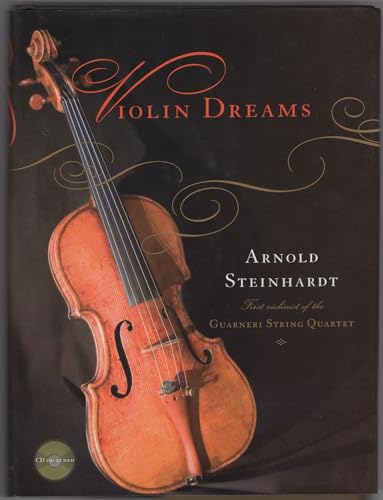

Items related to Violin Dreams

Arnold Steinhardt, for more than forty years an international soloist and the first violinist of the Guarneri String Quartet, brings warmth, wit, and fascinating insider details to the story of his lifelong obsession with the violin, that most seductive and stunningly beautiful instrument. His story is rich with vivid scenes: the terror inflicted by his early violin teachers, the sensual pleasure involved in the pursuit of the perfect violin, the charged atmosphere of high-level competitions. Steinhardt describes Bach’s Chaconne as the holy grail for the solo violin, and he illuminates, from the perspective of an ardent owner of a great Storioni violin, the history and mysteries of the renowned Italian violinmakers.

Violin Dreams includes a remarkable CD recording of Steinhardt performing Bach’s Partita in D Minor as a young violinist forty years ago and playing the same piece especially for this book. A conversation between the author and Alan Alda on the differences between the two performances is included in the liner notes.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Onstage, please,” someone called out in the half-light. Standing in the wings of Carnegie Hall, I felt my heart racing and the palms of my hands turning clammy. The stage door swung open slowly, framing the broad expanse of hardwood floor where, in a matter of seconds, I would play Johann Sebastian Bach’s Chaconne for solo violin. Doubts rushed at me like a fetid wind. Would I play well? Would the listeners, music lovers with exacting expectations, be pleased? Or might I be booed for a less than stellar rendition of the great Chaconne? Then I thought the unthinkable: Just don’t play. It was my choice, after all. Either cross the Rubicon onto the heady but risky concert stage or cancel the performance entirely, something akin to jilting your bride at the altar.

As if by alchemy, a delicious anticipation unexpectedly rose up in me, quelling my fears. Of course I would play! I strode onto Carnegie’s stage, savoring tiers of seats stacked dizzyingly one on top of the other. The hall’s grandeur swept any lingering nerves away, but the applause that I expected to float forward was absent. An eerie silence greeted my entrance from the wings, and when I looked out over the stage, my heart sank. There was no audience at all. Carnegie Hall, lit on every level by strings of shimmering lights, stood empty, like a great ocean liner at dock awaiting passengers before a voyage. Only when lowering my gaze a notch did I notice that a few people were indeed occupying the front row’s center section. Curiously enough, they all had writing pads and pencils ready.

Thank you for coming, Mr. Steinhardt,” a man with a salt-and- pepper mustache who sat on the aisle called out. We would like to ask you questions about the violin.” Before I could respond, a woman with a cigarette in her hand leaned forward and spoke. Would you tell us about the violin’s early history?” Apparently this self-appointed jury was bent on going through with some kind of examination. Better to humor these people and get on with my recital. After all, the audience had not yet arrived.

I began to think out loud. Let’s see. Antonio Stradivari was the most famous. He studied with Nicholas Amati. Amati was one of the early violinmakers. Then there was Maggini. Was he the first?” The woman eyed me coolly and chose not to answer. A frigid silence lifted off the entire group as I stood at the front of the stage looking down on them.

The man spoke again. Please tell us about the string instruments leading up to the violin the rebec, the hurdy-gurdy, and the crwth.” The names were familiar to me, but I was forced to admit the truth. I can’t tell you anything about the rebec, the hurdy-gurdy, or the . . .” Without a vowel to move the consonants along, my tongue snagged on crwth as if I were afflicted by a speech impediment. My face flushed with shame.

This must have been the last straw, for the entire group of judges rose and began to talk among themselves. I searched frantically in my mind for a way to dispense with these people who had entered my life like a rogue asteroid.

Then the obvious occurred to me. I would simply play the Chaconne as planned. Let Bach’s noble opening strains answer the criticism of my tormentors and banish them from the hall! But when I tried to lift the violin onto my shoulder, it became unbearably heavy, and the bow refused to move across the strings, as if a quick-setting glue had been applied to its horsehair. The Chaconne’s opening three- and four-note chords should have been easy enough to play, but to my mounting consternation, only a strangled croak came out of the violin. From the corner of my eye I saw the man with the mustache collecting pads. He mounted the stage steps slowly.

A feeling of suffocating dread rose up in me, and then I awoke. Carnegie Hall, my violin recital, even the panel of judges who moments earlier had held me hostage, were gone. To my immense relief, the concert-exam was only an anxiety dream, one of dozens I’ve had over the years.

