Items related to Last Dance in Havana

Synopsis

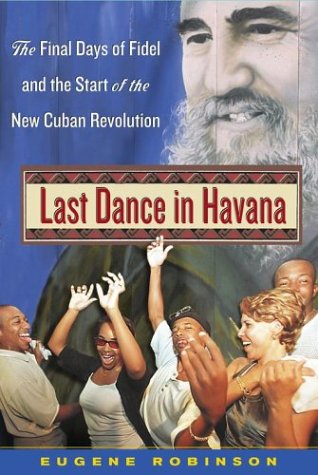

An examination of Cuban culture beneath the regime of Fidel Castro describes how regional music has thrived and become a source of potential economic gain in spite of oppression, sharing the lives of some of Cuba's musical artists as they reflect the region's politics, economy, and future. 30,000 first printing.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Chapter 1. "These People Dance"

Like most nights in Havana, this one started late. First came a long cab ride across the city, not in one of those huge, chrome-dipped Chryslers from before the Triumph of the Revolution, but in a tiny red Kia that was still under warranty. The backseat was somebody's idea of a joke. I had to sit up front, beside the driver, and even then my knees dented the dashboard and my head brushed the roof. Every pothole was pain.

It was hot -- it's always hot in Cuba in the spring -- but there was a godsend breeze that cut the humidity, or at least moved it around, drawing a lacy scrim of cirrus over the moon and stars. We sped past gloomy courtyard tenements, glimpsed through narrow doorways that were like the mouths of caves; past the faded high-rise that had been the brand-new Havana Hilton before Fidel Castro rode into town and christened it the Habana Libre, the "Free Havana"; past midcentury cabarets and cinemas with neon signs in jewellike colors, script written in rubies and emeralds. We skirted the Colón cemetery, Havana's walled necropolis, with its rococo crypts and tombs where the Triumph of the Revolution had never been announced and the rich were eternally rich. We crossed the little Almendares River, high above its narrow gorge, and careened into the genteel, shabby sprawl of a desirable neighborhood called Buenavista, whose state of decline said a lot about the nature of desire in contemporary Cuba. It was a fast trip down empty boulevards -- few Cubans have the government's permission to own cars, much less the money to buy them, and gasoline is too expensive to burn on short trips around town. Even at night people wait for the bus, and when the bus doesn't come they try to thumb rides, and when all else fails they give up and walk, half-seen figures making their way along sidewalks and medians. The night is dark in Havana, much darker than first-world night. Streetlights are anemic and few, homes sparingly lit and often shuttered. Nobody seems to sleep so there are always focal points that blaze with light and motion, but to move from one to another is to speed through a ghostly void, an emptiness peopled by shadows.

"We're going to the Tropical," the driver said as we crossed the bridge.

"Correct."

"Not the Tropicana."

"Correct."

"The Tropi-cal, right?"

"That's right."

He looked to be in his fifties, white enough to be called blanco, gray-haired, trim, no-nonsense in the way he worked. Up north in la Yuma, as Cubans call the United States -- the reference is from 3:10 to Yuma, a 1957 Glenn Ford Western, and no one in Cuba can explain why -- he might have been a midlevel insurance executive in a suburban office park. These would be his peak earning years at Wonderful Life, the time to really sock it away for the condo in Florida he had his eye on, a lovely unit off the eighth fairway in a non-sea-view development with a Seinfeldian name like Del Boca Vista. Instead he was driving halfway across Havana in the middle of the night for six or seven bucks, with practically no hope of a return fare.

If I'd said "Tropi-cana," that would have been a different story. The Tropicana was one of the most famous nightclubs in the world, the crystal Xanadu where perfect cinnamon showgirls paraded down the aisles wearing chandeliers on their heads and very little anywhere else, where Meyer Lansky and Santo Trafficante and other mobsters of renown had once commandeered the very best tables, and where tour buses now nightly deposited loads of earnest Canadians and randy Italians prepared to pay the seventy-dollar cover charge and sip mojito after overpriced mojito without complaint. There were always foreigners with pockets full of dollars coming and going from the Tropicana. My driver wouldn't have had to hang around long to find some work. But I was going to the Tropical, which was mostly patronized by Cubans -- black Cubans, at that -- and Cubans weren't supposed to take cabs like this one, which were reserved for tourists. Turi-taxis, they called them. He'd end up going all the way back downtown empty.

