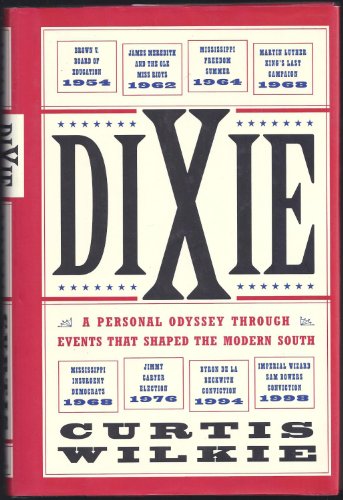

Items related to Dixie: A Personal Odyssey Through Events That Shaped...

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

"We all knew Beckwiths"

The voice sounded faintly menacing, even though he spoke by telephone from hundreds of miles away.

.

At the beginning of our conversation, he used an old Southern pronunciation that fell just short of insult -- "nigras" -- but within a couple of minutes his manner degenerated. As he talked, the old man became more exercised, and his reedy whine bristled with malevolence. "Niggers," he told me, "are descendants of the mud people," unworthy of respect. Or life, for that matter.

Then he began ranting about "Babylonian Talmudists."

"Excuse me?"

"The Babylonian Talmudists. Don't you know what a Talmudist is?"

"I think I just figured it out."

"Babylonian Talmudists are a set of dogs," he explained. "If you read in the King James Version of the Bible, you'll see that a dog is a male whore. And God says kill them."

Racial mixing, he continued, "is a capital crime, like murder is a capital crime. But the Bible doesn't say, 'Thou shalt not kill.' It says, 'Thou shalt do no murder.'"

As he spoke, I took notes furiously, because the commentary was coming from Byron De La Beckwith, soon to be standing trial again for the murder of Medgar Evers, once the most prominent black man in Mississippi. Our talk took place in January 1994, more than thirty years after Evers had been shot in the back in the driveway of his home in Jackson. In connection with an article I was writing about the coming trial, I had called Beckwith at his home in Tennessee, where he had been living, free on bond, unrepentant and flying the Confederate battle flag from his porch. In the background, I heard his wife, Thelma, imploring him not to talk with me. But after Beckwith had determined that I had been born white and raised a Christian, he had agreed to an interview. Perhaps my own Southern accent had beguiled him, though I suspect he had simply seized on what would be one of his last opportunities to expound publicly on his racial theories.

By this time, Beckwith was seventy-three years old, cornered, yet still defiant. An erstwhile fertilizer salesman, he reveled in his reputation as an unconvicted assassin, a champion of white supremacy who had exterminated an upstart leader of the "mud people." After his first two trials had ended in hung juries, he had run for lieutenant governor of Mississippi in 1967, assuring his campaign audiences that he was a "straight shooter." He said it with a grin. But even then, he was becoming an embarrassment in a state worn down by the violence of the old guard. Beckwith finished fifth in a field of six candidates, though in losing, he won thirty-four thousand votes -- sobering to think about.

Six years later, New Orleans authorities -- acting on a tip -- arrested Beckwith as he drove into the city. In his car they found a live time bomb and a map to the home of the regional director of the Anti-Defamation League of B'Nai B'rith. When a five-member jury found him guilty of participating in the plot against the Jewish leader, Beckwith declared that he had been convicted by "five nigger bitches." He served three years in the Louisiana State Penitentiary in Angola, but after the small size of the state jury was ruled unconstitutional, Beckwith had the conviction expunged from his record.

Now the Evers murder case was being resurrected, and Beckwith seemed pleased by his new notoriety. He told me he was "full of enthusiasm and adventure. I'm proud of my enemies. They're every color but white, every creed but Christian."

He alluded to his family's status in bygone days in Greenwood, when the Beckwiths had lived in a big house and circulated with those of importance in the Mississippi Delta. All that had faded; his relatives were dead, their fortune spent, their mansion in ruins. Nevertheless, Beckwith considered himself high-class, and he told me, "Country-club Mississippi is tired of this crap the Jews, niggers, and Orientals are stirring up."

My knowledge of "country-club Mississippi" lay on a par with my understanding of the Sorrowful Mysteries of the Roman Catholic Church, yet I had to suppress a snort at Beckwith's assertion. Country clubs might accept a WASP leper before welcoming Jews, blacks, and Americans of Asian descent, but I knew Beckwith had transmogrified into an even greater pariah. Despite his family pedigree, Beckwith represented a virulent element that had ultimately proved counterproductive to the Southern way of life.

For a few years in the early 1960s, it seemed that wily attorneys and buttoned-down movers and shakers in the white communities had found methods to delay integration indefinitely. They invoked states' rights and the doctrine of interposition, plotting their strategy in the backrooms of law offices rather than in clandestine meetings in piney woods. Throughout my boyhood, which coincided with the Brown v. Board of Education decision, the segregationists' plans succeeded.

