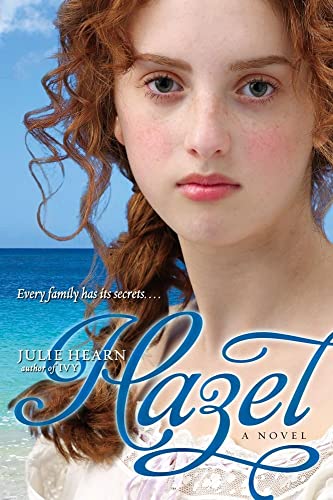

Items related to Hazel: A Novel

Hazel Louise Mull-Dare has a good life, if a bit dull. Her adoring father grants her every wish, she attends a prestigious school for the Daughters of Gentlemen, and she receives no pressure to excel in anything whatsoever. But on the day of the Epsom Derby—June 4th, 1913—everything changes. A woman in a dark coat fatally steps in front of the king's horse, protesting the injustice of denying women the vote. Hazel is transfixed. And when her bold American friend, Gloria, convinces her to stage her own protest, Hazel gets a taste of rebellion. But her stunt leads to greater trouble than she could have ever imagined—Hazel is banished from London to her family’s sugar plantation in the Caribbean. There she is forced to confront the dark secrets of her family—secrets that have festered—and a shame that lingers on.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

The Times

Thursday, June 5, 1913

A MEMORABLE DERBY

The desperate act of a woman who rushed from the rails onto the course as the horses swept round Tattenham Corner, apparently from some mad notion that she could spoil the race, will impress the general public even more, perhaps, than the disqualification of the winner. She did not interfere with the race, but she very nearly killed a jockey as well as herself, and she brought down a valuable horse. She seems to have run right in front of Anmer, which Herbert Jones was riding for the king. It was impossible to avoid her . . .

Thump!

Hazel lowered the newspaper and held her breath. She had never been forbidden, exactly, from entering her father’s study, or from reading the Times . But she knew it would look bad if she was caught.

Thump! Thump!

It was Florence, sweeping the stairs. Florence was all right, and probably wouldn’t tell. Only she might mention it to Mrs. Sawyer, the housekeeper, who was a bitter old fright and probably would.

Quickly, in case the door should suddenly open, Hazel read on:

Some of the spectators close to the woman supposed that she was under the impression that the horses had all gone by and was merely attempting to cross the course. The evidence, however, is strong that her action was deliberate and that it was planned and executed in the supposed interests of the suffragist movement. Whether she intended to commit suicide, or was simply reckless, is hard to surmise. . . .

“Are you there, sir? May I come in?”

Oh, fiddle!

Quickly Hazel skimmed a few more lines:

She is said to be a person well known in the suffragist movement, to have had a card of a suffragist association upon her, and to have had the so-called “Suffragist Colors” tied round her waist. . . .

“Sorry, sir, I’ll—Oh! Miss Hazel, it’s you. You frightened me half to death.”

Annoyed, Hazel folded her father’s copy of the Times and put it back on his desk. Alive, then. The trampled woman was still alive. And it had been deliberate. She’d been right about that.

“I needed something,” she said, her face turning very pink. It wasn’t a lie, for she had needed something—information. All the same, it was agony to say it.

She expected Florence to go. To say that she would come back later. It was rotten luck to have been caught red-handed but inevitable, really, given the number of servants in the house and the way they constantly milled around with their dustpans and flyswatters and the stuff they used to clean the carpets when one of the dogs had a mishap.

Florence, however, showed no signs of leaving. Instead she put down her dustpan and began flicking a feather duster at things.

“No school today, miss?” she asked brightly.

“No,” said Hazel. “I am indisposed.”

It wasn’t the Done Thing to mention bodily functions—particularly those of a feminine nature—to anyone . But Hazel didn’t care, for she had only told the truth.

Serves you right for asking, she thought, as Florence flicked faster to cover her embarrassment. And really, it was ridiculous—wasn’t it?—that feminine things were never to be discussed, not even discreetly between two grown girls, when there were dogs leaving evidence of their own bodily functions on every stair and landing.

