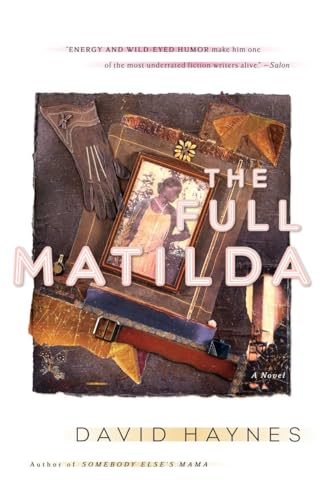

Items related to The Full Matilda: A Novel

Synopsis

Matilda Housewright hails from a long line of venerable and well-respected African American retainers—her family has been in “service” for generations, serving Washington, D.C., politicos and other upper-crust families. The daughter of the indispensable majordomo Jacob Housewright, Matilda grew up in the house of a powerful D.C. senator and learned how to be a hostess extraordinaire—and has perfected the art of service. But after her father dies and she starts a catering business with her brother, Matilda begins to question who she is and what, exactly, she’s serving. Told in the voices of the men in her life, with connecting interludes from Matilda, the reader indeed gets The Full Matilda, a glorious glimpse inside the intriguing life of a captivating woman in the midst of change as she maneuvers through a web of secrets, expectations, and worn-out social mores.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

DAVID HAYNES is an assistant professor of creative writing at the Southern Methodist University in Texas. Named one of America's best young novelists by Granta, Haynes has had his short stories recorded for National Public Radio’s Selected Shorts. He is the author of several critically acclaimed novels, including All American Dream Dolls, Live at Five, and Somebody Else’s Mama.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

The Full Matilda

We Housewrights have never been famous. We have never been the sort of people whose names you find mentioned in the society pages, nor anywhere else in the newspaper, for that matter. If you must know, my father thought it tasteless the way a certain sort of person paraded his life before the public, as if that person’s entire raison d’Ítre were to be ever part of some seamy side show, part of some ongoing masked ball. In Father’s mind, the higher the person’s station in life, the greater the shame at said person’s lack of good judgment about such matters.

It is also the case that the nature of our family business has always been about being, at the optimum, mostly invisible. If my father did his job well (and my father always did his job well), you would not notice that he had been there at all.

That being said, those who traveled certain corridors in our nation’s capital did know the Housewright name. If you travel such corridors yourself, I’m sure you already understand how these things work.

Let’s say you are a seasoned politician and you have only recently been elected as the junior senator from your state. Big things are expected of you as a member of our nation’s most prestigious legislative body, and big things are expected as well on the social horizon. Back in your home state, you have achieved for yourself and your family a certain prominence, and, of course, you are used to the finer things that life has to offer, to a gracious standard of living. It would therefore be of critical interest to you in your newest role that your affairs at every level, both in the halls of Congress as well as in your home, be arranged in a way that stand to secure you the prominent status you fully expect to be yours.

You would soon come to discover that the rules are different in the District of Columbia. This city is unlike any other you’ve known. To be specific, while Washington has always been and always will be a community in love with money, having money in this town buys you almost nothing in terms of social acceptance or prestige. The things that matter on your new turf are subtler and yet more telling than the bottom line of your portfolio. It makes a difference, for example, the address of your residence. It makes a difference how and when you entertain. One would not, for instance, even consider hosting a dinner party on those evenings when certain figures of prominence are known to be doing the same. In the same vein, you would be expected to know to whom invitations must always be extended, and which others are better excluded from your lists. When seating your guests for dinner, certain individuals are never seated next to others. This ambassador prefers a particular cigar with his brandy, while that one delights in a bowl of soft mints at his fingertips; and all of this information is critical. Unfortunately, you, being new to town, would have no way of knowing such things. It would be in your best interest, therefore, to retain the services of someone who does know, someone to run your household in a way that establishes you in Washington as a man of stature and of good character. You inquire around. And were the name Housewright not the first you heard, it would come awfully high on the list of persons who might be of assistance in these matters.

