Synopsis

In a passionate, heartfelt autobiography, the humorous, honest, and well versed baseball icon candidly exposes his small beginnings, triumphant successes, initiation into the world of management, and how he remains "real" throughout the decades of the game.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Larry Dierker has spent nearly his entire adult life with the Houston Astros in one capacity or another. He made his major league debut on his eighteenth birthday in 1964, striking out Willie Mays in his first inning of work, and is still the franchise leader in starts, complete games, innings pitched, and shutouts. From 1979 until his appointment as manager, Dierker was the club's primary color analyst on radio and television, and for several years wrote a column that appeared in the Houston Chronicle. As manager of the Astros he led Houston to four division titles in five seasons. An avid connoisseur of cigars and Hawaiian shirtwear, he lives in Houston with his wife, Judy.

Reviews

Two things set career baseballer Dierker apart: he went from broadcaster to manager with zero managing experience, and he suffered a brain seizure in the Astrodome dugout during a game. The first item gets ample coverage in the book, but surprisingly, the second does not. An accomplished major league pitcher with a no-hitter and a few all-star appearances to his credit, Dierker foreshadows his impending tragedy from the beginning, as he strikes out Willie Mays in his major league debut (also Dierker's 18th birthday), right up until the fateful day in 1999. Yet the actual event warrants barely six pages. A Hawaiian shirt-wearing party guy, Dierker clearly had no interest in writing a mawkish memoir, but the reader will nonetheless hunger for a bit more on how his horrific flirtation with death shaped his life. Dierker's prose is witty and easy-reading it is like hearing stories over a beer from the guy sitting next to you at the ballpark. But the yarns often come up short: old teammates trumpeted as "characters" come across as flat, and the book could use sharper focus: it's alternately a pitching book, a managing book, and a book about old-time baseball, when players drank beer and raised hell. After 37 years in major league baseball, Dierker undoubtedly has stories to tell, such as his teammates' first glimpse at the surreal new Astrodome in 1965. That his book isn't chock-full of them is somewhat disappointing.

Copyright 2003 Reed Business Information, Inc.

*Starred Review* Dierker, a pitcher and then radio commentator for the Houston Astros, stepped out of the announcer's booth to become the Astros' manager in 1997. He "retired" (a euphemism for fired) after the 2001 season despite four of the most successful years in team history. Baseball and the Houston Astros have been Dierker's professional adult life, but unlike many baseball lifers, he has a healthy perspective about the game and his role in it, as reflected in the title of this literate, humorous, and entertaining memoir. As he recounts his tenure as manager, he splices in anecdotes from his playing days, effectively contrasting the life of the ballplayer in both eras. In the past, most baseball careers were part of an extended adolescence--a few years in the game before moving on with real life. Today's huge salaries have changed the stakes considerably: with one good contract, the financial future of a player--and a couple generations' worth of his descendants--is assured. But much of baseball's color still comes from its eccentric characters, and Dierker profiles several of them, including Doug Rader and Casey Candaele. On a more serious note, he also discusses how he coped with the big-money world of modern baseball and how he made the day-to-day decisions with which a manager is confronted. One of the best baseball books of the spring season. Wes Lukowsky

Copyright © American Library Association. All rights reserved

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Well, I'll tell you, young fella, to be truthful and honest and frank about it, I'm eighty-three years old, which ain't bad. To be truthful and honest about it, the thing I'd like to be right now is an astronaut.

-- Casey Stengel

In September of 1996 I was suffering. I had spent a good part of the baseball season in the hospital. First it was surgery on a torn ligament in my right thumb; then it was pericarditis, an inflammation in the lining of the sac that contains the heart; then it was surgery again for a bone infection where the first surgery had been performed on my thumb. All told, I was in one ward or another for three weeks and under anesthesia four times. The last time, I left the hospital with a bottle of prednisone, a medicine so powerful that it changes your personality and makes you into a trencherman of mythic proportions. I came out of the hospital weighing 215 pounds and a month later tipped the scales at 240. What's worse, I was doing a lot of the eating in the middle of the night, interrupting my sleep. I was so hungry I couldn't make it through the night without a meal. By September, most of my health problems were under control. The only lingering reminder of my personal travails was the cast on my right hand that had forced me to keep my scorebook left-handed while broadcasting all year long. I couldn't wait for season's end, but I sure didn't want it to end in free fall.

