Items related to Going Home to Glory: A Memoir of Life with Dwight D....

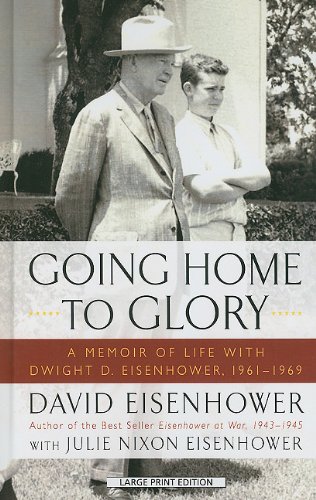

Going Home to Glory: A Memoir of Life with Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1961-1969 (Thorndike Press Large Print Biography) - Hardcover

An intimate portrait of the 34th president by his grandson draws on personal stories and writings to chronicle his final years during the author's coming-of-age period, describing various aspects of Eisenhower's character and his contributions to successive presidential administrations. (biography & autobiography).

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

GETTYSBURG

GOING HOME

In the late afternoon of Inauguration Day, January 20, 1961, Dwight and Mamie Eisenhower drove north to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in the 1955 Chrysler Imperial that Mamie had purchased for Ike on his sixty-fifth birthday. The outgoing President and First Lady, their personal servants, Sergeant John Moaney and Rosie Woods, and chauffeur, Leonard Dry, sat together in the roomy car. There was an eerie loneliness about the absence of motorcycle escorts and caravans of Secret Service and press cars. A single Secret Service vehicle with driver and agent led the Chrysler. When the Eisenhowers approached the entrance to their Gettysburg farm, the Secret Service honked the horn and made a U-turn, heading back to Washington.

The Eisenhowers’ itinerary had been published in newspapers. Despite a blizzard the night before and below-freezing temperatures, friendly groups in twos and threes lined the road between Washington and Frederick, Maryland. Near Emmitsburg, on Route 15, the crowds grew larger. The nuns, priests, and students of Mount St. Mary’s and St. Joseph’s colleges, bundled in overcoats and scarves, congregated along the road bearing “Welcome Home” signs.

In Gettysburg, a festive mood reigned. Over sixty civic organizations prepared for celebrations scheduled the following evening in the town square welcoming the Eisenhowers home as private citizens. Henry Scharf, owner of the Gettysburg Hotel and host of the “Welcome Home Day” celebration, was pleased that Eisenhower had selected Gettysburg to retire. The Eisenhowers would not only mean tourism, but also add to the historical stature of the community. Scharf, like the majority of the townspeople, had a sense of history about Gettysburg. His study at home was packed with books on the Civil War, World War II, and the American Revolution. By the untidy appearance of his study, one judged he used those references constantly, and he did. He was convinced Eisenhower’s decision to retire to Gettysburg was an affirmation of the town’s historical uniqueness.

As Scharf said to his wife, Peggy, “This is the greatest thing to happen to this town since the battle. This man is beloved by everyone, including his opponents. He is the best-loved president since Lincoln.”

But there was a difference. While in office, Lincoln had been one of the most maligned presidents in American history. His stature had grown with the passage of time and he was linked to Gettysburg by his unforgettable address at the dedication of the National Cemetery. Eisenhower, on the other hand, was perhaps the most popular president while in office, but his reputation might not grow like Lincoln’s, might in fact diminish.

Earlier that morning, Scharf’s daughter, Elise, scurried about her Alexandria, Virginia, apartment collecting a few necessities for the journey to Gettysburg along the precise route the Eisenhower party would take. Not only was Elise needed at home to assist with the multicourse dinner arrangements; she also eagerly anticipated a chance to see the Eisenhowers close-up and perhaps even to chat. Elise admired President Eisenhower and had seen him from a distance on the few occasions her father’s staff had been involved in catering functions on the grounds of the Gettysburg farm. She had gone along as a member of the kitchen or grounds crew, just for a glimpse. Now, as far as she and several thousand other Gettysburgians were concerned, the Eisenhowers were becoming neighbors. Nobody planned to bother them or to ask them to appear at social gatherings and club functions. Everyone expected that eventually the Eisenhowers would take some active part in the community, but no one would impose.

