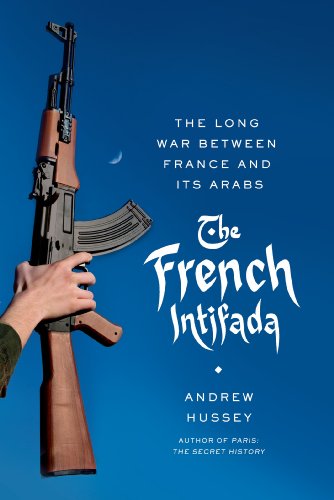

Items related to The French Intifada: The Long War Between France and...

A provocative rethinking of France's long relationship with the Arab world

To fully understand both the social and political pressures wracking contemporary France―and, indeed, all of Europe―as well as major events from the Arab Spring in the Middle East to the tensions in Mali, Andrew Hussey believes that we have to look beyond the confines of domestic horizons. As much as unemployment, economic stagnation, and social deprivation exacerbate the ongoing turmoil in the banlieues, the root of the problem lies elsewhere: in the continuing fallout from Europe's colonial era.

Combining a fascinating and compulsively readable mix of history, literature, and politics with his years of personal experience visiting the banlieues and countries across the Arab world, especially Algeria, Hussey attempts to make sense of the present situation. In the course of teasing out the myriad interconnections between past and present in Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, Beirut, and Western Europe, The French Intifada shows that the defining conflict of the twenty-first century will not be between Islam and the West but between two dramatically different experiences of the world―the colonizers and the colonized.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Murder in the Suburbs

A few short months after I had watched the riots at the Gare du Nord in 2007, on a cold evening in late November, I left my flat in southern Paris, took the metro to Saint-Denis, a suburb to the north of the city, and then a bus to an outlying council estate, or cité, called Villiers-le-Bel. The journey took little more than an hour but marked a sharp transition between two worlds: the calm centre of the city and the troubled banlieue.

‘ Banlieue’ is often mistranslated into English as ‘suburb’, but this conveys nothing of the fear and contempt that many middle-class French people invest in the word. In fact it first became widely used in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to describe the areas outside Paris where city-dwellers came and settled and built houses with gardens on the English model.

One of the paradoxes of life in the banlieue is that it was originally about hope and human dignity. To understand the banlieue you should think of central Paris as an oval-shaped haven or fortress, ringed by motorways – the boulevards périphériques (or le périph) – that mark the frontier between the city and the suburbs or banlieue. To live in the centre of Paris (commonly described as intra-muros, within the city walls, in language unchanged from the medieval period) is to be privileged: even if you are not particularly well off, you still have access to all the pleasures and amenities of a great metropolis. By contrast, the banlieue lies ‘out there’, on the other side of le périph. The area is extra-muros – outside the city walls. Transport systems here are limited and confusing. Maps make no sense. No one goes there unless he or she has to. It’s not uncommon for contemporary Parisians to talk about la banlieue in terms that make it seem as unknowable and terrifying as the forests that surrounded Paris in the Middle Ages.

The banlieues are made up of a population of more than a million immigrants, mostly but not exclusively from North and sub-Saharan Africa. As the population of central Paris has fallen in the early twenty-first century so the population of the banlieues is growing so fast that it will soon outnumber the two million or so inhabitants of central Paris. The banlieue is the very opposite of the bucolic sub-urban fantasy of the English imagination: for most French people these days it means a threat, a very urban form of decay, a place of racial tensions and of deadly if not random violence.

The day before I set off for Villiers-le-Bel, two teenagers of Arab origin had been killed at La Tolinette, one of the toughest parts of this tough neighbourhood, after their moped crashed into a police checkpoint. They had been on their way to do some rough motocross in an outlying field. No one in the area believed that this was an accident but rather a bavure – the kind of police cock-up that regularly ends with an innocent person dying or being injured. Within an hour gangs of youths pulled up their hoods, covered their faces with scarves and went on to the streets to hurl petrol bombs and stones at the police. A McDonald’s and a library were burned down. Streetlights were smashed or taken out so that the only light came from the flames of burning cars. The mayor of Villiers-le-Bel, Didier Vaillant, had tried to negotiate with the gangs but retreated under a hail of stones. A car dealership was set alight. By daybreak as many as seventy policemen had been injured. President Sarkozy, in Beijing, was alerted to the fact that a small but significant part of French territory was beyond control.

By the time I arrived in the banlieue the next day, the scene was set for another confrontation. ‘See, they treat us like fucking bougnoules,’ said Ikram, a young man of Moroccan origin who lived nearby, pointing at the police lines that were blocking access to certain areas. Bougnoule is a racist French term for Arabs that is as offensive as ‘nigger’ and dates back to the Algerian War of Independence, 1954–1962, when the French military used torture and terror against Algerian insurgents. The term bavure, meaning a police fuck-up, also comes from the same period. (The most infamous bavure was the so-called Battle of Paris, in October 1961, when a skirmish on the Pont de Neuilly between demonstrating Algerians and police led to a riot that ended with more than a hundred North Africans dead. Their bodies were thrown into the Seine by the police, under the orders of the Prefect of Police Maurice Papon, whose special brigades were known as ‘les BAVs’. Papon had previously been involved in the deportation of Jews during the German occupation of the early 1940s but was not prosecuted for his crimes until the 1990s.)