The driver didn't complain, though, because in turn-of-the-century Cuba his was a success story. He probably lived in a nice house, supported his wife's parents, and had enough left over to keep a mistress or two. To an average José, a run-of-the-mill patriotic worker trying to support his family on a state salary in pesos, the six or seven dollars I'd pay for this ride was half a month's pay. Even after settling up with the cab company for use of the car and the gas he burned, he could still claim membership in the elite class of this classless society: the dollar class.

We pulled into a smallish parking lot where a few dozen Cubans were lined up at a ticket booth. Behind the booth was a high wall, and there was just enough light to see that it was painted a violent pink.

"The Tropical," the driver said.

The cover was ten dollars. I bought my ticket, gave it to the man at the gate, and was swept with the crowd down a walkway, emerging into the concrete splendor of what might just be the best dance hall in the world.

"Hall" isn't quite right because the Tropical is open-air, fully exposed to the heavens. To my left was an array of tables, and behind the tables a long bar. Ahead there was a railing -- I had entered on the upper level, I now realized, and was on a balcony -- and a set of stairs on the right that led down. That was where the crowd went, so I followed. At the bottom it was clear just how vast the place was, maybe a third the size of a football field. On the left and right were rows of tables, and at the far end a big stage, trimmed in pink, bearing the legend Salón Rosado Beny Moré -- the Beny Moré Pink Room. In the middle of the space was the biggest dance floor I had ever seen.

The Tropical had been the place black Cubans went for relaxation and release back in the day, before the Triumph of the Revolution, when the Tropicana, the Montmartre, and the Sans Souci had special sections reserved for blacks -- the stage and the kitchen. Of course, President Fulgencio Batista and a few other brown-skinned officials of the republic were most welcome, but Batista preferred to curl up in his official residence or his mansion in Florida and spend the evening counting his money. Great black musicians like Chano Pozo, Israel "Cachao" López, Celia Cruz, and even Beny Moré -- Beny Moré, the genius of rhythm, the Cuban equivalent of Charlie Parker and Frank Sinatra and Chuck Berry, and Elvis Presley too, all rolled into one -- would finish their sets at the fancy clubs and then come to the Tropical and jam until dawn. The beer was ice cold and the atmosphere as hot and funky as a Mississippi juke joint. Rare was the night back then without at least one knife fight, at least one other-woman slapdown with intent to kill, and at least a handful of patrons deposited in a corner to sleep it off. Since Castro and his moralizing rebels arrived, nights at the Tropical offered less drama. But there was still something raffish and wonderful about the place, still an electric charge of possibility in the air.

The tables were almost all full, and this was a different crowd than at the other music halls around Havana, where sometimes there were more tourists than locals. The Tropical crowd was mostly black and practically all Cuban. Recorded music was playing over the sound system, recent hits by the great Cuban salsa bands. I sipped beer and watched the two couples at the table across the dance floor from me. One of the men, overweight and dressed in a light-green polo shirt and faded jeans, was already quite drunk and kept getting up to dance alone in a wobbly, meandering little three-step. He kept perfect time, but always a consistent fraction of a second behind the beat. Every once in a while he would lean so far off the vertical that I was sure he would fall, but he always caught himself, barely, as if his internal gyroscope had just enough spin left to snap him upright one last time. At that point his wife would roll her eyes, get up, dance with him for a moment, and then lead him back to the table, where he would pour another drink from a fast-dwindling bottle of three-year-old Havana Club rum.

The music stopped, the lights went down, and an announcer with the deep voice, toothy smile, and perfect hair of a game-show host came out to launch the preliminaries.

First, believe it or not, was a fashion show. After forty years of socialism, economic embargo, and principled rejection of bourgeois comforts, nobody should go to Cuba for the fashion. The clothes on display at the Tropical looked unexceptional and the fabrics were cheap, clinging where they should have draped and draping where they should have clung. Women in the audience paid rapt attention, though, and clapped warmly at the end, proving that all fashion is local.

Next came a comic who spoke so fast and used so much slang that I missed every single one of his punch lines. I did make out that part of his act was a long nostalgic bit about the old days, when Cuba was a mighty weapon in the Cold War and Havana was full of clumsy hayseed Russian sailors. The crowd found this material hilarious, proving that all humor is local too.

Finally the announcer came back to bring on the headline act: Bamboleo, one of the hottest salsa orquestas in Havana. The lights dimmed. The musicians came out, a dozen shadow-men taking their stations, quietly preparing for battle. There was a pause, and then a male voice said, "Un', dos, un', dos, tres..."

Kaboom.

The horns played a fanfare, the bass answered with a bluesy lick, the four percussionists set up a mighty clatter. Four singers bounded onstage, two men and two women. For a moment I don't think I was able to breathe.