Everyone with the Astros was suffering to some extent. The team had fallen out of the race and was in the midst of a nine-game losing streak that would give the Cardinals the Central Division title on a platter. It is so discouraging to tough it out for five months and over 125 ball games only to plummet like a stone thrown into a lake; but that's exactly what we did. I was determined to float down the Guadalupe River on an inner tube when the season ended, soaking my right hand in the cool water and enjoying a beer or two along the way, but first we had to finish the schedule and it was on the next to last road trip of the season that I uttered a line that has had a major impact on my life. It happened near the end of the losing streak, during a game with the Marlins. Florida didn't have a very good team that year but they were making us look like Little Leaguers.

We were way behind, maybe 9-2, in this particular game. Our cameras panned the dugout and it looked like a morgue. "You know what's wrong with this team, Brownie?" I asked my partner Bill Brown.

"Well, we're not hitting," he offered.

"No, it's not that," I said.

"Well then, what is it?"

"Not enough Hawaiian shirts," I said.

"Hawaiian shirts?"

"Yeah, Hawaiian shirts," I repeated. "Everyone in that dugout looks like someone in their family has died. You have to have some spirit to win games. This team looks dead. Did you ever see someone wearing a Hawaiian shirt that wasn't having a good time?"

"Well, no," he answered. "But where's yours?"

"I'll wear it tomorrow night," I said, not knowing how difficult it would be to find one, even in Miami.

The next day I canvassed the mall and came away with a shirt that had flowers on it -- not really a Hawaiian shirt, but close. I didn't tell our producer or director that I was going to wear it for fear they would insist on our normal coat and tie policy. We lost again, but the words had been spoken. We talked about Hawaiian shirts during that broadcast and the next two in Atlanta, and by the time we got back to Houston, it was general knowledge among our faithful fans.

I called my boogie-boarding brother, Rick, and asked him to send me a couple of shirts. One of them was decorated with vintage woodie station wagons from the 1940s, a popular surfer car when I was in high school. The woodies on this particular shirt had surfboards hanging out the back windows or mounted on top. I wore it to the ballpark, just for grins. About half an hour before the game, I had a devilish idea. I was working radio with play-by-play man Milo Hamilton that night and I was almost sure he didn't know that the term "woody" was current slang for an erection. When Milo was out of earshot, I told our engineer and several young interns to listen closely. "I'm going to get Milo," I said. "Just wait."

When Milo came back into the booth, I pointed to one of the woodies on the shirt and said, "Hey, Milo. You know what this is?"

"Uh, a station wagon," he ventured.

"No, this is a woodie, man. You should know that. It comes from your era. These things were the rage when I was in high school in California. They were surfer cars."

"I didn't know they called them that," he said.

We went on the air and after he got all the preliminary information out, and with plenty of time in the inning to talk, I asked, "Hey, Milo. How do you like my new Hawaiian shirt?"

"You mean the one with all the woodies on it?" He took the bait. I could imagine all the middle-aged and younger fans in our audience getting a mental image of a shirt full of hard-ons.

"Yeah," I said. "When you were a young man, did you ever have a woodie?" I hadn't planned that line. It just came out.

"Oh no," he said. "We were much too poor."

"Boy, that's really poor," I said, stifling laughter, and looking back behind me where the others in the booth were sitting. One intern bolted from the booth. I imagine he couldn't contain himself. The rest of them were giggling in silence.

