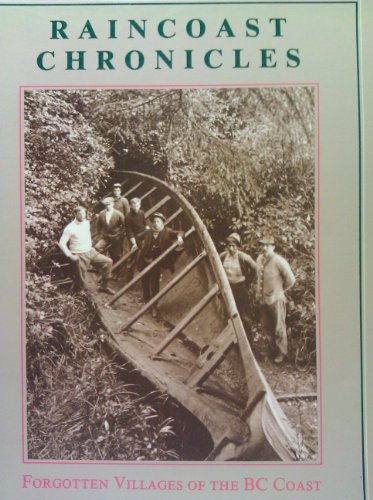

Items related to Raincoast Chronicles 11: Forgotten Villages of the...

A fascinating mix of prose, poetry, book reviews, artwork and photographs.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

AT EITHER END OF the Queen Charlotte Islands are the decaying remains of two of B.C.'s most successful whaling stations. Naden Harbour on Graham Island, and Rose Harbour on Kunghit Island processed hundreds of whales a season from 1910 to 1941. Canadian members of Captain Ahab's tribe set out from these stations in search of the elusive vapour blow that signalled a whale, and they harvested the herds of Blue, Finback, Sperm, and Humpback whales off the West Coast.

There were other whaling stations in B.C., all on Vancouver Island - Kyuquot, Sechart, and Page's Lagoon before World War II, and Coal Harbour after. Sechart was the first, and Kyuquot recorded the most whales caught, but the Queen Charlotte stations are known and remembered for their isolation, their thirty-odd years of service, and their violent storms.

Rose Harbour, situated on the south side of the rock-strewn Houston Stewart Channel, had access to the Pacific via Rose Inlet. This put it less than an hour's travel from the whaling grounds-an advantage over placid, sheltered Naden Harbour that cost dearly in adverse weather. The entire area is a sailor's nightmare, offering unexpected, conditional shelter to the knowing, and anxious, if not disastrous, moments to the ignorant. Captain Dode MacPherson, a whaler from 1916 to 1919, had vivid memories of Rose Harbour. "If the weather was good, we might lay off and let the boat drift during the night, but we seamen still stood our watch while everyone else could grab some shut-eye. Even the fireman could bank up his fires and bunk down for a few hours. The weather up there was atrocious, perhaps I should say abominable, unpredictable, and always adverse, and the currents contrary. But that's where the whales were, so that was where we went! We had a lot of fog up there, and when it wasn't foggy, the wind would be blowing. Often I swore it blew continually, and only paused to shift around and blow again from a different direction. The damnable thing about Rose was, there wasn't a decent place to anchor and get away from the weather, Even Sperm Bay didn't have good holding ground, unless you went right up to the head end and snuggled in behind the island.

"Those damn Willies would spring up in the middle of the night and shake you loose. Then we'd have to heave up the anchor, stow the chain, and steam around in the pitch blackness to find a place out of the wind in which to try again. Anthony Island, off the west coast, had good holding ground, but it was only a lee for a southerly wind; if she backed up to the west, we had to get the hell out of there, too. I didn't like Rose too much. We only went in there when we had whales, or needed grub or coal.

"The weather was better up at Naden, more steady, and we could spend more time whaling, and there were several good anchorages when we couldn't."

Charlie Watson had an eye for the rugged beauty of the Charlottes when he was an engineer on the whalers in the 1920s and 1950s. He talked at length about the natural sanctuary for the creatures of the wild, and the many artifacts of the aboriginal history of the area.

"We put in at Anthony Island in 1956, and I had a chance to go ashore and look around. I was sort of pointing out the sights to the other guys, but my god, I was shocked to find hardly anything left of the old graveyard. The only totem poles or lodge poles left were those rotting on the ground. There was nothing standing! Why, when I was there last with Willis Balcom, in 1923, there were dozens of totem poles, and more canoes than I cared to count. Know how they buried their chiefs? In a canoe, placed high up on posts so the animals can't get them, and their families were laid out in boxes around the base of the clan totem pole. God, they were big. All carved with the legendary symbols that told the family's story. They were very forboding to see, all leaning at various angles, glaring down at you as you entered the woods where they were hidden. The Indians wouldn't set foot on the island; they claimed it was haunted. But someone, probably tourists or fishermen, tore down all those totem poles and carted them away. How they did it, I can't guess. They were tremendous things. But there wasn't even a bleached bone left!

"Yes, it's all coming back to me as we talk. There was another' graveyard by an old Indian village down near the south end of Kunghit Island, but we never put in long enough to go ashore. But many of those old places have since been renamed in honour of the old whalers, like Balcom Inlet, Larsen Point, Orion Point, Germania Rock, and Grant Bank. Heater Harbour was named after Bill Heater, and Garcin Rocks after Alfus. There's a few more, but I can't put my finger on them right now.