The weather was ominous. Elise worried that she would be blocked by the accumulating snowdrifts, which were paralyzing the capital city and the roads leading to southern Pennsylvania. Snow had fallen heavily the night before, and the entire Potomac Basin was frozen. Temperatures had plummeted. As the ceremonies inaugurating John Kennedy as the thirty-fifth president drew to a conclusion, Elise called the Maryland State Police to learn the status of the northbound roads. She found out that nothing could be guaranteed after three o’clock but that if she left immediately, she had a reasonable chance of getting home.

Additionally, she reasoned, if she could reach Route 15 at Frederick, the remainder of the road running through Thurmont and Emmitsburg would be kept open for the Eisenhower motorcade. Elise set off on her uncertain trek and eventually joined up five minutes behind the bittersweet Eisenhower procession.

Every mile, Elise saw evidence that the Eisenhower motorcade had passed through minutes before. She saw discarded signs reading “Welcome Home,” and the dispersing throngs who moments earlier had braved the cold to ease Eisenhower’s transition to private life. In Emmitsburg, Peggy passed the congregation of nuns packing up blankets and signs outside of St. Joseph’s College. Upon arriving in Gettysburg, she learned of improving forecasts for the 21st, calling for frigid weather but gradually diminishing snowfall. The ceremonies set for the next day were on.

———

At dinnertime, my grandparents drove directly to our home, a former schoolhouse that stood on the corner of their farm. My three younger sisters, Anne, eleven, Susan, nine, Mary Jean, five, and I, now a grown-up twelve years old, had watched the inauguration at home in Gettysburg. I remembered thinking that it should have been the Nixons moving into the White House—and then thinking that being twelve and fourteen years old, the ages of Julie and Tricia Nixon, would be a terrible time to have Secret Service agents. I would miss the men on my detail, but not their constant guarding of Gran One, Gran Two, Gran Three, and Gran Four, the official Secret Service names for my sisters and me.

Everyone now seemed animated and happy, in sharp contrast to the air of numbing tension in the White House several weeks earlier. Relaxed, Granddad listened intently to every word spoken and seemed to say less than usual. He basked in the attention, joking lightly. Characteristically, he wandered frequently into the kitchen to supervise dinner preparations by Sergeant Moaney and his wife, Delores, who had arrived at the farm earlier in the day. Moaney had joined Granddad’s staff as his orderly in the early months of the war in Europe and Delores had become my grandparents’ cook after the war.

My father, John, broke the spell of gaiety toward the end of the evening, standing up from the dinner table to speak. He reviewed briefly Granddad’s accomplishments and then spoke of the years before the fame. As a small, tight-knit family of three, the Eisenhowers had seen much of the world. They had lived in Paris and in Washington both before and during the Depression. They then went on to the Philippines and four years of service under General Douglas MacArthur. The war had dispersed the family, John going to West Point, Mamie returning to Washington, and Dwight Eisenhower going on, in Douglas MacArthur’s words, to “write his name in history.” Dad recalled that the decision to run for president had been difficult, but in the end, Dwight Eisenhower had returned from his NATO command to lead the country through eight years of peace and prosperity. Dad spoke of the experience of a lifetime he had had serving his father in the West Wing.

“Leaving the White House will not be easy at first,” Dad said. “But we are reunited as a family, and this”—Dad gestured to all of us seated, and outside toward the farm—“is what we have wanted. I suppose that tonight, we welcome back a member of this clan who has done us proud.” Dad raised his glass in a toast.

Too moved to reply, Granddad simply held his glass high and joined in the “hear, hear.”

———

It had been a long day. Earlier, Eisenhower had transferred power to John F. Kennedy. That morning, after coffee at the White House and a brief pause at the North Portico for the benefit of newsmen, photographers, and television cameras, Eisenhower and Kennedy had driven off to the Capitol wearing top hats in place of the homburgs that Eisenhower had sought to install as a tradition at his inaugural in 1953. The tradition, Time noted, “will end with his [Eisenhower’s] administration.”