We Housewrights have a long and distinguished history in service. In his later years, Grandfather Josiah ran the estate of a wealthy industrialist up along the Hudson River, in New York. He’d begun his career with the livery of a branch of that same family here in Washington, and with his employer had occasion to return to the capital a number of times over his working life. (As you know, the sort of people who require our services tend to reside in our capital city at least once in any given generation.)

And when in Maryland, travelers, there is a plantation along the Severn River I recommend that you visit. There, near the fireplace in the central hall, you will find a daguerreotype of those who, around 1845, lived and worked in the main house. The suited gentleman behind the owner, the one with the crisp white tea towel over his arm, that would be Ezekiel, Josiah Housewright’s father.

My own father began his career working in the kitchen of the house his father ran. Jacob, Cyrus, JulieAnne, and Bess. Those were the Housewright siblings. My father’s employers insisted the children be schooled right alongside their own, that is, up until the time theirs were sent away to preparatory academies (finishing schools for the daughters). In the evenings and on weekends, my father, my uncle, and my aunts were expected to work with their parents, taking care of all that needed taking care of in households of that magnitude. Grandfather Josiah viewed this as something like an apprenticeship for his children, assuming, as one would, that his progeny would succeed him in the family profession. From what I was told, the man was something of a martinet when it came to standards and results. I can imagine him ripping the sheets from an improperly prepared bed and insisting that whichever child were responsible for the clumsy attempt return the bedding to the ironing board before trying it again on the mattress.

JulieAnne and Bess worked with their mother up on the second floor, supplementing the domestic staff. Mending, dusting, that sort of thing. I was told that my uncle Cyrus fell in love with horses and couldn’t be kept from the stables. He trained to be a groom and a driver. Father made what might seem an odd choice. He opted to work in the kitchen.

Now as you can imagine, there is nothing glamorous about kitchen work. Peeling vegetables, scrubbing burnt casseroles and roasting pans. But old Jacob was no fool. You see, at an early age, my father figured out that the best place to keep tabs on everything that went on in the household would be right there in the kitchen. The family who owned the house would drop through to visit and sample whatever delicacy the cook was preparing and to inform her as to who might be expected for supper that evening. The household staff took their meals in the kitchen, as did those who maintained the grounds. In the winter anyone who had been outside would at some point in the day steal a few moments of warmth near the stove. Almost anyone on the staff could be counted on to share the latest gossip: the fact that “Sir” had ordered that Winthrop boy not be admitted to the house again unless accompanied by that no-good father of his, and how “Herself” (the disrespectful appellation some used for the wife of the household) had pitched a royal fit over being served a tough slice of lamb.

My father would linger stealthily over his scrubbing or chopping, and he would gather all of this talk into his memory. I don’t believe he ever wrote down a word. He possessed one of those minds, one of those memories, where once he had heard a man’s name, he never forgot it, nor would he forget the man’s preferred brand of whisky or favorite dessert. And so it was that when he was ready to secure his own position, Jacob Housewright had already trained himself to be the most diligent and attentive accessory an important man could ever hope to employ.

The gentleman of the house expects a vehicle at the ready at all times, a fresh valise in the boot for those last-minute trips. He has his business callers presented with their libation of choice as soon as they are seated in his study, whereas the lady of the house prefers to call for tea service. The lady also wishes the packages from her excursions delivered with inconspicuous haste to her quarters. You are aware that her purchases are none of your concern, although her husband appreciates a discreet heads-up as to the extent of the day’s expenditures.

Knowing such things made my father, even as a young man, a much sought after commodity.

Jacob Housewright obtained his first position through something of a ruse. This was during Josiah’s employer’s tenure in the capital, and a business associate of the industrialist reported that his manservant had fallen ill and had been sent home to his family. Frantic, quite literally helpless, the business associate had asked the industrialist if he couldn’t make loan of one of his boys as a stopgap measure. You are familiar with, of course, the old maxim about good help, and this is particularly the case with exclusive and high-quality staff. My grandfather ran a tight operation, and had not been keen on giving up a valued hand for even an hour. Father, then only seventeen, and talented eavesdropper that he was, overheard his parents discussing the request. He volunteered himself for the position.

