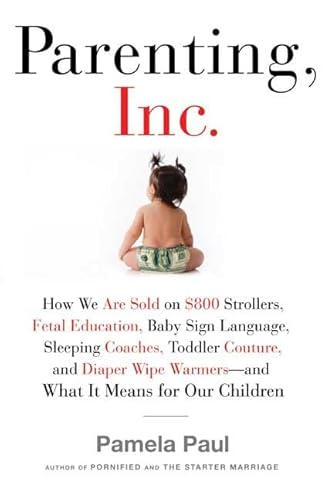

Items related to Parenting, Inc.: How the Billion-Dollar Baby Business...

Parenting, Inc.: How the Billion-Dollar Baby Business Has Changed the Way We Raise Our Children - Hardcover

Parenting coaches, ergonomic strollers, music classes, sleep consultants, luxury diaper creams, a never-ending rotation of DVDs that will make a baby smarter, socially adept, and bilingual before age three. Time-strapped, anxious parents hoping to provide the best for their baby are the perfect mark for the “parenting” industry.

In Parenting, Inc., Pamela Paul investigates the whirligig of marketing hype, peer pressure, and easy consumerism that spins parents into purchasing overpriced products and raising overprotected, overstimulated, and over-provided-for children. Paul shows how the parenting industry has persuaded parents that they cannot trust their children’s health, happiness, and success to themselves. She offers a behind-the-scenes look at the baby business so that any parent can decode the claims—and discover shockingly unuseful products and surprisingly effective services. And she interviews educators, psychologists, and parents to reveal why the best thing for a baby is to break the cycle of self-recrimination and indulgence that feeds into overspending.

Paul’s book leads the way for every parent who wants to escape the spiral of fear, guilt, competition, and consumption that characterizes modern American parenthood.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Prologue

When she was seven months old, my husband and I seriously considered enrolling our daughter, Beatrice, who has no hearing impairment, in baby sign language class. Oh, we did have some initial doubts: If Beatrice was busy learning how to fold and pleat her fingers into signing gestures, wouldn’t that take time and attention away from learning to speak? Wouldn’t being able to communicate through signs remove any incentive to talk? But our misgivings were brushed aside by the baby signing professionals and their acolytes. Signing is like crawling, they explained. Just as crawling gives your baby that taste of movement that motivates her to walk, signing inspires the voiceless communicator to learn how to verbalize. Not only do signing babies speak earlier, but research indicates they have higher IQ scores, by an average of twelve points, at age eight, they pointed out.

Baby signing—for babies who can hear perfectly well—had become so popular that we also felt prodded by a competitive impetus: Everyone else seemed to be signing their children up. Our friends Paul and Ericka had a daughter who signed; she waved and poked her chubby hands about whenever she wanted to speak her mind. A genius! Shouldn’t Beatrice have the same advantage? Any parent can understand why we were tempted. We all want to provide our children with every opportunity and are eager to get a sense of what’s going on inside our preverbal babies’ minds.

Still, the classes were expensive. Plus, it would take time away from work in order for me to commute to wherever it was that baby signers convened, surely not in my neighborhood, where most parents struggle to afford quality day care. As an alternative, we could allocate precious weekend time to the classes, allowing both my husband and me to attend, but even the thought of adding one more thing to our pittance of “time off” made me weary. Either way, on top of everything, we would have to teach the babysitter how to sign too, and when would we ever find the time to do that? Wouldn’t Beatrice get frustrated if her caretaker didn’t understand what she was trying to “say”?

On the other hand, there were incentives to get Beatrice started on language skills immediately. Getting into preschool in New York City is cutthroat, as it is increasingly around the country. Many applications include ample space in which to list the “classes” two-year-olds have attended before they’ve even enrolled in their first school. How could I forgo an activity that might provide the decisive advantage? I would kick myself ten times over for my neglect. If Beatrice proved to be an “accelerated learner,” we could potentially enroll her at a magnet public school later on, rather than a private school, either one a necessity since our neighborhood is bereft of good public schools. This would in turn free up money for our other children’s education, in case they didn’t get into a good public school.

If Beatrice didn’t “measure up,” the tuition for private nursery school alone would run up to $25,000 a year; if we had three kids, the price of education would eventually eat up a six-figure income each year. Suddenly, it seemed that if Beatrice didn’t baby-sign, we wouldn’t have enough money to afford three kids, something my husband and I, both products of large families, really want.

Or so my snowballing logic went. Like all parents, I am confronted every day with complex spending decisions for my children. And I can drive myself nuts trying to weigh the pros, cons, and costs of the overwhelming options. No matter what I do, someone else seems to be doing enviably more or improbably less, and either way, their child and family seem all the better for it.