Slowly the black limousine bearing the oldest and second-youngest presidents in U.S. history had rolled toward the gleaming Capitol building, past the crowd estimated at nearly a million people lining Washington’s broad boulevards and gradually filling the newly installed tiers of spectator’s stands. In December, Eisenhower had ruefully likened the stands appearing around the White House and along the inaugural parade route to “scaffolds.” By that comment Eisenhower might have been mindful of his inauguration eight years earlier. After he and Harry Truman exchanged only a few words during the entire ceremony, Truman’s departure, in Eisenhower’s mind, had taken on the character of a hanging. But in January 1961, Harry Truman, busy making the rounds of inaugural parties, appeared to have forgotten the affair. On the 19th, Truman told reporters he had “no advice” regarding Eisenhower’s retirement, adding that as far as he was concerned, Eisenhower was “a very nice person.”

Eisenhower was being handled gently, even affectionately, as he went through the ritual of laying down power. Since November, Kennedy had been at his cordial best. Before the inaugural ceremony, Eisenhower and Kennedy had chatted amicably in the Red Room. For his part, Kennedy was almost alight with the intense media excitement over his ascension to power.

Eisenhower had been busy in January preparing his final messages to the American people. In his eighth State of the Union address, he declared the state of the union to be sound. He reminded the country that for eight years Americans had “lived in peace.” Eisenhower listed his administration’s measures that had ensured the peace: the ballistic missile program, strong support for foreign aid, a series of alliances ringing the Sino-Soviet landmass, and efforts to open talks between East and West. Two weeks later, in his farewell address to the nation, Eisenhower had expressed forebodings about the domestic implications of a permanent state of mobilization without war, warning that a “military industrial complex” could undermine democratic self-rule.

But Eisenhower’s message fell on deaf ears. The inaugural coincided with a period of turmoil. Nikita Khrushchev in early January issued an ominous declaration. Aimed partly at China, partly at the United States, he endorsed “wars of national liberation,” a program of Soviet support for insurgencies and sabotage worldwide against the remnants of Western colonialism. In Laos, North Vietnamese battalions operated with Pathet Lao units in a battle against pro-Western forces for control of the strategic Plain of Jars. In Cuba, Fidel Castro paraded Soviet-built tanks and Cuban militiamen through downtown Havana, proclaiming his preparedness against a rumored invasion from the north. In France, voters approved a referendum endorsing Charles de Gaulle’s program to end the war in Algeria, setting the stage for France’s capitulation to the rebel forces. Throughout Belgium, half a million workers, teachers, and businessmen protested the government’s austerity program, enacted because of the wrenching loss of the Congo and the end of colonialism in Africa.

Kennedy disagreed with Eisenhower’s optimism about the state of the union and now it was his turn to speak. In January, the president-elect had proclaimed before the Massachusetts legislature that his government would “always consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill—the eyes of all the people are upon us.” Now center stage, on the threshold of assuming the presidency, Kennedy wanted to convey a sense of urgency, to “rekindle the spirit of the American revolution,” and to ask for greater exertions by the American people. In New York on September 14, he had declared his presidency would be “a hazardous experience,” predicting, “We will live on the edge of danger.”

Minor mishaps enriched the pageantry of the Kennedy inaugural. Cardinal Cushing’s invocation was interrupted by a short circuit in the electric motor powering the heating system that warmed the seated dignitaries. Mamie Eisenhower first noticed the smoke and for several awkward moments the assembled officials on the platform scurried about in confusion. The winter sun’s glare temporarily blinded poet Robert Frost at the lectern, and forced him to recite from memory a poem he had published in 1942 titled “The Gift Outright,” rather than the poem he had written for the inaugural.

Following the administration of the oath, Kennedy delivered the most memorable inaugural speech since Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s in 1933. The young president achieved eloquence, an inspirational quality, a tone of defiance and resolve. He repudiated the confident premise of the Eisenhower administration. “Only a few generations,” he declared, “have been granted the role of defending freedom in its hour of maximum danger. I welcome this responsibility.”

