Synopsis

The Lord of the Rings, J.R.R. Tolkien's three-volume epic, is set in the imaginary world of Middle-earth - home to many strange beings, and most notably hobbits, a peace-loving "little people," cheerful and shy. Since its original British publication in 1954-55, the saga has entranced readers of all ages. It is at once a classic myth and a modern fairy tale. Critic Michael Straight has hailed it as one of the "very few works of genius in recent literature." Middle-earth is a world receptive to poets, scholars, children, and all other people of good will. Donald Barr has described it as "a scrubbed morning world, and a ringing nightmare world...especially sunlit, and shadowed by perils very fundamental, of a peculiarly uncompounded darkness." The story of ths world is one of high and heroic adventure. Barr compared it to Beowulf, C.S. Lewis to Orlando Furioso, W.H. Auden to The Thirty-nine Steps. In fact the saga is sui generis - a triumph of imagination which springs to life within its own framework and on its own terms.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

J.R.R. Tolkien (1892–1973) was a distinguished academic, though he is best known for writing The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion, plus other stories and essays. His books have been translated into over sixty languages and have sold many millions of copies worldwide.

From the Back Cover

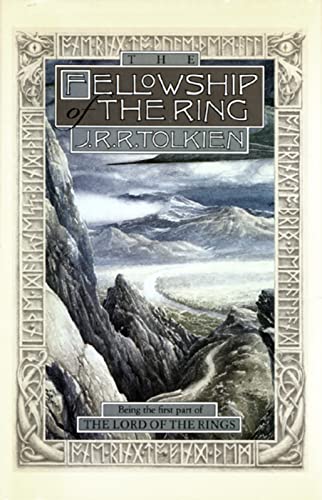

In celebration of The Hobbit's fiftieth anniversary, the authoritative edition of its stirring sequel, The Lord of the Rings, is elegantly presented in handsome, uniform editions. The First Part of The Lord of the Rings finds Bilbo Baggins (hero of The Hobbit) preparing to celebrate his 'eleventy-first' birthday. Sixty unremarkable years have passed since his triumphant return from the orcmines, where he outwitted the horrible Gollum and carried off his magical ring----a feat that cannot go forever unavenged. The ring may hold more power than anyone suspects; indeed, dark forces are already conspiring to snatch it back.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

THE LORD OF THE RINGS

THE FELLOWSHIP OF THE RING

BOOK ONE

Chapter 1

A Long-Expected Party

When Mr. Bilbo Baggins of Bag End announced that he would shortly be

celebrating his eleventy-first birthday with a party of special

magnificence, there was much talk and excitement in Hobbiton.

Bilbo was very rich and very peculiar, and had been the

wonder of the Shire for sixty years, ever since his remarkable

disappearance and unexpected return. The riches he had brought back

from his travels had now become a local legend, and it was popularly

believed, whatever the old folk might say, that the Hill at Bag End

was full of tunnels stuffed with treasure. And if that was not enough

for fame, there was also his prolonged vigour to marvel at. Time wore

on, but it seemed to have little effect on Mr. Baggins. At ninety he

was much the same as at fifty. At ninety-nine they began to call him

well-preserved; but unchanged would have been nearer the mark. There

were some that shook their heads and thought this was too much of a

good thing; it seemed unfair that anyone should possess (apparently)

perpetual youth as well as (reputedly) inexhaustible wealth.

"It will have to be paid for," they said. "It isn"t natural,

and trouble will come of it!"

But so far trouble had not come; and as Mr. Baggins was

generous with his money, most people were willing to forgive him his

oddities and his good fortune. He remained on visiting terms with his

relatives (except, of course, the Sackville-Bagginses), and he had

many devoted admirers among the hobbits of poor and unimportant

families. But he had no close friends, until some of his younger

cousins began to grow up.

The eldest of these, and Bilbo"s favourite, was young Frodo

Baggins. When Bilbo was ninety-nine he adopted Frodo as his heir, and

brought him to live at Bag End; and the hopes of the Sackville-

Bagginses were finally dashed. Bilbo and Frodo happened to have the

same birthday, September 22nd. "You had better come and live here,

Frodo my lad," said Bilbo one day; "and then we can celebrate our

birthday-parties comfortably together." At that time Frodo was still

in his tweens, as the hobbits called the irresponsible twenties

between childhood and coming of age at thirty-three.

Twelve more years passed. Each year the Bagginses had given

very lively combined birthday-parties at Bag End; but now it was

understood that something quite exceptional was being planned for

that autumn. Bilbo was going to be eleventy-one, 111, a rather

curious number, and a very respectable age for a hobbit (the Old Took

himself had only reached 130); and Frodo was going to be thirty-

three, 33, an important number: the date of his "coming of age".

Tongues began to wag in Hobbiton and Bywater; and rumour of

the coming event travelled all over the Shire. The history and

character of Mr. Bilbo Baggins became once again the chief topic of

conversation; and the older folk suddenly found their reminiscences

in welcome demand.

No one had a more attentive audience than old Ham Gamgee,

commonly known as the Gaffer. He held forth at The Ivy Bush, a small

inn on the Bywater road; and he spoke with some authority, for he had

tended the garden at Bag End for forty years, and had helped old

Holman in the same job before that. Now that he was himself growing

old and stiff in the joints, the job was mainly carried on by his

youngest son, Sam Gamgee. Both father and son were on very friendly

terms with Bilbo and Frodo. They lived on the Hill itself, in Number

3 Bagshot Row just below Bag End.

"A very nice well-spoken gentlehobbit is Mr. Bilbo, as I"ve

always said," the Gaffer declared. With perfect truth: for Bilbo was

very polite to him, calling him "Master Hamfast", and consulting him

constantly upon the growing of vegetables — in the matter of "roots",

especially potatoes, the Gaffer was recognized as the leading

authority by all in the neighbourhood (including himself).

"But what about this Frodo that lives with him?" asked Old

Noakes of Bywater. "Baggins is his name, but he"s more than half a

Brandybuck, they say. It beats me why any Baggins of Hobbiton should

go looking for a wife away there in Buckland, where folks are so

queer."

"And no wonder they"re queer," put in Daddy Twofoot (the

Gaffer"s next-door neighbour), "if they live on the wrong side of the

Brandywine River, and right agin the Old Forest. That"s a dark bad

place, if half the tales be true."

"You"re right, Dad!" said the Gaffer. "Not that the

Brandybucks of Buckland live in the Old Forest; but they"re a queer

breed, seemingly. They fool about with boats on that big river — and

that isn"t natural. Small wonder that trouble came of it, I say. But

be that as it may, Mr. Frodo is as nice a young hobbit as you could

wish to meet. Very much like Mr. Bilbo, and in more than looks. After

all his father was a Baggins. A decent respectable hobbit was Mr.

