica Mitford's The American Way of Birth and Ann Crittenden's The Price of Motherhood. What stands out with embarrassing clarity is her emphasis on the sufferings of a privileged minority. In prose that often lapses into purple, Wolf describes the "savagery" of breastfeeding and the unsheltered wilderness of suburban playgrounds. This work is so unoriginal in its social critique and so limited in its portrayal of the hardships endured by mothers and children and families in this country that it comes across as a weirdly out-of-touch bid for personal attention rather than a genuine expos‚. It is likely to alienate all but the newest and most sheltered mothers.

Copyright 2001 Cahners Business Information, Inc.

Steingraber turns to embryology to follow the growth and development of the child she is carrying. While describing the intricacies of fetus development with lyrical prose, she notes a heightened awareness of environmental hazards that threaten the unborn. Our industrial society produces toxic substances that can cross the placenta and appear in breast milk. She issues a wake-up call in the tradition of Rachel Carson as she welcomes her daughter, Faith, into the world. Both of these books are excellent companions to mainstream pregnancy guides such as What To Expect When You're Expecting (Workman, 1996). Highly recommended for all collections. [Misconceptions was previewed in Prepub Alert, LJ 6/1/01; for an interview with Wolf, see p.225.] Barbara M. Bibel, Oakland P.L., C.

- Barbara M. Bibel, Oakland P.L., CA

Copyright 2001 Reed Business Information, Inc.

The famous feminist author of The Beauty Myth (1991) came face to face with her own staunch beliefs about womanhood when she discovered she was pregnant. Wolf and her husband, like many other first-time parents, were thrilled to be expecting, and they began researching the many aspects of pregnancy, childbirth, and parenthood, starting with the staple What to Expect When You're Expecting (by Arlene Eisenberg and others). Finding this cheery guide too simplistic and often condescending, Wolf began her own journey for information, but she was startled to discover the utter lack of compassion from the medical profession. It wasn't until after the birth of her daughter--and a traumatic birth, at that--that Wolf realized she was not the only woman who felt isolated and insulted by the way society treats expectant mothers. Thankfully, Wolf offers a few rays of hope by unveiling some women's positive experiences with emerging alternative-childbirth options. Expect controversy but also expect demand. Mary Frances Wilkens

Copyright © American Library Association. All rights reserved

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

First Month: Discovery

For us, how did it start?

In an improbable place. My husband and I were surprised ourselves at our surroundings: in Italy, in a farmhouse outside of Todi, a Renaissance town made of stone the color of baked bread.

We felt in those surroundings a bit like Twain's Connecticut Yankees in King Arthur's court--except that in this case the court was a wedding celebration of a friend of ours whose fiancee was the doyenne of a certain group of druggie glitterati.

The wedding preparations that we watched from the sidelines involved a ragtag carnival of New York's disaffected, pale young people with dark sunglasses who populated the edges of the art world. The old sweetness of the beds of lavender and dusty thyme, and the bending olive trees, made strange contrast with the lounging, cattily gossiping bone-thin hangers-on to the wedding party. Everyone seemed still sweaty from the plane trip and acrid-smelling from too many Marlboro Lights.

Behind the small veranda where we sat, louche ex-models were making pasta in the kitchen, dressed in black bikinis and the white high-heeled hiking boots that were having a brief vogue. They were chopping fresh basil on a century-old slab of white, gray-veined marble. The groom, a rakish young attorney, paced the sloping lawn where the ceremony would be held, looking pleased and scared.

During a lull in the conversation, I gazed at my coffee and then at the line of the distant hills. A guest at the wedding, a part-time photographer or a gallery employee or a curator, with lank overprocessed blond hair and sharp features-a woman who had said nothing remarkable in my hearing for three days-suddenly leaned over toward me. She looked with a surprising compassion into my eyes and, still smoking ravenously, said, with absolute conviction:

"You're pregnant."

Was this some sort of conversation starter? Was this the New Age ramblings of someone who did not have much to say without resorting to the faux intuitive?

Nonetheless, something was going on. Was my cycle disturbed by travel? By the rich food we'd been eating? By the medicine I was taking to ease a sore knee?

When I went to wash my face some time later, my eyes in the mirror looked like nothing I'd ever seen before: yellowish and blurred, as if I were drunk. It must have been that which the wedding guest had seen. I thought maybe this had been caused by too much red Montepulciano wine, by jet lag, by anything, I half-prayed, but that thing.

