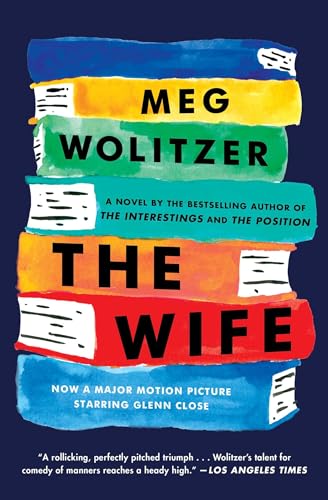

Items related to The Wife: A Novel

Synopsis

Now a major motion picture starring Glenn Close in her Golden Globe–winning role!

One of bestselling author Meg Wolitzer’s most beloved books—an “acerbically funny” (Entertainment Weekly) and “intelligent...portrait of deception” (The New York Times).

The Wife is the story of the long and stormy marriage between a world-famous novelist, Joe Castleman, and his wife Joan, and the secret they’ve kept for decades. The novel opens just as Joe is about to receive a prestigious international award, The Helsinki Prize, to honor his career as one of America’s preeminent novelists. Joan, who has spent forty years subjugating her own literary talents to fan the flames of his career, finally decides to stop.

Important and ambitious, The Wife is a sharp-eyed and compulsively readable story about a woman forced to confront the sacrifices she’s made in order to achieve the life she thought she wanted. “A rollicking, perfectly pitched triumph...Wolitzer’s talent for comedy of manners reaches a heady high” (Los Angeles Times), in this wise and candid look at the choices all men and women make—in marriage, work, and life.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Meg Wolitzer’s novels include The Female Persuasion; Sleepwalking; This Is Your Life; Surrender, Dorothy; and The Position. She lives in New York City.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Chapter One

The moment I decided to leave him, the moment I thought, enough, we were thirty-five thousand feet above the ocean, hurtling forward but giving the illusion of stillness and tranquility. Just like our marriage, I could have said, but why ruin everything right now? Here we were in first-class splendor, tentatively separated from anxiety; there was no turbulence and the sky was bright, and somewhere among us, possibly, sat an air marshal in dull traveler's disguise, perhaps picking at a little dish of oily nuts or captivated by the zombie prose of the in-flight magazine. Drinks had already been served before takeoff, and we were both frankly bombed, our mouths half open, our heads tipped back. Women in uniform carried baskets up and down the aisles like a sexualized fleet of Red Riding Hoods.

"Will you have some cookies, Mr. Castleman?" a brunette asked him, leaning over with a pair of tongs, and as her breasts slid forward and then withdrew, I could see the ancient mechanism of arousal start to whir like a knife sharpener inside him, a sight I've witnessed thousands of times over all these decades. "Mrs. Castleman?" the woman asked me then, in afterthought, but I declined. I didn't want her cookies, or anything else.

We were on our way to the end of the marriage, heading toward the moment when I would finally get to yank the two-pronged plug from its holes, to turn away from the husband I'd lived with year after year. We were on our way to Helsinki, Finland, a place no one ever thinks about unless they're listening to Sibelius, or lying on the hot, wet slats of a sauna, or eating a bowl of reindeer. Cookies had been distributed, drinks decanted, and all around me, video screens had been arched and tilted. No one on this plane was fixated on death right now, the way we'd all been earlier, when, wrapped in the trauma of the roar and the fuel-stink and the distant, braying chorus of Furies trapped inside the engines, an entire planeload of minds -- Economy, Business Class, and The Chosen Few -- came together as one and urged this plane into the air like an audience willing a psychic's spoon to bend.

Of course, that spoon bent every single time, its tip drooping down like some top-heavy tulip. And though airplanes didn't lift every single time, tonight this one did. Mothers handed out activity books and little plastic bags of Cheerios with dusty sediment at the bottom; businessmen opened laptops and waited for the stuttering screens to settle. If he was on board, the phantom air marshal ate and stretched and adjusted his gun beneath a staticky little square of Dynel blanket, and our plane rose in the sky until it hung suspended at the desired altitude, and finally I decided for certain that I would leave my husband. Definitely. For sure. One hundred percent. Our three children were gone, gone, gone, and there would be no changing my mind, no chickening out.

He looked over at me suddenly, watched my face, and said, "What's the matter? You look a little...something."