Kennedy drew attention to his youth and to his awareness that this was a moment of transition from wartime to postwar leadership.

We dare not forget today that we are the heirs of that first revolution. Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch is passed to a new generation of Americans—born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage—and unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this nation has always been committed, and to which we are committed today, at home and around the world.

To Khrushchev’s promise to subsidize “wars of national liberation,” Kennedy replied:

Let every nation know whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend or oppose any foe to assure the survival and success of liberty. This much we pledge and more.

Implying years of inaction under Eisenhower, he cried: “But let us begin . . . let us begin anew.”

The Los Angeles Times noted about Kennedy: “He is wrong in implying the beginning came with him, but he is right in suggesting that the perfecting of mankind is tedious and unpredictable.” But Time magazine had applauded Kennedy’s “lean, lucid phrases,” noting his message had “profound meaning for the US future.”

Fourteen years later, author Robert Nisbet, criticizing the liberals’ fondness for crisis, wrote that “crisis is always an opportunity for a break with the despised present, liberation from the kinds of authority which are most repugnant to bold, creative and utopian minds.” Kennedy was now president. The “despised present” was the Eisenhower administration and the “liberation” from constraints had been accomplished by the inaugural ceremony.

Naturally, feelings about the speech ran high and negative among Eisenhower’s associates, friends, and family. From the Capitol, Eisenhower motored to a farewell reception at the F Street Club hosted by former chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission Admiral Lewis Strauss and attended by the Nixons, my parents, John and Barbara Eisenhower, and former members of the cabinet. During one of the toasts that dwelled sentimentally on Eisenhower and the departed administration, my mother whispered to Nixon seated to her right, “Wasn’t it sad?” Nixon shrugged.

Milton Eisenhower, Eisenhower’s youngest brother and closest confidant, lacking the heart to attend either the inaugu...

David Eisenhower is the Director of the Institute for Public Service at the Annenberg School of Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. He is the author of Eisenhower at War: 1943-1945, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in history in 1987. Educated at Philips Exeter Academy, Amherst College, and George Washington University Law School, he is the son of John and Barbara Eisenhower, and the grandson of President Dwight D. Eisenhower. He is married to the former Julie Nixon, younger daughter of President Richard Nixon. David and Julie Eisenhower are the parents of three adult children and live in suburban Philadelphia.

Julie Nixon Eisenhower is the author of two previous books, Special People and Pat Nixon: The Untold Story.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

Julie Nixon Eisenhower is the author of two previous books, Special People and Pat Nixon: The Untold Story.

GETTYSBURG

GOING HOME

In the late afternoon of Inauguration Day, January 20, 1961, Dwight and Mamie Eisenhower drove north to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in the 1955 Chrysler Imperial that Mamie had purchased for Ike on his sixty-fifth birthday. The outgoing President and First Lady, their personal servants, Sergeant John Moaney and Rosie Woods, and chauffeur, Leonard Dry, sat together in the roomy car. There was an eerie loneliness about the absence of motorcycle escorts and caravans of Secret Service and press cars. A single Secret Service vehicle with driver and agent led the Chrysler. When the Eisenhowers approached the entrance to their Gettysburg farm, the Secret Service honked the horn and made a U-turn, heading back to Washington.

The Eisenhowers’ itinerary had been published in newspapers. Despite a blizzard the night before and below-freezing temperatures, friendly groups in twos and threes lined the road between Washington and Frederick, Maryland. Near Emmitsburg, on Route 15, the crowds grew larger. The nuns, priests, and students of Mount St. Mary’s and St. Joseph’s colleges, bundled in overcoats and scarves, congregated along the road bearing “Welcome Home” signs.

