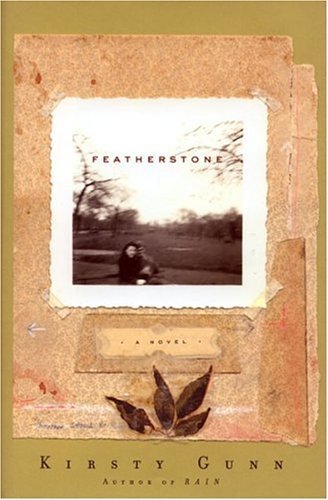

Items related to Featherstone

The mysterious disappearance and absence of a young woman from an isolated Scottish town have a profound impact on the lives of everyone she touched, but her possible homecoming could provide a catalyst for even more unsettling changes in their lives. By the author of Rain.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Kirsty Gunn is the author of several internationally acclaimed works of fiction, most recently the story collection This Place You Return to Is Home. Her first novel, Rain, was made into a feature film that was an official selection in 2002 at the Sundance and Cannes film festivals. She lives in London.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

Friday, early evening

one

He looked up and thought: I know you.

His hands were still in earth, where it was warm, but he withdrew them,

brought them up to shade his eyes. He looked, with his hands at his

forehead that way against the light, and he thought he did know her, though

the light was bright on her, and around her bright, and at her back, like foil.

It

was late, late afternoon.

The sun, however, that was a thing he hadn"t noticed before. Though he had

been out in his garden for most of the day, Johanssen had no reason to be

looking at the weather. To kneel on the stiff, sweet-smelling sack he always

used for work, to sift with his fingers through the freshly dug flower beds –

this was all he had to do: no need to worry then about the light and time

around him. Yet now, in the moment of bringing his hands up out of the

earth,

and the late summer sun suddenly low in the sky and too bright to see, and

with the air on his thin, naked arms cooling to cold, though these weren"t

his

thoughts – coolness, the slight damp chill of the open air – though these

weren"t his thoughts, when the voice came across to him out of the light he

registered then, in that moment, the small drop of temperature and his body

felt old then, he became very old when he heard her voice coming across to

him from out of the light:

"Uncle Sonny, it"s me."

Thurson Johanssen was an old man, he didn"t need cold air to tell him. Of

course he was old, he had an old man"s name, but no one called him it. He

was old but still they gave him the other name, a great name he could

figure,

a name for someone who was only a boy.

"Hey, Son," they said to him.

"What"s up, Sonny?"

That was how they were with him, and he always enjoyed it.

There

was a lightness in their voices when they said the boy"s name.

"Great garden again this year, Sonny Jim," they said, and they

gave him such pleasure then, with their friendly voices.

"Your flowers, Sonny. They"re always the prettiest in town."

It was true that he did so love the garden. He loved it in all its parts

because,

he could figure, all old men must love their gardens, though he"d had this

one

since he was a boy. He had been young like a boy when he"d begun with it,

when Nona had helped him with the tiny branches and the blossom, yet still

he loved the garden now like it was new, loved it in all the parts he could

come to because, he supposed, it was a reminder of her, this place where

his sister had first showed him how to let things grow. There was the part

where the flowers had been thick, waist-high all summer in a kind of cloud,

the forget-me-nots and Queen Anne"s lace, and the tall pale-coloured

poppies

he favoured best, pale like skins with their dark in the centre like a mouth or

an eye, with their black dust. He was in that part now, where they had

grown,

making the earth soft again for a new planting, smoothing down the ground

as if smoothing down paper to draw, the lines and shallow dips for flowers,

marking with his fingertip a place for a seed.

Of course, Francie would know he"d be in his garden this time.

She would remember, even after all these years.

"There"s no skill to a garden, there"s no talent in it" – that"s what

he always said to anybody, if they talked to him about it. "It"s just a

question

of timing."

There was spring. Summer. Then autumn again. The long winter

again . . . Certain times of year held certain things to be done, that was all,

and she would know that, Johanssen could figure. She would remember.

That

with the poppies long gone and the little dry roots of lobelia weightless in

the

palm of his hand, he"d be somewhere in the garden now, digging over the

beds, pulling out the dead plants free.

