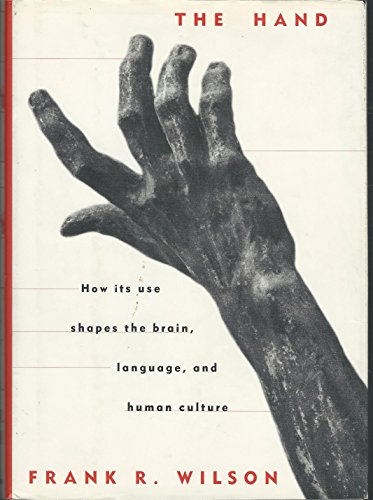

Items related to The Hand: How its use shapes the brain, language, and...

Synopsis

"The human hand is so beautifully formed, its actions are so powerful, so free and yet so delicate that there is no thought of its complexity as an instrument; we use it as we draw our breath, unconsciously." With these words written in 1833, Sir Charles Bell expressed the central theme of some of the most far-reaching and exciting research being done in science today. For humans, the lifelong apprenticeship with the hand begins at birth. We are guided by our hands, and we are indelibly shaped by the knowledge that comes to us through our use of them.

The Hand delineates the ways in which our hands have shaped our development--cognitive, emotional, linguistic, and psychological--in light of the most recent research being done in anthropology, neuroscience, linguistics, and psychology. How did structural changes in the hand prepare human ancestors for increased use of tools and for our own remarkable ability to design and manufacture them? Is human language rooted in speech, or are its deepest roots to be found in the gestures that made communal hunting and manufacture possible? Is early childhood experience in reaching and grasping the secret of the human brain's unique capacity to redefine intelligence with each new generation in every culture and society?

Frank Wilson's inquiry incorporates the experiences and insights of jugglers, surgeons, musicians, puppeteers, and car mechanics. His fascinating book illuminates how our hands influence learning and how we, in turn, use our hands to leave our personal stamp on the world.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Frank R. Wilson is a neurologist and the medical director of the Peter F. Ostwald Health Program for Performing Artists at the University of California School of Medicine, San Francisco. He is a graduate of Columbia College in New York City and of the University of California School of Medicine in San Francisco. The author of Tone Deaf and All Thumbs?, he lives with his wife, Patricia, in Danville, California. He can be reached by e-mail at handoc@well.com.

From the Back Cover

"The remarkable human hand has clearly played a fundamental role in our evolution, but it is rarely accorded the prominence it deserves in discussion of the human fossil record. In this lively and highly personal account Frank Wilson engagingly redresses the balance, restoring the hand and the structures that move it to the very center of the story, and relating them ingeniously to the cognitive uniqueness that we normally consider the hallmarks of humanity. A book for everyone curious about how we became what we are."

--Ian Tattersall, author of Becoming Human

"This is a book to savor as one does a gourmet meal, not as one wolfs an oyster. It is about more than hand and brain and language and culture; it is about people, fascinating, remarkable, outstanding people, all of them individuals who have found their role in life and love it and are successful at it, and owe it all to their use of their hands and brains and bodies. Best of all, perhaps, is that Wilson sees this as able to change the world-simply by realizing that underlying language, intellect, and intelligence is the understanding that comes from hands-on experience. It is my candidate for best book of the decade."

--William Stokoe, author of Simultaneous Communication, Asl, and Other Classroom Communication Modes

From the Inside Flap

man hand is so beautifully formed, its actions are so powerful, so free and yet so delicate that there is no thought of its complexity as an instrument; we use it as we draw our breath, unconsciously." With these words written in 1833, Sir Charles Bell expressed the central theme of some of the most far-reaching and exciting research being done in science today. For humans, the lifelong apprenticeship with the hand begins at birth. We are guided by our hands, and we are indelibly shaped by the knowledge that comes to us through our use of them.

