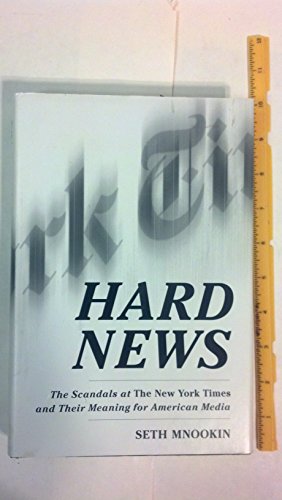

Items related to Hard News: The Scandals at The New York Times and Their...

On May 11, 2003, The New York Times devoted four pages of its Sunday paper to the deceptions of Jayson Blair, a mediocre former Times reporter who had made up stories, faked datelines, and plagiarized on a massive scale. The fallout from the Blair scandal rocked the Times to its core and revealed fault lines in a fractious newsroom that was already close to open revolt.

Staffers were furious–about the perception that management had given Blair more leeway because he was black, about the special treatment of favored correspondents, and most of all about the shoddy reporting that was infecting the most revered newspaper in the world. Within a month, Howell Raines, the imperious executive editor who had taken office less than a week before the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001–and helped lead the paper to a record six Pulitzer Prizes for its coverage of the attacks–had been forced out of his job.

Having gained unprecedented access to the reporters who conducted the Times’s internal investigation, top newsroom executives, and dozens of Times editors, former Newsweek senior writer Seth Mnookin lets us read all about it–the story behind the biggest journalistic scam of our era and the profound implications of the scandal for the rapidly changing world of American journalism.

It’s a true tale that reads like Greek drama, with the most revered of American institutions attempting to overcome the crippling effects of a leader’s blinding narcissism and a low-level reporter’s sociopathic deceptions. Hard News will shape how we understand and judge the media for years to come.

Staffers were furious–about the perception that management had given Blair more leeway because he was black, about the special treatment of favored correspondents, and most of all about the shoddy reporting that was infecting the most revered newspaper in the world. Within a month, Howell Raines, the imperious executive editor who had taken office less than a week before the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001–and helped lead the paper to a record six Pulitzer Prizes for its coverage of the attacks–had been forced out of his job.

Having gained unprecedented access to the reporters who conducted the Times’s internal investigation, top newsroom executives, and dozens of Times editors, former Newsweek senior writer Seth Mnookin lets us read all about it–the story behind the biggest journalistic scam of our era and the profound implications of the scandal for the rapidly changing world of American journalism.

It’s a true tale that reads like Greek drama, with the most revered of American institutions attempting to overcome the crippling effects of a leader’s blinding narcissism and a low-level reporter’s sociopathic deceptions. Hard News will shape how we understand and judge the media for years to come.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Seth Mnookin is a former media columnist for Newsweek, where he also covered politics, crime, and popular culture. His writing has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times Book Review, Slate, Spin, and elsewhere. A 2004 Joan Shorenstein Fellow at Harvard’s Kennedy School, he lives in New York City.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

April 8, 2002

The third-floor newsroom of The New York Times, located about one hundred yards west of Times Square, can be a grim place. The exposed ventilation system, the humming fluorescent lights, the claustrophobic cubicles, and the standard-issue off-white paint job make the newsroom feel simultaneously retro and futuristic, as if the Times’s nerve center were designed as a contemporary interpretation of the stereotypical city room of old. For many of the hundred-plus metro, national, and business reporters whose desks are on the third floor, the newsroom is an intensely stressful place to work, a place where career-long reputations can be badly dented by one deadline-induced mistake, a place where staffers fight ruthlessly over bylines and credit. One metro reporter described the newsroom as a simulacrum of a bitterly competitive premed program, where success is strictly relative and no one can achieve without someone else failing. Reporters, especially those lower on the slippery newsroom totem pole, carry with them a jangling fear of looking dumb in front of their editors, of falling out of favor, of failing to deliver. Max Frankel, the retired executive editor of the Times, once quipped that he enjoyed the paper only when he was away from the office, reading it.

