Items related to Postcards from the Brain Museum: The Improbable Search...

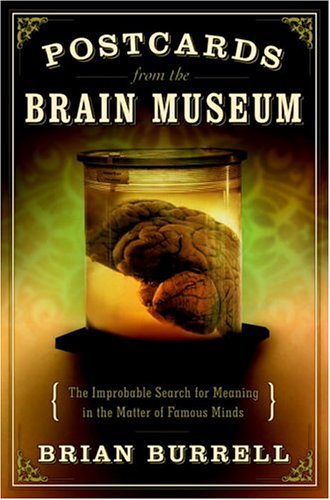

Postcards from the Brain Museum: The Improbable Search for Meaning in the Matter of Famous Minds - Hardcover

Synopsis

What makes one man a genius and another a criminal? Is there a physical explanation for these differences? For hundreds of years, scientists have been fascinated by this question.

In Postcards from the Brain Museum, Brian Burrell relates the story of the first scientific attempts to locate the sources of both genius and depravity in the physical anatomy of the human brain. It describes the men who studied and collected special brains, the men who gave them up, and the sometimes cruel fate of the brains themselves.

The fascination with elite brains was an aspect of the scientific mania for measurement that gripped the Western world in the mid-nineteenth century, along with a passionate interest in the biological basis of genius or exceptional talent. Many leading intellectuals and artists willed their brains to science, and the brains of notorious criminals were also collected by eager anatomists ghoulishly waiting in the execution chamber with a bag full of sharp metal tools.

Focusing on the posthumous sagas of brains belonging to Byron, Whitman, Lenin, Einstein, the mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauss, and many others, Burrell describes how the brains of famous men were first collected—by means both fair and foul—and then weighed, measured, dissected, and compared; exhaustive studies analyzed their fissural complexity and cell or neuron size.

In various cities in Europe, Russia, and the United States, brain collections were painstakingly assembled and studied. A veritable who’s who of literary, artistic, musical, scientific, and political achievement waited in Formalin-filled jars for their secrets to be unlocked. The men who built the brain collections were colorful and eccentric figures like Rudolph Wagner, whose study of the brain of Carl Friedrich Gauss led to one of the great scientific debates of the nineteenth century. In America, the Fowler brothers brought phrenology to the United States and made a convert of Walt Whitman, whose brain was donated to science and disappeared under mysterious circumstances.

Eventually, this misconceived phrenological project was abandoned, and with the discovery of new technologies the study of the brain has moved on to a higher plane. But the collections themselves still exist, and today, in Paris, London, Stockholm, Philadelphia, Moscow, and even Tokyo, the brains of nineteenth century geniuses sit idle, gathering dust in their jars. Brian Burrell has visited these collections and looked into the original intentions and purposes of their creators. In the process, he unearths a forgotten byway in the history of science—a tale of colorful eccentrics bent on laying bare the secrets of the human mind.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

BRIAN BURRELL teaches mathematics at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. The author of The Words We Live By and Damn the Torpedoes, he has appeared on C-SPAN's Booknotes with Brian Lamb and the Today show. He makes his home in Northampton, Massachusetts.

From the Inside Flap

The human brain may be the single most complex object in the universe, and one of the most difficult to access. But in the nineteenth century, ever-curious men of science set out to penetrate the dark mysteries of the mind, searching for answers to the question: What makes one man a genius and another a criminal? In short time, their search became a magnificent obsession.

In Postcards from the Brain Museum, author Brian Burrell traces the history of this fascination as he tells the incredible true story of science?s attempt to locate the anatomical signs of brilliance, madness, and cruelty. In elegant prose, Burrell focuses on the posthumous sagas of brains belonging to notorious criminals and to such luminary leaders and thinkers as Albert Einstein, Walt Whitman, and Vladimir Lenin, revealing the peculiar mania of the scientists who dissected the specimens and the sometimes cruel fates of the brains themselves.

As Burrell follows this quixotic trail of geniuses and madmen, traveling around the globe to visit the collections of brains now gathering dust in their jars, he struggles to locate the point at which science begins and obsession leaves off. In the process, he unearths a forgotten byway in the history of science?a mesmerizing tale of colorful eccentrics bent on laying bare the secrets of the human mind. The final result is an enlightening account that is sometimes ghoulish, often bizarre, and thoroughly compelling.