The next day, word of the interchange swept through the Astrodome like a brushfire. It was especially funny because Milo is a proud man, to say the least. He is not the type of person who can admit a mistake, let alone laugh at himself. Thinking about him discussing erections on the air gave rise to convulsions of laughter as it spread from office to office throughout the building. It continued for several days and Milo never knew it. I wore the shirt and got him a few more times before the season was over.

Although we were mourning the loss of our playoff hopes, we were also obligated to finish the schedule, and in this type of situation humor helps. If the players could just share in our glee, they would be better off. But they showed no outward signs of shedding the burden of choking in the clutch.

Nobody was happier to see the season end than I was. I was in Austin the night we finished, staying with friends for a few days. The next evening, when I came in from floating on the river, there was a message to call my wife, Judy.

She told me that the president of the Astros, Tal Smith, had called and he wanted to see me in his office at ten o'clock the next morning and that it was urgent. I grudgingly drove back to Houston, wondering what could possibly be so important.

A computer-tone version of "Take Me Out to the Ballgame" announced my arrival as I walked through the glass doors of Tal Smith Enterprises. "Let's sit out here on the balcony where we can relax," Tal suggested. Seven stories below, shoppers perused the many offerings of the Galleria, as Tal came characteristically to the point. "If you had to trade Bell [Derek] or Kile [Darryl] to make budget, which one would it be?"

"Well, we all know you don't win without pitching," I replied. "But Bell is a star and he could get better. I guess I would have to let Kile go, even though I wouldn't want to." As it turned out, we did not part with either player, and Kile, not Bell, got better.

Our conversation continued along these lines. Before long, we had discussed just about every player on the team. "Sounds like you've got a pretty good grasp of where we are and where we need to go," Tal said. "Maybe you should manage the club."

"Well, I'll tell you," I said. "I've been trying to think of a way to get away from Milo, but that would be rather extreme."

Tal laughed so loud that shoppers way down below looked up to see what was happening. It was all in the spirit of kidding from my standpoint. He had another perspective.

"I've taken the liberty of ordering some sandwiches," he said. "We can have lunch here."

"Fine," I said. I looked back toward Tal's longtime secretary Judy Vieno's desk and spotted Astros general manager Gerry Hunsicker.

"Let's go in here where we have more room," Tal said. "Gerry is going to join us if you don't mind." This is when I sniffed a hidden agenda. I couldn't imagine it to be anything that was personally threatening, and I always enjoyed talking baseball with Tal and Gerry, so I said an internal "what the heck" and chomped into a turkey sandwich. As we continued the evaluation, I was asked what I would do differently if I were running the team. "Well, I'd get some left-handed hitters and some pitching depth," I replied.

After we discussed relative strengths and weaknesses and commiserated over budget constraints, Tal and Gerry came to the heart of the issue.

"What did you think about Terry's performance last year?"

I paused.

Terry Collins, the manager of the Astros, had grown unpopular with the players as most managers eventually do. I am not a big fan of his hyperkinetic style, but I regard him as a smart baseball man, an energetic worker, and a keen competitor. I knew he was on the hot seat, but I had heard that the club would not eat the last year of his contract.

"I think he does a good job," I said. "I don't always agree with him, but that's what the game is all about."

"What about the clubhouse?" I was asked. "Did you get any feedback from the players?"

"Well, I know they aren't wild about him. But they liked him just fine and he seemed like a better manager in '94," I said. "We had a better team and we were winning more then. It makes a big difference."

"They say he's lost the clubhouse."

"It's a long winter. He can get it back."

At this point I realized that I was being interviewed for the manager's job. They hadn't really said that Terry was going to be fired but that's what I heard. My head was spinning like the Wheel of Fortune, but I knew I had to stay calm. It was like being on the mound, with a thousand thoughts crossing your mind while you try to concentrate on just one or two.

"How do you feel about statistical information?" Tal asked. "Do you think you can get an edge by getting favorable match-ups?"