The two female singers were the focus of the show and the cause of my asphyxia. Both were lithe and brown skinned, both were surpassingly beautiful, and both had their hair cut very short, mannishly short, which is a rare look in Cuba. They weren't quite a matched set -- one, whom I later learned was named Vannia, was tall and leggy; the other, Yordamis, was petite and pixieish. Vannia had taken the further step of straightening her hair and dyeing it a rich and shocking blond, while Yordamis kept hers in a short dark afro, but they wore identical slinky silver gowns that sparkled in the stage lights, and they moved in perfect tandem. They seemed unreal, idealized, as if they were avatars or sirens instead of real women. They were transfixing.

I looked around and realized that the Tropical, in that instant, had exploded in sound and movement. The band was playing with power, filling the open sky with music so loud it made ripples in a glass of beer at twenty-five paces. The crowd screamed as if for life itself. Scores of young people had rushed the stage and were already standing four deep, moving to the music, singing along with the tune. And the endless dance floor had magically filled, giving itself over to some powerful enchantment.

Enchantment, witchcraft, magic, Santería -- these were the only possible explanations for what I was witnessing. Across the extent of this huge space, filling it to capacity and beyond, couples were dancing. But "dancing" does not begin to tell what they were doing. They were whipping, they were twirling. They were circling, diving beneath locked arms, embracing. They were bumping, grinding, releasing, spinning, caressing, all but making love. They were doing all these things in a dense crowd, somehow coordinating their moves so that whenever a man swung his partner toward a given point on the floor, the man or woman in the neighboring couple who was occupying that space somehow moved out of the way just in time, gracefully shifting into another space that a millisecond earlier had likewise been magically vacated. At first it looked to me as if some higher intelligence were guiding the movements of each of these hundreds of people. But then, as I continued to watch, a new metaphor took over: This was an exercise in massively parallel computation, many minds each solving its own bit of an otherwise unsolvable problem. No one genius could have attended to so many vital details so perfectly. This group movement was decentralized but coordinated, almost like flocking or schooling but not at all instinctive, not in the least unconscious. It was brilliantly human and clever and aware, both spontaneous and purposeful, and it was one of the most stirring and beautiful sights I have ever seen.

Individual couples were no less amazing. All good dance partners look as if they're reading each other's minds, but this was speed reading. These people were channeling Evelyn Wood. A man would spin his partner, and while she was spinning he would circle to the left or the right, and when she came out of the spin she'd know just where he was, know that he had gone left and not right, or right and not left. And then without pause he'd spin her the other way, only this time he wouldn't move at all, but she'd anticipate that too and know where to find him. Then they'd cross hands and start circling each other, at the same time rotating so that sometimes they faced the same direction and other times in opposite directions, passing their locked arms above their heads and across their shoulders and behind their backs, managing to go around and around, back and forth, always to the beat, without ever breaking their gentle grasp. They'd separate, riff for a while, then rejoin. They'd hear a particular rhythm from one of the drummers and it would suggest an appropriate dance step, and they'd ease into it simultaneously, seamlessly, before flowing on to the next. This was not just about moving to the beat, or even about looking graceful in motion. Event followed event followed event in this dancing. Each couple was writing its own private narrative, a tropical saga told in a language that an outsider like me could appreciate, even begin to understand, but never really learn to speak.

They say that great salsa dancers are made, not born. Feeling the rhythm is hardly even a beginning; there is an enormous amount of technique to learn, a huge vocabulary of moves and a complicated syntax for stringing them together. Application counts more than talent. But as with gymnastics or tennis, you have to start young. It was obvious that anyone who hadn't learned this language from birth could drag his bones across dance floors night after night until the end of time and never learn to do it like the crowd at the Tropical.

Bamboleo would have blown the roof off the joint, if it had had one. The band was tight and disciplined, instantly responsive to nods and gestures from the keyboard player, a stocky chestnut-skinned man wearing red pants, a red vest over a white T-shirt, and a bright red do-rag on his head. These clearly were fabulous musicians, with the kind of technique that comes from years of scales and finger exercises. But this show was as much about dance as music. Vannia and Yordamis had a signature move, a kind of exaggerated, undulating, dirty-dancing grind that made men desire, women aspire, and chiropractors see dollar signs. Most of the youngsters in the crowd could do it too, and there were moments that night when the Tropical was like a waving field of sea grass, washed by a powerful current that pulsed to a three-two Latin beat.

The energy level actually rose as the morning rolled on. When Vannia sang the opening bars of Bamboleo's biggest hit, a hit-the-road-Jack revenge anthem called "Ya No Hace Falta" ("No Longer Needed"), the kids up near the stage, hundreds of them by now, cro...