Drogo Baggins; there was never much to tell of him, till he was

drownded."

"Drownded?" said several voices. They had heard this and

other darker rumours before, of course; but hobbits have a passion

for family history, and they were ready to hear it again.

"Well, so they say," said the Gaffer. "You see: Mr. Drogo, he

married poor Miss Primula Brandybuck. She was our Mr. Bilbo"s first

cousin on the mother"s side (her mother being the youngest of the Old

Took"s daughters); and Mr. Drogo was his second cousin. So Mr. Frodo

is his first and second cousin, once removed either way, as the

saying is, if you follow me. And Mr. Drogo was staying at Brandy Hall

with his father-in-law, old Master Gorbadoc, as he often did after

his marriage (him being partial to his vittles, and old Gorbadoc

keeping a mighty generous table); and he went out boating on the

Brandywine River; and he and his wife were drownded, and poor Mr.

Frodo only a child and all."

"I"ve heard they went on the water after dinner in the

moonlight," said Old Noakes; "and it was Drogo"s weight as sunk the

boat."

"And I heard she pushed him in, and he pulled her in after

him," said Sandyman, the Hobbiton miller.

"You shouldn"t listen to all you hear, Sandyman," said the

Gaffer, who did not much like the miller. "There isn"t no call to go

talking of pushing and pulling. Boats are quite tricky enough for

those that sit still without looking further for the cause of

trouble. Anyway: there was this Mr. Frodo left an orphan and

stranded, as you might say, among those queer Bucklanders, being

brought up anyhow in Brandy Hall. A regular warren, by all accounts.

Old Master Gorbadoc never had fewer than a couple of hundred

relations in the place. Mr. Bilbo never did a kinder deed than when

he brought the lad back to live among decent folk.

"But I reckon it was a nasty shock for those Sackville-

Bagginses. They thought they were going to get Bag End, that time

when he went off and was thought to be dead. And then he comes back

and orders them off; and he goes on living and living, and never

looking a day older, bless him! And suddenly he produces an heir, and

has all the papers made out proper. The Sackville-Bagginses won"t

never see the inside of Bag End now, or it is to be hoped not."

"There"s a tidy bit of money tucked away up there, I hear

tell," said a stranger, a visitor on business from Michel Delving in

the Westfarthing. "All the top of your hill is full of tunnels packed

with chests of gold and silver, and jools, by what I"ve heard."

"Then you"ve heard more than I can speak to," answered the

Gaffer. I know nothing about jools. Mr. Bilbo is free with his money,

and there seems no lack of it; but I know of no tunnel-making. I saw

Mr. Bilbo when he came back, a matter of sixty years ago, when I was

a lad. I"d not long come prentice to old Holman (him being my dad"s

cousin), but he had me up at Bag End helping him to keep folks from

trampling and trapessing all over the garden while the sale was on.

And in the middle of it all Mr. Bilbo comes up the Hill with a pony

and some mighty big bags and a couple of chests. I don"t doubt they

were mostly full of treasure he had picked up in foreign parts, where

there be mountains of gold, they say; but there wasn"t enough to fill

tunnels. But my lad Sam will know more about that. He"s in and out of

Bag End. Crazy about stories of the old days he is, and he listens to

all Mr. Bilbo"s tales. Mr. Bilbo has learned him his letters —

meaning no harm, mark you, and I hope no harm will come of it.

"Elves and Dragons! I says to him. "Cabbages and potatoes are

better for me and you. Don"t go getting mixed up in the business of

your betters, or you"ll land in trouble too big for you," I says to

him. And I might say it to others," he added with a look at the

stranger and the miller.

But the Gaffer did not convince his audience. The legend of

Bilbo"s wealth was now too firmly fixed in the minds of the younger

generation of hobbits.

"Ah, but he has likely enough been adding to what he brought

at first," argued the miller, voicing common opinion. "He"s often

away from home. And look at the outlandish folk that visit him:

dwarves coming at night, and that old wandering conjuror, Gandalf,

and all. You can say what you like, Gaffer, but Bag End"s a queer

place, and its folk are queerer."

"And you can say what you like, about what you know no more

of than you do of boating, Mr. Sandyman," retorted the Gaffer,

disliking the miller even more than usual. "If that"s being queer,

then we could do with a bit more queerness in these parts. There"s

some not far away that wouldn"t offer a pint of beer to a friend, if

they lived in a hole with golden walls. But they do things proper at

Bag End. Our Sam says that everyone"s going to be invited to the

party, and there"s going to be presents, mark you, presents for all —

this very month as is."

That very month was September, and as fine as you could ask.

A day or two later a rumour (probably started by the knowledgeable

Sam) was spread about that there were going to be fireworks —

fireworks, what is more, such as had not been seen in the Shire for

nigh on a century, not indeed since the Old Took died.

Days passed and The Day drew nearer. An odd-looking waggon

laden with odd-looking packages rolled into Hobbiton one evening and

toiled up the Hill to Bag End. The startled hobbits peered out of

lamplit doors to gape at it. It was driven by outlandish folk,

singing strange songs: dwarves with long beards and deep hoods. A few

of them remained at Bag End. At the end of the second week in

September a cart came in through Bywater from the direction of the

Brandywine Bridge in broad daylight. An old man was driving it all

alone. He wore a tall pointed blue hat, a long grey cloak, and a

silver scarf. He had a long white beard and bushy eyebrows that stuck

out beyond the brim of his hat. Small hobbit-children ran after the

cart all through Hobbiton and right up the hill. It had a cargo of

fireworks, as they rightly guessed. At Bilbo"s front door the old man

began to unload: there were great bundles of fireworks of all sorts

and shapes, each labelled with a large red G and the elf-rune, .

That was Gandalf"s mark, of course, and the old man was

Gandalf the Wizard, whose fame in the Shire was due mainly to his

skill with fires, smokes, and lights. His real business was far more

difficult and dangerous, but the Shire-folk knew nothing about it. To

them he was just one of the "attractions" at the Party. Hence the

excitement of the hobbit-children. "G for Grand!" they shouted, and

the old man smiled. They knew him by sight, though he only appeared

in Hobbiton occasionally and never stopped long; but neither they nor

any but the oldest of their elders had seen one of his firework

displays — they now belonged to the legendary past.

When the old man, helped by Bilbo and some dwarves, had

finished unloading. Bilbo gave a few pennies away; but not a single

squib or cracker was forthcoming, to the disappointment of the

onlookers.

"Run away now!" said Gandalf. "You will get plenty when the

time comes." Then he disappeared inside with Bilbo, and the door was

shut. The young hobbits stared at the door in vain for a while, and

then made off, feeling that the day of the party would never come.