"Sometimes," I said. "When a guy has hit a certain pitcher, year after year or vice versa, it is worth noting. I do think, however, that managers use statistics too much. If a guy is 3-5 against a particular pitcher and another guy is 0-4 that means very little to me. The sample is too small. In that case I would favor my instincts. If the pitcher is a sinker, slider guy, I would play the guy who is the best low-ball hitter. That type of thing."

I knew Tal to be a number cruncher; he relies on statistics to present his arbitration cases. I was relieved when he said, "I agree. I think a lot of managers fail to play hunches and use their instincts."

Whew, I thought. I cleared that hurdle, still not knowing if I wanted to clear it. At this juncture, I was competing for the job and wasn't sure why except that it is my nature to try difficult things. I guess I sensed this chance might not come again.

"Any manager in today's game has all the numbers he needs," I said. "And he would be a fool not to use them. But the most important thing is the combination of players a manager has available, the way he deploys them, and the effort they give. If you don't have the horses you can forget it. If you have horses that can run together, you have to cue them up right. Get the right batting order, get them enough playing time. Then you have a chance, but only if they want to run. Let's face it, a team is only as good as it thinks it is. Confidence is critical."

At that point, I brought up the importance of pitching, citing our division championship years in the 1980s. "The most important aspect of confidence is pitching," I continued. "You simply can't win a championship without good pitching. You can make it if your fielding and hitting is only adequate, but you must have a good bench because you'll have to deal with injuries."

"What would you do about Bagwell [Jeff] and Biggio [Craig]?"

This question stunned me. "Bagwell and Biggio?" I said. "Nothing. I'd just write their names in the lineup and let them play. I can't imagine those two guys being a problem."

"You might be surprised," Tal said. "They carry a lot of weight in the clubhouse and they brought it to bear on Terry."

I thought for a moment. I had heard that Biggio and Bagwell were unhappy with Terry. "Remember the story about Joe McCarthy when he took over the Red Sox?" I said.

Tal remembered it, but I doubted that Gerry did, so I elaborated.

"When McCarthy was with the Yankees, he was a stickler for appearances. He felt that it was important for the Yankees to maintain their classy image by dressing in a suit and tie whenever they were together. When he went to Boston, the writers jumped him about his dress code. 'What are you going to do about Ted Williams?' they asked. Well, everyone knew that Williams refused to wear a tie. And McCarthy wasn't stupid. 'That's easy, boys,' he said. 'If Ted doesn't want to wear a tie, he doesn't have to. If I can't get along with a .400 hitter, I should be fired.' "

This is the way I felt about Bagwell and Biggio. I don't know how Terry got crosswise with them; they certainly didn't do anything on the field to cause him trouble -- quite the opposite. They played hard and smart; they played hurt; they played every day. I don't know what happened behind the clubhouse doors, but if I had players like that I would find a way to get along with them. Perhaps they wanted to run the team -- to dictate who played, or what the batting order should be. This type of criticism is common with star players and it could either be a problem or it could be a solution. Players like Bagwell and Biggio have a lot of good ideas. I would listen to them, and if I didn't want to use their suggestions I would tell them why. Throughout my thirty-seven years in baseball, I had heard manager after manager say that there was one set of rules, not two. But in actuality, the stars got more than their share of favors. I got the star treatment myself for a few years and I didn't believe in one set of rules. I believed in the elasticity of a few rules. Playing hard and winning is the only real answer. When you do that, nobody cares about how the rules are applied.

"Look, I'm tired of this Bagwell and Biggio shit," I said. "Bagwell and Biggio will not be a problem, believe me."

I now believe that this statement is the one that got me the job. It also proved to be false.