Francie would always know the way he did things, where he would be, in

what part. She might have been down the back already, to look for him

there,

because he did love that part too. This time of year he could easily have

been

working there, where the grass was flat and soft and the roses grew so

thick

over the fence that they covered the tiny barbs in the wire that could cut

you.

Or further down, where the small orchard went into woods, into the willows,

those trees familiar and dense and known to him but even so, when he went

out there at night sometimes, after he got back from the pub, say, went out

into the willows for a pee he might get lost, kind of, for a little while when it

was dark, or late, or if he"d had too much to drink, maybe. Rhett would be

with him, sniffing around, he might growl a little just at some small sound,

and Johanssen would watch him, thinking all the while he knew exactly

where they were both standing. Then, after he"d buttoned himself up, he"d

be

looking around and see only the thin trunks of willows on every side, there

would be no pattern in them, and that"s when he"d be lost then, like a boy

might get lost, or a young man might. All the same, he loved it down in this

part of the garden too. Even as the willows kept growing, green stalks that

kept coming out of the ground every spring, like wands, and he couldn"t

stop

them. It was because he was home there. Of course she would always

know

he"d be home there.

And yet . . .

There was this part of the garden where he was now, where he

was kneeling, and there had been her voice, then his looking up . . .

And though she must have known that all the time he was looking

and looking into the light to see her, he was looking to see but he couldn"t

see. Only the sun, printing gold into black into gold against his eyes, only a

dark shape against the sky, like a dear shape cut clean out of the light and

laid against it . . .

I know you.

And then she was gone.

Slowly Johanssen got himself up from the ground. Stood himself up,

straightened, and behind him somewhere Rhett shifted then was up on his

feet like a young dog to follow. Together they walked the few paces over to

the hedge at the side of the road, and stood, waiting at the hedge, but

nobody there down the road, nobody. Perhaps she had turned the corner

already, down at the end by the petrol pump and round the hotel into Main

Street. Or maybe she had run the other way, past Bryson"s, past the

Grahams", down past Nona"s old place and then round the corner by the

pine

trees and gone.

Even so, they stayed, Johanssen"s eyes along the road, up and down,

Rhett

with his muzzle pointing up into the slight breeze as if he, too, was waiting.

"Where did she go, eh?"

Johanssen put his hand to the dog"s soft head, touched an ear

that was soft.

"Where did she go just when I could have got up to meet her?"

He fondled the dog"s ear, like a fold of soft cloth between his

fingers.

"Where did she go, eh? Old boy? Where is she now?"

And in time, the dog sat, lay down, a great sigh escaping from

him, like from a bag, and still there was an old man, standing, looking into

nothing, just the same empty road, but it was warmer there, out of the

shadow where he"d been kneeling, now that he was standing in the light the

sun seemed warm again on his back, on his dirt-stained arms.

*

Johanssen could guess there were any number of places a person could

run

to in this town. Not even a town, most people would say, but you wouldn"t

call it a village either. That wasn"t the right word. Village would make it

something different again, so town would have to do it, though the place

was

small. People said they were going "up town" like they were going into

London or New York, a queer way of putting it when you were just after the

milk, or a packet of tobacco papers, but people said "up town" just the

same.

There was the main street, the Railton Hotel on the corner and the stretch

of

shops beyond it, a few streets going off either side. Even so, the place was

big enough that you could be private if you needed. Big enough that you

wouldn"t have to leave.

Johanssen had never felt he"d had to leave.

He was someone who had lived all his life in this one town. He had never

gone away. He had been born here, gone to school and grown up here.

Found work and retired, and even though he"d never married, stayed fixed in

his ways, maybe, with his sister"s house up the road he could go to, and

young Francie coming to him every day with her songs, and her stories

from

school, still he could tell anyone anything about the place they might want

to

know, the different ways to get around. Like where the roads were good, for

example, if you had a car, or if you were walking along then he knew where

the grass verges grew thick enough that you could climb up onto them if a

big lorry came by. He could tell you where fences were broken, or where

there were cracks in the concrete where the gravel showed through. Or

where

there were cattle grids that were hard to walk on, or drains where you could

lose money . . . plenty of places where you could lose money.