After the pied-piper band scattered to make its way back across the ocean to Soho, my husband and I stayed on for a week to see a little of the country. But even as I waited, day by day, the question always at the back of my consciousness as we went sightseeing or napped in our high, white-plastered rooms, I felt something indisputable: a sickness in my gut. It was a kind of nausea that was entirely new to me: it had a richness to it, as if I had gotten sick by ingesting pure gold. If a mountain of sweets had been touched by Midas, I felt, that's what I had in my belly.

Ordinarily, when I've had scares, I've felt panic. This time, though, I felt far away from it. Every time I realized I could indeed be pregnant, I experienced, in spite of myself, a little thrill of joy.

We were in Perugina, the town of candy. There were whole streets devoted to varieties of one kind of nougat made from an ancient recipe. And still I felt that sick sweetness, surrounded by sweetness.

We asked a pleasant young woman pharmacist for a pregnancy kit. She leaned over very patiently and showed us the instructions in Italian, a language we did not understand at all: "Questa . . ." she said, speaking as if to a two-year-old and pointing at a picture of the strip with one line, "SI. Questa. . . ." she said, pointing to a picture of the strip with two lines: "NO." I recall a sense of absolute peace coming over me as we left with the packet in a small brown bag; a sense of fatalism; something that people in my cohort scarcely ever feel--a sense of events moving beyond one's control.

What will happen will happen, was something like the thought. Or even: What will happen has already happened.

When we found out for sure, we were in a neighboring town, a smaller one. The town was built up around a dark, cool bath that a medieval woman saint used to swim in.

We found out and gazed at one another--"in wild surmise." Then we reacted very differently. My husband needed to go for a run--and think; and I needed to sit still and not think. Male and female, after our first amazement, we reacted spontaneously, like different elements.

I went out to sit by myself, perfectly, uncharacteristically becalmed.

I sat on an old stone bench looking out over a deep, green, shadowy valley that the sun had saturated for days without number. My first thought was this: Thank God I have traveled a lot in my life when I was young.

Because now I will have to sit still.

For who knows how long.

* * *

For fifteen years birth control had never failed me; and then, when my heart and body longed for a baby, when I was newly married, when it was finally safe--birth control failed me. Was this baby "planned"? Technology did not plan this pregnancy; indeed, technology planned against it. It seemed my heart planned it. Like many women I would hear from later, I had the strong intuition that will and longing had somehow altered chemistry; that mother love, the mother wish, had created a different alchemy, more powerful than the alchemy of the lab or the product trial.

We returned to Washington, D.C., where we were living in a small apartment in an old leafy neighborhood. I soon lost the quiet confidence I had briefly felt, newly pregnant on a bench in the Italian sun. Being home meant that I was inducted into a medical system that had very clear expectations of me--but little room for me to negotiate my expectations of it.

I visited a highly respected practice and endured a brisk, efficient pelvic exam with a cold-handed ob-gyn. His focus on me (or, I should say, "me," since his attention seemed focused on an interchangeable "it") was entirely waist-down. I felt slightly irrational for being bothered by his manner. Clearly I was in good medical hands. Did it really matter that the man did not look me in the eye? Did it matter that the doctor, a heavyset fellow with a middle-European accent, had reminded me of Helmut Kohl attending impatiently to a routine briefing? When we left, I had the sad, sinking feeling of someone trying to summon the energy to do something creative within a rigid regime.

A few weeks later I met another of the obstetricians in the practice. The obstetricians rotated their duties. I wondered at the reason for this--did it help them to keep a professional distance? Was that good?

I was glad to know that this one would be a woman. I had a lot of questions to ask. I had just finished reading Jessica Mitford's The American Way of Birth, a terrifying expose of medical intrusiveness in the birthing profession: soaring C-section rates, needless forceps intervention, routine epidurals and episiotomies, the technique of forcing the labor into a preordained bell curve-all practices that were performed far less frequently in Europe, and Europe had better outcomes.

My obstetrician that day was a glamorous woman with perfectly coifed suburban hair, a tennis-toned figure, and an office full of gleaming French Provioncial furniture. Her husband was a powerful local developer; I had seen their picture in the society pages. She gazed at me as if she were the president of a one-woman bank and I was a high-risk loan applicant. My husband and I sat opposite her mighty desk, petitioning.

