Items related to Messenger: The Legacy of Mattie J.T. Stepanek and Heartsongs

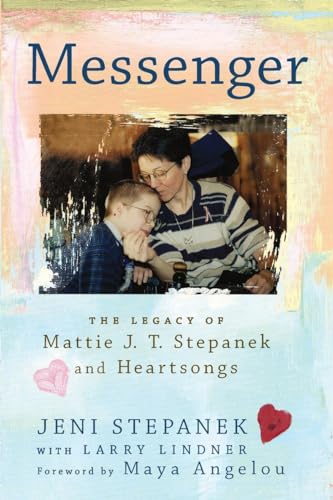

Mattie Stepanek's Heartsongs books were a phenomenon. Not only did they hit the bestseller lists, but the books-and Mattie himself- were a source of inspiration to many, and brought him major recognition. Jimmy Carter described young Mattie Stepanek as "the most remarkable person I have ever known."

In Messenger, Jeni Stepanek shares the inspiring story of her son's life. Mattie was born with a rare disorder called Dysautonomic Mitochondrial Myopathy, and Jeni was advised to institutionalize him. Instead, she nurtured a child who transformed his hardships into a worldwide message of peace and hope. Though Mattie suffered through his disease, his mother's disabilities, and the loss of his three older siblings, he never abandoned his positive spirit. His Heartsong- the word he used to describe a person's inner self-spread a philosophy that peace begins with an attitude and can spread to the entire world.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Sunrise on the Pier

. . . The sky grows

Shadows, rising

With the passing of time. . . .

The sky sighs,

Ebbing with tides

Of pre-dawn nothingness,

And yet,

Seas of everything created,

Tucked into waves. . . .

The sun rises

Caressing spirits

With the passing of time

And the promise of hope

And the belief of life

That gets better with age

As we edge into

The day that once was

Our distant tomorrow.

— From “Night Light” in Reflections of a Peacemaker: A Portrait Through Heartsongs, page 29.

Nell was getting more and more soaked each time the water sprinkler circled back around. She had fallen off the boardwalk into the beach grass on her way back from the ice cream shop and was now unable to get up, afraid she might have broken her leg. She also had a painful abrasion on her forehead.

Still, she was laughing to herself. While she waited for help getting to the emergency room, the sprinkler system came on automatically, and she knew the sight of her sitting there dripping wet was ridiculous— even more so because Mema, who had gone with her for ice cream, kept running off each time the ch ch ch ch ch of the sprinkler circled around. Mema had wanted to stay right by Nell’s side while others in the group went for help but had her hair done that day and didn’t want it ruined. So she would jump back with each spray, apologizing from a distance about her visit to the beauty parlor. This made Nell laugh even harder.

We were toward the end of our annual week at the beach on North Carolina’s Outer Banks. Mattie and I had been coming every year since 1992, when he was two, courtesy of my dear friend Sandy Newcomb and her parents, Mema and Papa (whose real names are Sue and Henry Newcomb). They always stayed in a two-story condo right by the water— a crazy flophouse with red and purple walls and more air mattresses and foldout sofas than bedrooms—and they had us down for a week or more every July.

The summer of 2000 had been better than ever in the sense that all our kin were able to make it for at least a couple of days. By “kin,” Mattie and I meant the family with whom you didn’t necessarily share blood but with whom you’re related through life. These relationships were always wonderful to him, whereas blood relations could be sweet or sour.

Our “immediate kin” consisted of Sandy, who by that point had become more like a sister to me and like a favorite aunt to Mattie; Sandy’s daughters, Heather and Jamie Dobbins, and her son, Chris Dobbins (all were teenagers or young adults then); and Mema and Papa. We playfully called this group the “Step’obbi’comb Fam”—combining Stepanek, Dobbins, and Newcomb into one “kinship unit.”

Some “extended kin” were also a part of this beach vacation, including Mattie’s best friend, Hope Wyatt; Hope’s mother, Susan (Susan’s husband, Ron, on a peacekeeping mission in Kosovo at the time, was the one who brought Mattie the United Nations flag); and Nell Paul and her husband Larry. Sandy had met Nell in a La Leche class when they were both expecting their first children, and through her I had become good friends with Nell, too. Mattie called us the Three Granny’olas.

It turned out Nell hadn’t broken her leg after all. And although the gash on her forehead was a nasty one, it wasn’t anything time and some pain medication wouldn’t heal.

Nell had been a source of humor all week. The night we arrived, she explained that she was having health problems that made it difficult for her to stand on her feet too long. But she offered to help Sandy make a chicken tetrazzini dinner that night by calling out, without a hint of irony, that at least while sitting at the table, she could very easily “cut the cheese.” When we all burst out laughing, she responded with some amount of confusion and indignity that “not being able to walk around a lot has nothing to do with my ability to cut the cheese”—which only made us roar.