Inside Bag End, Bilbo and Gandalf were sitting at the open

window of a small room looking out west on to the garden. The late

afternoon was bright and peaceful. The flowers glowed red and golden:

snap-dragons and sun-flowers, and nasturtiums trailing all over the

turf walls and peeping in at the round windows.

"How bright your garden looks!" said Gandalf.

"Yes," said Bilbo. "I am very fond indeed of it, and of all

the dear old Shire; but I think I need a holiday."

"You mean to go on with your plan then?"

"I do. I made up my mind months ago, and I haven"t changed

it."

"Very well. It is no good saying any more. Stick to your

plan — your whole plan, mind — and I hope it will turn out for the

best, for you, and for all of us."

"I hope so. Anyway I mean to enjoy myself on Thursday, and

have my little joke."

"Who will laugh, I wonder?" said Gandalf, shaking his head.

"We shall see," said Bilbo.

The next day more carts rolled up the Hill, and still more

carts. There might have been some grumbling about "dealing locally",

but that very week orders began to pour out of Bag End for every kind

of provision, commodity, or luxury that could be obtained in Hobbiton

or Bywater or anywhere in the neighbourhood. People became

enthusiastic; and they began to tick off the days on the calendar;

and they watched eagerly for the postman, hoping for invitations.

Before long the invitations began pouring out, and the

Hobbiton post-office was blocked, and the Bywater post-office was

snowed under, and voluntary assistant postmen were called for. There

was a constant stream of them going up the Hill, carrying hundreds of

polite variations on Thank you, I shall certainly come.

A notice appeared on the gate at Bag End: NO ADMITTANCE

EXCEPT ON PARTY BUSINESS. Even those who had, or pretended to have

Party Business were seldom allowed inside. Bilbo was busy: writing

invitations, ticking off answers, packing up presents, and making

some private preparations of his own. From the time of Gandalf"s

arrival he remained hidden from view.

One morning the hobbits woke to find the large field, south

of Bilbo"s front door, covered with ropes and poles for tents and

pavilions. A special entrance was cut into the bank leading to the

road, and wide steps and a large white gate were built there. The

three hobbit-families of Bagshot Row, adjoining the field, were

intensely interested and generally envied. Old Gaffer Gamgee stopped

even pretending to work in his garden.

The tents began to go up. There was a specially large

pavilion, so big that the tree that grew in the field was right

inside it, and stood proudly near one end, at the head of the chief

table. Lanterns were hung on all its branches. More promising still

(to the hobbits" mind): an enormous open-air kitchen was erected in

the north corner of the field. A draught of cooks, from every inn and

eating-house for miles around, arrived to supplement the dwarves and

other odd folk that were quartered at Bag End. Excitement rose to its

height.

Then the weather clouded over. That was on Wednesday the eve

of the Party. Anxiety was intense. Then Thursday, September the 22nd,

actually dawned. The sun got up, the clouds vanished, flags were

unfurled and the fun began.

Bilbo Baggins called it a party, but it was really a variety

of entertainments rolled into one. Practically everybody living near

was invited. A very few were overlooked by accident, but as they

turned up all the same, that did not matter. Many people from other

parts of the Shire were also asked; and there were even a few from

outside the borders. Bilbo met the guests (and additions) at the new

white gate in person. He gave away presents to all and sundry — the

latter were those who went out again by a back way and came in again

by the gate. Hobbits give presents to other people on their own

birthdays. Not very expensive ones, as a rule, and not so lavishly as

on this occasion; but it was not a bad system. Actually in Hobbiton

and Bywater every day in the year it was somebody"s birthday, so that

every hobbit in those parts had a fair chance of at least one present

at least once a week. But they never got tired of them.

On this occasion the presents were unusually good. The hobbit-

children were so excited that for a while they almost forgot about

eating. There were toys the like of which they had never seen before,

all beautiful and some obviously magical. Many of them had indeed

been ordered a year before, and had come all the way from the

Mountain and from Dale, and were of real dwarf-make.

When every guest had been welcomed and was finally inside the

gate, there were songs, dances, music, games, and, of course, food

and drink. There were three official meals: lunch, tea, and dinner

(or supper). But lunch and tea were marked chiefly by the fact that

at those times all the guests were sitting down and eating together.

At other times there were merely lots of people eating and drinking —

continuously from elevenses until six-thirty, when the fireworks

started.

The fireworks were by Gandalf: they were not only brought by

him, but designed and made by him; and the special effects, set

pieces, and flights of rockets were let off by him. But there was

also a generous distribution of squibs, crackers, backarappers,

sparklers, torches, dwarf-candles, elf-fountains, goblin-barkers and

thunder-claps. They were all superb. The art of Gandalf improved with

age.

There were rockets like a flight of scintillating birds

singing with sweet voices. There were green trees with trunks of dark

smoke: their leaves opened like a whole spring unfolding in a moment,

and their shining branches dropped glowing flowers down upon the

astonished hobbits, disappearing with a sweet scent just before they

touched their upturned faces. There were fountains of butterflies

that flew glittering into the trees; there were pillars of coloured

fires that rose and turned into eagles, or sailing ships, or a

phalanx of flying swans; there was a red thunderstorm and a shower of

yellow rain; there was a forest of silver spears that sprang suddenly

into the air with a yell like an embattled army, and came down again

into the Water with a hiss like a hundred hot snakes. And there was

also one last surprise, in honour of Bilbo, and it startled the

hobbits exceedingly, as Gandalf intended. The lights went out. A

great smoke went up. It shaped itself like a mountain seen in the

distance, and began to glow at the summit. It spouted green and

scarlet flames. Out flew a red-golden dragon — not life-size, but

terribly life-like: fire came from his jaws, his eyes glared down;

there was a roar, and he whizzed three times over the heads of the

crowd. They all ducked, and many fell flat on their faces. The dragon

passed like an express train, turned a somersault, and burst over

Bywater with a deafening explosion.

"That is the signal for supper!" said Bilbo. The pain and

alarm vanished at once, and the prostrate hobbits leaped to their

feet. There was a splendid supper for everyone; for everyone, that

is, except those invited to the special family dinner-party. This was

held in the great pavilion with the tree. The invitations were

limited to twelve dozen (a number also called by the hobbits one

Gross, though the word was not considered proper to use of people);

and the guests were selected from all the families to which Bilbo and

Frodo were related, with the addition of a few special unrelated

friends (such as Gandalf). Many young hobbits were included, and

present by parental permission; for hobbits were easy-going with

their children in the matter of sitting up late, especially when

there was a chance of getting them a free meal. Bringing up young

hobbits took a lot of provender.