Reviews

Starred Review. When scientists first began probing the human mind, it was commonly believed that the brain itself could provide insight to an individual's mental capacities. Though fields like phrenology—analyzing the brain from the shape of the skull—have been discredited, Burrell (Damn the Torpedoes) reminds us that modern neuroscience shares many of the same preoccupations, including the central notion that the brain contains markers for mental and physical conditions. His history is therefore less a chronicle of quackery than a sympathetic account of scientific innovators whose ideas didn't quite pan out. Anthropologist Cesare Lombroso's theories in the 19th century about the criminal brain, for example, have never been entirely abandoned, and Burrell considers why it was so appealing to many Europeans of the time. Though such proto-neurosurgeons dominate his tale, Burrell also focuses on some of the brilliant minds they studied. We all know Einstein's brain was saved, but how many Americans know that the KGB had a full-time guard on Lenin's dissected organ? Or that Walt Whitman donated his brain to science, only to have a clumsy researcher destroy it? Burrell cites works by Carl Sagan and Stephen Jay Gould that have told parts of this history, and his engaging account earns a place next to these illustrious predecessors on any science reader's bookshelf.

Copyright © Reed Business Information, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Franz Josef Gall's invention of phrenology, in the early eighteen-hundreds, marked the start of the scientific community's lasting obsession with dissecting and measuring the human brain. It seemed reasonable that the brains of exceptional people—whether geniuses or criminals—must share common physical traits that fostered those respective traits, and so scientists obtained and preserved exceptional brains for post-mortem study. The brains of Whitman, Einstein, Lenin, and Charles Guiteau (the assassin of President Garfield) were all recruited for the cause. Several brain collections survive, and Burrell has made a tour of them. He nimbly encompasses science, philosophy, and social history to create an astute and sympathetic history of a scientific cul-de-sac. His dismissal of much contemporary brain science, however—in a chapter called "The New Phrenologists"—smacks of argumentative overreach.

Copyright © 2005 The New Yorker

Taking a page from the Department of Weird Science, Burrell explores collections of the brains of people who were famous for being either geniuses or criminals. Here readers will find out what happened to Lenin's and Einstein's brains; their dispositions culminate Burrell's history of science's attempt to locate anatomical evidence of intellect or evil. Its heyday was from about 1880 to 1910, when scientific societies formed to donate their members' heads to the cause. Burrell explains how, on occasion, technical papers would appear comparing eminent brains, but they were "long on description, short on interpretation, and weakened by a dearth of confirming data." The fad eventually passed, with neuroscience moving to the more productive arenas of cellular anatomy and neurochemistry. The brains still exist, however, and Burrell mordantly embroiders his presentation of a dead-end science with his creepy experiences of observing them, submerged in their formaldehyde-filled jars. While never stooping to mockery, Burrell yet entertains as he conveys a sense of what these nineteenth-century anatomists thought they were accomplishing. Gilbert Taylor

Copyright © American Library Association. All rights reserved

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Chapter 1

The Most Complex Object in the Universe

As neuroscientists never tire of pointing out, the adult human brain is the single most complex object in the universe, and one of the least understood. On average, it weighs about three and a half pounds, most of which is fragile, malleable tissue—so fragile that the brain is the most difficult part of the body to access, remove, handle, and study. A Soviet neuroscientist once likened its consistency to the insides of a watermelon, but even that overstates its structural integrity. If placed on a table, a fresh brain will quickly surrender to gravity and collapse into a heap (more like gelatin than watermelon). Within eight hours, it will begin to decompose, the first part of a dead body to do so. There may indeed be nothing so complex in the universe, nor anything quite as delicate.

The familiar shape of the human brain is somewhat misleading. As a ubiquitous graphic symbol, its most prominent feature, the massive, fissured cerebrum, has come to symbolize the unlimited potential of human thought, if not the very means of man's dominion over the planet. Yet it also bears an unmistakable resemblance to a comical turban, and for most of recorded history it was treated that way.

Until the 1600s, anatomists drew the brain's tortuous surface as a mass of undifferentiated folds, which they likened in their randomness to the folds of the small intestine.1 After puzzling over its purpose, they concluded that the folds were nothing more than an apparatus for the manufacture of phlegm, which the brain squeezed out through the sinuses, and for producing tears, which it squeezed out through the eyes. Only in the last 150 years have scientists come to appreciate what really goes on in those folds, and that their rapid evolution, seemingly accomplished over the last million years, is easily the most impressive achievement in Darwin's universe. In hindsight, the human brain is a triumph of adaptation, so impressive both in size and reputation that until recently it has succeeded in hiding what has in common with the brains of all mammals, which turns out to be quite a bit.