To put it mildly, Grandfather was less than sanguine about his son’s ambitions. Here, this young pup who couldn’t possibly know a goblet from a tumbler thought he would march into an important man’s home and assume responsibility for its efficient operation. And you should know that it has long been a Housewright doctrine that each generation’s work reflects on the generation preceding it. My grandfather wasn’t willing to risk the family reputation by sending someone whom he believed to be less than fully prepared into such a high-profile position. He told his son “no,” and that the business associate would just need to search for help elsewhere.

Father viewed this rebuff as only a temporary setback. While always professionally reticent—and appropriately so—my father could also take bold and direct action as was needed. Scouring the neighborhood where the business associate lived, Father visited each of the service establishments where persons of this standing might trade. Laundries, haberdashers, that sort of thing. By happenstance he stumbled across a tailor who had made for this gentleman some new dress shirts, and Father bluffed at having been sent to retrieve them. Costuming himself, then, in a manservant’s proper afternoon attire (white collared shirt, bow tie, dark short coat), he presented himself at the needy gentleman’s home.

“I’ve seen to your order of shirts, sir. Shall I place them in your wardrobe?”

I can picture my father standing at that man’s door, fair and handsome, back straight and tall. I see his new employer, momentarily startled, but quickly assuming that this fellow must be the replacement boy he’d been asking after. Things would have become quite frayed around the house since old Pompey had been sent back home, and while this sapling looked a little on the green side, he certainly made a nice appearance and spoke well for himself.

“Very well, then,” the older man would have said. He’d needed those new shirts desperately, had forgotten where old Pompey said they were being prepared. “Have one ready for the evening, by the way, with my summer jacket. We’ll be attending that garden party uptown. And bring me a brandy, if you would.”

I picture my father delivering that brandy (along with a neatly folded afternoon paper, of course).

“Thank you, uh . . . what’s your name?”

“Jacob, sir,” he would have replied, and, expecting no further conversation from a gentleman settling in for his afternoon’s consideration of the news, my father would have set about getting his new place of responsibility in an order that made sense to him.

As it happened, Father’s new employer’s requirements were much less taxing than those at the house my grandfather ran. The old gentleman operated from a smaller townhouse just northwest of Dupont Circle, in an area that had begun to be populated by the embassies of minor and obscure nations. He was in Washington to help guide the meanderings of a hapless and dull-witted son who had somehow gotten himself elected to the House of Representatives. Days for my father would be generally idle, tending to the usual trivia that one sees to in a small home, and in the evenings my father would dress his employer and deliver him to his son the congressman’s house, or to a party they would both be attending. This gentleman knew Washington from his own tenure in Congress, during which he had spearheaded expansion of the railroads and the acquisition of western lands. A longtime widower, he now lived comfortably on the investments that had benefited from his legislative largesse.

Too young to be comfortable visiting with the other more seasoned servants, my father would often spend these evenings positioned where he could listen unobtrusively to the conversations of the congressman and his father. He remembered to me that one almost never heard the son speaking at these affairs, that the father held forth at all times and on all matters, now and again throwing in his son’s direction openings that allowed the younger man to demonstrate his sagacity either by adding to the discourse some dutifully memorized fact or by, at the very least, agreeing enthusiastically with his father’s brilliance. I may or may not surprise you by revealing that this rather dunderheaded young man would go on to become one of our nation’s most distinguished and beloved political figures.

You have also noted by this point the care I have taken not to reveal the names of these individuals. You may think me unnecessarily coy or mysterious, but please understand that that is not my intention. Understand that the Housewrights have always been discreet; part of that long tradition of retainers who could be counted on not to repeat their employer’s business in the street, a commitment that I believe extends to the grave (and perhaps beyond, depending, of course, on what the circumstances on the other side might be). And, yes, I am aware that if you happen to be among those who have traveled in these same circles, you more than likely will recognize in these stories certain individuals by their attributes, by the thinly disguised details of their personal lives, and so be it. There are some things about which I feel compelled to have my say, and so I have had to relax my own discretion by a degree or two. Father would understand and forgive, I am sure, just as I have always tried myself to do the same.