There were many Bagginses and Boffins, and also many Tooks

and Brandybucks; there were various Grubbs (relations of Bilbo

Baggins" grandmother), and various Chubbs (connexions of his Took

grandfather); and a selection of Burrowses, Bolgers, Bracegirdles,

Brockhouses, Goodbodies, Hornblowers and Proudfoots. Some of these

were only very distantly connected with Bilbo, and some of them had

hardly ever been in Hobbiton before, as they lived in remote corners

of the Shire. The Sackville-Bagginses were not forgotten. Otho and

his wife Lobelia were present. They disliked Bilbo and detested

Frodo, but so magnificent was the invitation card, written in golden

ink, that they had felt it was impossible to refuse. Besides, their

cousin, Bilbo, had been specializing in food for many years and his

table had a high reputation.

All the one hundred and forty-four guests expected a pleasant

feast; though they rather dreaded the after-dinner speech of their

host (an inevitable item). He was liable to drag in bits of what he

called poetry; and sometimes, after a glass or two, would allude to

the absurd adventures of his mysterious journey. The guests were not

disappointed: they had a very pleasant feast, in fact an engrossing

entertainment: rich, abundant, varied, and prolonged. The purchase of

provisions fell almost to nothing throughout the district in the

ensuing weeks; but as Bilbo"s catering had depleted the stocks of

most stores, cellars and warehouses for miles around, that did not

matter much.

After the feast (more or less) came the Speech. Most of the

company were, however, now in a tolerant mood, at that delightful

stage which they called "filling up the corners". They were sipping

their favourite drinks, and nibbling at their favourite dainties, and

their fears were forgotten. They were prepared to listen to anything,

and to cheer at every full stop.

My dear People, began Bilbo, rising in his place. "Hear!

Hear! Hear!" they shouted, and kept on repeating it in chorus,

seeming reluctant to follow their own advice. Bilbo left his place

and went and stood on a chair under the illuminated tree. The light

of the lanterns fell on his beaming face; the golden buttons shone on

his embroidered silk waistcoat. They could all see him standing,

waving one hand in the air, the other was in his trouser-pocket.

My dear Bagginses and Boffins, he began again; and my dear

Tooks and Brandybucks, and Grubbs, and Chubbs, and Burrowses, and

Hornblowers, and Bolgers, Bracegirdles, Goodbodies, Brockhouses and

Proudfoots. "ProudFEET!" shouted an elderly hobbit from the back of

the pavilion. His name, of course, was Proudfoot, and well merited;

his feet were large, exceptionally furry, and both were on the table.

Proudfoots, repeated Bilbo. Also my good Sackville-Bagginses

that I welcome back at last to Bag End. Today is my one hundred and

eleventh birthday: I am eleventy-one today! "Hurray! Hurray! Many

Happy Returns!" they shouted, and they hammered joyously on the

tables. Bilbo was doing splendidly. This was the sort of stuff they

liked: short and obvious.

I hope you are all enjoying yourselves as much as I am.

Deafening cheers. Cries of Yes (and No). Noises of trumpets and

horns, pipes and flutes, and other musical instruments. There were,

as has been said, many young hobbits present. Hundreds of musical

crackers had been pulled. Most of them bore the mark DALE on them;

which did not convey much to most of the hobbits, but they all agreed

they were marvellous crackers. They contained instruments, small, but

of perfect make and enchanting tones. Indeed, in one corner some of

the young Tooks and Brandybucks, supposing Uncle Bilbo to have

finished (since he had plainly said all that was necessary), now got

up an impromptu orchestra, and began a merry dance-tune. Master

Everard Took and Miss Melilot Brandybuck got on a table and with

bells in their hands began to dance the Springle-ring: a pretty

dance, but rather vigorous.

But Bilbo had not finished. Seizing a horn from a youngster

near by, he blew three loud hoots. The noise subsided. I shall not

keep you long, he cried. Cheers from all the assembly. I have called

you all together for a Purpose. Something in the way that he said

this made an impression. There was almost silence, and one or two of

the Tooks pricked up their ears.

Indeed, for Three Purposes! First of all, to tell you that I

am immensely fond of you all, and that eleventy-one years is too

short a time to live among such excellent and admirable hobbits.

Tremendous outburst of approval.

I don"t know half of you half as well as I should like; and I

like less than half of you half as well as you deserve. This was

unexpected and rather difficult. There was some scattered clapping,

but most of them were trying to work it out and see if it came to a

compliment.

Secondly, to celebrate my birthday. Cheers again. I should

say: OUR birthday. For it is, of course, also the birthday of my heir

and nephew, Frodo. He comes of age and into his inheritance today.

Some perfunctory clapping by the elders; and some loud shouts

of "Frodo! Frodo! Jolly old Frodo," from the juniors. The Sackville-

Bagginses scowled, and wondered what was meant by "coming into his

inheritance".

Together we score one hundred and forty-four. Your numbers

were chosen to fit this remarkable total: One Gross, if I may use the

expression. No cheers. This was ridiculous. Many of his guests, and

especially the Sackville-Bagginses, were insulted, feeling sure they

had only been asked to fill up the required number, like goods in a

package. "One Gross, indeed! Vulgar expression."

It is also, if I may be allowed to refer to ancient history,

the anniversary of my arrival by barrel at Esgaroth on the Long Lake;

though the fact that it was my birthday slipped my memory on that

occasion. I was only fifty-one then, and birthdays did not seem so

important. The banquet was very splendid, however, though I had a bad

cold at the time, I remember, and could only say "thag you very

buch". I now repeat it more correctly: Thank you very much for coming

to my little party. Obstinate silence. They all feared that a song or

some poetry was now imminent; and they were getting bored. Why

couldn"t he stop talking and let them drink his health? But Bilbo did

not sing or recite. He paused for a moment.

Thirdly and finally, he said, I wish to make an ANNOUNCEMENT.

He spoke this last word so loudly and suddenly that everyone sat up

who still could. I regret to announce that — though, as I said,

eleventy-one years is far too short a time to spend among you — this

is the END. I am going. I am leaving NOW. GOOD-BYE!

He stepped down and vanished. There was a blinding flash of

light, and the guests all blinked. When they opened their eyes Bilbo

was nowhere to be seen. One hundred and forty-four flabbergasted

hobbits sat back speechless. Old Odo Proudfoot removed his feet from

the table and stamped. Then there was a dead silence, until suddenly,

after several deep breaths, every Baggins, Boffin, Took, Brandybuck,

Grubb, Chubb, Burrows, Bolger, Bracegirdle, Brockhouse, Goodbody,

Hornblower, and Proudfoot began to talk at once.

It was generally agreed that the joke was in very bad taste,

and more food and drink were needed to cure the guests of shock and

annoyance. "He"s mad. I always said so," was probably the most

popular comment. Even the Tooks (with a few exceptions) thought

Bilbo"s behaviour was absurd. For the moment most of them took it for

granted that his disappearance was nothing more than a ridiculous

prank.