Then, men lacking any subtlety, fanatics such as Beckwith, Bull Connor, the killers in Neshoba County, the bombers of Birmingham, as well as an array of reactionary governors -- Orval Faubus of Arkansas, Ross Barnett of Mississippi, George Wallace of Alabama, and Lester Maddox of Georgia -- created such a picture of hate and discrimination that the nation, and much of the South, finally began to say, Enough.

Because the segregationists' war had inflicted so much suffering on the region, I felt sure that not even "Kiwanis Club Mississippi" would want to sell Beckwith a ticket to a pancake breakfast.

Yet in some venues, I knew that Beckwith and his ilk continued to symbolize the South, and after we finished our talk, I was left with a question -- not for the first time -- of who really personifies the South.

There is no simple answer. The Southerner is an imperfect, conflicted character, not easily pigeonholed -- though a stereotype invariably develops when the South attracts national attention. We have been stamped as curious people, with wits as slow as our speech and the odor of a segregationist heritage sticking to our clothes like stale tobacco smoke. For most of the twentieth century, we occupied a rural and poor society; it seemed as if our poverty served as Old Testament punishment for our racial codes.

We are reputed to be gothic in our behavior. Our own novelists and playwrights -- recognizing the value of baroque characters -- have helped perpetuate the mythic Southerner as someone a bit weird. James Dickey, a certifiable son of the South, assembled a cast of backwoods pig-fuckers for Deliverance, while Flannery O'Connor, a Georgian, created the crazy Holy Roller Hazel Motes. William Faulkner had his Popeye, who favored a corncob as his sexual tool, and Erskine Caldwell built his books, which sold more than 80 million copies, around foolish cracker families.

In his popular 1998 novel, A Man in Full, Tom Wolfe, a native Virginian, came up with a modern version of Tennessee Williams's Big Daddy. Wolfe's character, Charlie Croker, was a onetime football hero at Georgia Tech who assured his rise from the gnat-infested bogs of south Georgia by "marrying up." Although Croker became a hard-charging Atlanta developer, he kept his uncouth ways. When Croker spoke, it was as though his words were strained through a portion of grits. ("I want'chall to know that this turtle soup comes from turtles rat'cheer at Turpmtine. Uncle Bud caught every one uv'em...") Like other pillars of Wolfe's Atlanta, Croker was happy to set his bigotry aside long enough to sit at the business table with a black man, but he didn't want his daughter to marry one.

Despite the great contributions that Southern blacks have made to our culture, the prototypical Southerner has always been a white male, and usually one with a white sheet in his background. The most messianic

man of my lifetime, Martin Luther King Jr., lived and died in the South, yet one no more thinks of him as Southern than one considers the whites of Zimbabwe as African. Southern cult figures -- Huey P. Long, George Wallace, Billy Graham, Bear Bryant, Elvis -- have invariably been eccentric white men.

In a scene from Faulkner, a young man from Yoknapatawpha County, Quentin Compson, is asked by his Canadian roommate at Harvard to explain the South: "Tell me about the South. What's it like there? What do they do there? Why do they live there? Why do they live at all?" Compson kills himself before satisfactorily answering the question, but God knows Faulkner took plenty of swipes at the South over the years. In Absalom, Absalom, he called our homeland a "deep South dead since 1865 and peopled with garrulous outraged baffled ghosts." I like that description, because we deliberately set ourselves apart from the rest of America during the Civil War and continue, to this day, to live as spiritual citizens of a nation that existed for only four years in another century. We have defied assimilation -- not so much out of an allegiance to the principles of the Confederacy as to a stubborn aversion to our conquerors.

Across the South, outward change has been profound. My generation experienced more disruption in our social order than any other demographic group in America. In a short span, we moved from enforcing segregation to accepting integration, from economic hardship to prosperity. We saw our politics turned on its head. Yet in the interior of our souls, I believe the Southerner remains unchanged, yoked to our history as surely as Quentin Compson one hundred years ago.

Pride may be one of the seven deadly sins, but I believe it is one of our finer characteristics. Sometimes we confuse pride with honor, but most Southerners are proud of the quirks that distinguish us from Middle America. We look upon the land mass below Richmond as a preserve for our customs and consider our difference our glory.

In the last half of the twentieth century, the country was homogenized by television, jet travel, and the Internet. Yet we maintained our own culture, our accent, our cuisine, our music, as if by giving them up we would finally admit defeat.

Rather than knuckle under to American conventions, we actually intensified our regional eccentricities. Like other down-and-out people, living in shtetlach beyond the Pale or in poor villages in Ireland, we cultivated a sense of humor that fed the stereotype yet served as something of a defense mechanism. Southern humorists, performing as professional rednecks, have thrived for decades as masters of self-deprecation. We would rather laugh at ourselves than be laughed at.