A person returning to town might need to know about that kind of thing,

Johanssen could figure. They would want to be reminded of where they

could

safely walk, and of shops where they could spend their money. Like

Dalgety"s on the main street, where they had the smart clothes and the

packages of books ordered in from the city, with silken threads to mark

where you"d stopped reading and the thick, shiny paper covers. They might

need to know about places like that, or like the post office and the bank and

how they were also in the main street of town. That was a well-kept road. If

you went along it to the end you came to the hall where they sometimes

had

dances, and then there were the showgrounds over the bridge just beyond,

and that was somewhere that always had plenty going on, rugby games,

the

country A&P in summer. There was everything here, everything. So why

feel

it wasn"t enough to stay, that you"d have to leave, go searching out for

more?

And yet, that"s what Francie had done, and as Johanssen stood waiting,

the

memory returned to him from all those years ago, of the town suddenly

being

full of streets and roads that instead of taking you to places that you knew,

only took you away. They were paths and exits and routes marked "To the

North", "To the South", and they were like a map of little scars, like the lines

rubbed with dirt on the palms of Sonny"s hands that showed how you

couldn"t

bring people back, not even when Nona was buried, and flowers and earth

piled over her like a bed yet still she was cold and wanted Francie there . . .

No, by then Sonny knew there were certain roads you could lose yourself if

you wanted, you could hide. You could be deep in the high country on a

twisting, empty, unsealed track, or lost in traffic on a four-lane highway.

Either way, you weren"t coming back. Even the little slip-way out of town

Johanssen had helped seal, from his days as a working man, was

somewhere you could disappear if you wanted. You would simply drive

down

that tiny road to the gate, open the gate, close it behind you, and it would

be

like you were nowhere in the world. You"d go deeper and deeper into trees,

following a grass towpath all the way down through the Reserve to the river.

It

could get muddy there in winter, and dangerous to drive if the water was

high,

but still the council kept the undergrowth back so there was always a clear

path and space enough amongst the trees to park a car. It was somewhere

Ray Weldon often went, Johanssen knew, and he was fond of Ray.

That wasn"t a place, though, for most people. It was too dark,

even in high summer, and shadowy mostly with water and leaves.

Johanssen

himself would never go there. He would just carry on down the sealed road

half a mile past the river turn-off, ignoring that sign; he would just keep

going

straight ahead to where the road eventually brought you back again to the

outskirts of town. Bob Alexander"s garage was along that way, a nice place

sitting outside in the sun, where he did the mechanics and electricals, and

the Carmichaels" lumber yard opposite, though Johnny Carmichael always

said he was going to move from there, because he was too near the holy

cross of the church for his liking, didn"t want the minister hearing him

swear.

"Too damn near," Johnny Carmichael would say, proudly, and it

was like Johanssen could hear the scream of the cutting timber in the

background whenever Johnny shouted, whisky on his breath.

"For the Carmichaels," he would shout. "Too damn near, and their

wild ways."

Johanssen laughed a bit, just then, thinking about Johnny and how he

talked

so big.

"Got a load on today . . ." His eyes would be blue as blue, and his

hair still black from where he used the grease. ". . . but nothing my

horsepower can"t handle."

It was like Johnny and the Carmichaels thought they were princes

of the place sometimes, the way they might swagger about, and give on as

if

they knew things other people couldn"t, about strengths or weights, or

money, when all the time they were just like everybody else and probably

guessing.

Even so, as he stood there by the hedge in the last of the afternoon sun,

Johanssen thought he might ask Johnny tonight, if he"d noticed anybody

new

arriving in town, a young woman. He could ask Johnny or Gaye, or any of

their boys. The boys would probably be the best ones to ask, always out on

the lookout for things happening, driving around in their father"s beat-up old

trucks and pick-ups, doing all the picking up anyone could handle.

Johanssen laughed again a bit, at that, a kind of a joke he"d made, and

thinking of those Carmichael boys. He would see them tonight, no doubt,

and

their father; he"d ask them all when he saw them at the Railton Bar tonight.

Had they seen . . . he would ask.

And he"d ask Margaret behind the bar, too.

"Funny thing," he might say then, when Margaret had his glass put out

before

him, and when his first sip had been taken from it. "Funny thing . . ."

And he would wipe the wetness of the beer from his mouth with

the back of his hand, or with a handkerchief even, but all the time keeping it

casual, acting very casual.