Florence began dusting a framed photograph of Hazel’s mother. It was already clean enough to glint, but Florence dusted it anyway, her eyes fixed devotedly on the face behind the glass. Hazel was familiar with this look of adoration. It softened her father’s features every night at dinner. And she had seen it all her life in the rheumy eyes of assorted greyhounds, spaniels, and mongrels, whenever they heard a latch click and her mother’s voice calling out their names.

It was a peculiar look, Hazel decided. Hungry, almost. She could forgive it in her father, and dumb animals couldn’t help themselves, but this girl, presumably, had a mother of her own to dote on, so she should leave other people’s alone.

“Florence,” she said, “do you know what a suffragist is?”

Florence stopped what she was doing and stared at Hazel in surprise. Not devotion. Just surprise.

“A suffering what, miss?”

“A suff-ra-gist,” Hazel repeated patiently. “They are . . . special people, I believe. Women.”

“Do you mean them doolally women, miss? The ones what want the Vote?”

Hazel shrugged. Maybe she did. Maybe she didn’t. She knew what the vote was, though, for her father had one, which he had used a few years back to try and keep Mr. Asquith from becoming the prime minister and sending the country to Rack and Ruin.

Florence lifted an ebony statuette and gave the desk beneath it a cursory tickle with the duster. “Careful,” said Hazel automatically, for the black statuette, of an ancient goddess called Isis, was both lovely and rare, and one of her father’s most treasured possessions.

“You don’t want to be bothering about them kinds of women, miss,” Florence said, replacing the ebony Isis just so. “They’re as mad as March hares, according to Cook. She says there’s one in particular tore up all the orchids in Kew Gardens the other week. Imagine that! Ripped them clean out their tubs in great big handfuls she did, shouting ‘Votes for women!’ all the while. And there’s been windows smashed and all sorts. And what for? Let the men run the country, is what Cook says. We womenfolk have other cats to skin.”

She sniffed derisively, dusted a brass letter rack, and looked around for something else to clean.

Hazel watched, uncertain how to proceed with this interesting conversation. It was doubtful that Florence had ever been to school. Almost certainly she wouldn’t be able to read the Times. And yet she clearly knew plenty—far more than Hazel, anyway—about the ways of the world.

“I would be interested to meet a suffragist,” she said. “Do you know where I might find one?”

Florence looked alarmed. “Goodness, no, Miss Hazel,” she exclaimed. “What a question! You’ll find none in this household, that’s for certain. Your father wouldn’t tolerate it, and nor would Mrs. Sawyer.”

What about my mother? Hazel wondered, although she knew well enough that her mother wouldn’t really care if a servant broke a few windows on her afternoons off, so long as she didn’t kick the animals or turn pale at the sight of their excrement.

Florence was cleaning one of the glass-fronted bookcases, standing on tiptoe to sweep the feather duster in wide, ponderous arcs. To Hazel, she looked like a hefty fairy waving a wand. Clap hands if you believe in fairies! Clap hands, children. Everyone clap your hands together, or poor Tinkerbell will die! Hazel had been deliberately sitting on her hands at performances of Peter Pan since she was five years old, so there was nothing whimsical about her image of Florence as a domestic sprite. And instead of smiling to herself she scowled, for there were dictionaries in that bookcase she had planned to consult after finishing the article in the Times .

“Just one more question,” she said to Florence’s broad pinafored back. “If a man calls a woman an ‘invert,’ what does he mean by it?”

Was it her imagination, or did Florence’s spine stiffen? Certainly the feather duster began moving ten times faster, swishing across the bookcase the way the Old Girl’s wipers did whenever rain came bucketing down. Quickly. Urgently. Pushing everything away.

“You’ve got me there, miss,” Florence replied. “I can’t answer that one. Now . . . where’s that pan and brush? If you’ll excuse me, I’ll need to sweep in a moment where your feet are.”

Hazel looked down at her feet, in their soft white shoes. They were very small feet, taking up the tiniest fraction of space on the vast expanse of carpet. From her feet she looked at the Times , which Florence had refolded, and then up at the row of leather-bound dictionaries locked away behind tickled-clean glass.

There is more to know. Much more.

“I have things to do as well,” she said huffily. “So I’d better go and make a start.”

Nothing.

She had nothing whatsoever to be getting on with. Oh, there was a piano to be played, a handkerchief to be embroidered, and a book about a phoenix and a carpet to start reading. There was a rocking horse she could thrash, while pretending to win the Derby, or a collection of seashells to sort through. But none of those things interested her anywhere near as much as staying right here in her father’s study, learning all that the Times and the dictionaries could tell her about the doolally women who wanted the vote.