The principal parts of the mammalian brain are the brain stem, the cerebellum, and the forebrain. The stem houses the physical plant. It monitors and regulates unconscious physical processes such as breathing, blood flow, digestion, and glandular secretion. It consists of the medulla, an extension of the spinal cord, a nodule called the pons, and a short connector called the midbrain. The cerebellum, or little brain, lies behind this assembly, and it is aptly named. With its striated exterior and dual hemispheres (at least in primates), it hangs behind the cantilevered back porch of the forebrain like a wasp's nest. Although its role is still not completely understood, the cerebellum is believed to act as a kind of automatic pilot for fine muscle control. If recent studies are correct, it also plays a role in short-term memory, attention, impulse control, emotion, cognition, and future planning. Researchers suspect that it might be a kind of backup unit, an auxiliary brain. Its loss, while far from desirable, is not fatal. The rest of the brain seems to be able to compensate. The forebrain, on the other hand, is indispensable. It is what makes humans human, and, as a result, the search for the anatomical locus of genius, criminality, or insanity begins there.

Neurologists tend to be of two minds about the forebrain. Some see it as two complementary but sometimes competing hemispheres, an uneasy coalition of rationality and impulse. Others attribute the same inner struggle to a cold brain and a hot brain, the entire cerebrum being the source of cool calculation, and a set of nested organs called the limbic system giving rise to hot instincts and urges. The left brain-right brain dichotomy originated in the 1960s when neurosurgeons intervened in acute cases of epilepsy by severing the corpus callosum, the fiber bundle that allows the two hemispheres to communicate with each other. In most cases the seizures went away, leaving patients with a curious split personality. The notion of a hot brain and a cold brain is somewhat older, and reflects a belief that higher functions, specifically the intellect, are situated literally and figuratively above the lower functions. Just as the intellect is supposed to keep the passions in check, the massive cerebrum envelops the limbic organs—the thalamus, hypothalamus, hippocampus, and amygdala—and, on good days, dominates them. Some psychologists like to refer to the embedded limbic system as the reptile brain, a term they invented as a way to market themselves to Madison Avenue and Hollywood. The impulsive animal brain, they say, seeks dominance, safety, or sustenance, and it wants everything NOW—everything from an ice cream sundae to a sport utility vehicle, with little concern for practicality or consequence. Without the intervention of the cold, rational brain, the reptile brain can act quite unreasonably in getting what it craves.

Whether we really are of two minds in a literal sense is far from proven. Yet there is no denying that every mind undergoes a constant struggle between reason and emotion, between impulse and hesitation, between short-term strategies and long-term planning. The conscious brain struggles to rein in the unconscious, to calm nameless fears and anxieties. But if human beings, which is to say the human brain, hot or cold, can be characterized by one driving force, it would have to be curiosity, which has allowed it to explain just about everything in the universe, with two notable exceptions—the universe and itself.

What distinguishes a human brain from an animal brain, from an actual reptile brain? The size of the cerebrum, for one thing, and thus its surface area. But size, it turns out, isn't everything. The brain of an elephant, for example, is about four times as large as a man's, a blue whale's almost six times as large. Neither, of course, can match the forty-to-one body-to-brain-weight ratio in humans, but if ratios were all that mattered, the lowly field mouse, with a body-to-brain ratio of eight-to-one, would sit at the head of the class. Although the thinking part of the cerebrum, its outer shell, is four times thicker in humans than in rats, and four hundred times greater in surface area, the difference between men and mice is several orders of magnitude larger than dimensions alone can explain. It is not so much a matter of size, as of cerebral specialization. As the Alexandrian physician Erasistratus guessed in the fourth century b.c., the advantage lies in the folds, which are more developed in man than in any of the beasts.(2)

Are the folds in the brains of geniuses different from the folds of ordinary folk? The possibility has haunted investigators for a century and a half, and still has its supporters. Although not the only candidate for the anatomical substrate of genius, the folds are easily the front-runner because, contrary to the writings of the ancient anatomists, they are not entirely random. And where there is a pattern, there is assumed to be a meaning. In order to appreciate these patterns, you will not need a medical degree and a copy of Gray's Anatomy. To navigate the brain's tortuous surface, a thumbnail sketch should suffice.