"This afternoon," he would say, and he would take another small

sip of beer.

"Thought I saw someone I haven"t seen in a long while."

"Thought I saw Nona"s little girl."

Copyright © 2002 by Kirsty Gunn. Reprinted by permission of Houghton

Mifflin Company.

one

He looked up and thought: I know you.

His hands were still in earth, where it was warm, but he withdrew them,

brought them up to shade his eyes. He looked, with his hands at his

forehead that way against the light, and he thought he did know her, though

the light was bright on her, and around her bright, and at her back, like foil.

It

was late, late afternoon.

The sun, however, that was a thing he hadn"t noticed before. Though he had

been out in his garden for most of the day, Johanssen had no reason to be

looking at the weather. To kneel on the stiff, sweet-smelling sack he always

used for work, to sift with his fingers through the freshly dug flower beds –

this was all he had to do: no need to worry then about the light and time

around him. Yet now, in the moment of bringing his hands up out of the

earth,

and the late summer sun suddenly low in the sky and too bright to see, and

with the air on his thin, naked arms cooling to cold, though these weren"t

his

thoughts – coolness, the slight damp chill of the open air – though these

weren"t his thoughts, when the voice came across to him out of the light he

registered then, in that moment, the small drop of temperature and his body

felt old then, he became very old when he heard her voice coming across to

him from out of the light:

"Uncle Sonny, it"s me."

Thurson Johanssen was an old man, he didn"t need cold air to tell him. Of

course he was old, he had an old man"s name, but no one called him it. He

was old but still they gave him the other name, a great name he could

figure,

a name for someone who was only a boy.

"Hey, Son," they said to him.

"What"s up, Sonny?"

That was how they were with him, and he always enjoyed it.

There

was a lightness in their voices when they said the boy"s name.

"Great garden again this year, Sonny Jim," they said, and they

gave him such pleasure then, with their friendly voices.

"Your flowers, Sonny. They"re always the prettiest in town."

It was true that he did so love the garden. He loved it in all its parts

because,

he could figure, all old men must love their gardens, though he"d had this

one

since he was a boy. He had been young like a boy when he"d begun with it,

when Nona had helped him with the tiny branches and the blossom, yet still

he loved the garden now like it was new, loved it in all the parts he could

come to because, he supposed, it was a reminder of her, this place where

his sister had first showed him how to let things grow. There was the part

where the flowers had been thick, waist-high all summer in a kind of cloud,

the forget-me-nots and Queen Anne"s lace, and the tall pale-coloured

poppies

he favoured best, pale like skins with their dark in the centre like a mouth or

an eye, with their black dust. He was in that part now, where they had

grown,

making the earth soft again for a new planting, smoothing down the ground

as if smoothing down paper to draw, the lines and shallow dips for flowers,

marking with his fingertip a place for a seed.

Of course, Francie would know he"d be in his garden this time.

She would remember, even after all these years.

"There"s no skill to a garden, there"s no talent in it" – that"s what

he always said to anybody, if they talked to him about it. "It"s just a

question

of timing."

There was spring. Summer. Then autumn again. The long winter

again . . . Certain times of year held certain things to be done, that was all,

and she would know that, Johanssen could figure. She would remember.

That

with the poppies long gone and the little dry roots of lobelia weightless in

the

palm of his hand, he"d be somewhere in the garden now, digging over the

beds, pulling out the dead plants free.

Francie would always know the way he did things, where he would be, in

what part. She might have been down the back already, to look for him

there,

because he did love that part too. This time of year he could easily have

been

working there, where the grass was flat and soft and the roses grew so

thick

over the fence that they covered the tiny barbs in the wire that could cut

you.

Or further down, where the small orchard went into woods, into the willows,

those trees familiar and dense and known to him but even so, when he went

out there at night sometimes, after he got back from the pub, say, went out

into the willows for a pee he might get lost, kind of, for a little while when it

was dark, or late, or if he"d had too much to drink, maybe. Rhett would be

with him, sniffing around, he might growl a little just at some small sound,

and Johanssen would watch him, thinking all the while he knew exactly

where they were both standing. Then, after he"d buttoned himself up, he"d

be

looking around and see only the thin trunks of willows on every side, there

would be no pattern in them, and that"s when he"d be lost then, like a boy

might get lost, or a young man might. All the same, he loved it down in this

part of the garden too. Even as the willows kept growing, green stalks that

kept coming out of the ground every spring, like wands, and he couldn"t

stop

them. It was because he was home there. Of course she would always

know

he"d be home there.