“Haven’t you forgotten something, miss?”

Pausing in the doorway, Hazel turned.

“Whatever it was that you needed,” said Florence.

Hazel flinched.

“I will come back later,” she snapped.

Up the stairs she went, watching carefully where she trod. Up the stairs to her pink and white bedroom, with its view across Kensington’s rooftops blocked, for the time being, by the leaves of a giant magnolia. One of the maids had been in, to straighten and tidy. The rose-colored bedspread was stretched, tight as skin, over her mattress. A window had been opened, but only a notch, and her silver-backed hairbrush retrieved from a drawer and displayed, like a hint, dead center on the dressing table.

Over in one corner stood a dollhouse, its brick-painted front shut tight and fastened with a big hook and eye. It was a long time since Hazel had played with it; so long that she could no longer remember whether the mother doll was in bed with a headache or down in the kitchen frying miniature eggs in a tiny pan. The father doll, she knew, would be sitting alone in the drawing room. And the little girl doll was hiding in a cupboard.

Sometimes, when she woke in the night, there was moonlight glinting on the dollhouse windows, and she imagined all the little people inside shaking their tiny fists and shouting, “Play with me! Play with me!”

It was the same with the larger dolls. And the teddy bears. And the wooden animals in the ark. She remembered all their names—even the ark’s two ladybirds, though barely bigger than specks, had been given names once upon a time—but the idea of playing with them no longer appealed. And when she thought about them, or caught sight of some of them, propped awkwardly on a shelf, she felt irritated and strangely sad.

Only the rocking horse attracted her still, because if she closed her eyes and held tight to the reins, it was almost like riding a real one. And she could ride it, and ride it, and fancy herself galloping far away . . . to the desert sands of Arabia, or a tropical jungle. Anywhere, really, where she wouldn’t have to eat horrendous things like rice pudding and boiled greens, or embroider stupid bluebirds on ridiculous handkerchiefs, which no one ever blew their noses on because of the bumpy stitches.

The rocking horse was called Spearmint. There it was— SPEARMINT—branded on his neck in black and gold. He’d been named by Hazel’s father after the winner of the 1906 Epsom Derby. Hazel would have preferred something else—a name that didn’t make her think of sweets—but hadn’t been given the choice.

It was warm in the room, despite the opened window. And the light shining in through the magnolia leaves had a bilious tinge. What with the roses on her wallpaper—blowsy pink things, as big as babies’ faces—and the knots of silk flowers decorating the headboard of her bed, it was like being in a conservatory. Or the hothouse at Kew Gardens.

Now there was a good idea for a game.

Her winter coat was in the wardrobe, stinking of mothballs. It wasn’t black, nor did it reach her ankles, but she put it on all the same and buttoned it up to her neck.

How odd it felt to be wearing such a thing on an otherwise ordinary morning in June. Odd and somehow . . . disobedient.

Looking at herself in her full-length mirror, Hazel experienced a rush of warmth that had nothing to do with the mugginess of the day or the weight of her coat. Is this how they feel? she wondered. Her hair looked wrong, though. She couldn’t help the color, any more than she could help the freckles that went with it, but the long looseness of it was childish. She needed hairpins. Her mother would have some, but she didn’t want to be caught, twice in one day, rummaging among her parents’ things.

Lifting the hair in both hands, Hazel twisted it into a loose bun and tied it with a ribbon—a dark ribbon, nothing frivolous. That was better, although it still needed a few pins to keep the bun in place and complete the—aha! Spillikins. There was a box of ivory spillikins among the games on her toy shelf. They would do the job—for now.

And her silk scarf. The green one. Where was it? Shame she didn’t have a mauve one, or a white one either, but she could always make do with hair ribbons, to get the colors right.

Dressing up had never been so much fun.

Downstairs a latch clicked, and the dogs began to bark.

“Pipkin, my darling boy . . . Hello, Rascal. How’s my naughty Rascal, then? Dottie, where are you? Where’s my precious little sweetheart? I’m home!”

Luncheon would be served soon, on the strike of midday, and it would be Cause for Concern, Hazel knew, were she to appear for it dressed for frost and with spillikins in her hair. She had five minutes, at the most, to play her game. Seven, perhaps eight, before Florence or one of the other maids came tapping at her door.

