Synopsis

With lacerating prose and exhilarating wit, Michaels takes on the many manifestations of our devotion to diversity, from companies apologizing for slavery, to a college president explaining why there aren't more women math professors, to the codes of conduct in the new "humane corporations." Looking at the books we read, the TV shows we watch, and the lawsuits we bring, Michaels shows that diversity has become everyone's sacred cow precisely because it offers a false vision of social justice, one that conveniently costs us nothing. The Trouble with Diversity urges us to start thinking about real justice, about equality instead of diversity. Attacking both the right and the left, it will be the most controversial political book of the year.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Reviews

In this cogent jeremiad, which is certain to be controversial, Michaels diagnoses America's love of diversity as one of our greatest problems. Not only does it reinforce ideas of racial essentialism that it claims to repudiate; it obscures the crevasse between rich and poor. Michaels, a scholar of American literature, suggests that the growth of economic inequality over the past few decades is the result of a deeply ingrained and unchallenged class structure. Scrutinizing current events and religion, he argues that our fixation with the "phantasm" of race promotes identity over ideology, and he rejects the idea that meritocracy prevails in America's elite universities. A believer in the power of progressive politics, he calls for a debate in which class, rather than identity, would be at the fore.

Copyright © 2006 Click here to subscribe to The New Yorker

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

Other Popular Editions of the Same Title

Search results for The Trouble with Diversity: How We Learned to Love...

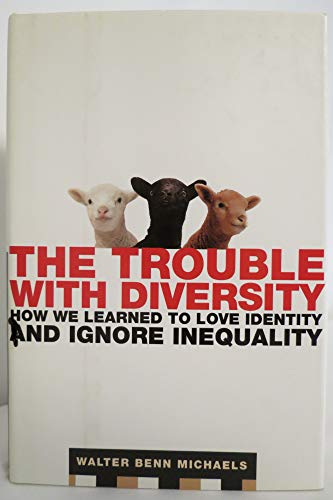

The Trouble with Diversity: How We Learned to Love Identity and Ignore Inequality

Seller: World of Books (was SecondSale), Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00087018964

The Trouble with Diversity: How We Learned to Love Identity and Ignore Inequality

Seller: ZBK Books, Carlstadt, NJ, U.S.A.

Condition: good. Fast & Free Shipping â" Good condition with a solid cover and clean pages. Shows normal signs of use such as light wear or a few marks highlighting, but overall a well-maintained copy ready to enjoy. Supplemental items like CDs or access codes may not be included. Seller Inventory # ZWV.080507841X.G

The Trouble with Diversity : How We Learned to Love Identity and Ignore Inequality

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # GRP88819606

The Trouble with Diversity : How We Learned to Love Identity and Ignore Inequality

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Seller Inventory # 4722183-75

The Trouble with Diversity : How We Learned to Love Identity and Ignore Inequality

Seller: Better World Books: West, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # GRP88819606

The Trouble with Diversity: How We Learned to Love Identity and Ignore Inequality

Seller: Zoom Books East, Glendale Heights, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: good. Book is in good condition and may include underlining highlighting and minimal wear. The book can also include "From the library of" labels. May not contain miscellaneous items toys, dvds, etc. . We offer 100% money back guarantee and 24 7 customer service. Seller Inventory # ZEV.080507841X.G

The Trouble with Diversity: How We Learned to Love Identity and Ignore Inequality

Seller: BooksRun, Philadelphia, PA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. First Edition. With dust jacket. It's a preowned item in good condition and includes all the pages. It may have some general signs of wear and tear, such as markings, highlighting, slight damage to the cover, minimal wear to the binding, etc., but they will not affect the overall reading experience. Seller Inventory # 080507841X-11-1-29

The Trouble with Diversity: How We Learned to Love Identity and Ignore Inequality

Seller: HPB-Ruby, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Very Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used books may not include companion materials, and may have some shelf wear or limited writing. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Seller Inventory # S_380226375

The Trouble with Diversity: How We Learned to Love Identity and Ignore Inequality

Seller: HPB-Red, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Good. Connecting readers with great books since 1972! Used textbooks may not include companion materials such as access codes, etc. May have some wear or writing/highlighting. We ship orders daily and Customer Service is our top priority! Seller Inventory # S_382225808

The Trouble with Diversity: How We Learned to Love Identity and Ignore Inequality

Seller: Red's Corner LLC, Tucker, GA, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: New. All orders ship by next business day! This is a new book. We are a small company and very thankful for your business! Seller Inventory # 4CNZE9000DQK