From The Washington Post

"Another Cuba book?" my wife asks with a laugh whenever a slightly bulky tan mailer arrives for me. The flow of books about the Caribbean's largest island has accelerated in recent years to the point where CAUTION: FREQUENT FLOODING signs should be posted. The books have a sameness to them, though, whether they're concerned with public policy or private lives. But Eugene Robinson's Last Dance in Havana has the rare distinction of showing the influence of the public on the private, and it's a most satisfying look at Cuba today.

For more than 10 years now, the Havana street has led the Cuban government. Whenever a phenomenon was successful with ordinary Cubans, the state took it over. Private restaurants in people's homes were neither legal nor illegal in the early 1990s. When that entrepreneurial activity became popular with foreigners, the government started regulating it. Likewise, lodging international visitors was not forbidden, and became widespread -- and the state moved in to control that enterprise as well. The street always offered a far better pesos-for-dollars exchange rate than the state, until one day government kiosks popped up all over town with the street rate, effectively usurping the freelance trade. And, as Last Dance in Havana shows, when hip-hop culture became too popular to ignore, when the scene was too big to overlook, when rappers were routinely getting overseas interest, the government moved in front of the phenomenon and legitimized it as "an authentic expression of Cuban culture."

The street, the people, the lumpen -- in short, friends and neighbors -- are the stars of Last Dance in Havana. Robinson, a former overseas correspondent and foreign editor for The Washington Post who now heads its Style section, has performed an adroit task, mixing with Cubans in dank night clubs, crowded homes and poorly equipped concert halls to give us a credible and at times hopeful look at the daily struggle on this "gorgeous wasteland of excellence and decay." His book is well-reasoned and lively, informative and animated. And he uses dance and music to tell the larger picture of Fidel Castro, his government and its dominance.

Castro, who turns 78 next month, is portrayed as "impresario" of the "Cuban carnival . . . barker, ringmaster, daredevil, lion tamer, roustabout, tightrope walker, but never clown. He . . . wore the island of Cuba like a mood ring." When Soviet largesse disappeared, he "had to shift, give way, step left and then right and then left again -- he had to dance like a youngster again, and by now he must know that he can never rest. He will dance until he dies."

Robinson makes a good case for his claim that to grasp where the country stands you must appreciate its perpetual undercurrents: music and dance. "Those who make the music," he asserts, "are the real journalists, analysts, social commentators." As for dance, "Cubans move through their complicated lives the way they move on the dance floor; dashing and darting and spinning on a dime, seducing joy and fulfillment and next week's supply of food out of a broken system. Then at night they take to the real dance floors and invent new steps." The author characterizes one couple's moves as "classical ballet on amphetamines."

Last Dance follows individual musicians and politicos -- yes, Cuba has the latter, and sometimes they're the same as the former -- as they struggle to gain acceptance, prominence and their daily bread. Robinson uncovers the music scene that "coexisted with the official, sanctioned world of Fidel's revolution but had its own mores and hierarchies, even its own economy." He follows the enormously popular group Bamboleo as they change personnel and musical style over time. He portrays the loyal band Los Van Van as a combination of the Beatles, the Rolling Stones and Bruce Springsteen. Visionary Juan de Marcos, the country's leading music producer, tells Robinson: "Cuban music is Afro-Cuban music. There are no whites in Cuba. There are people who think they are white, but they are all African."

Finally there is hip-hop which, with government support, is the focus of international festivals, neighborhood gatherings and widespread propaganda. "You had to listen to what kids were playing on their boom boxes," Robinson explains, "you had to notice how, when you got away from the tourist zones, the soundtrack switched from Buena Vista nostalgia to hard-edged rap." The hip-hop generation "knew all about the promises the Cuban revolution had broken and very little about the promises it had kept." Rap touched on subjects such as rough police treatment and the daily struggle, but never questioned the premises of the revolution itself.

Into this milieu strolled Clan 537, raperos whose song "¿Quién Tiró la Tiza?" ("Who Threw the Chalk?") touched that raw nerve by focusing not just on race but class and inequality. The song, as Robinson describes its trajectory, leapt out of hip-hop culture into mainstream Havana by word of mouth and worn-out cassettes; eventually, by popular demand, hip-hop clubs and radio stations put it in heavy rotation. To counteract this lively song mocking the very foundations of the regime, the government put out its own answer song, so poorly conceived and performed that it got laughed out of existence. As for Clan 537's hit, suddenly it was no longer played by deejays in the clubs or on the air. "Every loudspeaker controlled by the state stopped playing it." The song, a bureaucrat in the music industry told a friend of the author's with a straight face, "has been suspended." That's when the government withdrew much of its support from the hip-hop world. Hip-hop's expression of Cuban culture had become a bit too authentic.