The newsroom’s uninspiring décor and its vaguely Hobbesian feel contrasts mightily with, say, the minimalist sophistication and noblesse- oblige ethos that pervade the Condé Nast building, located a block from the Times’s headquarters. Condé Nast, home to high-end magazines like The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, Vogue, and GQ, has a Frank Gehry—designed cafeteria and special guest chefs from Hong Kong and Tuscany. The Times has a commissary furnished with plastic ferns and Formica tables. Condé Nast writers get generous expense accounts, flexible deadlines, and private offices with frosted-glass doors and wood-paneled bookshelves. Times reporters get embittered copy editors and off-beige desk dividers. What’s more, Times reporters and editors are, on average, paid less and work more than their colleagues in the glossy magazine world.

But Timesmen, of course, get an immeasurable level of prestige and an inexorable sense of purpose. They get the recurring adrenaline rush of knowing that they have the power to move markets, to influence elections, to shape world affairs. They get their fingerprints (and their bylines) on the first rough drafts of history. In this regard, at least, not much has changed since the 1960s. In his fascinating 1969 bestseller, The Kingdom and the Power, author and former Times reporter Gay Talese described how the political and cultural elite looked to the paper he worked at for more than a decade as “necessary proof of the world’s existence, a barometer of its pressure, an assessor of its sanity.”

On most days, this power is barely acknowledged. Reporters push their way in through the Times’s revolving doors on the north side of West Forty-third Street around ten in the morning. Soon after, section editors begin working the floor, checking for scoops or updates or new angles on old stories. By noon, reporters write up “sked lines,” one- or two-sentence summaries that their editors can use at the daily page-one meeting to pitch their stories. A couple of hours later, if a reporter has picked up a breaking news story, as opposed to a feature or an off-news color piece, there’s the familiar ritual of canceled dinner plans, apologetic phone calls to frustrated spouses, thrice-postponed drinks dates postponed one more time. By 8:00 or 9:00 p.m., after circling back to this or that source for a juicier quote or a flashier anecdote, when it’s finally time to stumble out into Times Square’s neon-lit frenzy, there’s still an hour or two of cellphone queries from copy editors to look forward to. Isn’t there anyone who’d go on the record about the mayor’s new parking initiative? Would you mind if we changed your lead around?

Such a schedule leaves very little time for self-congratulation, but the afternoon of April 8, 2002, was a break from the numbing daily slog, a time to pause and celebrate The New York Times’s unique role in American society. The seven months since the September 11 terrorist attacks had been defined by balls-out reporting, seven months in which countless staffers worked without a single day off, seven months in which reporters were relocated from local government beats to war zones throughout the Middle East and in Afghanistan.

As the day stretched toward 3:00 p.m., a space was cleared in front of the spiral staircase that connects the third and fourth floors of the Times’s newsroom. The New York Times was about to win seven Pulitzer Prizes, half of all the Pulitzers awarded for journalism and four more than the previous one-year record the Times shared with two other newspapers.* Six of the awards that year recognized the paper’s coverage of the September 11 attacks on America. It was as if the Pulitzer board were affirming the Times’s place as the center of the journalistic universe.

*In 2004, the Los Angeles Times won five Pulitzer Prizes.

After Sig Gissler, the administrator of the Pulitzer Prizes, made the official announcement from Columbia University, Raines, a short, bow-legged Alabamian with brushy gray hair and a bulbous nose, strode up to a small wooden platform underneath the staircase. Reporters and editors snaked up the stairs and jammed the hallways. For the first time in The New York Times’s storied and celebrated history, all of the paper’s living executive editors had gathered in one room. A.M. Rosenthal, who hadn't been inside the Times's West Forty-Third Street building since his rambling Op-Ed page column had been canceled two and a half years earlier, was there. Rosenthal’s successor, Max Frankel, one of the few men who inspired fear in Raines (and who was said to have resigned early to block the possibility of Raines’s ascension in the early 1990s), was there. Joe Lelyveld, Raines’s immediate predecessor, was there, along with the man Lelyveld had openly campaigned for as his successor, former managing editor Bill Keller, now a biweekly Op-Ed page columnist and Times Magazine writer. Assembling these five men in one room was a major undertaking of its own. Rosenthal’s and Frankel’s mutual disdain was legendary. Frankel had been particularly insulting to Rosenthal in his memoir, in which he referred to himself approvingly as “the not-Abe.” And Lelyveld, who since leaving the Times had been working on lengthy pieces for The New Yorker and The New York Review of Books, made no secret of how happy he was to have moved on to the next phase of his life.