At around 5 p.m. it was getting dark and the mood and atmosphere changed in Villiers-le-Bel. Drinkers in the café where I was sitting began smoking harder. Civilians – that is to say, non-rioters – were hurriedly leaving the scene and then, quite without warning, the area was occupied entirely by the police and their opponents. I watched as the gangs moved in predatory packs around the road, the car parks and the shops. I had heard on many occasions their stated aim of shooting a policeman. The rumour was that this time the gangs were armed, with cheap hunting rifles and air pistols. But the only weapons I saw belonged to the police.

Later, on returning to my flat and watching the surprisingly dispassionate television coverage of what was going on in the banlieue, I reflected that Paris had become hardened to levels of violence that, in any other major European capital, would have threatened the survival of the government. The French were used to violence, to mini-riots and clashes between police and disaffected youth. Even in my own neighbourhood, the quiet district of Pernety, armed police regularly sealed off parts of the cité adjacent to the RER railway lines (the RER is the fast commuter train that connects the banlieues with the centre of Paris). Across the city, there were regular battles with police at the Gare du Nord, where an unnamed Algerian had recently been shot during another police bavure in the metro.

Outsiders

In the winter of 2007/8 I set out to learn more. I started by visiting the area around Bagneux, to the south of Paris. This is far from being the worst part of the banlieues: Courneuve and Sarcelles to the north are much more run-down and dangerous. These districts were portrayed in the 1995 film La Haine, in which a black, an Arab and a Jew, all from the banlieues, form an alliance against society. I found the film unconvincing, because I suspect that a Jew could never be friends with blacks and Arabs in this way. Also, although I know plenty of Jews in Paris, I don’t know a single Jew who lives in the banlieues, even though at one time the Jewish community flourished in the suburbs – there are still synagogues in Bagnolet and Montreuil which date from the 1930s.

Much more realistic, to my mind, were the intrigue and shocking violence of Michael Haneke’s film Caché (2005). This is a story of murderous revenge in which a middle-class French intellectual is disturbed by memories from a deeply repressed and violent past. His fears are related both to his mistreatment of an Algerian child adopted by his parents and to his complicity as a Frenchman in crimes committed by the French state against Algerians. Caché is set in the southern suburbs of Paris, not too far from Bagneux, the centre of which is much like any small French town. There is a church, a small market, cafés and green spaces. The architecture is not uniformly 1960s brutalism: there are cobbled streets and small, cottage-like houses.

The original meaning of banlieue dates back to the eleventh century, when the term bannileuga was used to denote an area beyond the legal jurisdiction of the city, where the poor lived. In the late fifteenth century, the poet and bandit François Villon described how Parisians feared and despised the coquillards, the army deserters and thieves who lived on the wrong side of the city wall. As Paris grew larger during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the original crumbling walls of the Old City, which marked the city limits, became known as les fortifs or la zone. This was marginal territory, with its own folklore and customs, a world of vagabonds, rag-pickers, drunks and whores. It was also the fertile ground that later produced street singers such as Fréhel and Edith Piaf, who dreamed and sang of le Grand Paris or Paname (slang for Paris), of the rich city centre only a few kilometres away from where they lived but which was as distant and alien as America.

In the 1920s and 1930s, as France began to industrialize rapidly, the population of the banlieues swelled with immigrants, mainly from Italy and Spain. The banlieues rouges (red suburbs), usually led by a Communist council, were key driving forces in the Front Populaire (the Popular Front), the working-class movement that swept to power in May 1936. This was the first truly left-wing government in France since the days of the Commune of 1871 (when a rag-bag of anarchists and workers’ groups held the city between March and May), and its success changed France for ever, with the introduction of paid holidays, a working week of forty hours and the sense that, for the first time, the workers were in control. During the trente glorieuses, the period of rapid economic growth that occurred between the 1950s and 1970s, other major towns across France adopted the Parisian model of building estates far outside the centre. The first developments of the new banlieues were sources of pride to the Parisian, Lyonnais and Marseillais working class, who were often grateful to be evacuated there from their slums in the city centre. Once, long ago, the banlieue was the future.

I remarked on this to Kevin, a rangy black lad of twenty who, with his mate Ludovic (roughly the same age), was showing photographer Nick Danziger and me around Bagneux. ‘I can’t imagine this as anyone’s future,’ Kevin said, gesturing at the car parks and boarded-up shops. ‘All anybody wants to do here is to escape.’

Both of them were obsessed with football, especially with the English Premier League. They were impressed that I had met and interviewed the French footballers Lilian Thuram, who is black, and Zinédine Zidane, who is from an Algerian family. Kevin himself was a footballer of average ability; he had a trial with Northampton Town in England. ‘I hate France sometimes,’ he told me. ‘And, at other times, I just stop thinking about it. But the real thing is that here, when you are born into an area and you are black or Arab, then you will never leave that area. Except maybe through football, and even that is shit in France.’