But with the sign language conundrum, I had the benefit of finding an answer through my job as a journalist. While researching a story on cognitive development for Time magazine, I came upon a comprehensive review of studies on baby signing. Contrary to what I had been led to believe by the baby signers’ websites and brochures, the evidence is all over the place. Some studies even showed signing babies to be worse off than their non-gesturing counterparts. After an interview with one of the review’s authors, my husband and I decided to bypass the whole thing. (For the record, our daughter speaks just fine and, at age three, gesticulates in her own, invented ways.)

Making these kinds of decisions—choosing what not to do or buy for our baby—isn’t easy. Saying no runs counter to all our instincts as parents and to everything the parenting culture tells us. Aren’t we supposed to do everything we possibly can for our children? Doesn’t this frequently mean sparing no expense? Many parents already feel tremendous guilt for working long hours and spending less time than they would like with their children. Now add to that a layer of guilt for not spending as much money on them as we could. With every no, you can hear the judgments and recriminations, be they imagined or actual: What are you going to do with that money instead? Go out to dinner more often? Buy yourself more clothes? Sock money away in your retirement fund—before taking care of your own children? We are pressured to spend by the cautions of experts, the advice of parenting pros, and the endless and frightfully persuasive marketers proclaiming that certain goods, services, activities, and environments ensure a happier, smarter, healthier, and safer child. A more emotionally secure and socially successful child. A better baby.

at the time when we feel most disabled as decision makers—by experts, advertisements, product overload, our own niggling doubts—the need to make reasoned decisions is greater than ever. Raising kids today costs a fortune. Rather than plot family size based on any number of factors—one’s ideal conception of family, the kind of life one wants to lead, the disruption that pregnancy and child rearing might bring to one’s career, the terrifying thought of traveling to visit grandparents with a full brood in tow—often the decision about whether to have one child, or more, pivots on the question: Can we afford it?

This just seems wrong. How can money be what makes or breaks such a personal decision? “Why can’t we just have a kid the way our parents did in the seventies?” asked a friend I’ve known since my early twenties—I’ll call her Ava. She wasn’t referring to giving birth on a leftover hippie commune, nor did she especially hanker for a child outfitted in an orange velour ensemble and bowl haircut. She simply wanted to be able to afford having a baby, perhaps two, as so many of our parents did, almost unthinkingly, just a few decades ago. Whether or not to have kids and how many were choices that once could be made without poring over Quicken and breaking into a premature sweat about college costs. Sure, everyone has always complained that “kids are expensive,” but when people said it in the 1970s, they often meant that in a period of rapid inflation sugar cereals cost twice as much as cornflakes and store-bought Halloween costumes were overpriced. Many parents didn’t even worry about college tuition until their kids were in junior high, and the money needed to cover it today would barely pay for preschool, even adjusted for inflation.

Despite oil lines and inflation, raising a child in the 1970s was cheap. Even during the supposed heyday of family life, in 1958, parents spent about half what they spend now, the equivalent of $5,470 on goods and services ($800 in 1958 dollars) during a baby’s first year. The major cost creep can be dated to the 1980s, when the baby boomers entered parenthood, and prices continued to spiral upward during the 1990s as the boomers’ spending on their kids hit its peak. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture (which, of all government bureaucracies, is the one that tracks these things), the cost of raising a child born in 2006 from birth to the age of seventeen is $143,790 for parents in the lowest income group (households earning less than $44,500 a year) and $289,390 for parents with the highest incomes (those earning more than $74,900 and an average income of $112,200).

These numbers don’t even give a realistic sense of just how much children cost. Experts agree that though the government estimates try to account for housing, food, transportation, clothing, health care, childcare, education, and miscellaneous goods and services, the Department of Agriculture lowballs these costs by a long shot. For example, the government expects parents in the wealthiest group to spend $2,850 on childcare and education during the first two years of a baby’s life,* while the National Association of Child Care Resource and Referral Agencies, a network of more than 805 childcare resource and referral centers, reports that the average cost of childcare for an infant—no matter how much the parents earn—ranges from $3,803 to $13,480 a year.

Costs spiral much, much higher in major urban areas. According to a 2006 report in USA Today, the cost of childcare is leading parents nationwide to make major lifestyle adjustments: relocating, changing jobs, and selling homes. One Boston couple, the husband a software support engineer, the wife in communications, had to move and buy a new house in an area where they could find day care for under $850 because the $1,500 to $2,000 monthly price tag where they had been living in Boston was unaffordable. “We went into shock,” the mother complained. “That’s like a second mortgage.” In many cities, nannies charge between $400 and $750 a week, depending on experience and skills (licensed drivers, for example, earn more), and they typically charge $50 a week for each additional offspring. In New York or San Francisco, it’s tough to find a caregiver who will accept less than $500 for a forty-hour week (which doesn’t allow much time for a parent’s commute or overtime). That means $26,000 a year—not $2,850. And that’s if you’re paying your help illegally. To hire someone on the books costs an additional $6,000 or more annually, once you count taxes, benefits, and insurance. When many of today’s parents were growing up, live-in help was within the reach of upper-middle-class families. Now such arrangements are exclusive to the truly wealthy, though substantially more families today require the income of two working parents and often need near-around-the-clock childcare and household maintenance to make such work arrangements possible.