"No. It's nothing," I told him. "Nothing worth talking about now, anyway," and he accepted this as a good-enough answer, returning to his plate of Tollhouse cookies, a small belch puffing his cheeks out froglike, briefly. It was difficult to disturb this man; he had everything he could possibly ever need.

He was Joseph Castleman, one of those men who own the world. You know the type I mean: those advertisements for themselves, those sleepwalking giants, roaming the earth and knocking over other men, women, furniture, villages. Why should they care? They own everything, the seas and mountains, the quivering volcanoes, the dainty, ruffling rivers. There are many varieties of this kind of man: Joe was the writer version, a short, wound-up, slack-bellied novelist who almost never slept, who loved to consume runny cheeses and whiskey and wine, all of which he used as a vessel to carry the pills that kept his blood lipids from congealing like yesterday's pan drippings, who was as entertaining as anyone I have ever known, who had no idea of how to take care of himself or anyone else, and who derived much of his style from The Dylan Thomas Handbook of Personal Hygiene and Etiquette.

There he sat beside me on Finnair flight 702, and whenever the brunette brought him something, he took it from her, every single cookie and smokehouse-treated nut and pair of spongy, throwaway slippers and steaming washcloth rolled Torah-tight. If that luscious cookie-woman had stripped to her waist and offered him one of her breasts, mashing the nipple into his mouth with the assured authority of a La Leche commandant, he would have taken it, no questions asked.

As a rule, the men who own the world are hyperactively sexual, though not necessarily with their wives. Back in the 1960s, Joe and I leaped into beds all the time, occasionally even during a lull at cocktail parties, barricading someone's bedroom door and then climbing a mountain of coats. People would come banging, wanting their coats back, and we'd laugh and shush each other and try to zip up and tuck in before letting them enter.

We hadn't had that in a long time, though if you'd seen us here on this airplane heading for Finland, you'd have assumed we were content, that we still touched each other's sluggish body parts at night.

"Listen, you want an extra pillow?" he asked me.

"No, I hate those doll pillows," I said. "Oh, and don't forget to stretch your legs like Dr. Krentz said."

You'd look at us -- Joan and Joe Castleman of Weathermill, New York, and, currently, seats 3A and 3B -- and you'd know exactly why we were traveling to Finland. You might even envy us -- him for all the power vacuum-packed within his bulky, shopworn body, and me for my twenty-four-hour access to it, as though a famous and brilliant writer-husband is a convenience store for his wife, a place she can dip into anytime for a Big Gulp of astonishing intellect and wit and excitement.

People usually thought we were a "good" couple, and I suppose that once, a long, long time ago, back when the cave paintings were first sketched on the rough walls at Lascaux, back when the earth was uncharted and everything seemed hopeful, this was true. But soon enough we moved from the glory and self-love of any young couple to the green-algae swamp of what is delicately known as "later life." Though I'm now sixty-four years old and mostly as invisible to men as a swirl of dust motes, I used to be a slender, big-titted blond girl with a certain shyness that drew Joe toward me like a hypnotized chicken.

I don't flatter myself; Joe was always drawn to women, all kinds of them, right from the moment he entered the world in 1930, via the wind tunnel of his mother's birth canal. Lorna Castleman, the mother-in-law I never met, was overweight, sentimentally poetic and possessive, loving her son with a lover's exclusivity. (Some of the men who own the world, on the other hand, were ignored throughout their childhoods -- left sandwichless at lunchtime in bleak school yards.)

Lorna not only loved him, but so did her two sisters who shared their Brooklyn apartment, along with Joe's grandmother Mims, a woman built like a footstool, whose claim to fame was that she made "a mean brisket." His father, Martin, a perpetually sighing and ineffectual man, died of a heart attack at his shoe store when Joe was seven, leaving him a captive of this peculiar womanly civilization.

It was typical, the way they told him his father was dead. Joe had just come home from school and, finding the apartment unlocked, he let himself in. No one else was home, which was unusual for a household that always seemed to contain some woman or other, hunched and busy as a wood sprite. Joe sat down at the kitchen table and ate his afternoon snack of yellow sponge cake in the moony, stupefied way that children have, a constellation of crumbs on the lips and chin.