In Gettysburg, a festive mood reigned. Over sixty civic organizations prepared for celebrations scheduled the following evening in the town square welcoming the Eisenhowers home as private citizens. Henry Scharf, owner of the Gettysburg Hotel and host of the “Welcome Home Day” celebration, was pleased that Eisenhower had selected Gettysburg to retire. The Eisenhowers would not only mean tourism, but also add to the historical stature of the community. Scharf, like the majority of the townspeople, had a sense of history about Gettysburg. His study at home was packed with books on the Civil War, World War II, and the American Revolution. By the untidy appearance of his study, one judged he used those references constantly, and he did. He was convinced Eisenhower’s decision to retire to Gettysburg was an affirmation of the town’s historical uniqueness.

As Scharf said to his wife, Peggy, “This is the greatest thing to happen to this town since the battle. This man is beloved by everyone, including his opponents. He is the best-loved president since Lincoln.”

But there was a difference. While in office, Lincoln had been one of the most maligned presidents in American history. His stature had grown with the passage of time and he was linked to Gettysburg by his unforgettable address at the dedication of the National Cemetery. Eisenhower, on the other hand, was perhaps the most popular president while in office, but his reputation might not grow like Lincoln’s, might in fact diminish.

Earlier that morning, Scharf’s daughter, Elise, scurried about her Alexandria, Virginia, apartment collecting a few necessities for the journey to Gettysburg along the precise route the Eisenhower party would take. Not only was Elise needed at home to assist with the multicourse dinner arrangements; she also eagerly anticipated a chance to see the Eisenhowers close-up and perhaps even to chat. Elise admired President Eisenhower and had seen him from a distance on the few occasions her father’s staff had been involved in catering functions on the grounds of the Gettysburg farm. She had gone along as a member of the kitchen or grounds crew, just for a glimpse. Now, as far as she and several thousand other Gettysburgians were concerned, the Eisenhowers were becoming neighbors. Nobody planned to bother them or to ask them to appear at social gatherings and club functions. Everyone expected that eventually the Eisenhowers would take some active part in the community, but no one would impose.

The weather was ominous. Elise worried that she would be blocked by the accumulating snowdrifts, which were paralyzing the capital city and the roads leading to southern Pennsylvania. Snow had fallen heavily the night before, and the entire Potomac Basin was frozen. Temperatures had plummeted. As the ceremonies inaugurating John Kennedy as the thirty-fifth president drew to a conclusion, Elise called the Maryland State Police to learn the status of the northbound roads. She found out that nothing could be guaranteed after three o’clock but that if she left immediately, she had a reasonable chance of getting home.

Additionally, she reasoned, if she could reach Route 15 at Frederick, the remainder of the road running through Thurmont and Emmitsburg would be kept open for the Eisenhower motorcade. Elise set off on her uncertain trek and eventually joined up five minutes behind the bittersweet Eisenhower procession.

Every mile, Elise saw evidence that the Eisenhower motorcade had passed through minutes before. She saw discarded signs reading “Welcome Home,” and the dispersing throngs who moments earlier had braved the cold to ease Eisenhower’s transition to private life. In Emmitsburg, Peggy passed the congregation of nuns packing up blankets and signs outside of St. Joseph’s College. Upon arriving in Gettysburg, she learned of improving forecasts for the 21st, calling for frigid weather but gradually diminishing snowfall. The ceremonies set for the next day were on.

———

At dinnertime, my grandparents drove directly to our home, a former schoolhouse that stood on the corner of their farm. My three younger sisters, Anne, eleven, Susan, nine, Mary Jean, five, and I, now a grown-up twelve years old, had watched the inauguration at home in Gettysburg. I remembered thinking that it should have been the Nixons moving into the White House—and then thinking that being twelve and fourteen years old, the ages of Julie and Tricia Nixon, would be a terrible time to have Secret Service agents. I would miss the men on my detail, but not their constant guarding of Gran One, Gran Two, Gran Three, and Gran Four, the official Secret Service names for my sisters and me.

Everyone now seemed animated and happy, in sharp contrast to the air of numbing tension in the White House several weeks earlier. Relaxed, Granddad listened intently to every word spoken and seemed to say less than usual. He basked in the attention, joking lightly. Characteristically, he wandered frequently into the kitchen to supervise dinner preparations by Sergeant Moaney and his wife, Delores, who had arrived at the farm earlier in the day. Moaney had joined Granddad’s staff as his orderly in the early months of the war in Europe and Delores had become my grandparents’ cook after the war.