The Hand delineates the ways in which our hands have shaped our development--cognitive, emotional, linguistic, and psychological--in light of the most recent research being done in anthropology, neuroscience, linguistics, and psychology. How did structural changes in the hand prepare human ancestors for increased use of tools and for our own remarkable ability to design and manufacture them? Is human language rooted in speech, or

Reviews

An extended synthesizing meditation on the human hand from Wilson (Tone Deaf and All Thumbs?, 1986). Green-thumbed, butter-fingered, hamfistedwhatever its talents (or lack thereof), the hand is more than a metaphor of humanness; it is, in Wilsons estimation, a focal point in the fulfillment of life, in our cognitive architecture; it represents our chance to put our stamp on the world. Though there are no crashing breakthroughs into the ultimate mystery of the hand, into the exact pathways by which it affects our growth and thoughts and creativity, Wilson does show how very special the hand is through a summationa quite literate oneof the theories of anatomists, philosophers, psychologists, linguists, anthropologists, and, of course, since they share his calling, neurologists, about its physiological evolution and cognitive linkages. He details where the hand came from and its repertoire of movements; its role in symbolic thought; a fascinating tour of the mechanics of arm/hand movement, complete with experiments for readers to perform that are highly enlightening; how the non-dominant hand frames, spatializes, the dominant hand's activity. He is equally at ease discussing the work of Chomsky, the sublime talents of puppeteers, and the juggler's visual jokery; he draws out the common thread among legerdemain, prestidigitation, and delicate surgery; he is particularly captivated by the knowing hand, one that is guided to automobile tinkering or playing the guitar or rock climbing at an early age. And he is frustrated with our inability to ``apply systematically to individuals what we know from biology about the nature of human learning.'' ``Any theory of human intelligence which ignores the interdependence of hand and brain function . . . is grossly misleading and sterile.'' The point is well made by Wilson in this ranging, anecdote-strewn, and engaging study. (b&w illustrations) -- Copyright ©1998, Kirkus Associates, LP. All rights reserved.

If not exactly "a limitless study," it is a vast undertaking. The author duly acknowledges that each chapter raises more questions than it answers. But this, incidentally, ought to be reckoned a mark of the book's excellence, for it makes the reader aware of the wonder in trivial, everyday acts, and reveals the complexity behind the simplest manipulation.

Neurologist Wilson (Tone Deaf and All Thumbs?) gathers arguments from anthropology, psychology and medicine, along with the personal stories of musicians, backhoe operators, puppeteers and prestidigitators, to demonstrate the centrality to intelligence of our human hand. His account of the coevolution of hand and brain through our primate ancestors is fascinating, and the science he sites is rigorous and profound. The insights along the way are startling to the layperson even if old news to savants. For example, the size of a primate's neocortex is proportionate to the size of its maximum stable social group (our own being about 150). The emphasis throughout is on "the interaction of the biologic and social processes," as, for example, an artist, from early childhood, finds her way toward her instrument, and also as the species itself evolves over millennia, starting, as Darwin observed, with the freeing of the upper limbs by our descent from the trees. Out of the analysis of intelligence as fundamentally somatic there emerges a critique of educational theory. Wilson is a passionate advocate of process-centered teaching with attention to individual intelligences. Despite absorbing material and an ultimately cogent and important argument, his book dwells too long on inessential details of the case histories, and it sometimes loses steam in scholarly discourse; also, the organization into short, pithy chapters obscures the structure of the whole. Thus, although their work is rewarded, readers have to labor a bit too hard to tie the argument together. B&w illustrations throughout.

Copyright 1998 Reed Business Information, Inc.

