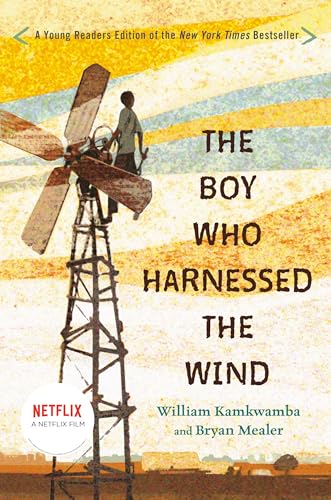

Items related to The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind: Young Readers Edition

Synopsis

Now a Netflix film starring and directed by Chiwetel Ejiofor, this is a gripping memoir of survival and perseverance about the heroic young inventor who brought electricity to his Malawian village.

When a terrible drought struck William Kamkwamba's tiny village in Malawi, his family lost all of the season's crops, leaving them with nothing to eat and nothing to sell. William began to explore science books in his village library, looking for a solution. There, he came up with the idea that would change his family's life forever: he could build a windmill. Made out of scrap metal and old bicycle parts, William's windmill brought electricity to his home and helped his family pump the water they needed to farm the land.

Retold for a younger audience, this exciting memoir shows how, even in a desperate situation, one boy's brilliant idea can light up the world. Complete with photographs, illustrations, and an epilogue that will bring readers up to date on William's story, this is the perfect edition to read and share with the whole family.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

William Kamkwamba recently graduated from Dartmouth College. The original version of his memoir The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind was a New York Times Bestseller and a Publishers Weekly Best Book of the Year. He divides his time between Malawi and San Francisco, California.

Bryan Mealer is the author of Muck City and the New York Times bestseller The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind, which he wrote with William Kamkwamba. Since publication, the book has received many honors and has been translated into over a dozen languages. Mealer is also the author of All Things Must Fight to Live, which chronicled his years covering the war in the Democratic Republic of Congo for Harper's and the Associated Press. His forthcoming book, The Kings of Big Spring, a multi-generational saga about his family in West Texas, will be published by Flatiron Books in early 2018. He and his family live in Austin.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

PROLOGUE

The machine was ready. After so many months of preparation, the work was finally complete: The motor and blades were bolted and secured, the chain was taut and heavy with grease, and the tower stood steady on its legs. The muscles in my back and arms had grown as hard as green fruit from all the pulling and lifting. And although I’d barely slept the night before, I’d never felt so awake. My invention was complete. It appeared exactly as I’d seen it in my dreams.

News of my work had spread far and wide, and now people began to arrive. The traders in the market had watched it rise from a distance and they’d closed up their shops, while the truck drivers left their vehicles on the road. They’d crossed the valley toward my home, and now they gathered under the machine, looking up in wonder. I recognized their faces. These same men had teased me from the beginning, and still they whispered, even laughed.

Let them, I thought. It was time.

I pulled myself onto the tower’s first rung and began to climb. The soft wood groaned under my weight as I reached the top, where I stood level with my creation. Its steel bones were welded and bent, and its plastic arms were blackened from fire.

I admired its other pieces: the bottle-cap washers, rusted tractor parts, and the old bicycle frame. Each one told its own story of discovery. Each piece had been lost and then found in a time of fear and hunger and pain. Together now, we were all being reborn.

In one hand I clutched a small reed that held a tiny lightbulb. I now connected it to a pair of wires that dangled from the machine, then prepared for the final step. Down below, the crowd cackled like hens.

“Quiet, everyone,” someone said. “Let’s see how crazy this boy really is.”

Just then a strong gust of wind whistled through the rungs and pushed me into the tower. Reaching over, I unlocked the machine’s spinning wheel and watched it begin to turn. Slowly at first, then faster and faster, until the whole tower rocked back and forth. My knees turned to jelly, but I held on.

I pleaded in silence: Don’t let me down.

Then I gripped the reed and wires and waited for the miracle of electricity. Finally, it came, a tiny flicker in my palm, and then a magnificent glow. The crowd gasped, and the children pushed for a better look.

“It’s true!” someone said.

“Yes,” said another. “The boy has done it. He has made electric wind!”