She said curtly that I could go ahead and ask my questions.

"Can you tell me what the C-section rate for our hospital is?" I asked politely, respectful and curious.

She looked uncomfortable. "I think it's about thirty per cent, but that figure is misleading. A number of those C-sections are high-risk. Since the hospital gets the difficult cases, you can't judge from the number with any accuracy."

I had read that this was a standard response, one of many that made it hard for parents to judge C-section probabilities of any given hospital for themselves. I tried another tack:

"What about the rate for this OB-GYN practice?"

She flushed. "Maybe nineteen percent. I'm not exactly certain. But all of the C-sections we perform are done for a good reason, you can rest assured."

"Is there any way for us to find the figures? Does the practice keep records?" In my innocence, I thought perhaps she didn't understand where she could find the data I was requesting. I had not yet done the kind of reading that I would do long afterwards, so I did not yet know that an ideological war was being waged over births in mainstream hospitals. I did not know that these seemingly innocent questions of mine were, to my obstetrician and virtually everyone else in the medical profession I would encounter on the way to the birth, part of a minefield of litigation, politics, vested interests, money, and beliefs about who holds the power over the delivery room. I thought I was asking about a biological process. More fool me.

"Believe me," she replied heatedly, like a politician on message, "an OB-GYN at this practice is only going to recommend a C-section if it is the medically called-for solution to a problem."

"Okay . . . , " I said, taking a silent step back at her defensiveness. I saw I was going to get nowhere further with that question.

"Well . . . what is the rate of epidurals?" I continued.

At this she laughed at me outright, an angry laugh. A note of casual contempt for my naivete filtered through her otherwise well-bred, well-modulated voice. "Everyone wants an epidural. You may t...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

Other Popular Editions of the Same Title

Search results for Misconceptions: Truth, Lies, and the Unexpected on...

Misconceptions: Truth, Lies, and the Unexpected on the Journey to Motherhood

Seller: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00053722035

Misconceptions: Truth, Lies, and the Unexpected on the Journey to Motherhood

Seller: More Than Words, Waltham, MA, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. A sound copy with only light wear. Overall a solid copy at a great price! Seller Inventory # BOS-M-12e-01588

Misconceptions: Truth, Lies, and the Unexpected on the Journey to Motherhood

Seller: Once Upon A Time Books, Siloam Springs, AR, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Good. This is a used book in good condition and may show some signs of use or wear . This is a used book in good condition and may show some signs of use or wear . Seller Inventory # mon0000616237

Misconceptions: Truth, Lies, and the Unexpected on the Journey to Motherhood

Seller: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Very Good condition. Very Good dust jacket. A copy that may have a few cosmetic defects. May also contain light spine creasing or a few markings such as an owner's name, short gifter's inscription or light stamp. Seller Inventory # X05A-02788

Misconceptions: Truth, Lies, and the Unexpected on the Journey to Motherhood

Seller: Once Upon A Time Books, Siloam Springs, AR, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Acceptable. This is a used book. It may contain highlighting/underlining and/or the book may show heavier signs of wear . It may also be ex-library or without dustjacket. This is a used book. It may contain highlighting/underlining and/or the book may show heavier signs of wear . It may also be ex-library or without dustjacket. Seller Inventory # mon0001364762

Misconceptions: Truth, Lies, and the Unexpected on the Journey to Motherhood

Seller: Half Price Books Inc., Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Seller Inventory # S_403349594

Misconceptions: Truth, Lies, and the Unexpected on the Journey to

Seller: Hawking Books, Edgewood, TX, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Very Good Condition. Five star seller - Buy with confidence! Seller Inventory # X0385493029X2

Misconceptions: Truth, Lies, and the Unexpected on the Journey to Motherhood

Seller: Half Price Books Inc., Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Seller Inventory # S_322646045

Misconceptions: Truth, Lies, and the Unexpected on the Journey to Motherhood

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: As New. No Jacket. Pages are clean and are not marred by notes or folds of any kind. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G0385493029I2N00

Misconceptions: Truth, Lies, and the Unexpected on the Journey to Motherhood

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: As New. No Jacket. Pages are clean and are not marred by notes or folds of any kind. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G0385493029I2N00