To appreciate the rudimentary topology of the folds of the brain, place your right hand on the table and make a loose fist, relaxing the index finger so that the tip of the thumb rests inside the crux of the first knuckle. In other words, turn your hand into a talking clam, a puppet. Now shut the clam's mouth and imagine the hand enclosed in a mitten. What you are looking at, roughly speaking, is the left cerebral hemisphere of a primate brain. To turn it into a human brain, exchange for the mitten a boxing glove.

The surface of a real brain, of course, is riven by fissures, but these can easily be supplied with a pen. Begin by drawing a heavy line across the knuckles. In a real brain, this line is called the central sulcus (the Latin word for fissure); in older texts it is called the fissure of Rolando, after the eighteenth-century Italian anatomist who first described it. Just in front of this line is the precentral gyrus (gyri, also known as convolutions, are ridges of tissue that lie between fissures); just behind the precentral gyrus lies another ridge called the postcentral gyrus. The first of these contains the motor cortex, which in the left hemisphere controls movement on the right side of the body. The arrangement is inverted—the highest part of the gyrus, nearest the crown of the head, controls the foot, then comes the leg, and so on down to the lowest part of the gyrus, near the temple, which controls the hand and face. The postcentral gyrus registers sensation in a similar mapping. Taken together, these two convolutions, running over the crown of the head, form what is called the sensorimotor cortex.

Another important fissure, the lateral or Sylvian fissure, does not need to be drawn. It coincides with the gap between the thumb and the hand in the boxing glove model, and like that gap, it is very deep. A third useful line of reference, the occipital sulcus, should be added to the picture as a light line running across the very back of the hand, an inch or so above the wrist. Although there are a few other important fissures, these three—the central, Sylvian, and occipital—allow the hemisphere to be divided into its principal parts, the lobes.

The division of the hemispheres into lobes did not come about until the 1850s, and is generally credited to a French anatomist named Louis-Pierre Gratiolet.(3) It may come as a shock to discover that the lobes are not separate and independent units, that Gratiolet divided them somewhat arbitrarily and named them out of convenience by borrowing the words that describe the adjoining bones of the skull. There are four of them—the frontal, parietal, temporal, and occipital bones—delimited by the sutures, the skul...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

FREE shipping within U.S.A.

Destination, rates & speedsSearch results for Postcards from the Brain Museum: The Improbable Search...

Postcards from the Brain Museum: The Improbable Search for Meaning in the Matter of Famous Minds

Seller: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00084410311

Quantity: 2 available

Postcards from the Brain Museum: The Improbable Search for Meaning in the Matter of Famous Minds

Seller: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00082496875

Quantity: 1 available

Postcards from the Brain Museum : The Improbable Search for Meaning in the Matter of Famous Minds

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Seller Inventory # 5012788-6

Quantity: 1 available

Postcards from the Brain Museum : The Improbable Search for Meaning in the Matter of Famous Minds

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 4294249-75

Quantity: 2 available

Postcards from the Brain Museum: The Improbable Search for Meaning in the Matter of Famous Minds

Seller: Greenworld Books, Arlington, TX, U.S.A.

Condition: good. Fast Free Shipping â" Good condition book with a firm cover and clean, readable pages. Shows normal use, including some light wear or limited notes highlighting, yet remains a dependable copy overall. Supplemental items like CDs or access codes may not be included. Seller Inventory # GWV.0385501285.G

Quantity: 1 available

Postcards from the Brain Museum: The Improbable Search for Meaning in the Matter of Famous Minds

Seller: HPB-Ruby, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Seller Inventory # S_430640523

Quantity: 1 available

Postcards from the Brain Museum: The Improbable Search for Meaning in the Matter of Famous Minds

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G0385501285I3N10

Quantity: 1 available

Postcards from the Brain Museum: The Improbable Search for Meaning in the Matter of Famous Minds

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G0385501285I3N10

Quantity: 1 available

Postcards from the Brain Museum: The Improbable Search for Meaning in the Matter of Famous Minds

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G0385501285I4N00

Quantity: 1 available

Postcards from the Brain Museum: The Improbable Search for Meaning in the Matter of Famous Minds

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G0385501285I4N10

Quantity: 1 available