My father, John, broke the spell of gaiety toward the end of the evening, standing up from the dinner table to speak. He reviewed briefly Granddad’s accomplishments and then spoke of the years before the fame. As a small, tight-knit family of three, the Eisenhowers had seen much of the world. They had lived in Paris and in Washington both before and during the Depression. They then went on to the Philippines and four years of service under General Douglas MacArthur. The war had dispersed the family, John going to West Point, Mamie returning to Washington, and Dwight Eisenhower going on, in Douglas MacArthur’s words, to “write his name in history.” Dad recalled that the decision to run for president had been difficult, but in the end, Dwight Eisenhower had returned from his NATO command to lead the country through eight years of peace and prosperity. Dad spoke of the experience of a lifetime he had had serving his father in the West Wing.

“Leaving the White House will not be easy at first,” Dad said. “But we are reunited as a family, and this”—Dad gestured to all of us seated, and outside toward the farm—“is what we have wanted. I suppose that tonight, we welcome back a member of this clan who has done us proud.” Dad raised his glass in a toast.

Too moved to reply, Granddad simply held his glass high and joined in the “hear, hear.”

———

It had been a long day. Earlier, Eisenhower had transferred power to John F. Kennedy. That morning, after coffee at the White House and a brief pause at the North Portico for the benefit of newsmen, photographers, and television cameras, Eisenhower and Kennedy had driven off to the Capitol wearing top hats in place of the homburgs that Eisenhower had sought to install as a tradition at his inaugural in 1953. The tradition, Time noted, “will end with his [Eisenhower’s] administration.”

Slowly the black limousine bearing the oldest and second-youngest presidents in U.S. history had rolled toward the gleaming Capitol building, past the crowd estimated at nearly a million people lining Washington’s broad boulevards and gradually filling the newly installed tiers of spectator’s stands. In December, Eisenhower had ruefully likened the stands appearing around the White House and along the inaugural parade route to “scaffolds.” By that comment Eisenhower might have been mindful of his inauguration eight years earlier. After he and Harry Truman exchanged only a few words during the entire ceremony, Truman’s departure, in Eisenhower’s mind, had taken on the character of a hanging. But in January 1961, Harry Truman, busy making the rounds of inaugural parties, appeared to have forgotten the affair. On the 19th, Truman told reporters he had “no advice” regarding Eisenhower’s retirement, adding that as far as he was concerned, Eisenhower was “a very nice person.”

Eisenhower was being handled gently, even affectionately, as he went through the ritual of laying down power. Since November, Kennedy had been at his cordial best. Before the inaugural ceremony, Eisenhower and Kennedy had chatted amicably in the Red Room. For his part, Kennedy was almost alight with the intense media excitement over his ascension to power.

Eisenhower had been busy in January preparing his final messages to the American people. In his eighth State of the Union address, he declared the state of the union to be sound. He reminded the country that for eight years Americans had “lived in peace.” Eisenhower listed his administration’s measures that had ensured the peace: the ballistic missile program, strong support for foreign aid, a series of alliances ringing the Sino-Soviet landmass, and efforts to open talks between East and West. Two weeks later, in his farewell address to the nation, Eisenhower had expressed forebodings about the domestic implications of a permanent state of mobilization without war, warning that a “military industrial complex” could undermine democratic self-rule.

But Eisenhower’s message fell on deaf ears. The inaugural coincided with a period of turmoil. Nikita Khrushchev in early January issued an ominous declaration. Aimed partly at China, partly at the United States, he endorsed “wars of national liberation,” a program of Soviet support for insurgencies and sabotage worldwide against the remnants of Western colonialism. In Laos, North Vietnamese battalions operated with Pathet Lao units in a battle against pro-Western forces for control of the strategic Plain of Jars. In Cuba, Fidel Castro paraded Soviet-built tanks and Cuban militiamen through downtown Havana, proclaiming his preparedness against a rumored invasion from the north. In France, voters approved a referendum endorsing Charles de Gaulle’s program to end the war in Algeria, setting the stage for France’s capitulation to the rebel forces. Throughout Belgium, half a million workers, teachers, and businessmen protested the government’s austerity program, enacted because of the wrenching loss of the Congo and the end of colonialism in Africa.