One more thought on Biggio and Bagwell. In the spring of 1996, it was suggested that these two fine ballplayers, who had played with uncommon valor in the Wild Card race the previous September, should be made sort-of unofficial team captains and accept a leadership role in the clubhouse. This seemed a good idea, but it didn't work out. Bagwell cares deeply about the team, but his leadership talents are mostly nonvocal. Biggio is a team guy too and he likes to talk. But he is a driven man, a perfectionist. It works well for him, but leaves him intolerant of those who are less motivated. He may make a good leader as the years soften his edge, but in 1996 he wasn't ready. I didn't expect problems with these two guys because I would not ask them to work overtime. I would not ask them to be captains. I would address team problems myself, acting as policeman if necessary. I would ask Bagwell and Biggio to do just one thing: Play.

About this time I peered through the glass door of Tal's conference room and saw our owner, Drayton McLane.

This is it. Today's the day, I thought. I wonder if they will offer it today and I will have to say yes or no. The prospects were both exciting and frightening. I thought about all the things that could go wrong. What if I got fired in an unfriendly way? If that happened, I probably couldn't get my broadcast job back. What then? I thought about Judy, my daughter Julia, and my son, Ryan. They would like it, I was pretty sure of that, but would it cut into my time with them? What time? I have been a lot like my dad, working all the time. They haven't gotten much from me anyway. Perhaps in this role my influence would be greater. Maybe they would come to the games more often and we would have things to talk about and the kids might actually listen to me. I didn't see a red flag in the family department. I guess the only thing that truly scared me was my health. With everything that had happened that summer, and the underlying possibility of anxiety, managing could take a heavy toll. What the hell, I thought. I've had enough bad health this year to last for a while. I'll just have to get into good shape, something I had planned to do anyway.

Drayton came in, smiling like a practical joker. "How are things going so far?" he quipped. "Do we have ourselves a candidate?" We all smiled and Tal said that we had covered a lot of ground. "He clearly knows this team better than anyone we could get from the outside. He seems to have a good grasp on the issues too."

I felt like a champion, which is just the way Drayton wants everyone to feel. His two favorite expressions are "Thanks for your leadership" and "Do you want to be a champion?" I was ready. I wanted to be on the team.

"So, what is your theory of leadership?" he asked.

Drayton is a motivator, a self-described cheerleader, so this was a tricky question because I knew that I couldn't do it the way he does. I would have to have my own style. I knew some of his slogans, like "A leader is a guy who will take you to a place you wouldn't go on your own." I had read some books about successful big league managers and their theories, and had seen seven of them operate firsthand. I would have to act naturally, do it my own way, take the strong steady approach. Not too much bullshit, just clear instructions and common sense. Not too high, not too low, but doggedly persistent.

"My high school coach used to say you can lead a horse to water but you can't make him drink," I said. "The first thing is to identify the ones that will drink." I tickled myself with that statement. It just sort of came out that way and when Gerry and Tal started laughing, Drayton did too.

"Seriously, if you have to make players do things, you're in trouble to begin with. You have to have players who are self-motivated. The next part is tricky; you have to make them believe you can lead them. In my case, that will be the biggest challenge. They know I played; they think I'm a good guy; but they also want to win badly, and they don't want some rookie manager who makes an ass of himself. I'll have to win their respect with my judgments and it will take time. I feel like I can accomplish this because we have good players. Winning creates the atmosphere of success and that feeling rubs off on everyone, including the manager.

"Afterward, we'll have a few drinks," I said. I couldn't resist.

We talked in this vein for another hour and everything went well. The meeting lasted so long that I had to call Judy and arrange for her to pick Ryan up from school. He is seventeen years old now and can drive, but did not get one of the few parking passes allotted to juniors. He can also walk and it is less than a mile to his school. But that's another story, which is more about his mother.

Anyway, when our meeting was finally over, I was told that Gerry would call me with the salary and the particulars later that night. He would expect my final decision and there would be a press conference tomorrow.

I went to Ryan's fall league baseball game with Judy that night and we sat in the stands and watched. We exchanged pleasantries with friends and acquaintances. I knew I was the Astros manager and so did Judy. It was our secret.