But old Rory Brandybuck was not so sure. Neither age nor an

enormous dinner had clouded his wits, and he said to his daughter-in-

law, Esmeralda: "There"s something fishy in this, my dear! I believe

that mad Baggins is off again. Silly old fool. But why worry? He

hasn"t taken the vittles with him." He called loudly to Frodo to send

the wine round again.

Frodo was the only one present who had said nothing. For some

time he had sat silent beside Bilbo"s empty chair, and ignored all

remarks and questions. He had enjoyed the joke, of course, even

though he had been in the know. He had difficulty in keeping from

laughter at the indignant surprise of the guests. But at the same

time he felt deeply troubled: he realized suddenly that he loved the

old hobbit dearly. Most of the guests went on eating and drinking and

discussing Bilbo Baggins" oddities, past and present; but the

Sackville-Bagginses had already departed in wrath. Frodo did not want

to have any more to do with the party. He gave orders for more wine

to be served; then he got up and drained his own glass silently to

the health of Bilbo, and slipped out of the pavilion.

As for Bilbo Baggins, even while he was making his speech, he

had been fingering the golden ring in his pocket: his magic ring that

he had kept secret for so many years. As he stepped down he slipped

it on his finger, and he was never seen by any hobbit in Hobbiton

again.

He walked briskly back to his hole, and stood for a moment

listening with a smile to the din in the pavilion and to the sounds

of merrymaking in other parts of the field. Then he went in. He took

off his party clothes, folded up and wrapped in tissue-paper his

embroidered silk waistcoat, and put it away. Then he put on quickly

some old untidy garments, and fastened round his waist a worn leather

belt. On it he hung a short sword in a battered black-leather

scabbard. From a locked drawer, smelling of moth-balls, he took out

an old cloak and hood. They had been locked up as if they were very

precious, but they were so patched and weatherstained that their

original colour could hardly be guessed: it might have been dark

green. They were rather too large for him. He then went into his

study, and from a large strong-box took out a bundle wrapped in old

cloths, and a leather-bound manuscript; and also a large bulky

envelope. The book and bundle he stuffed into the top of a heavy bag

that was standing there, already nearly full. Into the envelope he

slipped his golden ring, and its fine chain, and then sealed it, and

addressed it to Frodo. At first he put it on the mantelpiece, but

suddenly he removed it and stuck it in his pocket. At that moment the

door opened and Gandalf came quickly in.

"Hullo!" said Bilbo. 'I wondered if you would turn up."

'I am glad to find you visible," replied the wizard, sitting

down in a chair. 'I wanted to catch you and have a few final words. I

suppose you feel that everything has gone off splendidly and

according to plan?"

"Yes, I do," said Bilbo. "Though that flash was surprising:

it quite startled me, let alone the others. A little addition of your

own, I suppose?"

"It was. You have wisely kept that ring secret all these

years, and it seemed to me necessary to give your guests something

else that would seem to explain your sudden vanishment."

"And would spoil my joke. You are an interfering old

busybody," laughed Bilbo, "but I expect you know best, as usual."

"I do — when I know anything. But I don"t feel too sure about

this whole affair. It has now come to the final point. You have had

your joke, and alarmed or offended most of your relations, and given

the whole Shire something to talk about for nine days, or ninety-nine

more likely. Are you going any further?"

"Yes, I am. I feel I need a holiday, a very long holiday, as

I have told you before. Probably a permanent holiday: I don"t expect

I shall return. In fact, I don"t mean to, and I have made all

arrangements.

'I am old, Gandalf. I don"t look it, but I am beginning to

feel it in my heart of hearts. Well-preserved indeed!" he

snorted. "Why, I feel all thin, sort of stretched, if you know what I

mean: like butter that has been scraped over too much bread. That

can"t be right. I need a change, or something."

Gandalf looked curiously and closely at him. "No, it does not

seem right," he said thoughtfully. "No, after all I believe your plan

is probably the best."

"Well, I"ve made up my mind, anyway. I want to see mountains

again, Gandalf — mountains; and then find somewhere where I can rest.

In peace and quiet, without a lot of relatives prying around, and a

string of confounded visitors hanging on the bell. I might find

somewhere where I can finish my book. I have thought of a nice ending

for it: and he lived happily ever after to the end of his days."

Gandalf laughed. "I hope he will. But nobody will read the

book, however it ends."

"Oh, they may, in years to come. Frodo has read some already,

as far as it has gone. You"ll keep an eye on Frodo, won"t you?"

"Yes, I will — two eyes, as often as I can spare them."

"He would come with me, of course, if I asked him. In fact he

offered to once, just before the party. But he does not really want

to, yet. I want to see the wild country again before I die, and the

Mountains; but he is still in love with the Shire, with woods and

fields and little rivers. He ought to be comfortable here. I am

leaving everything to him, of course, except a few oddments. I hope

he will be happy, when he gets used to being on his own. It"s time he

was his own master now."

"Everything?" said Gandalf. "The ring as well? You agreed to

that, you remember."

"Well, er, yes, I suppose so," stammered Bilbo.

"Where is it?"

"In an envelope, if you must know," said Bilbo

impatiently. "There on the mantelpiece. Well, no! Here it is in my

pocket!" He hesitated. "Isn"t that odd now?" he said softly to

himself. "Yet after all, why not? Why shouldn"t it stay there?"

Gandalf looked again very hard at Bilbo, and there was a

gleam in his eyes. "I think, Bilbo," he said quietly, "I should leave

it behind. Don"t you want to?"

"Well yes — and no. Now it comes to it, I don"t like parting

with it at all, I may say. And I don"t really see why I should. Why

do you want me to?" he asked, and a curious change came over his

voice. It was sharp with suspicion and annoyance. "You are always

badgering me about my ring; but you have never bothered me about the

other things that I got on my journey."

"No, but I had to badger you," said Gandalf. "I wanted the

truth. It was important. Magic rings are — well, magical; and they

are rare and curious. I was professionally interested in your ring,

you may say; and I still am. I should like to know where it is, if

you go wandering again. Also I think you have had it quite long

enough. You won"t need it any more, Bilbo, unless I am quite

mistaken."

Bilbo flushed, and there was an angry light in his eyes. His

kindly face grew hard. "Why not?" he cried. "And what business is it

of yours, anyway, to know what I do with my own things? It is my own.

I found it. It came to me."

"Yes, yes," said Gandalf. "But there is no need to get angry."

"If I am it is your fault," said Bilbo. "It is mine, I tell

you. My own. My precious. Yes, my precious."

The wizard"s face remained grave and attentive, and only a

flicker in his deep eyes showed that he was startled and indeed

alarmed. "It has been called that before," he said, "but not by you."