A neurologist maintains that the hand is equal to the brain in understanding human evolution and intelligence. The cephalocentric view, as Wilson technically labels the obsession with the noggin, overshadows the hand's role in mediating the physical world for the brain. His presentation of the pro-hand position can be dauntingly specialized, as in his description of digital anatomy, but Wilson's material comes together in his profiles of people whose hands are crucial in their careers. In his interviews with a car mechanic, marionette master, juggler, surgeon, magician, guitarist, and others, Wilson effects his book's goal of discovering the "hidden physical roots . . . of passionate and creative work." The interviewees recall when they realized their special skills and the dedication necessary to achieving their manual adroitness. Outside of such tangible testimonials, Wilson discusses how researchers think hands evolved in the successive species of the hominid line or hands' speculated role in the emergence of language. A palm-opening discussion of an appendage most take for granted. Gilbert Taylor

Why human beings developed such large brains is an open question in evolution. Neurologist Wilson argues that oversized brains were advantageous in order to control the hand, which in turn makes it possible to control the external environment. Drawing upon biology, linguistics, psychology, anthropology, and other fields, he exhibits a firm "grasp" of diverse subjects.

Copyright 1999 Reed Business Information, Inc.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Prologue

Early this morning, even before you were out of bed, your hands and arms came to life, goading your weak and helpless body into the new day. Perhaps your day began with a lunge at the snooze bar on the bedside radio, or a roundhouse swing at the alarm clock. As the shock of coming awake subsided, you probably flapped the numb, tingling arm you had been sleeping on, scratched yourself, and maybe even rubbed or hugged someone next to you.

After tugging at the covers and sheets and rolling yourself into a more comfortable position, you realized that you really did have to get out of bed. Next came the whole circus routine of noisy bathroom antics: the twisting of faucet handles, opening and closing of cabinet and shower doors, putting the toilet seat back where it belongs. There were slippery things to play with: soap, brushes, tubes, and little jars with caps and lids to twist or flip open. If you shaved, there was a razor to steer around the nose and over the chin; if you put on makeup, there were pencils, brushes, and tubes to bring color to eyelids, cheeks, and lips.

Each morning begins with a ritual dash through our own private obstacle course--objects to be opened or closed, lifted or pushed, twisted or turned, pulled, twiddled, or tied, and some sort of breakfast to be peeled or unwrapped, toasted, brewed, boiled, or fried. The hands move so ably over this terrain that we think nothing of the accomplishment. Whatever your own particular early-morning routine happens to be, it is nothing short of a virtuoso display of highly choreographed manual skill.

Where would we be without our hands? Our lives are so full of commonplace experience in which the hands are so skillfully and silently involved that we rarely consider how dependent upon them we actually are. We notice our hands when we are washing them, when our fingernails need to be trimmed, or when little brown spots and wrinkles crop up and begin to annoy us. We also pay attention to a hand that hurts or has been injured.

The book you are holding is a meditation on the human hand, born of nearly two decades of personal and professional experiences that caused me to want to know more about the hand. Among these, two had the greatest impact: first, as an adult musical novice, I tried to learn how to play the piano; second, as an experienced neurologist, I began to see patients who were having difficulty using their hands. Each experience afforded its own indelible lessons; each spawned its own progeny of questions.

Like most people, I have spent the better part of my life oblivious to the workings of my own hands. My first extended attempt to master a specific manual skill for its own sake took place at the piano. I was in my early forties at the time and in my dual role as parent and neurologist had become enchanted by the pianistic flights of my twelve-year-old daughter, Suzanna. "How does she make her fingers go so fast?" was the question that occurred to me when I interrupted my listening long enough to watch her play. I read everything I could about the subject and finally realized I would never find the answer until I took myself to the piano to find out.

As a beginning student I imagined that music learning would go just as it is depicted by music teachers: begin with simple pieces, learn the names of the notes, practice scales and exercises, memorize, play in student recitals, then move on (shakily or steadily) to more and more difficult music. But over the course of five years of study my personal experience deviated further and further from this itinerary. It was not that I was fast or slow, musical or unmusical; at various times I was each of those. Despite the guidance of a seasoned teacher armed with the highly polished canons of music pedagogy, the whole enterprise was rife with unexpected turns, detours, and diversions. Inside me, it seems, there was already a plan for being a musician--a modest one, but a plan nonetheless: the protocols of music had simply set the specific cognitive, motor, emotional, and social terms according to which hand and finger movements that were initially unsure and clumsy would gradually become more accurate and fluent. As I hope to demonstrate--even to the satisfaction of music teachers--I might as easily have been in a woodcarving class, or learning how to arrange flowers or build racing-car engines.