CHAPTER ONE

My name is William Kamkwamba, and to understand the story I’m about to tell, you must first understand the country that raised me. Malawi is a tiny nation in southeastern Africa. On a map, it appears like a flatworm burrowing its way through Zambia, Mozambique, and Tanzania, looking for a little room. Malawi is often called “The Warm Heart of Africa,” which says nothing about its location, but everything about the people who call it home. The Kamkwambas hail from the center of the country, from a tiny village called Masitala, located on the outskirts of the town of Wimbe.

You might be wondering what an African village looks like. Well, ours consists of about ten houses, each one made of mud bricks and painted white. For most of my life, our roofs were made from long grasses that we picked near the swamps, or dambos in our Chichewa language. The grasses kept us cool in the hot months, but during the cold nights of winter, the frost crept into our bones and we slept under an extra pile of blankets.

Every house in Masitala belongs to my large extended family of aunts and uncles and cousins. In our house, there was me, my mother and father, and my six sisters, along with some goats and guinea fowl, and a few chickens.

When people hear I’m the only boy among six girls, they often say, “Eh, bambo”—which is like saying “Hey, man”—“so sorry for you!” And it’s true. The downside to having only sisters is that I often got bullied in school since I had no older brothers to protect me. And my sisters were always messing with my things—especially my tools and inventions—giving me no privacy.

Whenever I asked my parents, “Why do we have so many girls in the first place?” I always got the same answer: “Because the baby store was all out of boys.” But as you’ll see in this story, my sisters are actually pretty great. And when you live on a farm, you need all of the help you can get.

My family grew maize, which is another word for white corn. In our language, we lovingly referred to it as chimanga. And growing chimanga required all hands. Every planting season, my sisters and I would wake up before dawn to hoe the weeds, dig our careful rows, then push the seeds gently into the soft soil. When it came time to harvest, we were busy again.

Most families in Malawi are farmers. We live our entire lives out in the countryside, far away from cities, where we can tend our fields and raise our animals. Where we live, there are no computers or video games, very few televisions, and for most of my life, we didn’t have electricity—just oil lamps that spewed smoke and coated our lungs with soot.

Farmers here have always been poor, and not many can afford an education. Seeing a doctor is also difficult, since most of us don’t own cars. From the time we’re born, we’re given a life with very few options. Because of this poverty and lack of knowledge, Malawians found help wherever we could.

Many of us turned to magic—which is how my story begins.

You see, before I discovered the miracles of science, I believed that magic ruled the world. Not magician magic, like pulling rabbits out of hats or sawing ladies in half, the sort of thing you see on television. It was an invisible kind of magic, one that surrounded us like the air we breathe.

In Malawi, magic came in many forms—the most common being the witch doctor whom we called sing’anga. The wizards were mysterious people. Some appeared in public, usually in the market on Sundays, sitting on blankets spread with bones, spices, and powders that claimed to cure everything from dandruff to cancer. Poor people walked many miles to visit these men, since they didn’t have money for real doctors. This led to problems, especially if a person was truly sick.

Take diarrhea, for example. Diarrhea is a common ailment in the countryside that comes from drinking dirty water, and if left untreated, it can lead to dehydration. Every year, too many children die from something that’s easily cured by a regimen of fluids and simple antibiotics. But without money or faith in modern medicine, the villager takes his chances with the sing’anga’s crude diagnosis:

“Oh, I know what’s wrong,” the wizard says. “You have a snail.”

“A snail?”

“I’m almost positive. We must remove it at once!”

The wizard goes into his bag of roots, powders, and bones, and pulls out a lightbulb.

“Lift up your shirt,” he says.

Without plugging the bulb into anything, he moves it slowly across the person’s stomach, as if to illuminate something only he can detect.

“There it is! Can you see the snail moving?”

“Oh yes, I think I can see it. Yes, there it is!”

The wizard returns to his bag for some magic potion, which he splashes across the belly.

“All better?” he asks.

“Yes, I think the snail is gone. I don’t feel it moving.”

“Good. That will be three thousand kwacha.”

For a little extra money, the sing’anga can cast curses on your enemies—to deliver floods to their fields, hyenas to their chicken house, or terror and tragedy into their homes. This is what happened to me when I was six years old—or at least I thought it did.