Soon the door to the apartment swung open again and the women piled in. Joe heard crying, the emphatic blowing of noses, and then they appeared in the kitchen, crowding around the table. Their faces were inflamed, their eyes bloodshot, their carefully constructed hairdos destroyed. Something big had happened, he knew, and a sense of drama rolled inside him, almost pleasurably at first, though that would immediately change.

Lorna Castleman knelt down beside her son's chair, as though about to propose. "Oh, my brave little fella," she said in a hoarse whisper, tapping her finger adhesively against his lips to remove crumbs, "it's just us now."

And it was just them, the women and the boy. He was completely on his own in this female world. Aunt Lois was a hypochondriac who spent her days in the company of a home medical encyclopedia, poring over the sensual names of diseases. Aunt Viv was perpetually man-obsessed and suggestive, forever turning around to display a white length of back revealed in an unclenched zipper's jaw. Tiny, ancient Grandmother Mims was in the middle of it all, commandeering the kitchen, triumphantly yanking a meat thermometer from a roast as though it were Excalibur.

Joe was left to wander the apartment like a survivor of a wreck he couldn't even remember, searching for other forgetful survivors. But there were none; he was it, the beloved boy who would eventually grow up and become one of those traitors, those cologne-doused rats. Lorna had been betrayed by her husband's early death, which had arrived with no preamble or warning. Aunt Lois had been betrayed by her own absence of sensation, by the fact that she'd never felt a thing for any man except, from afar, Clark Gable, with his broad shoulders and easy-grip-during-sex jug ears. Aunt Viv had been betrayed by legions of men -- sleepy, sexy, toying men who telephoned the house at all hours, or wrote her letters from overseas, where they were stationed.

The women who surrounded Joe were furious at men, they insisted, yet they also insisted that he was exempt from their fury. Him they loved. He was hardly a man yet, this small, bright boy with the genitals like marzipan fruit and the dark, girlish curls and the precocious reading skills and, since his father died, the sudden inability to sleep at night. He'd roll around in bed for a while trying to think soothing thoughts about baseball or the bright, welcoming pages of comic books, but always he ended up picturing his father, Martin, standing on a puff of cloud in heaven and sadly holding out a pair of saddle shoes still nestled in their box.

Finally, around midnight, Joe would give in to his insomnia, getting up and going into the dark living room, playing a game of jacks alone in the middle of the rag rug. During the day he sat on that same rug at the women's feet while they kicked off their pumps. As he listened to their unhappy, overlapping sagas, he knew that in some unstated way he ruled the roost and always would.

When Joe was finally sprung from the household, he found himself both enormously relieved and fully educated. He knew some things about women now: their sighs, their undergarments, their monthly miseries, their quest for chocolate, their cutting remarks, their spiny pink curlers, the time line of their bodies, which he'd viewed in unsparing detail. This was what would be in store for him if he fell for a woman one day. He'd be forced to watch her shift and change and collapse over time; he'd be helpless to stop it from happening. Sure, she might be desirable now, but one day she would be nothing but a giver of brisket. So he chose to forget what he knew, to pretend that the knowledge had never penetrated his small, perfect head, and he left this all-female revue and stepped onto the creaking train that sweeps people from their lesser boroughs into the thrilling chaos of the only borough that really counts: Staten Island.

Just a joke.

Manhattan, 1948. Joe rises from the fumes of the subway and enters the gates of Columbia University, meeting up with other brainy, soulful boys. Declaring himself an English major, he joins the staff of the undergraduate literary magazine and immediately publishes a story about an old woman who thinks back on her life in a Russian village (wormy potatoes, frozen toes, etc., etc.). The story is laughable and poorly written, as his critics will later point out while pawing through crates of his juvenilia. However, a few of them will insist that the exuberance of Joe Castleman's fiction is already in place. He trembles with excitement, loving his new life, enjoying the feverish pleasure of going with college friends to Ling Palace in Chinatown and ingesting his first prawns in black-bean sauce -- his first prawns of any kind, in fact, for nothing that calls a shell its home has ever entered Joe Castleman's lips.

Those lips also receive the lips and tongue of his first female, and in short order his virginity is removed with the crack precision of a dental extraction. The remover is a needy but energetic girl named Bonnie Lamp who attends Barnard College, where, according to Joe and his friends, she has been given a merit scholarship in nymphomania. Joe is captivated by doe-eyed Bonnie Lamp, as well as by the amazing act of sexual intercourse. And, by association, he's captivated by himself. After all, why shouldn't he be? Everyone else is.