Off to the side of the wooden platform, a stooped and frail old man overshadowed even this summit of journalistic lions. Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, known both inside and outside the paper simply as “Punch,” was making one of his increasingly rare trips to the newsroom. Punch had handed over the publisher’s title to his son in 1992 and had given Arthur Ochs Sulzberger Jr.–or “Young Arthur,” as he was sometimes known–the title of chairman of the New York Times Company in 1997. (Behind his back, Sulzberger Jr. was occasionally referred to as “Pinch,” a moniker he found demeaning. “A man deserves his own nickname,” he once said.) Punch leaned in to speak quietly with Lelyveld, two legends of American journalism watching a new generation eclipse their accomplishments.

To a round of applause, Raines stepped onto the platform. “I was reminded today of the words of Mississippi’s greatest moral philosopher, Dizzy Dean,” Raines, a proud southerner leading the most elite of northern institutions, told the throng of journalists. “ ‘It ain’t bragging if you really done it.’ Ladies and gentlemen of The New York Times, you’ve really done it.” On that day, Raines was eloquent and forceful, humble and proud. “We are ever mindful of the shattering events it was our task to record in our city, nation, and world community,” he said. It was also important to realize, he added, that the Times’s Septem- ber 11 journalism “will be studied and taught as long as journalism is studied and practiced. . . . We have a right to celebrate these days of legend at The New York Times.” Raines made a point of acknowledging and thanking Lelyveld and Keller–it was, after all, the staff they had assembled and trained that won all those Pulitzers–before handing over the microphone to Arthur Sulzberger Jr., whom he called “a great publisher.”

Punch, a shy and private man, was probably just as happy that Raines hadn’t singled him out. Raines later told Ken Auletta, the New Yorker media writer whom he had invited into the newsroom to record the scene, that he intentionally didn’t mention the elder Sulzberger so that his son would have a chance to pay homage to the family patriarch. But to some in the newsroom, it was a noticeable and telling slight, a sign that Raines’s humility and graciousness were nothing but lip service. “Howell mentioned a lot of folks on whose shoulders we stand, but he forgot one,” Arthur Sulzberger told the crowd. “And I’m grateful that he did, and that is my father.” THE SULZBERGER FAMILY Every company likes to refer to itself–at least publicly–as a family. Most of the time, that’s a specious metaphor. But in the case of The New York Times, the analogy is nearly accurate. It’s true that The New York Times existed before Adolph Ochs came on the scene–it was founded in 1851 as a daily broadsheet. But the modern incarnation of the Times was born in 1896, when a virtually bankrupt thirty-eight-year-old first-generation American named Adolph Ochs ...

The third-floor newsroom of The New York Times, located about one hundred yards west of Times Square, can be a grim place. The exposed ventilation system, the humming fluorescent lights, the claustrophobic cubicles, and the standard-issue off-white paint job make the newsroom feel simultaneously retro and futuristic, as if the Times’s nerve center were designed as a contemporary interpretation of the stereotypical city room of old. For many of the hundred-plus metro, national, and business reporters whose desks are on the third floor, the newsroom is an intensely stressful place to work, a place where career-long reputations can be badly dented by one deadline-induced mistake, a place where staffers fight ruthlessly over bylines and credit. One metro reporter described the newsroom as a simulacrum of a bitterly competitive premed program, where success is strictly relative and no one can achieve without someone else failing. Reporters, especially those lower on the slippery newsroom totem pole, carry with them a jangling fear of looking dumb in front of their editors, of falling out of favor, of failing to deliver. Max Frankel, the retired executive editor of the Times, once quipped that he enjoyed the paper only when he was away from the office, reading it.