"It's a great place, if you don't mind being a bit remote. You know, I believe it would be impossible for anyone to die of starvation in the Charlottes during the summer months. There were always deer close at hand at the head of those bays, and around Rose there was a special breed of elk that had been imported to the islands years before. They were very good eating, if you were lucky enough to shoot one," he chortled, recalling a happy incident of the past. "For anyone with the minimum of resources and ability, there was all kinds of berries, fish, fowl, and game available. But during the winter months it could be a pretty lonely and hungry place if you got into trouble. I believe the only hospital even now is at Charlotte City, and for a long time the only road there ran from the City up to Port Clements' beer parlour."

Charlie recounted a story involving Fisheye Thompson, another whaling engineer, to illustrate the plight of whalers drying out in such lonely outposts as Kyuquot, Rose, and Naden Harbours in the days before air travel and nearby beer parlours.

"Fisheye was a bit of an unstable chap at the best of times - a top-notch engineer, yes sir. Indeed he was. He was a man who could keep any bucket of bolts steaming right along, but he required a drink or two to do it and still keep his peace with the world. He had a notorious short fuse whenever his drinking supply ran out, and during one of those occasions, Buster Brown's fireman earned a crack across the head with a wheel spanner, that sent the poor man to hospital. Just because he had knocked a cock open on a tank full of lubricating oil, and it all drained down into the bilge!

"Hell, you know how it was around those places. If a man wanted a drink bad enough, there was always someone who would sell it to him, for a price. Why, even Bill Heater on the Grant found his standard compass drained of the alcohol, and water substituted. I'll bet someone paid a good price for that poison. Yes, there was always a little squeeze to be found around Rose Harbour when I worked out of there. I guess the term 'squeeze' came from the fact that anyone daring enough to risk his job to bring booze into the station could squeeze the last penny out of those dried-up drunks that needed it so badly! God knows, after a month or two of sobriety, those guys would have sold their own mothers for a drink. Of course it was almost worth your job to have it in your possession. The company was death on it. They'd had a lot of trouble from drinking during and after the war.

"Well, poor old Fisheye was desperate. His supply had run out, and no one at Rose had any they would sell him. So, when the Gray came in, Fisheye went after the strange little steward they had aboard her in those days, and managed to buy a few bottles of suspicious-looking stuff. God knows where that steward got it, but it must have been nearly poison. Well, Fisheye knocked back a couple of pints of that stuff and began acting like a raving lunatic. They had to ship him off to Essondale for quite a while to get over it. It was too bad. He was really a good engineer otherwise."

THE STATIONS HAD a distinctive appearance, and a smell even more distinctive. Built near the water on pilings driven down for footings, their timbers soon became saturated with oil from the whales they rendered down. Coal, their prime fuel, was piled high on the wharves to accommodate both the ships and the boiler house, which supplied steam power to run the station, and electricity to light it. The product of their endeavour was whale oil, and it was stored in large vertical tanks behind the stations, connected by pumps and pipes to the pierhead for delivery to the ships that transported it south to market. Gun powders and primers required by the whaling ships were stored in a powder shed, remote from work areas.

The station buildings were timbered and covered with corrugated iron; the sheds and houses were framed and clapboard-covered. Water was usually piped in from a convenient high-level stream or dam, and stored in large, wooden, water tanks which provided gravity feed to the houses and hose points. High-pressure service and fire points were supplied through steam-driven pumps. Outhouses were built on the outer end of piers that Jay offshore, and steam heat was laid on to some of the buildings, while coal-burning stoves and heaters sufficed for the rest. Little consideration was given to creature comfort, as the station operated only during the fair weather months from April to late October, but the company made sure that accommodations for the station crew and management were favourably situated for a fair wind and a garden patch to grow fresh vegetables.

Such concern for good, fresh food did not extend to the food the whalers ate. All meat and vegetables had to be shipped up from Victoria on the station tender. Vegetables often arrived dried and wizened, and Charlie Watson recalled, "Bad meat had to be the bane we all suffered without recourse. Oh, I remember once, a bunch of the boys showed the company just what they thought about it. My God, it was funny! Bill Rolls was manager at the time, and we and the Grant were tied up at the dock, taking on coal and supplies, when the Gray arrived with meat and supplies for the station. Well, you know how they carried the meat in those days - hung on hooks out on the open deck. Both the Gray and the Prince John had their boilers and engines aft, and, of course, that was where they hung the meat. The heat and soot ripened it till it was oozing slime and black with blowflies, hardly appetizing, even for people like us who had been waiting weeks for its delivery. The cooks from both ships had been given permission to take their meat at the pierhead, and got several of the deck crew to give them a hand. But once they saw the state it was in, they told the boys to heave it over the side into the chuck.

