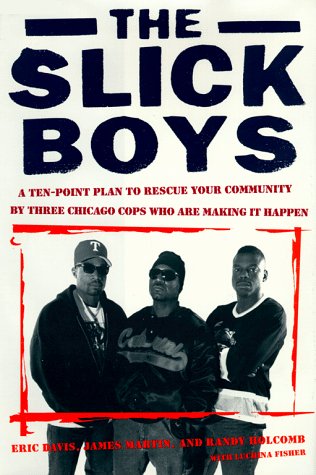

The Slick Boys: A Ten Point Plan To Rescue Your Community By Three Chicago Cops Who Are Making I - Hardcover

Synopsis

Three undercover cops bring a message of hope to the Chicago projects they patrol, demonstrated in this series of life lessons

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Eric Davis, James Martin and Randy Holcomb grew up in the housing projects of Chicago and later became police officers. Luchina Fisher, who writes for People magazine, is the winner of Chicago's Peter Lisagor Award for Excellence in Magazine Reporting. All four live in Chicago.

Reviews

In 1990, Davis, Martin and Holcomb, plainclothes cops in Chicago's crime-ridden housing projects, formed a rap music group, the Slick Boys (slang for "undercover cops"). Rapping and telling their personal stories of survival?all three grew up black and poor in the projects?the trio have spread their anti-gang, anti-drug message in performances at schools, prisons, drug rehabilitation clinics and juvenile detention centers across the country. Written with People journalist Fisher, this report interweaves the Slick Boys' scorching autobiographical narratives?Davis is a former gang member; Martin's mother held up banks and served time; Holcomb was arrested by brutal racist cops who falsely accused him of armed robbery. It features a 10-point program for working with gang members and other troubled youth, organized around such precepts as "Have big expectations," "Speak the language," "Don't play to the stereotypes." In an epilogue that recounts their continuing attempts to keep a peace?however fragile?among the gangs at Cabrini-Green, the Slick Boys make clear the need for continued community effort; throughout, they profile community action and youth services programs while a 63-page appendix lists many such organizations. Their grassroots insights into violence, abuse, delinquency and addiction and their straight-shooting writing style effectively target this handbook to its intended audience. Author tour.

Copyright 1998 Reed Business Information, Inc.

it: Eric Davis, James Martin, and Randy Holcomb. They are the Slick Boys, three plainclothes cops from Chicago who grew up in notorious projects like Cabrini Green, Rockwell Gardens, and Ida B. Welts. Such addresses often prove fatal to young black men in the city of big shoulders, but these three, friends since childhood, formed a rap group whose songs celebrated survival and religion. Their music gained popularity around the city, and all three became police officersin a town not known for its kindness to minoritiesand continue to visit the city's project to spread their message. Their grim life stories, which open the book, manage to avoid treacly sentiment. Their families share common tales of death, abandonment, and addiction, but these woes only inspire them to help others. In this book, the three introduce a simple guide for cities to adopt in order to arrest violence at its root, with police officers used as a bridge between a civil society and communities at risk. Written with the help of People magazine staffer Luchina Fisher, the language in the book is fairly straightforward and slangy throughout, but the ideas are deceptively simple. The authors rules are refreshingly phrased: ``Lead by Example'' and ``Be a Ray of Hope'' sound like snake-oil clichs, but here these notions come alive with ideas about good parenting, good citizenship, and optimism. Their enthusiasm is infectious. While they don't offer solutions to huge issues like racism and poverty, the Slick Boys present an attitude that is both reasonable (``Don't play to the stereotypes'') and intelligent (``You're a slave if you're not educated''). A wise and believable mandate for surviving an inner-city childhood. -- Copyright ©1998, Kirkus Associates, LP. All rights reserved.

Three undercover Chicago police officers outline ways to wrest community control from gangbangers and hoodlums and return it to the law-abiding families that often live in fear in those communities. Their jobs place them close to the violence of Chicago's worst neighborhoods, including some of the most notorious housing projects in the U.S. In the course of their work, the authors picked up the street name "Slick Boys," slang for plainclothes cops. The three developed a rapport with community residents and started a rap group that preaches community empowerment. The ten-point guidelines they offer are fairly simple: serve and protect the neighborhoods, speak the language of the community, give something back to the community, encourage young people, and lead by example. By far the most fascinating parts of the book relate the personal histories of the three policemen, themselves former gang members or troubled youths who grew up in neighborhoods as rough as those they now patrol. Vanessa Bush

Any ray of hope in this period of out-of-control youth is welcome. Three Chicago cops known as the rap group The Slick Boys (street slang for plainclothes policemen) provide more than just a ray. Their new book outlines their ten principles of change to rescue embattled communities. The rapper-cops, each a success story from Chicago's toughest projects, have walked the walk and talked the talk. Sharing their personal gang stories, they recall how they kept from becoming another inner-city statistic. Now committed to saving as many kids as they can, they formed the rap group in 1990 to take their message to both large and small communities and have appeared on Oprah and Turning Point. What comes across best in this very readable and interesting book is that these guys know how difficult these problems are to solve; they don't expect miracles and don't offer platitudes. For popular sociology collections.?Sandra Isaacson, U.S. EPA Region VII Lib., Kansas City, MO

Copyright 1998 Reed Business Information, Inc.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Chapter 1: Serve and Protect Your Brothers and Sisters

When I die and people ask, "What kind of policeman was he?" I want them to say, "He made a difference in my life."