The newsroom’s uninspiring décor and its vaguely Hobbesian feel contrasts mightily with, say, the minimalist sophistication and noblesse- oblige ethos that pervade the Condé Nast building, located a block from the Times’s headquarters. Condé Nast, home to high-end magazines like The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, Vogue, and GQ, has a Frank Gehry—designed cafeteria and special guest chefs from Hong Kong and Tuscany. The Times has a commissary furnished with plastic ferns and Formica tables. Condé Nast writers get generous expense accounts, flexible deadlines, and private offices with frosted-glass doors and wood-paneled bookshelves. Times reporters get embittered copy editors and off-beige desk dividers. What’s more, Times reporters and editors are, on average, paid less and work more than their colleagues in the glossy magazine world.

But Timesmen, of course, get an immeasurable level of prestige and an inexorable sense of purpose. They get the recurring adrenaline rush of knowing that they have the power to move markets, to influence elections, to shape world affairs. They get their fingerprints (and their bylines) on the first rough drafts of history. In this regard, at least, not much has changed since the 1960s. In his fascinating 1969 bestseller, The Kingdom and the Power, author and former Times reporter Gay Talese described how the political and cultural elite looked to the paper he worked at for more than a decade as “necessary proof of the world’s existence, a barometer of its pressure, an assessor of its sanity.”

On most days, this power is barely acknowledged. Reporters push their way in through the Times’s revolving doors on the north side of West Forty-third Street around ten in the morning. Soon after, section editors begin working the floor, checking for scoops or updates or new angles on old stories. By noon, reporters write up “sked lines,” one- or two-sentence summaries that their editors can use at the daily page-one meeting to pitch their stories. A couple of hours later, if a reporter has picked up a breaking news story, as opposed to a feature or an off-news color piece, there’s the familiar ritual of canceled dinner plans, apologetic phone calls to frustrated spouses, thrice-postponed drinks dates postponed one more time. By 8:00 or 9:00 p.m., after circling back to this or that source for a juicier quote or a flashier anecdote, when it’s finally time to stumble out into Times Square’s neon-lit frenzy, there’s still an hour or two of cellphone queries from copy editors to look forward to. Isn’t there anyone who’d go on the record about the mayor’s new parking initiative? Would you mind if we changed your lead around?

Such a schedule leaves very little time for self-congratulation, but the afternoon of April 8, 2002, was a break from the numbing daily slog, a time to pause and celebrate The New York Times’s unique role in American society. The seven months since the September 11 terrorist attacks had been defined by balls-out reporting, seven months in which countless staffers worked without a single day off, seven months in which reporters were relocated from local government beats to war zones throughout the Middle East and in Afghanistan.

As the day stretched toward 3:00 p.m., a space was cleared in front of the spiral staircase that connects the third and fourth floors of the Times’s newsroom. The New York Times was about to win seven Pulitzer Prizes, half of all the Pulitzers awarded for journalism and four more than the previous one-year record the Times shared with two other newspapers.* Six of the awards that year recognized the paper’s coverage of the September 11 attacks on America. It was as if the Pulitzer board were affirming the Times’s place as the center of the journalistic universe.

*In 2004, the Los Angeles Times won five Pulitzer Prizes.

After Sig Gissler, the administrator of the Pulitzer Prizes, made the official announcement from Columbia University, Raines, a short, bow-legged Alabamian with brushy gray hair and a bulbous nose, strode up to a small wooden platform underneath the staircase. Reporters and editors snaked up the stairs and jammed the hallways. For the first time in The New York Times’s storied and celebrated history, all of the paper’s living executive editors had gathered in one room. A.M. Rosenthal, who hadn't been inside the Times's West Forty-Third Street building since his rambling Op-Ed page column had been canceled two and a half years earlier, was there. Rosenthal’s successor, Max Frankel, one of the few men who inspired fear in Raines (and who was said to have resigned early to block the possibility of Raines’s ascension in the early 1990s), was there. Joe Lelyveld, Raines’s immediate predecessor, was there, along with the man Lelyveld had openly campaigned for as his successor, former managing editor Bill Keller, now a biweekly Op-Ed page columnist and Times Magazine writer. Assembling these five men in one room was a major undertaking of its own. Rosenthal’s and Frankel’s mutual disdain was legendary. Frankel had been particularly insulting to Rosenthal in his memoir, in which he referred to himself approvingly as “the not-Abe.” And Lelyveld, who since leaving the Times had been working on lengthy pieces for The New Yorker and The New York Review of Books, made no secret of how happy he was to have moved on to the next phase of his life.