I love the South, yet for all of my own loyalty there was a lapse in my regional chauvinism. After Mississippi was plunged into a particularly hard period during the 1960s, I left my home state, overfed on the Southern experience. I felt we were digging our own grave with our racial policies. The decade had been a bad time, a period of intimidation and terror, of sorrow, guilt, and shame. Though I never renounced my roots, I was glad to escape them. I read The New Yorker and the novels of Cheever and Updike; their Eastern, urbane world sounded alluring. I particularly related to Willie Morris's autobiography, North Toward Home, in which the Mississippian wrote of turning his back "on the isolated places that nurtured and shaped him into maturity, for the sake of some convenient or fashionable 'sophistication.'" I was determined to join a band of expatriates on the East Coast, a group Morris described as "a genuine set of exiles, almost in the European sense: alienated from home yet forever drawn back to it, seeking some form of personal liberty elsewhere yet obsessed with the texture and the complexity of the place from which they had departed as few Americans from other states could ever be."

For nearly twenty-five years, I lived outside the South, but remained lashed to my home as surely as if I were a captive bound to a stake. I never lost my accent. When I opened my mouth as a reporter for the Boston Globe, those I interviewed sometimes asked, "Where in God's name are you from?" I never hesitated to say Mississippi. Never Boston or Washington or Jerusalem or any of my other harbors during that period, even though a claim on a different place might have made my passage easier.

Shortly after I arrived in the East, I visited Oscar Carr, a friend who had also fled the Mississippi Delta for Manhattan. An erudite man, Oscar was one of two brothers who had risked their place in Mississippi society by standing up for blacks. Though the Carr brothers were wealthy planters, they had sided with the underclass in a number of highly publicized fights for antipoverty funds and political equity. In 1968, Oscar served as a cochairman of Robert Kennedy's presidential campaign in Mississippi. After RFK's death, Oscar moved his family to New York, where, he told me with a laugh, he intended "to do the Lord's work -- officially" at the national headquarters of the Episcopal Church. After dinner at the Carrs' apartment near Central Park, Oscar decided that I should meet Willie Morris, so we set off for one of Willie's haunts, Elaine's on the Upper East Side. We were met at the bar by the proprietor, a stout woman with a reputation for rude charming. She informed us that Willie was not there. Though Willie would apparently always be welcome, she added that "redneck assholes" (a description that may have fit me, but surely not Oscar) were not. So much for my first brush with the literary dens I had read about in The New Yorker.

As it turned out, Willie's career in New York proved as incandescent as a Roman candle, and by 1980 he had returned to Mississippi to live and write eloquently of the state's dreadful past and its happier contemporary times. Years later, I finally met him while in Jackson on assignment. As our friendship developed, he encouraged me to come home, too. A gentle man, Willie had a gift for practical jokes, preferably by phone. Among the telephone messages I got in Boston, I began to hear phony editorial requests for a profile of Leander Perez, the long-dead dictator of Plaquemines Parish below New Orleans, as well as earnest suggestions that it was time to return to the South. All from Willie.

During my years away, I found the South held no monopoly on racial or ethnic discrimination. The passions exposed during Boston's busing conflict the year I joined the Globe were as raw and unpleasant as any I ever witnessed, and the hatreds I encountered later in the Middle East made the segregationist rhetoric I had heard as a young man sound like the beatitudes.

During my trips to the South to visit family or cover stories for the Globe, I began to rediscover my home and my friends. Racial problems had not been solved, but many more people were working on them. Old pals who once waved the Confederate battle flag as if to stick a finger in the North's eye had cast the symbol aside after realizing that it grated on the sensitivities of fellow citizens who were black. White elected officials suddenly sounded far more thoughtful than the demagogues of my boyhood, and throughout the region, blacks held many leadership positions.

The South also exuded a metaphysical warmth. In contrast to Boston winters, when cold bites through several layers of clothing and darkness closes early in the afternoon, the South beckoned me with its sunlight and leisurely lifestyle.

In 1993, I finally followed Willie's advice and persuaded the Globe to let me spend that winter in New Orleans to enable me to make frequent visits to my mother, who lay slowly dying in nearby Mississippi. My editor, Matt Storin, gave the move his blessing. To most ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherScribner

- Publication date2001

- ISBN 10 0684872854

- ISBN 13 9780684872858

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages352

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.25

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Dixie: A Personal Odyssey Through Events That Shaped the Modern South

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0684872854

Dixie: A Personal Odyssey Through Events That Shaped the Modern South

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # newMercantile_0684872854

Dixie: A Personal Odyssey Through Events That Shaped the Modern South

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0684872854

Dixie: A Personal Odyssey Through Events That Shaped the Modern South

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. 1st Edition. Seller Inventory # 011695

Dixie: A Personal Odyssey Through Events That Shaped the Modern South

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0684872854

Dixie: A Personal Odyssey Through Events That Shaped the Modern South Wilkie, Curtis

Book Description #N/A. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Tub 3 Mike-008

Dixie: A Personal Odyssey Through Events That Shaped the Modern South

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0684872854

Dixie: A Personal Odyssey Through Events That Shaped the Modern South

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks178685

Dixie: A Personal Odyssey Through Events That Shaped the Modern South

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. Buy for Great customer experience. Seller Inventory # GoldenDragon0684872854

DIXIE: A PERSONAL ODYSSEY THROUG

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.27. Seller Inventory # Q-0684872854