The book is not without its faults. The breezy, informative and friendly writing occasionally suffers from unnecessarily repeated introductions of people, ideas and places, a surfeit of metaphors -- and could we do with fewer cabbies quoted? Sometimes a good editor needs a good editor. In all, though, Last Dance in Havana gives as reliable a sense as you are likely to find of what it's like to live in Cuba's capital right now, who your neighbors are and the soundtrack that accompanies you throughout the day and night.

For a thorough schooling in what preceded today's music scene, you could do no better than to read Ned Sublette's Cuba and Its Music, a well-written and brilliantly researched book that explains how music on the island has been influenced through the centuries by immigration, warfare, slavery, tourism, poetry, sugar cane, miscegenation and spirituality. Its detailed, first-rate scholarship makes Cuba and Its Music valuable and worthy, yet it will appeal to anyone with a jones for Cuba and its culture. It starts long before Columbus with the development of Cuba's parents, Spain and Africa, and ends in the early 1950s. (A second volume is said to be in the works.)

"The masked ball was the perfect metaphor for the time," Sublette writes of the mid-19th century, when slavery prospered under Spanish rule, "gaiety masking the great tension in the air." It is this sort of observation that Sublette, a musician, producer, co-founder of a small record label and for many years a producer of the program "Afropop Worldwide" on public radio, makes so well. He tells us that many Cuban musicians abandoned the country between 1930 and 1936 during some exceptionally autocratic, unstable and violent years, yet in 1937 "an explosion of pent-up creativity appeared on every musical front." Sublette leaves nothing out, even making the outlandishly logical suggestion that Elvis Presley's early music and movies were derivative of Cuban culture. There have been few, if any, social and political developments in Cuba, he implies, that have not been inextricably related to music and its diffusion. The musicians who created the extraordinary sounds emanating from the island during the last five centuries are the true heroes of Cuba and Its Music. It ranks with works on the same theme by Alejo Carpentier and Helio Orovio.

Copyright 2004, The Washington Post Co. All Rights Reserved.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherFree Press

- Publication date2004

- ISBN 10 0743246225

- ISBN 13 9780743246224

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages288

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 3.50

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Last Dance in Havana

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00066227652

Quantity: 1 available

Last Dance in Havana

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00065904204

Quantity: 1 available

Last Dance in Havana

Seller: More Than Words, Waltham, MA, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. . . All orders guaranteed and ship within 24 hours. Before placing your order for please contact us for confirmation on the book's binding. Check out our other listings to add to your order for discounted shipping. Seller Inventory # BOS-I-09b-01451

Quantity: 1 available

Last Dance in Havana

Seller: BookHolders, Towson, MD, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. [ No Hassle 30 Day Returns ][ Ships Daily ] [ Underlining/Highlighting: NONE ] [ Writing: NONE ] [ Edition: first ] Publisher: Free Press Pub Date: 7/6/2004 Binding: Hardcover Pages: 288 first edition. Seller Inventory # 6031590

Quantity: 1 available

Last Dance in Havana

Seller: Irish Booksellers, Portland, ME, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. SHIPS FROM USA. Used books have different signs of use and do not include supplemental materials such as CDs, Dvds, Access Codes, charts or any other extra material. All used books might have various degrees of writing, highliting and wear and tear and possibly be an ex-library with the usual stickers and stamps. Dust Jackets are not guaranteed and when still present, they will have various degrees of tear and damage. All images are Stock Photos, not of the actual item. book. Seller Inventory # 19-0743246225-G

Quantity: 1 available

Last Dance in Havana

Seller: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Good condition. Very Good dust jacket. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Bundled media such as CDs, DVDs, floppy disks or access codes may not be included. Seller Inventory # L18J-01506

Quantity: 1 available

Last Dance in Havana

Seller: The Maryland Book Bank, Baltimore, MD, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Used - Very Good. Seller Inventory # 15-B-1-0051

Quantity: 1 available

Last Dance in Havana: The Final Days of Fidel and the Start of the New Cuban Revolution

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.45. Seller Inventory # G0743246225I4N00

Quantity: 1 available

Last Dance in Havana: The Final Days of Fidel and the Start of the New Cuban Revolution

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.45. Seller Inventory # G0743246225I3N10

Quantity: 1 available

Last Dance in Havana : The Final Days of Fidel and the Start of the New Cuban Revolution

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 39518003-75

Quantity: 2 available