"This was the final insult to our crews. They had carried that rotten stinking mess from the slings over to the ship, the ooze dripping down over their clothes and hands. Then they were told to dump it over the side. Realizing the company was going it cheap rather than put in a proper meat locker on the Gray or have it shipped by a company with refrigeration, they decided it was time to show their displeasure. Keeping the rotten quarters of beef on their shoulders, they marched all the way up the dock to the station office and stalked inside, where they threw it right through the manager's plate glass door and left it lying on his carpet!"

Charlie roared with mirth as he recalled the incident, shaking his head slightly as he slapped a large paw down on his knee. "Oh, my god. There was a stink about that! If I recall rightly, they deducted the costs of repairing the door from the sailors' pay. But I'll say this for Rolls, he didn't fire anyone. After all, we all suffered when supplies were short.

"When we were desperate enough we'd even try whale meat! The Chinese usually cut some large pieces of meat off the Sei or small Finbacks, and left these hunks to hang till the outside turned black. More than once, when only salt beef or pork were our alternatives, we bartered with them for some of this. If you trimmed off the blackened meat and sliced the remainder into steaks or roasts, and cooked it over a slow fire, it was as good as some of that stringy beef, and tasted about the same. Of course, we always tried our hand at fishing or hunting when the opportunity presented itself, but if you're busy chasing whales there isn't much time left for anything else."

NADEN HARBOUR, BUILT in 1912, was typical of most stations built before World War 11. Each station had its slipway, a stoutly timbered and planked ramp that led up out of the water to the work decks and the buildings housing the rendering equipment, grinders, and driers required to convert the total whale into useful saleable products. Steam winches, fitted with heavy wire cables, dragged the whale up the wetted ramp, or whaleslip, till it reached the high water mark. The flensers climbed aboard the still-moving whale to begin slicing the blubber into strips with their long, wooden-handled, curved, flensing knives. These strips started at the head area and extended the full length to the tail, where the wire cable had been attached to haul the whale ashore. At the head end of the strip, a hole for the hook line was cut in. The strip of blubber was slightly undercut at the head end to allow it to fold back over itself. When it was pulled by the hook line from the stripping winch, it peeled back for the whole length of the whale with a sharp cracking sound that was not unlike that of an under-ripe banana being peeled.

Each strip was hauled up to the cutting deck and hacked into small chunks, then fed into the rendering kettles. The carcass was pulled up to the meat floor, where it was butchered into reasonably small chunks and placed in pressure cookers to render off the oil. Steam-powered saws cut up the bone. If the catch was a Sperm whale, the spermaceti was baled out of the head box, and the digestive tract was examined for ambergris.

After the cookers and kettles had rendered off most of the available oils, the bones were separated from the meat and stored on a bone pile, ready for grinding into bone meal during a lay day, or at the end of the season. The meat was ground, then dried in either flame-type or steamjacketed rotary kiln dryers. In some stations, this dried meal was ground again to bring it down to the consistency of a powder, and was mixed with either the whale blood, which had also been dried and ground to a powder, or with the bone meal, to supply the various needs of the whale product market.

Although all were similar, each station had its own unique characteristics. Win Garcin spent many school summer holidays at Rose when his father was station manager, and he remembers, "Rose Harbour was mostly built on muskeg. There were deep pilings sunk to support the station and the boardwalk. If you got off those boardwalks, you'd sink up to your knees in muskeg and water. You couldn't wander too far away at Rose!

"There were flowers everywhere. Forget-me-nots, bluebells, snowdrops, and many others whose names I don't know. There were wild berries, huckleberries, blueberries, and wild strawberries. Underfoot was moss, lush moss, ankle deep and alive with shrews, moles, and all kinds of insects. The bushes and flowers were alive with bees, and the trees alive with birds. The place sang with nature's music. So warm and secure. The huge trees stood solid and tall against the sky, and the eagles... Hundreds and hundreds of them, wheeling and diving, swooping and gliding silently away up in the sky. I used to get the watchman's boat and row around, looking at all the various small islands and rocks. There were seals, sea lions, gooney birds, and sea parrots. You know the one...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherHarbour Publishing

- Publication date1987

- ISBN 10 0920080405

- ISBN 13 9780920080405

- BindingPaperback

- Edition number1

- Number of pages76

- EditorWhite Howard

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 4.00

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Raincoast Chronicles 11: Forgotten Villages of the BC Coast

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_0920080405

Raincoast Chronicles 11: Forgotten Villages of the BC Coast

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think0920080405

Raincoast Chronicles 11: Forgotten Villages of the BC Coast

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard0920080405

RAINCOAST CHRONICLES 11: FORGOTT

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 0.5. Seller Inventory # Q-0920080405