-James Martin

The "Village," on Chicago's West Side, was literally one of the city's darkest projects. There were no street lamps, and gang members had removed nearly all the lightbulbs in the building lobbies. It was summer of 1989 and a Friday night, too. With each tick of the clock, the place got a little warmer, the music a little louder, and the boys a little rowdier. By nine, the buildings were pitch-black but the sounds pouring out of the darkness signaled a party in progress.

The Village was a conglomeration of the Adams, Brooks, Loomis Court, and Abbot developments, also known as ABLA. It had a booming drug business, mostly because there were very few shootings. It was nothing to see fifteen or twenty dealers working a shift. That Friday night, they'd set up a card table just outside the building and people were lining up like customers at a fast-food restaurant.

Being a tactical officer in the Chicago Police Department's Public Housing unit meant responding to trouble wherever it broke out among the city's nineteen project developments. Randy's beat was Rockwell Gardens then, while James and I, partners since 1988, worked primarily in Cabrini-Green and ABLA. Another housing officer named Julius had accompanied me and Jimmy to ABLA that night to check out the situation.

Immediately, I spotted a man in a jacket running from the building. Wearing a jacket in summer is a dead giveaway that someone is packing something, usually drugs or a weapon. This guy was carrying both.

He was about 240 pounds, most of it muscle. The dude was bigger than me and taller than Jimmy. When we tried to handcuff him behind his back, he wrestled free and started to fight us.

Meanwhile, a mob of about fifty people had gathered outside. Julius was on crowd control and was getting jittery. Suddenly, some young dude jumped out of the crowd, pulled a gun from the dealer's discarded jacket, and ran inside the building. But we couldn't chase after him -- we were still trying to handcuff the dealer. We had to subdue him before things turned ugly. Finally, we succeeded, but as we started walking him to the car, someone yelled, "Y'all ain't taking him nowhere."

"Call a 10-1 for officer assistance," I told Julius. "We got trouble."

My mind was racing. We got the guy raw. He's caught. So why were fifteen or twenty of his buddies circling us? This dude had to be the building's drug supplier. Then Jimmy and Julius dropped the prisoner, and we pulled out our guns and aimed them at the crowd. They responded by reaching under their jackets for their own weapons. "We're fucking y'all up," they shouted.

Now I had vowed to myself while I was at the Police Academy that no matter what, I was not going to die doing this job. I would use the common sense I got growing up on the streets to make the right decisions. I didn't want to have to shoot one of these fools. But just taking off was out of the question. There was no way we were going to turn ABLA over to these guys to sell drugs. We had something to prove, especially to the decent people who lived here.

"Step away," I told the mob. "We're the police. We're just doing our job." But nobody moved. These guys were juiced up, chanting "Fuck the police. Fuck the police."

We had to get their attention. Jimmy, who's got the biggest mouth of the three of us, shouted, "Hey, listen up! We're shooting women and babies first. We will not be the only ones dying out here."

Deep down, we were all pretty scared. But if those boys had known how scared we were, they would have killed us on the spot. The fact that we didn't act frightened made them hesitate. The women and children, who had been on the periphery of the mob, started backing away.

Suddenly, a squad car drove up the fire lane, scattering the crowd. Then we heard a loud boom! Somebody was shooting at us from the building.

In the confusion, Jimmy ran behind in abandoned Toyota Corolla, which had been left in the middle of the playground. Julius and I hit the ground. Boom! The dude had fired again. Boom! Julius screamed, I'm hit, I'm hit," and his gun flew into the air. I went for it while Jimmy grabbed Julius and pulled him behind the car. When he shined his flashlight on Julius's head, he started to laugh. "Motherfucker, you ain't bleeding," I heard Jimmy say. "That's sweat." Julius had a huge knot on his forehead. Apparently, the bullet had struck the concrete, and a fragment had ricocheted and popped him on the head. Julius was going to be okay. At least for now.

I made another radio call: "Squad 10-1. Emergency. We're pinned down. We're afraid the building behind us will start shooting." We knew that if that happened, we were fucked, because we would be in their crossfire. The dispatcher asked if we wanted the war wagon, the police mobile sniper unit. "Hell, yes," I said. "Send everything. They're shooting at us."