I asked him about his English name. ‘I like England. And, like everyone here, I don’t feel French, so why should I pretend?’ Ludovic, who has a more conventionally Gallic name but is originally from Mauritius, joined in: ‘They don’t like us in Paris, so we don’t have to pretend to be like them.’ By ‘them’ he means white French natives – Gaulois (Gauls) or fils de Clovis (Sons of Clovis – one of the first kings of France) in the language of the banlieue.

It is this Anglophilia, transmitted via the universal tongues of rap music and football, which explains why so many kids in the banlieues are called Steeve, Marky, Jenyfer, Britney or even Kevin. They don’t always get the spelling right, but the sentiment is straightforward: we are not like other French people; we refuse to be like them. As we walked and talked we soon entered a dark labyrinth of grey, crumbling concrete. This was ‘Darfour City’, a series of rectangular blocks of mostly boarded-up flats where the local drug dealers gathered. The police call it a quartier orange, largely a no-go area for the police themselves as well as for ordinary citizens.

DARFOUR CITY was scrawled across a door at the entrance to a block of flats. As we wandered deeper into the estate, there was more graffiti, in fractured English: FUCK DA POLICE; MIGHTY GHETTO. Halfway down the street we were hailed by a pack of lads, all black except for one white. They were all smoking spliffs. These were the local dealers, a gang of mates who, according to Kevin, could get you anything you wanted. They delighted in selling dope and coke at wildly inflated prices to wealthy Parisians. They were pleased to hear that I was English. ‘We hate the French press,’ said Charles, who is thin and tall and of Congolese origin. ‘They just think we’re animals.’ They then looked at me with suspicion. ‘No one comes here who isn’t afraid of us,’ said another, Majid. ‘That’s how it should be. That’s how we want it.’ The gang tired of me and my questions and I understood it was time to go.

Modern Warfare

In January 2006 a mobile-phone salesman named Ilan Halimi, aged twenty-three, was kidnapped in central Paris and driven out here to Darfour City. Halimi, who was Jewish, had been invited out for a drink by a young Iranian woman named Yalda, whom he had met while selling phones. It turned out that it was her mission to trap him and lure him away from safety. Yalda later described how Ilan had been seized by thugs in balaclavas and bundled into a car: ‘He screamed for two minutes with a high-pitched voice like a girl.’1

Three weeks later, Ilan was found naked and tied to a tree near the RER station of Sainte-Geneviève-des-Bois. He died on the way to hospital. His body had been mutilated and burned. Since being kidnapped, he had been imprisoned in a flat in Bagneux, starved and tortured. Residents of the block had heard his screams and the laughter of those torturing him, but had done nothing. Fifteen youths from the Bagneux district were arrested. They were members of a gang called the Barbarians, a loose coalition of hard cases, dealers and their girls, who shared a hatred of ‘rich Jews’. The alleged leader of the Barbarians, Youssef Fofana, went on the run to the Ivory Coast. He was later arrested and extradited and is now serving a life sentence in Clairvaux prison in the east of France. In the spring of 2012 he defied the French authorities by smuggling out from his cell videos in which he praises al-Qaeda and describes his capture as a ‘symbolic trophy for the Zionists of New York’. During his trial he described how he had dowsed Ilan in petrol and set fire to him with a cigarette lighter. He said he was ‘proud’ of what he had done.

Theories about the motives for the crime were initially confused. Was it a bungled kidnap? A Clockwork Orange-style act of pure sadism? Or was it the work of hate-fuelled anti-Semitism? The police were, at first, reluctant to admit this possibility. But Yalda, who turned out to be a member of the Barbarians, said in her testimony that the gang had specifically told her to entrap Jews. Her confession was widely reported, as was the fact that she called Fofana ‘Osama’, in homage to Bin Laden.

At the same time, out in the banlieues themselves, the murder took on a skewed new meaning: the word was that what had begun as a heist and kidnap to extort a ransom from ‘rich Jews’ had become a form of revenge for crimes in Iraq and, in particular, for events at Abu Ghraib prison. Bizarrely, in the view of some, this transformed the torturers i...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherFarrar, Straus and Giroux

- Publication date2014

- ISBN 10 0865479216

- ISBN 13 9780865479210

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages464

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The French Intifada: The Long War Between France and Its Arabs

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0865479216

The French Intifada: The Long War Between France and Its Arabs

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover0865479216

The French Intifada: The Long War Between France and Its Arabs

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0865479216

The French Intifada: The Long War Between France and Its Arabs

Book Description Condition: New. Book is in NEW condition. Seller Inventory # 0865479216-2-1

The French Intifada: The Long War Between France and Its Arabs

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0865479216

THE FRENCH INTIFADA: THE LONG WA

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.52. Seller Inventory # Q-0865479216