Kennedy disagreed with Eisenhower’s optimism about the state of the union and now it was his turn to speak. In January, the president-elect had proclaimed before the Massachusetts legislature that his government would “always consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill—the eyes of all the people are upon us.” Now center stage, on the threshold of assuming the presidency, Kennedy wanted to convey a sense of urgency, to “rekindle the spirit of the American revolution,” and to ask for greater exertions by the American people. In New York on September 14, he had declared his presidency would be “a hazardous experience,” predicting, “We will live on the edge of danger.”

Minor mishaps enriched the pageantry of the Kennedy inaugural. Cardinal Cushing’s invocation was interrupted by a short circuit in the electric motor powering the heating system that warmed the seated dignitaries. Mamie Eisenhower first noticed the smoke and for several awkward moments the assembled officials on the platform scurried about in confusion. The winter sun’s glare temporarily blinded poet Robert Frost at the lectern, and forced him to recite from memory a poem he had published in 1942 titled “The Gift Outright,” rather than the poem he had written for the inaugural.

Following the administration of the oath, Kennedy delivered the most memorable inaugural speech since Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s in 1933. The young president achieved eloquence, an inspirational quality, a tone of defiance and resolve. He repudiated the confident premise of the Eisenhower administration. “Only a few generations,” he declared, “have been granted the role of defending freedom in its hour of maximum danger. I welcome this responsibility.”

Kennedy drew attention to his youth and to his awareness that this was a moment of transition from wartime to postwar leadership.

We dare not forget today that we are the heirs of that first revolution. Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch is passed to a new generation of Americans—born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage—and unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this nation has always been committed, and to which we are committed today, at home and around the world.

To Khrushchev’s promise to subsidize “wars of national liberation,” Kennedy replied:

Let every nation know whether it wishes us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend or oppose any foe to assure the survival and success of liberty. This much we pledge and more.

Implying years of inaction under Eisenhower, he cried: “But let us begin . . . let us begin anew.”

The Los Angeles Times noted about Kennedy: “He is wrong in implying the beginning came with him, but he is right in suggesting that the perfecting of mankind is tedious and unpredictable.” But Time magazine had applauded Kennedy’s “lean, lucid phrases,” noting his message had “profound meaning for the US future.”

Fourteen years later, author Robert Nisbet, criticizing the liberals’ fondness for crisis, wrote that “crisis is always an opportunity for a break with the despised present, liberation from the kinds of authority which are most repugnant to bold, creative and utopian minds.” Kennedy was now president. The “despised present” was the Eisenhower administration and the “liberation” from constraints had been accomplished by the inaugural ceremony.

Naturally, feelings about the speech ran high and negative among Eisenhower’s associates, friends, and family. From the Capitol, Eisenhower motored to a farewell reception at the F Street Club hosted by former chairman of the Atomic Energy Commission Admiral Lewis Strauss and attended by the Nixons, my parents, John and Barbara Eisenhower, and former members of the cabinet. During one of the toasts that dwelled sentimentally on Eisenhower and the departed administration, my mother whispered to Nixon seated to her right, “Wasn’t it sad?” Nixon shrugged.

Milton Eisenhower, Eisenhower’s youngest brother and closest confidant, lacking the heart to attend either the inaugu...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherThorndike Press

- Publication date2011

- ISBN 10 1410434389

- ISBN 13 9781410434388

- BindingHardcover

- Number of pages597

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 64.00

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Going Home to Glory: A Memoir of Life with Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1961-1969 (Thorndike Press Large Print Biography)

Published by

Thorndike Press

(2011)

ISBN 10: 1410434389

ISBN 13: 9781410434388

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: New. Seller Inventory # Abebooks400140

Buy New

US$ 64.00

Convert currency