I was playing in front of my house when a group of boys walked past carrying a giant sack. They worked for a nearby farmer tending his cows. That morning, as they were moving the herd from one pasture to another, they discovered the sack lying on the road. Looking inside, they saw that it was filled with bubble gum. Can you imagine such a treasure? I can’t begin to tell you how much I loved bubble gum!

Now, as they walked past, one of them spotted me playing in a puddle.

“Should we give some to this boy?” he asked.

I didn’t move or say a word. A bit of mud dripped from my hair.

“Eh, why not,” his friend said. “He looks kind of pathetic.”

The boy reached into his bag and produced a rainbow of gumballs—one of every color—and dropped them into my hands. By the time the boys disappeared, I’d shoved every one into my mouth. The sweet juices dribbled down my chin and stained my shirt.

Little did I know, but the bubble gum belonged to a local trader, who stopped by our house the next day. He told my father how the bag had dropped from his bicycle as he was leaving the market. By the time he circled back to look for it, the bag was gone. The people in the next village told him about the herd of boys. Now he wanted revenge.

“I’ve gone to see the sing’anga,” he told my father. “And whoever ate that bubble gum will be sorry.”

Suddenly I was terrified. I’d heard what the sing’anga could do to a person. In addition to delivering death and disease, the wizards controlled armies of witches who could kidnap me during the night and shrink me into a worm! I’d even heard about them turning children into stones, leaving them to suffer an eternity in silence.

Already, I could feel the sing’anga watching me, plotting his evil. With my heart racing, I ran into the forest behind my house to try to escape, but it was no use. I felt the strange warmth of his magic eye shining through the trees. He had me. At any moment, I would emerge from the forest as a beetle, or a trembling mouse to be eaten by the hawks. Knowing my time was short, I hurried home to where my father was plucking a pile of maize and tumbled into his lap.

“It was me!” I shouted, tears running down my cheeks. “I ate the stolen gum. I don’t want to die, Papa. Please don’t let them take me.”

My father looked at me for a second and shook his head. “It was you, eh?” he said, then kind of smiled.

Didn’t he realize I was in trouble?

“Well,” he said, and his knees popped as he rose from his chair. My father was a big man. “Don’t worry, William. I’ll find the trader and explain. I’m sure we can work something out.”

That afternoon, my father walked five miles to the trader’s house and told him what had happened. And even though I’d only eaten a few of the gumballs, he paid the man for the entire bag, which was nearly all the money we possessed. That evening after supper, my life having been saved, I asked my father if he truly believed I was in trouble. He became very serious.

“Oh yes, we were just in time,” he said, then started laughing so hard his chair began to squeak. “William, who knows what was in store for you?”

My fear of wizards and magic only grew worse whenever Grandpa told stories. If you saw my grandpa, you might think he was a kind of wizard himself. He was so old that he couldn’t remember the year he’d been born. So cracked and wrinkled that his hands and feet looked as if they were chiseled from stone. And his clothes! Grandpa insisted on wearing the same tattered coat and trousers every day. Whenever he emerged from the forest, puffing on his hand-rolled cigar, you’d think one of the trees had grown legs and started walking.

It was Grandpa who told me the greatest story about magic I’d ever heard. Long ago, before the giant maize and tobacco farms came along and cleared away our great forests, when a person could lose track of the sun inside the trees, the land was rich with antelope, zebra, and wildebeest—also lions, hippos, and leopards. Grandpa was a famous hunter, so good with his bow and arrow that it became his duty to protect his village and provide its meat.

One day while Grandpa was out hunting, he came across a man who’d been killed by a poisonous pit viper. He alerted the nearest village, and soon after, they returned with their witch doctor.

The sing’anga took one look at the dead man, then reached into his bag and tossed some medicines into the trees. Seconds later, the earth began to move as hundreds of vipers slithered out of the shadows and gathered around the corpse, hypnotized by the spell. The wizard then stood on the dead man’s chest and drank a cup of potion, which seemed to flow through his feet and into the lifeless body. Then, to Grandpa’s amazement, the dead man’s fingers began to move and he sat up. Together, he and the wizard inspected the fangs of each snake, looking for the one that had bitten him.

“Believe it,” Grandpa told me. “I saw this with my own eyes.”