Hazel couldn’t remember whose idea it had been to twine artificial flowers through the rungs of her bedstead, to make the headboard look like a garden trellis. Not hers, certainly. And not Mrs. Sawyer’s, or Florence’s, either, for they called such arrangements dust traps. Anyway, she had never cared for them.

Snip went her nail scissors—such a little sound, but so satisfying. Snip, snip, snip.

How must that suffragist have felt—the one Florence had spoken of—as she destroyed all those valuable orchids at Kew Gardens? Would she have winced a tiny bit, or simply felt triumphant? And although there were no orchids tied to her headboard, there were enough artificial roses and violets and pansies, and enough stupid white things that might or might not have been daisies, to make lopping their heads off a most satisfying act.

Snip . . . snip . . .

There would be salad for lunch, as the day was so warm. A salad of greens. And fresh fruit for dessert, with ice cream if she was lucky and blancmange if she was not.

What would a suffragist eat for lunch?

Anything she wanted.

A banquet . . . a sandwich . . . or nothing at all.

Snip . . .

The trampled woman was still alive. She had done a doolally thing, rushing out like that in front of the king’s horse, but she had done it bravely, and knowingly, so that more people would understand about the vote. About how important it was for women to have it as well as men.

Hazel had never really thought about the vote before. Certainly she hadn’t consciously suffered fro...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherAtheneum Books for Young Readers

- Publication date2010

- ISBN 10 1416925058

- ISBN 13 9781416925057

- BindingPaperback

- Number of pages416

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Hazel: A Novel by Hearn, Julie [Paperback ]

Book Description Soft Cover. Condition: new. Seller Inventory # 9781416925057

HAZEL

Book Description Condition: New. Brand New. Seller Inventory # 1416925058

Hazel

Book Description Paperback / softback. Condition: New. New copy - Usually dispatched within 7-11 working days. Seller Inventory # B9781416925057

Hazel: A Novel

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # V9781416925057

Hazel: A Novel

Book Description Condition: New. Seller Inventory # V9781416925057

Hazel (Paperback)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Paperback. Every family has its secrets. . . . Hazel Louise Mull-Dare has a good life, if a bit dull. Her adoring father grants her every wish, she attends a prestigious school for the Daughters of Gentlemen, and she receives no pressure to excel in anything whatsoever. But on the day of the Epsom Derby--June 4th, 1913--everything changes. A woman in a dark coat fatally steps in front of the king's horse, protesting the injustice of denying women the vote. Hazel is transfixed. And when her bold American friend, Gloria, convinces her to stage her own protest, Hazel gets a taste of rebellion. But her stunt leads to greater trouble than she could have ever imagined--Hazel is banished from London to her family's sugar plantation in the Caribbean. There she is forced to confront the dark secrets of her family--secrets that have festered--and a shame that lingers on. A teen girl in the British Caribbean in 1913 comes face-to-face with the suffragette movement and slavery in Hearn's follow-up to "Ivy." Shipping may be from our Sydney, NSW warehouse or from our UK or US warehouse, depending on stock availability. Seller Inventory # 9781416925057

Hazel (Paperback)

Book Description Paperback. Condition: new. Paperback. Every family has its secrets. . . . Hazel Louise Mull-Dare has a good life, if a bit dull. Her adoring father grants her every wish, she attends a prestigious school for the Daughters of Gentlemen, and she receives no pressure to excel in anything whatsoever. But on the day of the Epsom Derby--June 4th, 1913--everything changes. A woman in a dark coat fatally steps in front of the king's horse, protesting the injustice of denying women the vote. Hazel is transfixed. And when her bold American friend, Gloria, convinces her to stage her own protest, Hazel gets a taste of rebellion. But her stunt leads to greater trouble than she could have ever imagined--Hazel is banished from London to her family's sugar plantation in the Caribbean. There she is forced to confront the dark secrets of her family--secrets that have festered--and a shame that lingers on. A teen girl in the British Caribbean in 1913 comes face-to-face with the suffragette movement and slavery in Hearn's follow-up to "Ivy." Shipping may be from our UK warehouse or from our Australian or US warehouses, depending on stock availability. Seller Inventory # 9781416925057