Nell grew up a preacher’s daughter in the South in the 1940s and 50s and simply didn’t know certain idioms and other common wordplays. We had such fun teasing her all week about the T-shirts you see at the beach with suggestive double entendres and such. We entitled that vacation “The Education of Nell,” playing practical jokes on her as we went. One day I looked sidelong at Mattie with a mischievous gleam and said to her, “I suppose you’ve never heard the phrase ‘duck on the head.’” Mattie went along and called out, “Mom, I can’t believe you’d even tell her that. That’s, like, rude.” I then said to Nell with feigned indignation, “Never mind, we aren’t going to go there.”

Later in the week, Mattie and Hope staged a tattling scene wherein Hope accused Mattie of saying “duck on the head,” and Mattie “defended himself” by responding that he was only telling Hope why she shouldn’t say it, and I “scolded” both of them. Nell felt terrible. She had been repeating the phrase here and there in the belief we had been pulling her leg and thought it was she who got the kids going. We didn’t disavow her of this notion. Then, on one of our last days there, we all tied tiny stuffed ducks to our heads and went around the side of the pool where Nell was sitting, quacking at her.

Mattie was having the time of his life. Chris would throw him into the deep end of the pool, and he’d soon be bobbing to the surface, yelling to be thrown in again. He also began interviewing all the kin for a fun book he and I were envisioning, The Unsavable Graces. He wrote goofy poems and went to the top of a giant sand dune called Jockey’s Ridge. He went with me to Mass recited in Spanish, which we did every summer; doing so allowed us to really think about the essence of God in rituals rather than just recite prayers from rote. He and Hope, both blond, ambushed Chris, also blond, while Chris was trying to flirt with a pretty girl in an orange-pink bikini, saying, “Daddy, we’re hungry, and Mommy said it’s your turn to fix us lunch.” Chris later married that girl, Cynthia, and Mat-tie was best man at their wedding.

Mattie’s disability had progressed since the previous summer, but we were used to that and always found ways to accommodate his condition without letting it ratchet down the fun. For instance, when Mattie was six and seven, he could walk to the pool, do backward flips into the water, swim laps, and dive down ten feet to the bottom to grab pennies. As long as he remained attached to a tank of oxygen, he would be fine. We would rig a twenty-five-foot tube that connected the nasal cannula in his nostrils to the tank so he could swim anywhere in the pool and never be without the supplemental oxygen. When he wasn’t in the water, he would drag the tank behind him on a cart, sometimes using his cannula and tubing as a jump rope and letting other kids take turns as he swung it.

When Mattie was eight, he needed a wheelchair with the oxygen on the back of it to get to the pool but could still move around pretty well once he was in the water. The summer he turned nine, he went from one oxygen tank to two, but as long as he had the extra oxygen, he didn’t have the frequent feeling that he was suffocating.

This time around, Mattie was too weak to swim much—he would come up gasping—but he could still enjoy Chris throwing him into the deep end. To compensate, we bought a ten-foot blow-up alligator fl oat that Mattie could hang on to in the water. The object was always to continue the fun no matter the challenge. There was always another solution, another fix.

Granted, this year there had been changes that were more marked than in previous summers. At night, Mattie now had to be on a BiPAP machine, short for bi-level positive airway pressure. It involves wearing a mask over your nose or mouth or, in Mattie’s case, both, that helps you breathe easier when you’re short of breath. Mattie also had to wear it during the day if he felt exhausted, such as right after pool time. This was in addition to the pulse oximetry and cardiorespiratory monitors to which he was connected anytime he was sitting or lying at rest since the day he was born, which would let us know if his heart or lungs weren’t doing what they were supposed to. The dysautonomic in dysautonomic mitochondrial myopathy means things in the body that should happen automatically don’t always. For example, when someone switches from physical activity to sitting, the heart self-regulates by beating more slowly. But Mattie’s heart could overshoot the mark and start to “forget” to keep beating while he was at rest rather than simply slow a bit; the fine-tuning just wasn’t there. If his heart rate fell too low, the machine triggered an alarm that would signal someone to jiggle him or provide other tactile stimulation or remind him to breathe more deeply for a minute until his heart could receive the “signal” and get its pumping back in sync with his body’s needs.

Understanding this condition and how to deal with it came slowly, across the lifespans of all four of my children. The medical community didn’t even have a name for it until my two eldest had died. It was simply called dysautonomia of unknown cause, and early on I was told that subsequent children would not be affected. Not until Mattie was two years old and my third child was months from death did doctors understand that it was a condition of faulty mitochondria—an essential component of every cell in a person’s body.

I was actually diagnosed first—with the adult-onset form—then the children. Two years later, after my third child died and Mattie was only four, I was in a wheelchair. Now we were all too familiar with the condition’s devastating effects.

We were used to adding supports and medical machinery to compensate for the detrimental effects of this progressive condition, and then we would keep going. But that summer, the changes weren’t just in the BiPAP machinery or even in the fact that Mattie didn’t have the energy to really swim. Hope, who was two years his junior, was now several inches taller than he was. Mattie’s shoe size, in fact, was the same as in kindergarten—a child’s 11. Growth taxed Mattie’s autonomic system, and somehow his body knew that. In addition, he could not walk across the beach to the ocean. Mattie didn’t need his wheelchair because he was incapable of walking; he needed it in large part because he would tire so easily.