We figured the shooter had to be the same guy who'd snatched the drug dealer's gun, but we couldn't keep our heads up long enough to see anything except the muzzle flash when he fired. Those shots were coining every few minutes, and they sounded like they were being blasted from a cannon. Even so, we couldn't resist shining out flashlights at the building just to let him know we weren't dead yet.

The two white guys from the squad car scrambled next to us. Now there were five grown men trapped behind the little Toyota. "Cops can't carry Glocks," Jimmy said, looking at the type of gun they had in their hands. "Where do you guys work?"

"The University of Illinois," came the response.

"What the fuck you doing back here?" I asked.

"You called a 10-1," they said. "We came to help you."

Jimmy just shook his head. They were crazy, but we had to give them credit: at least they were here. We had seen only one Chicago police car pass by, and it was headed in the opposite direction.

After about thirty minutes, we figured no one else was going to show, so we decided to make a break for the fire station next to the shooter's building. "On the count of three," I said, "spread out and run your ass off." I couldn't even tell if the guy was still shooting -- I was too busy running and praying I wouldn't get hit. Every one of us made it to the fire station uninjured. When my sergeant said we were lucky, I told him luck, hell -- we were blessed by God.

Afterward, the commander on the scene led a team into the building and caught the sniper. He was a seventeen-year-old kid who worked for the dealer. Even though he had tried to take the lives of five officers, the judge gave him only two years for aggravated assault.

Julius got three days off for stress because he had been in a shooting just a month before. He transferred out of the unit later that summer. Jimmy and I were back at work the next day.

In fact, Jimmy and I worked ABLA every day for the next year. I think that intimidated the drug dealers more than anything else. They had to be thinking, "We threatened them -- we shot at them -- and those fools came back."

And we kept coming back. Whether it was ABLA, Cabrini-Green, or Rockwell Gardens, Jimmy, Randy, and I were always there. That was something new to the people in those neighhorhoods. They weren't used to seeing guys who wanted to be there, who weren't saying, "I don't live here, so I don't care." When the decent folks saw that we were ready to help them and take on the bad guys, they started to believe that someone out there, that cops, truly cared about their community. The police motto, "To Serve and Protect," took on a whole new -- and for the first time, real -- meaning for them. They eagerly took us in, a

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

Search results for The Slick Boys: A Ten Point Plan To Rescue Your Community...

The Slick Boys: A Ten Point Plan To Rescue Your Community By Three Chicago Cops Who Are Making I

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Davis, Eric (illustrator). Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G068483300XI3N00

The Slick Boys: A Ten Point Plan To Rescue Your Community By Three Chicago Cops Who Are Making I

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Davis, Eric (illustrator). Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G068483300XI3N10

The Slick Boys: A Ten Point Plan To Rescue Your Community By Three Chicago Cops Who Are Making I

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. Davis, Eric (illustrator). May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G068483300XI4N00

The Slick Boys: A Ten Point Plan To Rescue Your Community By Three Chicago Cops Who Are Making I

Seller: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Davis, Eric (illustrator). Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00095678690

The Slick Boys: A Ten Point Plan To Rescue Your Community By Three Chicago Cops Who Are Making I

Seller: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Davis, Eric (illustrator). Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00097662203

The Slick Boys : A Ten Point Plan to Rescue Your Community by Three Chicago Cops Who Are Making It Happen

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Davis, Eric (illustrator). Former library copy. Pages intact with minimal writing/highlighting. The binding may be loose and creased. Dust jackets/supplements are not included. Includes library markings. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Seller Inventory # GRP78756515

The Slick Boys : A Ten Point Plan to Rescue Your Community by Three Chicago Cops Who Are Making It Happen

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Davis, Eric (illustrator). Pages intact with possible writing/highlighting. Binding strong with minor wear. Dust jackets/supplements may not be included. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Seller Inventory # 45240151-6

The Slick Boys : A Ten Point Plan to Rescue Your Community by Three Chicago Cops Who Are Making It Happen

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Davis, Eric (illustrator). Former library copy. Pages intact with possible writing/highlighting. Binding strong with minor wear. Dust jackets/supplements may not be included. Includes library markings. Stock photo provided. Product includes identifying sticker. Better World Books: Buy Books. Do Good. Seller Inventory # 15162910-6

The Slick Boys: A Ten Point Plan To Rescue Your Community By Three Chicago Cops Who Are Making I

Seller: Midtown Scholar Bookstore, Harrisburg, PA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. Davis, Eric (illustrator). some shelfwear but still NICE! - may have remainder mark or previous owner's name Standard-sized. Seller Inventory # 068483300X-02

The Slick Boys: A Ten Point Plan To Rescue Your Community By Three Chicago Cops Who Are Making I

Seller: HPB-Ruby, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Davis, Eric (illustrator). Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Seller Inventory # S_450942465