After several years of piano study I began to see musicians as patients. Most came expecting that a doctor with musical training would better understand their physical problems than one without such experience. Later, the "hand cases" also came from restaurants, banks, police stations, dental offices, machine shops, beauty parlors, hospitals, ranches. All came for the same simple reason: they could not do their jobs without a working pair of hands.

A major turning point in my thinking about the hand came as the result of a presentation I made to a group of musicians about a particularly difficult and puzzling problem called musician's cramp. I had brought along a video clip to show during the talk. It was a brief clinical-musical medley of hands that had either been injured or had mysteriously lost their former skill; formerly graceful, lithe, dazzlingly fast hands could barely limp through the notes they sought to draw out of pianos, guitars, flutes, and violins. Just a few minutes after the film began, a guitarist in the audience fainted. I was amazed. This was not the sort of grotesque display one sometimes sees in medical movies; these were just musicians unable to play their instruments. When the same thing happened at subsequent presentations--a second and then a third time--I was genuinely puzzled. I decided I must have missed subtleties or hidden meaning in these films apparent only to very few viewers. It was not until much later that I came to understand the real message these fainting musicians were expressing.

I now understand that I had failed to appreciate how the commitment to a career in music differs from even the most serious amateur interest. Although I had worked very hard as a beginning piano student, took the work seriously and spent a great deal of time at it, it was not my life. Consequently I did not anticipate the profound empathy for the injured musicians that would be felt by some viewers of these films. Moreover--and this is a lesson I learned, one person at a time, as I conducted interviews with nonmusicians for this book--when personal desire prompts anyone to learn to do something well with the hands, an extremely complicated process is initiated that endows the work with a powerful emotional charge. People are changed, significantly and irreversibly it seems, when movement, thought, and feeling fuse during the active, long-term pursuit of personal goals.

Serious musicians are emotional about their work not simply because they are committed to it, nor because their work demands the public expression of emotion. The musicians' concern for their hands is a by-product of the intense striving through which they turn them into the essential physical instrument for realization of their own ideas or the communication of closely held feelings. The same is true of sculptors, woodcarvers, jewelers, jugglers, and surgeons when they are fully immersed in their work. It is more than simple satisfaction or contentedness: musicians, for example, love to work and are miserable when they cannot; they rarely welcome an unscheduled vacation unless it is very brief. How peculiar it is that people who normally permit themselves so little rest from an extreme and, by some standards, unrewarding discipline cannot bear to be disengaged from it. The musician in full flight is an ecstatic creature, and the same person with wings clipped is unexploded dynamite with the fuse lit. The word "passion" describes attachments that are this strong. As I came to learn how such attachments are generated, it became the mission of this book to expose the hidden physical roots of the unique human capacity for passionate and creative work. It is now abundantly clear to me that these roots are more than deep and more than merely ancient. They reach down, and backward in time, past the dawn of human history to the beginning of primate life on this planet.

Paleoanthropology--the study of ancient human origins--has until recently been better known to the public through cartoon images than through its serious work. But this seemingly dry as dust discipline is now followed by an enthralled public because of the stunning discoveries and brilliant reporting of its most prominent modern pioneers, including the Leakey family in Kenya, Donald Johanson, and, of course, Stephen Jay Gould. New information harvested from fossilized skeletal fragments millions of years old has both enlivened evolutionary theory and joined it to the developmental and behavioral sciences, linguistics, and even the neurosciences. Charles Darwin's name and his ideas are again as widely discussed and debated as they were in the middle of the last century. Indeed, the explosion of recent publications about Darwin, neo-Darwinism, universal Darwinism, and even neural Darwinism certify his genius; with the passage of time the impact of his insights and his work simply grows and grows.