When he makes love to Bonnie, entering and slowly exiting, he's impressed by the way their interlocking parts emit little, rhythmic clicks, like a distant secretary's heels walking across linoleum. He's also fascinated by the other sounds Bonnie Lamp makes independently. In her sleep she seems to mew like a kitten, and he watches her with a strange mixture of tenderness and condescension, imagining that she's dreaming about a ball of yarn, a plate of milk.

A ball of yarn, a plate of milk, and thou, he thinks, in love with words, with women. Their pliant bodies fascinate him -- all those swells and flourishes. His own body fascinates him equally, and when his roommate is elsewhere, Joe takes the mirror down from its nail on the wall and gets a long look at himself: his chest with its careless littering of dark hair, his torso, his surprisingly large penis for such a short and wiry person.

He imagines his own circumcision, so many years earlier, sees himself struggle in a strange bearded man's arms, accepting a thick pinkie finger dipped in kosher wine, then sucking wildly on that pinkie, mining it for nonexistent fluid, and instead finding only a whorled surface with no hidden pinhole source of milk. But in this image the painting of sweet wine down his gullet dazes him, makes a hash of all the proud faces around him. His eight-day-old eyes close, then open, then close again, and eighteen years later he awakens, a grown man.

Time passes for Joe Castleman, and he stays on at Columbia for graduate school, and during this period there's a shift in the environment. It's not just the change of seasons, or the continual bloom of new buildings with their crosshatches of scaffolding. Nor is it simply the small socialist gatherings Joe attends, though he hates to be a joiner, can't stand to be part of a group, even for a cause he believes in like this one, sitting earnest and cross-legged on someone's mildewed carpet and just listening, just taking information in, not offering anything of his own. And it's not only the increasing drumbeat of early 1950s bohemia, which leads Joe into a few narrow, underlit bongo clubs, where he develops an instant and lifelong taste for smoking grass. It's more that the world is truly opening up to him, oysterlike, and he walks inside it, tentatively touching the smooth ridge...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherScribner

- Publication date2004

- ISBN 10 0743456661

- ISBN 13 9780743456661

- BindingPaperback

- LanguageEnglish

- Number of pages219

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Wife A Novel

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Acceptable. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00060989327

Quantity: 5 available

The Wife: A Novel

Seller: Orion Tech, Kingwood, TX, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Good. Seller Inventory # 0743456661-3-22721650

Quantity: 2 available

The Wife: A Novel

Seller: Orion Tech, Kingwood, TX, U.S.A.

paperback. Condition: Fair. Seller Inventory # 0743456661-4-29326747

Quantity: 2 available

The Wife: A Novel

Seller: Gulf Coast Books, Memphis, TN, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Fair. Seller Inventory # 0743456661-4-21320522

Quantity: 1 available

The Wife: A Novel

Seller: Your Online Bookstore, Houston, TX, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Good. Seller Inventory # 0743456661-3-20370406

Quantity: 1 available

The Wife: A Novel

Seller: Gulf Coast Books, Memphis, TN, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Good. Seller Inventory # 0743456661-3-20797752

Quantity: 4 available

The Wife: A Novel

Seller: Your Online Bookstore, Houston, TX, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Fair. Seller Inventory # 0743456661-4-20068872

Quantity: 1 available

The Wife A Novel

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00062981505

Quantity: 10 available

The Wife: A Novel

Seller: ZBK Books, Carlstadt, NJ, U.S.A.

Condition: acceptable. Used book - May contain writing, notes, highlighting, bends or folds. Text is readable, book is clean, and pages and cover mostly intact. May show normal wear and tear. Item may be missing CD. May include library marks. Fast Shipping. Seller Inventory # ZWM.8HS7

Quantity: 1 available

The Wife: A Novel

Seller: ZBK Books, Carlstadt, NJ, U.S.A.

Condition: acceptable. Used book - May contain writing, notes, highlighting, bends or folds. Text is readable, book is clean, and pages and cover mostly intact. May show normal wear and tear. Item may be missing CD. May include library marks. Fast Shipping. Seller Inventory # ZWM.1TGK

Quantity: 1 available