Off to the side of the wooden platform, a stooped and frail old man overshadowed even this summit of journalistic lions. Arthur Ochs Sulzberger, known both inside and outside the paper simply as “Punch,” was making one of his increasingly rare trips to the newsroom. Punch had handed over the publisher’s title to his son in 1992 and had given Arthur Ochs Sulzberger Jr.–or “Young Arthur,” as he was sometimes known–the title of chairman of the New York Times Company in 1997. (Behind his back, Sulzberger Jr. was occasionally referred to as “Pinch,” a moniker he found demeaning. “A man deserves his own nickname,” he once said.) Punch leaned in to speak quietly with Lelyveld, two legends of American journalism watching a new generation eclipse their accomplishments.

To a round of applause, Raines stepped onto the platform. “I was reminded today of the words of Mississippi’s greatest moral philosopher, Dizzy Dean,” Raines, a proud southerner leading the most elite of northern institutions, told the throng of journalists. “ ‘It ain’t bragging if you really done it.’ Ladies and gentlemen of The New York Times, you’ve really done it.” On that day, Raines was eloquent and forceful, humble and proud. “We are ever mindful of the shattering events it was our task to record in our city, nation, and world community,” he said. It was also important to realize, he added, that the Times’s Septem- ber 11 journalism “will be studied and taught as long as journalism is studied and practiced. . . . We have a right to celebrate these days of legend at The New York Times.” Raines made a point of acknowledging and thanking Lelyveld and Keller–it was, after all, the staff they had assembled and trained that won all those Pulitzers–before handing over the microphone to Arthur Sulzberger Jr., whom he called “a great publisher.”

Punch, a shy and private man, was probably just as happy that Raines hadn’t singled him out. Raines later told Ken Auletta, the New Yorker media writer whom he had invited into the newsroom to record the scene, that he intentionally didn’t mention the elder Sulzberger so that his son would have a chance to pay homage to the family patriarch. But to some in the newsroom, it was a noticeable and telling slight, a sign that Raines’s humility and graciousness were nothing but lip service. “Howell mentioned a lot of folks on whose shoulders we stand, but he forgot one,” Arthur Sulzberger told the crowd. “And I’m grateful that he did, and that is my father.” THE SULZBERGER FAMILY Every company likes to refer to itself–at least publicly–as a family. Most of the time, that’s a specious metaphor. But in the case of The New York Times, the analogy is nearly accurate. It’s true that The New York Times existed before Adolph Ochs came on the scene–it was founded in 1851 as a daily broadsheet. But the modern incarnation of the Times was born in 1896, when a virtually bankrupt thirty-eight-year-old first-generation American named Adolph Ochs ...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherRandom House

- Publication date2004

- ISBN 10 1400062446

- ISBN 13 9781400062447

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages352

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 28.04

Shipping:

US$ 4.25

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Hard News: The Scandals at The New York Times and Their Meaning for American Media

Published by

Random House

(2004)

ISBN 10: 1400062446

ISBN 13: 9781400062447

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1400062446

Buy New

US$ 28.04

Convert currency

Hard News: The Scandals at The New York Times and Their Meaning for American Media Mnookin, Seth

Published by

Random House

(2004)

ISBN 10: 1400062446

ISBN 13: 9781400062447

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # NHK--276

Buy New

US$ 29.00

Convert currency

Hard News: The Scandals at The New York Times and Their Meaning for American Media Mnookin, Seth

Published by

Random House

(2004)

ISBN 10: 1400062446

ISBN 13: 9781400062447

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # RCBP--0292

Buy New

US$ 34.00

Convert currency

HARD NEWS: THE SCANDALS AT THE N

Published by

Random House

(2004)

ISBN 10: 1400062446

ISBN 13: 9781400062447

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: New. New. In shrink wrap. Looks like an interesting title! 1.32. Seller Inventory # Q-1400062446

Buy New

US$ 57.60

Convert currency