"But I say it now. And why not? Even if Gollum said the same

once. It"s not his now, but mine. And I shall keep it, I say."

Gandalf stood up. He spoke sternly. "You will be a fool if

you do, Bilbo," he said. "You make that clearer with every word you

say. It has got far too much hold on you. Let it go! And then you can

go yourself, and be free."

"I"ll do as I choose and go as I please," said Bilbo

obstinately.

"Now, now, my dear hobbit!" said Gandalf. "All your long life

we have been friends, and you owe me something. Come! Do as you

promised: give it up!"

"Well, if you want my ring yourself, say so!" cried

Bilbo. "But you won"t get it. I won"t give my precious away, I tell

you." His hand strayed to the hilt of his small sword.

Gandalf"s eyes flashed. "It will be my turn to get angry

soon," he said. "If you say that again, I shall. Then you will see

Gandalf the Grey uncloaked." He took a step towards the hobbit, and

he seemed to grow tall and menacing; his shadow filled the little

room.

Bilbo backed away to the wall, breathing hard, his hand

clutching at his pocket. They stood for a while facing one another,

and the air of the room tingled. Gandalf"s eyes remained bent on the

hobbit. Slowly his hands relaxed, and he began to tremble.

"I don"t know what has come over you, Gandalf," he said. "You

have never been like this before. What is it all about? It is mine

isn"t it? I found it, and Gollum would have killed me, if I hadn"t

kept it. I"m not a thief, whatever he said."

"I have never called you one," Gandalf answered. "And I am

not one either. I am not trying to rob you, but to help you. I wish

you would trust me, as you used." He turned away, and the shadow

passed. He seemed to dwindle again to an old grey man, bent and

troubled.

Bilbo drew his hand over his eyes. "I am sorry," he

said. "But I felt so queer. And yet it would be a relief in a way not

to be bothered with it any more. It has been so growing on my mind

lately. Sometimes I have felt it was like an eye looking at me. And I

am always wanting to put it on and disappear, don"t you know; or

wondering if it is safe, and pulling it out to make sure. I tried

locking it up, but I found I couldn"t rest without it in my pocket. I

don"t know why. And I don"t seem able to make up my mind."

"Then trust mine," said Gandalf. "It is quite made up. Go

away and leave it behind. Stop possessing it. Give it to Frodo, and I

will look after him."

Bilbo stood for a moment tense and undecided. Presently he

sighed. "All right," he said with an effort. "I will." Then he

shrugged his shoulders, and smiled rather ruefully. "After all that"s

what this party business was all about, really: to give away lots of

birthday presents, and somehow make it easier to give it away at the

same time. It hasn"t made it any easier in the end, but it would be a

pity to waste all my preparations. It would quite spoil the joke."

"Indeed it would take away the only point I ever saw in the

affair," said Gandalf.

"Very well," said Bilbo, "it goes to Frodo with all the

rest." He drew a deep breath. "And now I really must be starting, or

somebody else will catch me. I have said good-bye, and I couldn"t

bear to do it all over again." He picked up his bag and moved to the

door.

"You have still got the ring in your pocket," said the wizard.

"Well, so I have!" cried Bilbo. "And my will and all the

other documents too. You had better take it and deliver it for me.

That will be safest."

"No, don"t give the ring to me," said Gandalf. "Put it on the

mantelpiece. It will be safe enough there, till Frodo comes. I shall

wait for him."

Bilbo took out the envelope, but just as he was about to set

it by the clock, his hand jerked back, and the packet fell on the

floor. Before he could pick it up, the wizard stooped and seized it

and set it in its place. A spasm of anger passed swiftly over the

hobbit"s face again. Suddenly it gave way to a look of relief and a

laugh.

"Well, that"s that," he said. "Now I"m off!"

They went out into the hall. Bilbo chose his favourite stick

from the stand; then he whistled. Three dwarves came out of different

rooms where they had been busy.

"Is everything ready?" asked Bilbo. "Everything packed and

labelled?"

"Everything," they answered.

"Well, let"s start then!" He stepped out of the front-door.

It was a fine night, and the black sky was dotted with stars.

He looked up, sniffing the air. "What fun! What fun to be off again,

off on the Road with dwarves! This is what I have really been longing

for, for years! Good-bye!" he said, looking at his old home and

bowing to the door. "Good-bye, Gandalf!"

"Good-bye, for the present, Bilbo. Take care of yourself! You

are old enough, and perhaps wise enough."

"Take care! I don"t care. Don"t you worry about me! I am as

happy now as I have ever been, and that is saying a great deal. But

the time has come. I am being swept off my feet at last," he added,

and then in a low voice, as if to himself, he sang softly in the dark:

The Road goes ever on and on

Down from the door where it began.

Now far ahead the Road has gone,

And I must follow, if I can,

Pursuing it with eager feet,

Until it joins some larger way

Where many paths and errands meet.

And whither then? I cannot say.

He paused, silent for a moment. Then without another word he

turned away from the lights and voices in the fields and tents, and

followed by his three companions went round into his garden, and

trotted down the long sloping path. He jumped over a low place in the

hedge at the bottom, and took to the meadows, passing into the night

like a rustle of wind in the grass.

Gandalf remained for a while staring after him into the

darkness. "Goodbye, my dear Bilbo — until our next meeting!" he said

softly and went back indoors.

Frodo came in soon afterwards, and found him sitting in the

dark, deep in thought. "Has he gone?" he asked.

"Yes," answered Gandalf, "he has gone at last."

"I wish — I mean, I hoped until this evening that it was only

a joke," said Frodo. "But I knew in my heart that he really meant to

go. He always used to joke about serious things. I wish I had come

back sooner, just to see him off."

"I think really he preferred slipping off quietly in the

end," said Gandalf. "Don"t be too troubled. He"ll be all right — now.

He left a packet for you. There it is!"

Frodo took the envelope from the mantelpiece, and glanced at

it, but did not open it.

"You"ll find his will and all the other documents in there, I

think," said the wizard. "You are the master of Bag End now. And

also, I fancy, you"ll find a golden ring."

"The ring!" exclaimed Frodo. "Has he left me that? I wonder

why. Still, it may be useful."

"It may, and it may not," said Gandalf. "I should not make

use of it, if I were you. But keep it secret, and keep it safe! Now I

am going to bed."

As master of Bag End Frodo felt it his painful duty to say

good-bye to the guests. Rumours of strange events had by now spread

all over the field, but Frodo would only say no doubt everything will

be cleared up in the morning. About midnight carriages came for the

important folk. One by one they rolled away, filled with full but

very unsatisfied hobbits. Gardeners came by arrangement, and removed

in wheel-barrows those that had inadvertently remained behind.