And yet . . .

There was this part of the garden where he was now, where he

was kneeling, and there had been her voice, then his looking up . . .

And though she must have known that all the time he was looking

and looking into the light to see her, he was looking to see but he couldn"t

see. Only the sun, printing gold into black into gold against his eyes, only a

dark shape against the sky, like a dear shape cut clean out of the light and

laid against it . . .

I know you.

And then she was gone.

Slowly Johanssen got himself up from the ground. Stood himself up,

straightened, and behind him somewhere Rhett shifted then was up on his

feet like a young dog to follow. Together they walked the few paces over to

the hedge at the side of the road, and stood, waiting at the hedge, but

nobody there down the road, nobody. Perhaps she had turned the corner

already, down at the end by the petrol pump and round the hotel into Main

Street. Or maybe she had run the other way, past Bryson"s, past the

Grahams", down past Nona"s old place and then round the corner by the

pine

trees and gone.

Even so, they stayed, Johanssen"s eyes along the road, up and down,

Rhett

with his muzzle pointing up into the slight breeze as if he, too, was waiting.

"Where did she go, eh?"

Johanssen put his hand to the dog"s soft head, touched an ear

that was soft.

"Where did she go just when I could have got up to meet her?"

He fondled the dog"s ear, like a fold of soft cloth between his

fingers.

"Where did she go, eh? Old boy? Where is she now?"

And in time, the dog sat, lay down, a great sigh escaping from

him, like from a bag, and still there was an old man, standing, looking into

nothing, just the same empty road, but it was warmer there, out of the

shadow where he"d been kneeling, now that he was standing in the light the

sun seemed warm again on his back, on his dirt-stained arms.

*

Johanssen could guess there were any number of places a person could

run

to in this town. Not even a town, most people would say, but you wouldn"t

call it a village either. That wasn"t the right word. Village would make it

something different again, so town would have to do it, though the place

was

small. People said they were going "up town" like they were going into

London or New York, a queer way of putting it when you were just after the

milk, or a packet of tobacco papers, but people said "up town" just the

same.

There was the main street, the Railton Hotel on the corner and the stretch

of

shops beyond it, a few streets going off either side. Even so, the place was

big enough that you could be private if you needed. Big enough that you

wouldn"t have to leave.

Johanssen had never felt he"d had to leave.

He was someone who had lived all his life in this one town. He had never

gone away. He had been born here, gone to school and grown up here.

Found work and retired, and even though he"d never married, stayed fixed in

his ways, maybe, with his sister"s house up the road he could go to, and

young Francie coming to him every day with her songs, and her stories

from

school, still he could tell anyone anything about the place they might want

to

know, the different ways to get around. Like where the roads were good, for

example, if you had a car, or if you were walking along then he knew where

the grass verges grew thick enough that you could climb up onto them if a

big lorry came by. He could tell you where fences were broken, or where

there were cracks in the concrete where the gravel showed through. Or

where

there were cattle grids that were hard to walk on, or drains where you could

lose money . . . plenty of places where you could lose money.

A person returning to town might need to know about that kind of thing,

Johanssen could figure. They would want to be reminded of where they

could

safely walk, and of shops where they could spend their money. Like

Dalgety"s on the main street, where they had the smart clothes and the

packages of books ordered in from the city, with silken threads to mark

where you"d stopped reading and the thick, shiny paper covers. They might

need to know about places like that, or like the post office and the bank and

how they were also in the main street of town. That was a well-kept road. If

you went along it to the end you came to the hall where they sometimes

had

dances, and then there were the showgrounds over the bridge just beyond,

and that was somewhere that always had plenty going on, rugby games,

the

country A&P in summer. There was everything here, everything. So why

feel

it wasn"t enough to stay, that you"d have to leave, go searching out for

more?