The press conference came the next day. I had so many butterflies I thought I might lift off until I realized that the weight of the world was upon me. I had some serious buyer's remorse. Had I compromised myself for the fame and fortune? I didn't need fame, would just as soon do without it, but like everyone, I could find a good use for more money. Why be so greedy? I asked myself. You don't need the money. You just want it. Is it pride that is pulling you? Or is it the affirmation that you are a real baseball expert with skills that go beyond performance?

That's it, I told myself, and that's exactly the way Judy put it when I told her. "It's about time they realized how much you know and what you can do. You deserve it," she said.

What she didn't know is that a lot of other guys deserved it more: guys who had slaved away in the minor leagues, guys who had spent years as bench coaches in the big leagues. Guys who were fully apprenticed and clearly capable and better prepared than I.

Of course, I was prepared for the Fox broadcast job that went to Giants coach Bob Brenly, who was better prepared to manage. It's a crazy world, I thought. You have to take it as it comes. Don't worry. Everything will be all right.

I was terrified.

I was teetering on the edge of anxiety before attending the press conference. I felt the tingle on every nerve ending. It had happened so fast that I had almost no time to prepare my thoughts. In the end it was like pitching on opening day. You worry yourself to death and then the game starts and you are fine.

Gerry was introduced by our PR director, Rob Matwick. He walked to the microphone in front of the little Astros theater and spoke to about fifty media representatives. "The Astros have relieved Terry Collins of his duties," he said as the murmur in the room fell to a hush, "and the next Astros manager is in this room." That was a great line. Reporters were scanning the room, but nobody guessed it. When I was brought forth, the murmur returned. There was a sense of giddiness and it spread to a shared grin. I was one of them: I had not only broadcast the games for eighteen years, I had written a weekly column for the Houston Chronicle for ten. This was either a great joke or a great story. Either way, it was more than they expected.

Tal came up and made a short speech on the reasoning of the move. Drayton told the story of our meeting and how surprised I was. Finally, I was up there holding my first press conference. It went rather well, I thought.

"Is this your dream job?"

"No, I just gave up my dream job. This will be a lot harder."

"Whatever possessed you to take it?"

"I don't know," I said. "I guess it's like someone gave me an opportunity to be an astronaut and go to the moon. At first I would think of all the excuses why I couldn't do it. I'm too tall to get into the capsule. I don't know how to fix rocket engines. I'm claustrophobic. I have a dental appointment next week. None of the excuses were any good. I realized I had a chance to do something bold and exciting. Something offered to only a select few. If it didn't kill me it would be an unforgettable experience."

"What about the downside? You know you're going to be fired?"

"Yes, I know that. But my only regret is that as a player I never made it to the World Series. Now I have a chance to go -- in uniform -- this is a pretty good ball club. In the end, the lure of the competition was too much. I said the hell with safety. Fire up the engines!"

If I hadn't taken the job, I would never have forgiven myself. I would have felt like a coward. Sure, I was scared, and I realized that I might be making a colossal mistake, but I had to do it. I just had to.

After the press conference, it came easier. The TV stations sent reporters to my house to do interviews for the six o'clock news. Ryan was jumping up and down behind me waving his hands so his friends would see him on television. That night, he had another ball game. I sat in the stands with Judy, just like before, but this time I was signing autographs and answering questions the whole time. I felt like the same guy, but people, even our friends, were treating me differently -- like a hero. I haven't even won a game, I thought. This is amazing.

It also had a dreamlike quality that made me feel uneasy. As I traveled around Houston, people recognized me more often; they usually called me Coach. This appellation bothers most baseball managers. It is an affront because the coaches work for the manager in professional baseball. Most people, especially in the South, don't know enough about professional baseball to call you "Skipper." And they feel uncomfortable calling you by your name if they don't know you. So, when they called me Coach I was irritated but I understood their frame of reference and reacted as if they had said Skipper.