The bright morning light nudged my sleep-laden eyes open and I slowly got out of bed. Even in my early-morning stupor, I understood one thing. I had dreamed about the Chaconne because I was about to play it. A dear friend, Petra Shattuck, had just died unexpectedly, leaving a large family grieving for her. A few days ago, her husband, John, had called and asked me to play at her memorial service. Bach’s Chaconne, solemn and ceremonial, seemed a fitting choice for all of us who mourned her. Whether played separately or as the last of the D Minor Partita’s five movements, the Chaconne stood out as a towering and emotion- charged work. It reminded me of a mighty cathedral impposing in length, moving and uplifting in spirit, and exquisite in its details.

To prepare for Petra’s service, I had been practicinggggg the Chaconne every day fussing over individual phrases, searching for better ways to string them together, and wondering about the very nature of the piece, at its core an old dance form that had been around for centuries. After the many times I had heard and played the Chaconne, I had hoped it would fall relatively easily into place by now, but it appeared to be taunting me. The more I worked, the more I saw; the more I saw, the further away it drifted from my grasp. Perhaps that is in the nature of every masterpiece. But more than that, the Chaconne seemed to exude shadows over its grandeur and artful design. Exactly what was hidden there I could not say, but I would lose myself for long stretches of time exploring the work’s repeating four-bar phrases, which rose and fell and marched solemnly forward in ever-changing patterns. The upcoming performance for Petra clearly weighed on me. Why else would the Chaconne worm its way into my nocturnal wanderings?

An hour later, hurrying down the hall of Rutgers University’s Mason Gross School of the Arts, where I have taught for many years, I passed the studios of Susan Starr, concert pianist, and Doug Johnson, music historian. Ah the woman with the cigarette, the man with the salt- and-pepper mustache! We faculty members recently had lobbed questions at a squirming violinist undergoing his final oral exam. Most of what we had asked covered ground I knew intimately about the repertoire for the instrument, but some questions about the violin itself had stumped me. I emerged from the exam room feeling vaguely uncomfortable. If I myself knew so little about the violin’s origins, what right did I have to judge this young student?

Was my life too busy, was sheer sloth the culprit, or did the violin interest me only as a conduit for the music I played? After all, nobody expected a carpenter to know the hammer and saw’s history. Odd, though, wasn’t it, for me to be so ill-informed about an instrument that demanded such intimacy? When I hold the violin, my left arm stretches lovingly around its neck, my right hand draws the bow across the strings like a caress, and the violin itself is tucked under my chin, a place halfway between my brain and my beating heart. Instruments that are played at arm’s length the piano, the bassoon, the tympani have a certain reserve built into the relationship. Touch me, hold me if you must, but don’t get too close, they seem to say. To play the violin, however, I must stroke its strings and embrace a delicate body with ample curves and a scroll like a perfect hairdo fresh from the beauty salon. This creature sings ardently to me day after day, year after year, as I embrace it. Shouldn’t I want to know something about it?

But these are grownup thoughts, whereas my violin study began with a child’s perspective. At the age of six, the dawn of my awareness, I accepted all the wonders of life my beloved toy train, the fairy tales that frightened me, a butterfly’s miraculous flight, and even the first magical sounds of my violin at face value. When I rode my bicycle down the block, the thrill of its motion and the joy of having finally learned to ride it were what interested me, not the bicycle’s design or history. Why would I think any differently about the violin when I was learning to hold it and make it do my bidding? Unlike a lawyer, firefighter, or bus driver, who begins and ends his or her career as an adult, I am still inhabited by that unquestioning child who began violin study many years ago.

All morning long that day at Rutgers I worked with my violin students. I heard the things that violin lessons are made of scales, études, Bach, Mozart, Paganini. Hanfang Jiang, a gifted student from China, played Bartók’s First Rhapsody for me. Hanfang played well, very well, and I was pleased with her progress, but did she know when the violin had come into being and who the first violinmakers were?

When lunchtime arrived, I walked over to the school library with my sandwich and thermos and began pulling books about stringed instruments off the shelves. Reflexively, I looked around for my dream’s tormentors. Isn’t it a little late? I imagined my anxiety- dream judges snickering at my attempts to learn about the violin some sixty years after taking it up.

I came across illustrations of two early bowed instruments from India, the ravanastron and the omerti, each made of a hollowed cylinder of sycamore wood and played in the manner of a cello. The primal simplicity of the violin’s ancestors was breathtaking: a sounding box, a stick attached to it, and a couple of strings stretched across the structure. Any one of us could approximate it with some spare wood, a knife, and a little time to kill. It seemed only a step or two removed from the most primitive attempts at an instrument. The early hunters could not have failed to notice the twang of a bowstring as it drove the arrow toward its unsuspecting prey. I imagined the hunting party later that evening, gorged on the kill, recounting stories of its conquests by the campfire. Some sated cave dweller, motivated perhaps by idle curiosity, stretched a thin strip of cast-aside animal skin over a hollow gourd and plucked it absentmindedly with one finger. He raised his eyebrows in mild astonishment at the reverberant sound. A new musical instrument, the prototype of the guitar, the banjo, the mandolin, the balalaika, might have been born that evening as the fire’s embers died away.