And yet, that"s what Francie had done, and as Johanssen stood waiting,

the

memory returned to him from all those years ago, of the town suddenly

being

full of streets and roads that instead of taking you to places that you knew,

only took you away. They were paths and exits and routes marked "To the

North", "To the South", and they were like a map of little scars, like the lines

rubbed with dirt on the palms of Sonny"s hands that showed how you

couldn"t

bring people back, not even when Nona was buried, and flowers and earth

piled over her like a bed yet still she was cold and wanted Francie there . . .

No, by then Sonny knew there were certain roads you could lose yourself if

you wanted, you could hide. You could be deep in the high country on a

twisting, empty, unsealed track, or lost in traffic on a four-lane highway.

Either way, you weren"t coming back. Even the little slip-way out of town

Johanssen had helped seal, from his days as a working man, was

somewhere you could disappear if you wanted. You would simply drive

down

that tiny road to the gate, open the gate, close it behind you, and it would

be

like you were nowhere in the world. You"d go deeper and deeper into trees,

following a grass towpath all the way down through the Reserve to the river.

It

could get muddy there in winter, and dangerous to drive if the water was

high,

but still the council kept the undergrowth back so there was always a clear

path and space enough amongst the trees to park a car. It was somewhere

Ray Weldon often went, Johanssen knew, and he was fond of Ray.

That wasn"t a place, though, for most people. It was too dark,

even in high summer, and shadowy mostly with water and leaves.

Johanssen

himself would never go there. He would just carry on down the sealed road

half a mile past the river turn-off, ignoring that sign; he would just keep

going

straight ahead to where the road eventually brought you back again to the

outskirts of town. Bob Alexander"s garage was along that way, a nice place

sitting outside in the sun, where he did the mechanics and electricals, and

the Carmichaels" lumber yard opposite, though Johnny Carmichael always

said he was going to move from there, because he was too near the holy

cross of the church for his liking, didn"t want the minister hearing him

swear.

"Too damn near," Johnny Carmichael would say, proudly, and it

was like Johanssen could hear the scream of the cutting timber in the

background whenever Johnny shouted, whisky on his breath.

"For the Carmichaels," he would shout. "Too damn near, and their

wild ways."

Johanssen laughed a bit, just then, thinking about Johnny and how he

talked

so big.

"Got a load on today . . ." His eyes would be blue as blue, and his

hair still black from where he used the grease. ". . . but nothing my

horsepower can"t handle."

It was like Johnny and the Carmichaels thought they were princes

of the place sometimes, the way they might swagger about, and give on as

if

they knew things other people couldn"t, about strengths or weights, or

money, when all the time they were just like everybody else and probably

guessing.

Even so, as he stood there by the hedge in the last of the afternoon sun,

Johanssen thought he might ask Johnny tonight, if he"d noticed anybody

new

arriving in town, a young woman. He could ask Johnny or Gaye, or any of

their boys. The boys would probably be the best ones to ask, always out on

the lookout for things happening, driving around in their father"s beat-up old

trucks and pick-ups, doing all the picking up anyone could handle.

Johanssen laughed again a bit, at that, a kind of a joke he"d made, and

thinking of those Carmichael boys. He would see them tonight, no doubt,

and

their father; he"d ask them all when he saw them at the Railton Bar tonight.

Had they seen . . . he would ask.

And he"d ask Margaret behind the bar, too.

"Funny thing," he might say then, when Margaret had his glass put out

before

him, and when his first sip had been taken from it. "Funny thing . . ."

And he would wipe the wetness of the beer from his mouth with

the back of his hand, or with a handkerchief even, but all the time keeping it

casual, acting very casual.

"This afternoon," he would say, and he would take another small

sip of beer.

"Thought I saw someone I haven"t seen in a long while."

"Thought I saw Nona"s little girl."

Copyright © 2002 by Kirsty Gunn. Reprinted by permission of Houghton

Mifflin Company.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHoughton Mifflin Harcourt

- Publication date2003

- ISBN 10 0618246924

- ISBN 13 9780618246922

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages256

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 58.81

Shipping:

US$ 4.88

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

FEATHERSTONE

Published by

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

(2003)

ISBN 10: 0618246924

ISBN 13: 9780618246922

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.01. Seller Inventory # Q-0618246924

Buy New

US$ 58.81

Convert currency