In college, the head coach does a lot of teaching, but I would do very little, if any, teaching. My job would be to organize and orchestrate the activities of the team. I suddenly realized that I had no experience doing these things. I knew what I wanted the team to look like and I had some definite thoughts about plays and strategies, but I had no idea how to bring these things about.

The one thing I did know is that I would need a good bench coach and I asked if Bill Virdon was available, knowing him to be a close friend of Tal's. Everyone thought Bill was a good choice and he took the job, which made me feel a whole lot better. Bill had won more games than any Astros manager and he had been named Manager of the Year a couple of times. His presence gave me instant credibility. He was tough-minded, didn't put up with a lot of bullshit, and he knew how to run the game. I filled out my staff with former Astros: Vern Ruhle (pitching coach), Alan Ashby (bullpen coach), and Jose Cruz (first base coach). Gerry knew Mike Cubbage and Tom McCraw from his days with the Mets. We interviewed them and hired them as third base coach and hitting instructor, respectively.

With that assemblage of coaches, I started jotting down thoughts of spring training as I remembered it as a player. It had been eighteen years since I was on the field. As an announcer, I never came out early to watch the workouts. I talked with Bill and Cubby on the phone and learned that the routine was about the same as far as the workouts. But a lot of other things would be different. I had just entered another world.

Copyright © 2003 by Larry Dieker

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

Other Popular Editions of the Same Title

Search results for This Ain't Brain Surgery: How to Win the Pennant...

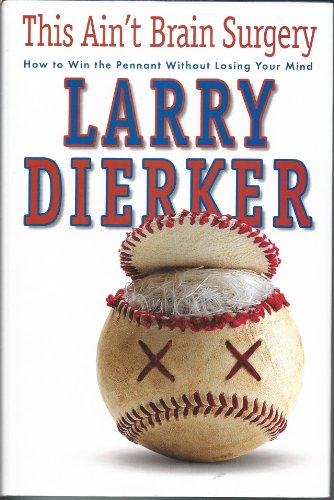

This Ain't Brain Surgery: How to Win the Pennant Without Losing Your Mind

Seller: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00079302066

This Ain't Brain Surgery: How to Win the Pennant Without Losing Your Mind

Seller: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00078460758

This Ain't Brain Surgery: How to Win the Pennant Without Losing Your Mind

Seller: BooksRun, Philadelphia, PA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. First ed. It's a preowned item in good condition and includes all the pages. It may have some general signs of wear and tear, such as markings, highlighting, slight damage to the cover, minimal wear to the binding, etc., but they will not affect the overall reading experience. Seller Inventory # 074320400X-11-1

This Ain't Brain Surgery: How to Win the Pennant Without Losing Your Mind

Seller: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Very Good condition. Very Good dust jacket. A copy that may have a few cosmetic defects. May also contain light spine creasing or a few markings such as an owner's name, short gifter's inscription or light stamp. Seller Inventory # L09F-08253

This Ain't Brain Surgery: How to Win the Pennant Without Losing Your Mind

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. Missing dust jacket; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G074320400XI4N01

This Ain't Brain Surgery: How to Win the Pennant Without Losing Your Mind

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. Missing dust jacket; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G074320400XI4N01

This Ain't Brain Surgery: How to Win the Pennant Without Losing Your Mind

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less. Seller Inventory # G074320400XI4N00

This Ain't Brain Surgery : How to Win the Pennant Without Losing Your Mind

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. First Edition. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 46672923-6

This Ain't Brain Surgery : How to Win the Pennant Without Losing Your Mind

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. First Edition. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Seller Inventory # 53248655-6

This Aint Brain Surgery: How to Win the Pennant Without Losing Y

Seller: Hawking Books, Edgewood, TX, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Very Good Condition. Five star seller - Buy with confidence! Seller Inventory # X074320400XX2