I certainly believed it, along with every other story about witches and things unexplained. Whenever I went down the dark trails alone, my imagination spun wild.

What scared me most were the Gule Wamkulu, the magical dancers that lived in the murky shadows of the forest. They sometimes appeared in the daylight, performing in tribal ceremonies when we Chewa boys became men. They were not real people, we were told, but spirits of our dead ancestors sent to roam the earth. Their appearance was ghastly: Each had the face and skin of animals and some walked on stilts to appear taller. Once, I saw one scurry backward up a pole like a spider. And when they danced, it was as if one thousand men were inside their bodies, each moving in the opposite direction.

When the Gule Wamkulu weren’t performing, they traveled the forests and dambos looking for young boys to take back to the graveyards. What happened to you there, I never wanted to know. Whenever I saw one, even at a ceremony, I dropped everything and ran. Once, when I was very young, a magic dancer suddenly appeared in our courtyard. His head was wrapped in a flour sack, but underneath was the long nose of an elephant and a gaping hole for a mouth. My mother and father were in the fields, so my sisters and I ran for the bush, where we watched the dancer snatch our favorite chicken.

Unlike the Gule Wamkulu or sing’anga in the market, most witches and wizards never revealed their identity. In the places where they practiced their magic, mystery abounded like strange weather. In the nearby town of Ntchisi, men with bald heads, standing as tall as trees, walked the roads at night. Ghost trucks traveled back and forth, approaching fast with their headlights flashing and engines revving loud. Yet when the lights finally passed, there was no truck attached. In one of the neighboring villages, I heard about a man who’d been shrunk so small by a wizard that his wife kept him in a Coke bottle.

In addition to casting spells for curses, the sing’anga often battled one another. At night, they piled aboard their planes and prowled the skies, looking for children to kidnap as soldiers. The witch planes could be anything: a wooden bowl, a broom, a simple hat. And each was capable of traveling great distances—Malawi to New York, for example—in a single minute. Children were used as guinea pigs and sent to test the powers of rival wizards. Other nights, they’d visit camps of other witch children for games of mystical soccer, where the balls wer...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherRocky Pond Books

- Publication date2015

- ISBN 10 0803740808

- ISBN 13 9780803740808

- BindingHardcover

- LanguageEnglish

- Number of pages304

- IllustratorHymas Anna

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.49

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Hymas, Anna (illustrator). Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00074838366

Quantity: 5 available

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Hymas, Anna (illustrator). Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00078100817

Quantity: 2 available

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind: Young Readers Edition

Seller: Goodwill, Brooklyn Park, MN, U.S.A.

Condition: VeryGood. Hymas, Anna (illustrator). Item has stickers or notes attached to cover and/or pages that have not been removed to prevent further damage. Seller Inventory # 2Y6RVK00528R_ns

Quantity: 1 available

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind: Young Readers Edition

Seller: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Fair. No Jacket. Hymas, Anna (illustrator). Former library book; Readable copy. Pages may have considerable notes/highlighting. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.04. Seller Inventory # G0803740808I5N10

Quantity: 3 available

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind: Young Readers Edition

Seller: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Fair. No Jacket. Hymas, Anna (illustrator). Missing dust jacket; Readable copy. Pages may have considerable notes/highlighting. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.04. Seller Inventory # G0803740808I5N01

Quantity: 1 available

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind: Young Readers Edition

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Fair. No Jacket. Hymas, Anna (illustrator). Readable copy. Pages may have considerable notes/highlighting. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.04. Seller Inventory # G0803740808I5N00

Quantity: 1 available

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind: Young Readers Edition

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Fair. No Jacket. Hymas, Anna (illustrator). Missing dust jacket; Readable copy. Pages may have considerable notes/highlighting. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.04. Seller Inventory # G0803740808I5N01

Quantity: 1 available

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind: Young Readers Edition

Seller: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Hymas, Anna (illustrator). Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.04. Seller Inventory # G0803740808I3N00

Quantity: 1 available

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind: Young Readers Edition

Seller: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. Hymas, Anna (illustrator). Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.04. Seller Inventory # G0803740808I4N10

Quantity: 2 available

The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind: Young Readers Edition

Seller: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Hymas, Anna (illustrator). Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.04. Seller Inventory # G0803740808I3N10

Quantity: 2 available