Night slowly passed. The sun rose. The hobbits rose rather

later. Morning went on. People came and began (by orders) to clear

away the pavilions and the tables and the chairs, and the spoons and

knives and bottles and plates, and the lanterns, and the flowering

shrubs in boxes, and the crumbs and cracker-paper, the forgotten bags

and gloves and handkerchiefs, and the uneaten food (a very small

item). Then a number of other people came (without orders):

Bagginses, and Boffins, and Bolgers, and Tooks, and other guests that

lived or were staying near. By mid-day, when even the best-fed were

out and about again, there was a large crowd at Bag End, uninvited

but not unexpected.

Frodo was waiting on the step, smiling, but looking rather

tired and worried. He welcomed all the callers, but he had not much

more to say than before. His reply to all inquiries was simply

this: "Mr. Bilbo Baggins has gone away; as far as I know, for good."

Some of the visitors he invited to come inside, as Bilbo had

left "messages" for them.

Inside in the hall there was piled a large assortment of

packages and parcels and small articles of furniture. On every item

there was a label tied. There were several labels of this sort:

For ADELARD TOOK, for his VERY OWN, from Bilbo; on an

umbrella. Adelard had carried off many unlabelled ones.

For DORA BAGGINS in memory of a LONG correspondence, with

love from Bilbo; on a large waste-paper basket. Dora was Drogo"s

sister and the eldest surviving female relative of Bilbo and Frodo;

she was ninety-nine, and had written reams of good advice for more

than half a century.

For MILO BURROWS, hoping it will be useful, from B.B; on a

gold pen and ink-bottle. Milo never answered letters.

For ANGELICA"S use, from Uncle Bilbo; on a round convex

mirror. She was a young Baggins, and too obviously considered her

face shapely.

For the collection of HUGO BRACEGIRDLE, from a contributor;

on an (empty) book-case. Hugo was a great borrower of books, and

worse than usual at returning them.

For LOBELIA SACKVILLE-BAGGINS, as a PRESENT; on a case of

silver spoons. Bilbo believed that she had acquired a good many of

his spoons, while he was away on his former journey. Lobelia knew

that quite well. When she arrived later in the day, she took the

point at once, but she also took the spoons.

This is only a small selection of the assembled presents.

Bilbo"s residence had got rather cluttered up with things in the

course of his long life. It was a tendency of hobbit-holes to get

cluttered up: for which the custom of giving so many birthday-

presents was largely responsible. Not, of course, that the birthday-

presents were always new; there were one or two old mathoms of

forgotten uses that had circulated all around the district; but Bilbo

had usually given new presents, and kept those that he received. The

old hole was now being cleared a little.

Every one of the various parting gifts had labels, written

out personally by Bilbo, and several had some point, or some joke.

But, of course, most of the things were given where they would be

wanted and welcome. The poorer hobbits, and especially those of

Bagshot Row, did very well. Old Gaffer Gamgee got two sacks of

potatoes, a new spade, a woollen waistcoat, and a bottle of ointment

for creaking joints. Old Rory Brandybuck, in return for much

hospitality, got a dozen bottles of Old Winyards: a strong red wine

from the Southfarthing, and now quite mature, as it had been laid

down by Bilbo"s father. Rory quite forgave Bilbo, and voted him a

capital fellow after the first bottle.

There was plenty of everything left for Frodo. And, of

course, all the chief treasures, as well as the books, pictures, and

more than enough furniture, were left in his possession. There was,

however, no sign nor mention of money or jewellery: not a penny-piece

or a glass bead was given away.

Frodo had a very trying time that afternoon. A false rumour

that the whole household was being distributed free spread like

wildfire; and before long the place was packed with people who had no

business there, but could not be kept out. Labels got torn off and

mixed, and quarrels broke out. Some people tried to do swaps and

deals in the hall; and others tried to make off with minor items not

addressed to them, or with anything that seemed unwanted or

unwatched. The road to the gate was blocked with barrows and

handcarts.

In the middle of the commotion the Sackville-Bagginses

arrived. Frodo had retired for a while and left his friend Merry

Brandybuck to keep an eye on things. When Otho loudly demanded to see

Frodo, Merry bowed politely.

"He is indisposed," he said. "He is resting."

"Hiding, you mean," said Lobelia. "Anyway we want to see him

and we mean to see him. Just go and tell him so!"

Merry left them a long while in the hall, and they had time

to discover their parting gift of spoons. It did not improve their

tempers. Eventually they were shown into the study. Frodo was sitting

at a table with a lot of papers in front of him. He looked

indisposed — to see Sackville-Bagginses at any rate; and he stood up,

fidgeting with something in his pocket. But he spoke quite politely.

The Sackville-Bagginses were rather offensive. They began by

offering him bad bargain-prices (as between friends) for various

valuable and unlabelled things. When Frodo replied that only the

things specially directed by Bilbo were being given away, they said

the whole affair was very fishy.

"Only one thing is clear to me," said Otho, "and that is that

you are doing exceedingly well out of it. I insist on seeing the

will."

Otho would have been Bilbo"s heir, but for the adoption of

Frodo. He read the will carefully and snorted. It was, unfortunately,

very clear and correct (according to the legal customs of hobbits,

which demand among other things seven signatures of witnesses in red

ink).

"Foiled again!" he said to his wife. "And after waiting sixty

years. Spoons? Fiddlesticks!" He snapped his fingers under Frodo"s

nose and stumped off. But Lobelia was not so easily got rid of. A

little later Frodo came out of the study to see how things were going

on and found her still about the place, investigating nooks and

corners and tapping the floors. He escorted her firmly off the

premises, after he had relieved her of several small (but rather

valuable) articles that had somehow fallen inside her umbrella. Her

face looked as if she was in the throes of thinking out a really

crushing parting remark; but all she found to say, turning round on

the step, was:

"You"ll live to regret it, young fellow! Why didn"t you go

too? You don"t belong here; you"re no Baggins — you — you"re a

Brandybuck!"

"Did you hear that, Merry? That was an insult, if you like,"

said Frodo as he shut the door on her.

"It was a compliment," said Merry Brandybuck, "and so, of

course, not true."

Then they went round the hole, and evicted three young

hobbits (two Boffins and a Bolger) who were knocking holes in the

walls of one of the cellars. Frodo also had a tussle with young

Sancho Proudfoot (old Odo Proudfoot"s grandson), who had begun an

excavation in the larger pantry, where he thought there was an echo.

The legend of Bilbo"s gold excited both curiosity and hope; for

legendary gold (mysteriously obtained, if not positively ill-gotten)

is, as every one knows, any one"s for the finding — unless the search

is interrupted.

When he had overcome Sancho and pushed him out, Frodo

collapsed on a chair in the hall. "It"s time to close the shop,

Merry," he said. "Lock the door, and don"t open it to anyone today,

not even if they bring a battering ram." Then he went to revive

himself with a belated cup of tea.