The ravanastron illustration also showed its mate, a bow of the most basic kind nothing more than a slender, curved piece of wood with a string attached at both sides, but still recognizable as a distant cousin of today’s violin bow. It has been said that the history of the violin is really the history of the bow. When I draw my bow across the violin’s strings and coax out a sustained sound, a small miracle takes place. As if by magic, my gesture is able to produce an astonishing range of sounds akin to the human voice. The bow is a magic wand that sets the violin apart from plucked instruments. The accomplished guitarist creates the illusion of sustained sound by grouping notes together that individually die. But if my bow arm is in good working order, I need no such subterfuge. Germans call the violin a stroke” instrument, an apt name, considering what the bow does.

But I have more difficulty imagining a script for the bow’s Eve than the violin’s Adam. Back at the same campfire after the hunt, how did the tribe’s musical-instrument inventor get the idea of stroking his musical string rather than plucking it? In response to his mate’s complaints about that awful twanging sound, he might have taken a smooth piece of cane or reed left over from a woven basket and drawn it across the strings. Perhaps he even notched it, if the sound proved insufficient one of the innumerable little breakthroughs, along with myriad failures and dead ends, that culminated in the elegant object made of pernambucco and ebony wood, ivory, silver, mother-of-pearl, and horsehair that I hold in my right hand every time I hold the violin with my left.

I glanced again at the ravanastron illustration and realized with a start that I’d seen something like it recently in the New York City subway, of all places. While changing trains at Times Square station in rush hour, I thought I heard a violin above the din. A small crowd had gathered around a young Chinese man who sat between the express and local train tracks, playing with great energy on a cellolike two-stringed instrument. It sounded like a violin run amuck the pitch rising and falling wildly, the vibrato frenzied, the music passionate. Despite his instrument’s foreignness, the sliding connections between notes and minute inflections of bowing were the completely familiar gestures of my string world. I stood transfixed in the crowd, listening to what was unmistakably virtuoso playing. When the music came to an end, the crowd clapped enthusiastically and began to disperse.

I lingered out of something more than curiosity. We belonged to the same fraternal order, so to speak. We were both string players. When our eyes met, I mimicked the motions of a violinist and then pointed to my own body. The man’s face lit up. I play the urheen, an ancient instrument from China, where I was born,” he said in clear English. Here you sometimes call it a Chinese fiddle. Sit down!” With that, the man abruptly stood up and pulled me over to the stool on which he had been playing. No, no, no,” I protested, but to no avail. In a series of deft motions, he pushed me onto the stool and handed me his instrument and bow. Play,” he commanded, grinning widely. No, no,” I repeated more urgently. More or less the same group of people again collected around us to see what the fuss was about. It had taken only several seconds, ten at most, for me to be transformed from amused bystander to the main attraction. What had I gotten myself into?

I do not play the cello and I certainly don’t know how to play the urheen, but the man seemed unconcerned about those insignificant details. He gave me a lesson on the spot even as I said No, no” for the third time by guiding both my hands on the instrument with his. To my amazement, a passable sound came out of the urheen and the crowd clapped once again. The rumble of an approaching train provided the excuse I needed to hand the instrument back and get up. This time it was the urheen player’s turn to say No, no,” and we both laughed as I boarded the N train. An American violinist and a Chinese fiddler eyed one another with a sense of newfound familiarity through the closing doors.

I returned to my book and flipped the page. As if by command, an illustration of the urheen stared up at me. Next to it was a picture of the modern Turkish or Arabian kemangeh a’gouz, a ravanastron-like instrument. I looked at the kemangeh, meaning ancient bowed instrument” in Persian, and wondered why it was familiar to me. After all, I had never paid much attention to any of the instruments featured in this dry textbook. Then I remembered the Azerbaijani taxi driver who had recently picked me up at La Guardia Airport. He looked at my instrument case as I got into the cab and asked what was inside. Half an hour later, I paid him in front of my apartment building. Once again he looked at the violin case in my hand, and then he glared at me accusingly. Can you crrry on the violin?” he demanded to know. I was taken aback. In my country they have such a crrrying instrument, the kemangeh. You can really crrry on it. Can you crrry on that?” I assured him that I could, would, and have cried on the violin. The driver must have realized as we stood facing one another by the still-open trunk of his taxi that a winner in the crying contest would never be decided this way. Suddenly he opened his mouth wide and began a vocal imitation of his native instrument, accompanied by the flailing arm movements of a kemange...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHoughton Mifflin Harcourt

- Publication date2006

- ISBN 10 0618368922

- ISBN 13 9780618368921

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages255

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Violin Dreams

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0618368922

Violin Dreams

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon0618368922

Violin Dreams

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0618368922

Violin Dreams

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0618368922

Violin Dreams

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Brand New Copy. Seller Inventory # BBB_new0618368922

Violin Dreams

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. 1.05. Seller Inventory # 0618368922-2-1

Violin Dreams

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published 1.05. Seller Inventory # 353-0618368922-new

Violin Dreams

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0618368922

Violin Dreams

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks186379

VIOLIN DREAMS

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.06. Seller Inventory # Q-0618368922