In addition to what parents have to pay out of pocket, there are the amounts we are supposed to set aside in those savings accounts for college. Adding government figures for middle-income families to estimates from the College Board, it takes about $500,000 to raise a child from birth through college, assuming the child goes to a public university. If she gets into the Ivy League, parents can bank on a tab of $635,000—not factoring in inflation.

Most of us are already behind. A 2006 poll of 2,239 parents found that although 79 percent of parents who expected their child to attend college also expected to have to pay for some or all of it, more than half had barely gotten started: 26 percent had saved less than $5,000 and 32 percent had not saved anything, despite the fact that personal financial advisers suggest putting aside a minimum of $1,000 a month for each child, starting at birth. If you’ve got two kids and need to put aside $2,000 every month, you may as well own two homes.

This sounds bad enough, yet these numbers still don’t tell the full story.

For one thing, the cost of raising children is rising far faster than our earnings. Estimated household income rose 24 percent during the past ten years, while the cost of raising a child rose 66 percent. That leaves even couples who make decent salaries belaboring the decision to have children based on the bottom line. Again and again, couples in their midtwenties to their midthirties say they don’t feel they can afford to have kids until at least one of them is making a six-figure salary.

Prospective parents are wrestling with this conundrum from the tony streets of Cambridge, Massachusetts, to the suburbs of Cleveland, Ohio. Recently married and well into her thirties, my friend Ava and her husband, Colin, wanted a baby, but their circumstances looked grim. Colin, a freelance writer, had no health benefits, and Ava had quit her job to pursue a more flexible, child-friendly self-employment. The little savings they had were earmarked for a down payment on a home, once the housing market cooled off. But having a baby seemed to require winning the Lotto or uncovering a lost millionaire aunt. This wasn’t a case of bemoaning the cost of a designer stroller. Ava and Colin—two college-educated professionals—actually thought that unless things changed, they would not be able to afford a family. Not a single child.

In the Wall Street Journal, columnist Terri Cullen publicly debated whether to have another child largely in terms of its financial impact: Since much of the baby gear used by her firstborn had been given away, Cullen was faced with the sticker shock of having to buy everything all over again. “With no shower for a second baby, we’d have to foot a bill that would amount to more than $5,000 ourselves.” Adding up the costs in childcare, education, baby food, and diapers, she realized:

All those new costs and years out of the workforce would cut into our ability to save—for retirement, college, an emergency, or otherwise. It’s a tradeoff [my husband] Gerry and I are reluctant to make. Ultimately, the arguments against another baby carried the day: I’d love to have one more child, but it doesn’t make sense for our family.

If a financial columnist at the Wall Street Journal can’t make it work, is it any wonder that two typical professionals in their thirties would be dismayed at the thought of supporting a child? Unnerved by the numbers but overcome with parental yearning, Ava and Colin went ahead with their procreation plan, and Ava got pregnant. Like so many other parents, they would just have to figure out how to afford it.

There were also the weighty, long-term problems to tackle. Would Ava’s salary cover the cost of childcare, let alone help provide for her family? Would they have to move farther away from their work opportunities in order to afford a house big enough for their family? Would they be able to take a vacation sometime in the next decade? Just how much would they have to give up in order to have a child? These questions of work arrangements, childcare, and housing are enough to send any parent into a state of despair. In a 2005 survey of 1,568 mothers by iVillage, 37 percent said they would need more than an additional $50,000 each year in order to significantly improve their quality of life with their children. When asked what they would change to become better mothers if time, money, and stress were not ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherTimes Books

- Publication date2008

- ISBN 10 0805082492

- ISBN 13 9780805082494

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages320

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Parenting, Inc.: How the Billion-Dollar Baby Business Has Changed the Way We Raise Our Children

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 0805082492-2-1

Parenting, Inc.: How the Billion-Dollar Baby Business Has Changed the Way We Raise Our Children

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0805082492

Parenting, Inc.: How the Billion-Dollar Baby Business Has Changed the Way We Raise Our Children

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0805082492

Parenting, Inc.: How the Billion-Dollar Baby Business Has Changed the Way We Raise Our Children Paul, Pamela

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Brand New Book %%%%. Seller Inventory # 50738

Parenting, Inc.: How the Billion-Dollar Baby Business Has Changed the Way We Raise Our Children

Book Description Condition: New. New! This book is in the same immaculate condition as when it was published. Seller Inventory # 353-0805082492-new

Parenting, Inc.: How We Are Sold on $800 Strollers, Fetal Education,, Baby Sign Language, Sleeping Coaches, Toddler Courture, and Diaper Wipe Warmers - and What It Means for Our Children Paul, Pamela

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.15. Seller Inventory # Q-0805082492