In previous years, he had the energy to walk across the sand to the waves so he could bodysurf (always attached to his oxygen). He had to. We didn’t always have a special beach wheelchair that could get traction over the sand. But this summer, after the first day of walking out to the water, he said he couldn’t go back; it took too much out of him.

We did have a rented beach wheelbarrow that got me down to the waves that first day, and I told him he could hop on while someone pushed. But he said no. He was aware that he lacked the energy to handle the waves. And he knew he wasn’t up to getting overheated on the hot sand; his condition also compromised his temperature stability, so that once he became too hot or too cold, his body had a hard time readjusting to normal.

Mattie didn’t have the strength to climb Jockey’s Ridge, either, a massive sand dune in the middle of the Outer Banks that offers stunning views of the barrier island chain from the top. Park rangers drove us up in a jeep that year. He was still his charismatic self, chatting up the rangers and people who had hiked up to fly kites. But instead of turning cartwheels at the top, as he had done the year before, he sat on a lawn chair.

We treated all of Mattie’s limitations as challenges to be gotten around rather than game changers. Of course anybody could see that they were. But my aim was to help Mattie live on a day-to-day basis as though the assaults on his body could always be taken in stride, that any new weakening or new machinery were just part of life rather than shifts that called life into question. I even managed to convince myself much of the time that no symptom of illness was something a combination of medical help, ingenuity, and prayer couldn’t overcome.

Mattie was ahead of me, though. Even on the first day of that vacation, he let me know. For fun, he went around asking everyone why they had come to the beach house that summer, either videotaping their responses or writing them down. It was all note-taking for the Unsavable Graces book. Everyone gave silly answers. Sandy said she came to learn Braille for a course she was taking and not get sick; the summer before, she had come down with an awful case of bronchitis and was laid up most of the time. Nell said she had been planning on thinking three deep thoughts but had already done that in the car so was at a loss as to what she was going to do the rest of the week. Chris said he was a plumber and had come to fix the sink, code for being on the hunt for pretty girls.

Then I turned the tables and asked Mattie what he was there for, figuring he’d give as ridiculous an answer as everyone else. But he just looked at me and said, “I really need to consider the meaning of life this summer, because life is changing.”

Caught off guard and wanting to keep away from that subject, and not wanting to spoil the others’ fun, I chided him. “Mattie, we’re all clowning around, and you’re being serious and philosophical.” Immediately, I saw the hurt in his eyes—and have regretted to this day the words that fell out of my mouth at that moment. He was headed someplace else, even on day one.

Mattie remained ahead of me, however. After that exchange, he kept what he needed to say bottled up throughout the week, making sure his words mirrored the general festive mood. He jumped into as much physical activity as he could handle. He participated in the practical jokes. He played board games with the rest of us. Even when he had to take breaks more frequently than he used to, he would beg off joining in some group fun as casually as possible and go to his room to read or write poetry (and then end up falling asleep, even in the middle of the day—his fatigue was that overpowering). Not that he didn’t truly enjoy himself to the hilt. He did. But it wasn’t until our sunrise on the pier that he spoke his heart.

Sunrise on the pier was a ritual Mattie and I engaged in, without fail, the morning of our last full day at the beach every year. It was our thin space. A preacher once described thin space to me as that place where your spirit and God are in closest contact. Generally, we’re all aware we have a spirit, an essence, that’s deep inside us. At your thin space, the veil separating your essence from your being becomes transparent enough that the spirit becomes undeniable. Instead of being a silent voice, your spirit more or less shows itself to you; you know it intimately rather than simply being aware of it.

All of the beach was thin space for Mattie and me. Where we stayed on the Outer Banks was not an arcade-laden, honky-tonk resort spot with some sand and waves that happened to be nearby. It was where, on an island jutting into the ocean, the sea met the sky and the earth; past, present, and future converged in an absence ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherBerkley

- Publication date2010

- ISBN 10 0451231147

- ISBN 13 9780451231147

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages352

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Messenger: The Legacy of Mattie J.T. Stepanek and Heartsongs

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 0451231147-2-1

Messenger: The Legacy of Mattie J.T. Stepanek and Heartsongs

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-0451231147-new

Messenger: The Legacy of Mattie J.T. Stepanek and Heartsongs

Book Description Soft cover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # SC-01-920

Messenger: The Legacy of Mattie J.T. Stepanek and Heartsongs

Book Description Condition: New. . Seller Inventory # 52GZZZ01G9UO_ns

Messenger

Book Description paperback. Condition: New. Language: ENG. Seller Inventory # 9780451231147

Messenger: The Legacy of Mattie J.T. Stepanek and Heartsongs

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0451231147

Messenger: The Legacy of Mattie J.T. Stepanek and Heartsongs

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0451231147

Messenger: The Legacy of Mattie J. T. Stepanek and Heartsongs

Book Description Paperback. Condition: Brand New. reprint edition. 336 pages. 8.25x5.50x1.00 inches. In Stock. Seller Inventory # __0451231147

Messenger: The Legacy of Mattie J.T. Stepanek and Heartsongs

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0451231147

Messenger: The Legacy of Mattie J.T. Stepanek and Heartsongs

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0451231147