He had hardly sat down, when there came a soft knock at the

front-door. "Lobelia again most likely," he thought. "She must have

thought of something really nasty, and have come back again to say

it. It can wait."

He went on with his tea. The knock was repeated, much louder,

but he took no notice. Suddenly the wizard"s head appeared at the

window.

"If you don"t let me in, Frodo, I shall blow your door right

down your hole and out through the hill," he said.

"My dear Gandalf! Half a minute!" cried Frodo, running out of

the room to the door. "Come in! Come in! I thought it was Lobelia."

"Then I forgive you. But I saw her some time ago, driving a

pony-trap towards Bywater with a face that would have curdled new

milk."

"She had already nearly curdled me. Honestly, I nearly tried

on Bilbo"s ring. I longed to disappear."

"Don"t do that!" said Gandalf, sitting down. "Do be careful

of that ring, Frodo! In fact, it is partly about that that I have

come to say a last word."

"Well, what about it?"

"What do you know already?"

"Only what Bilbo told me. I have heard his story: how he

found it, and how he used it: on his journey, I mean."

"Which story, I wonder," said Gandalf.

"Oh, not what he told the dwarves and put in his book," said

Frodo. "He told me the true story soon after I came to live here. He

said you had pestered him till he told you, so I had better know

too. "No secrets between us, Frodo," he said; "but they are not to go

any further. It"s mine anyway.""

"That"s interesting," said Gandalf. "Well, what did you think

of it all?"

"If you mean, inventing all that about a "present", well, I

thought the true story much more likely, and I couldn"t see the point

of altering it at all. It was very unlike Bilbo to do so, anyway; and

I thought it rather odd."

"So did I. But odd things may happen to people that have such

treasures — if they use them. Let it be a warning to you to be very

careful with it. It may have other powers than just making you vanish

when you wish to."

"I don"t understand," said Frodo.

"Neither do I," answered the wizard. "I have merely begun to

wonder about the ring, especially since last night. No need to worry.

But if you take my advice you will use it very seldom, or not at all.

At least I beg you not to use it in any way that will cause talk or

rouse suspicion. I say again: keep it safe, and keep it secret!"

"You are very mysterious! What are you afraid of?"

"I am not certain, so I will say no more. I may be able to

tell you something when I come back. I am going off at once: so this

is good-bye for the present." He got up.

"At once!" cried Frodo. "Why, I thought you were staying on

for at least a week. I was looking forward to your help."

"I did mean to — but I have had to change my mind. I may be

away for a good while; but I"ll come and see you again, as soon as I

can. Expect me when you see me! I shall slip in quietly. I shan"t

often be visiting the Shire openly again. I find that I have become

rather unpopular. They say I am a nuisance and a disturber of the

peace. Some people are actually accusing me of spiriting Bilbo away,

or worse. If you want to know, there is supposed to be a plot between

you and me to get hold of his wealth."

"Some people!" exclaimed Frodo. "You mean Otho and Lobelia.

How abominable! I would give them Bag End and everything else, if I

could get Bilbo back and go off tramping in the country with him. I

love the Shire. But I begin to wish, somehow, that I had gone too. I

wonder if I shall ever see him again."

"So do I," said Gandalf. "And I wonder many other things.

Good-bye now! Take care of yourself! Look out for me, especially at

unlikely times! Good-bye!"

Frodo saw him to the door. He gave a final wave of his hand,

and walked off at a surprising pace; but Frodo thought the old wizard

looked unusually bent, almost as if he was carrying a great weight.

The evening was closing in, and his cloaked figure quickly vanished

into the twilight. Frodo did not see him again for a long time.

Copyright © 1954, 1965, 1966 by J.R.R. Tolkien;

1954 edition copyright © renewed 1982 by Christopher R. Tolkien,

Michael H.R. Tolkien, John F.R. Tolkien and Priscilla M.A.R. Tolkien;

1965/1966 editions copyright © renewed 1993, 1994 by Christopher R.

Tolkien, John F.R. Tolkien and Priscilla M.A.R. Tolkien.

All rights reserved.

Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Company.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

Other Popular Editions of the Same Title

Search results for The Fellowship Of The Ring: Being the First Part of...

The Fellowship Of The Ring: Being the First Part of The Lord of the Rings (The Lord of the Rings, 1)

Seller: Evergreen Goodwill, Seattle, WA, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Acceptable. Seller Inventory # mon0000225473

The Fellowship Of The Ring: Being the First Part of The Lord of the Rings

Seller: Goodwill Books, Hillsboro, OR, U.S.A.

Condition: good. Signs of wear and consistent use. Seller Inventory # GICWV.0395489318.G

The Fellowship Of The Ring: Being the First Part of The Lord of the Rings

Seller: Roundabout Books, Greenfield, MA, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Good. Condition Notes: Moderate edge wear. Binding good. May have marking in text. We sometimes source from libraries. We ship in recyclable American-made mailers. 100% money-back guarantee on all orders. Seller Inventory # 1727868

The Fellowship of the Ring: Being the First Part of The Lord of the Rings (1)

Seller: The Maryland Book Bank, Baltimore, MD, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Very Good. 2nd ed. Used - Very Good. Seller Inventory # 4-C-3-1001

The Fellowship Of The Ring: Being the First Part of The Lord of the Rings (The Lord of the Rings, 1) [Hardcover] Tolkien, J.R.R.

Seller: RUSH HOUR BUSINESS, Worcester, MA, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Pages are clean with no markings. Seller Inventory # KWAMBIRA-0002-06-17-2025

Fellowship of the Ring

Seller: GreatBookPrices, Columbia, MD, U.S.A.

Condition: New. Seller Inventory # 459034-n

The Fellowship of the Ring: Being the First Part of The Lord of the Rings (1)

Seller: Lakeside Books, Benton Harbor, MI, U.S.A.

Condition: New. Brand New! Not Overstocks or Low Quality Book Club Editions! Direct From the Publisher! We're not a giant, faceless warehouse organization! We're a small town bookstore that loves books and loves it's customers! Buy from Lakeside Books! Seller Inventory # OTF-S-9780395489314

Fellowship of the Ring

Seller: GreatBookPrices, Columbia, MD, U.S.A.

Condition: As New. Unread book in perfect condition. Seller Inventory # 459034

The Fellowship of the Ring Format: Hardcover

Seller: INDOO, Avenel, NJ, U.S.A.

Condition: As New. Unread copy in mint condition. Seller Inventory # TN9780395489314

The Fellowship of the Ring Format: Hardcover

Seller: INDOO, Avenel, NJ, U.S.A.

Condition: New. Brand New. Seller Inventory # 9780395489314