Toward the end of his son’s third term, my father’s first employer told him that he had no desire to spend his final days in this “fetid swamp,” and that he had therefore decided to return home, allowing his son to sink or swim as he would. The old man did everything short of kidnapping “his Jake” in order to keep him in his employ, and Father, I know, gave staying with this household serious consideration. If you’ve never been in service, you perhaps wouldn’t understand the attachment we make to those who employ us. At the risk of indelicacy I will say that a gentleman’s home assistant has the most intimate contact with the man he works for, personally handling every garment, both clean and soiled, preparing baths, administering medicine and comfort as would be required. My father knew that this failing creature both needed and depended on him. Over time, a gentleman and his retinue become something like a hand and a much-used glove, each molded to the other’s peculiar geography. Across five years Jacob had learned this man’s habits and predilections, and his employer had learned how best to make use of Father’s many strengths. A relationship of this quality would not be easily replaced, on either man’s part.

So it was with a good deal of personal regret that Father made the choice to stay in Washington, though I’d be remiss in not reporting two other factors that weighed heavily in his decision making.

Even as the household that Grandfather Josiah ran continued to operate in the efficiently sharp manner one would expect, considering who was at the helm, it seems that the lives of my uncle and my aunts were taking turns toward the unfortunate. While my fa...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherCrown

- Publication date2004

- ISBN 10 0767915690

- ISBN 13 9780767915694

- BindingPaperback

- LanguageEnglish

- Edition number1

- Number of pages384

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Search results for The Full Matilda: A Novel

The Full Matilda: A Novel

Seller: Wonder Book, Frederick, MD, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Good condition. A copy that has been read but remains intact. May contain markings such as bookplates, stamps, limited notes and highlighting, or a few light stains. Seller Inventory # J12B-02086

Quantity: 2 available

The Full Matilda: A Novel

Seller: BookHolders, Towson, MD, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. [ No Hassle 30 Day Returns ][ Ships Daily ] [ Underlining/Highlighting: NONE ] [ Writing: NONE ] [ Edition: Reprint ] Publisher: Harlem Moon Pub Date: 5/11/2004 Binding: Paperback Pages: 384 Reprint edition. Seller Inventory # 6769475

Quantity: 1 available

The Full Matilda : A Novel

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 863772-6

Quantity: 2 available

The Full Matilda : A Novel

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Seller Inventory # 14897292-6

Quantity: 1 available

The Full Matilda: A Novel

Seller: HPB Inc., Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

paperback. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority!. Seller Inventory # S_416820239

Quantity: 1 available

The Full Matilda: A Novel

Seller: Half Price Books Inc., Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

paperback. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority!. Seller Inventory # S_360410378

Quantity: 1 available

The Full Matilda: A Novel

Seller: The Maryland Book Bank, Baltimore, MD, U.S.A.

paperback. Condition: Very Good. First Edition. Used - Very Good. Seller Inventory # 7-R-2-0215

Quantity: 1 available

The Full Matilda: A Novel

Seller: medimops, Berlin, Germany

Condition: good. Befriedigend/Good: Durchschnittlich erhaltenes Buch bzw. Schutzumschlag mit Gebrauchsspuren, aber vollstšndigen Seiten. / Describes the average WORN book or dust jacket that has all the pages present. Seller Inventory # M00767915690-G

Quantity: 1 available

The Full Matilda

Seller: The Book House, Inc. - St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.

Trade Paperback. Condition: Good. Good trade paperback, slight wear. Signed and inscribed by author on title page. Signed. Seller Inventory # 210502-RD70

Quantity: 1 available

The Full Matilda : A Novel

Seller: Robinson Street Books, IOBA, Binghamton, NY, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Used; Good. Prompt Shipment, in Boxes, Tracking First Editions are First Printings. . Contemporary FictionGood used library book. Clean print. Seller Inventory # ware682JD055

Quantity: 1 available