Reawakened interest in Darwin finds a quiet but highly significant counterpart in a recent growing awareness of the remarkable life and work of Sir Charles Bell, a Scottish surgeon who was not only a contemporary of Darwin but one of the most respected comparative anatomists of his day. As a young boy, Bell had not only studied drawing but assisted his older brother in the teaching of anatomy. In 1806, having moved from Edinburgh to London and having become an anatomy teacher himself, he published Essays on the Anatomy of Expression in Painting, a book which was popular with both artists and surgeons and which remained in print for over forty years. Bell's work on comparative anatomy was well known to Darwin, and his Essays presaged Darwin's publication, in 1872, of The Expression of the Emo...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherPantheon

- Publication date1998

- ISBN 10 0679412492

- ISBN 13 9780679412496

- BindingHardcover

- LanguageEnglish

- Edition number1

- Number of pages397

- Rating

FREE shipping within U.S.A.

Destination, rates & speedsSearch results for The Hand: How its use shapes the brain, language, and...

The Hand: How its use shapes the brain, language, and human culture

Seller: Dream Books Co., Denver, CO, U.S.A.

Condition: good. Gently used with minimal wear on the corners and cover. A few pages may contain light highlighting or writing, but the text remains fully legible. Dust jacket may be missing, and supplemental materials like CDs or codes may not be included. May be ex-library with library markings. Ships promptly! Seller Inventory # DBV.0679412492.G

Quantity: 1 available

The Hand: How Its Use Shapes the Brain, Language, and Human Culture

Seller: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Good condition. Good dust jacket. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Seller Inventory # K11Q-01831

Quantity: 1 available

The Hand: How its use shapes the brain, language, and human culture

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.73. Seller Inventory # G0679412492I3N00

Quantity: 1 available

The Hand: How its use shapes the brain, language, and human culture

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.73. Seller Inventory # G0679412492I3N00

Quantity: 1 available

The Hand: How its use shapes the brain, language, and human culture

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.73. Seller Inventory # G0679412492I4N00

Quantity: 1 available

The Hand: How its use shapes the brain, language, and human culture

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Fair. No Jacket. Readable copy. Pages may have considerable notes/highlighting. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.73. Seller Inventory # G0679412492I5N00

Quantity: 1 available

The Hand: How its use shapes the brain, language, and human culture

Seller: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: As New. No Jacket. Pages are clean and are not marred by notes or folds of any kind. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.73. Seller Inventory # G0679412492I2N00

Quantity: 1 available

The Hand: How its use shapes the brain, language, and human culture

Seller: Goodwill Books, Hillsboro, OR, U.S.A.

Condition: Acceptable. Fairly worn, but readable and intact. If applicable: Dust jacket, disc or access code may not be included. Seller Inventory # 3IIT03005OEJ_ns

Quantity: 1 available

The Hand: How its use shapes the brain, language, and human culture

Seller: Bay State Book Company, North Smithfield, RI, U.S.A.

Condition: good. The book is in good condition with all pages and cover intact, including the dust jacket if originally issued. The spine may show light wear. Pages may contain some notes or highlighting, and there might be a "From the library of" label. Boxed set packaging, shrink wrap, or included media like CDs may be missing. Seller Inventory # BSM.L3DR

Quantity: 1 available

The Hand: How its use shapes the brain, language, and human culture

Seller: Bay State Book Company, North Smithfield, RI, U.S.A.

Condition: acceptable. The book is complete and readable, with all pages and cover intact. Dust jacket, shrink wrap, or boxed set case may be missing. Pages may have light notes, highlighting, or minor water exposure, but nothing that affects readability. May be an ex-library copy and could include library markings or stickers. Seller Inventory # BSM.MJJE

Quantity: 1 available