Items related to Alexander McQueen

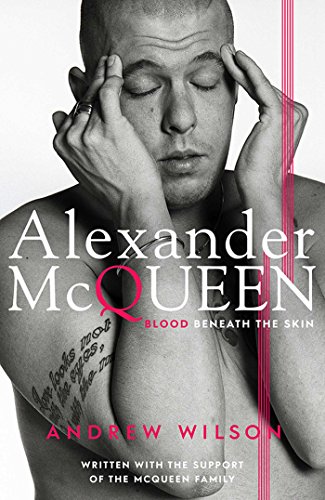

The definitive biography of Alexander McQueen which reveals the source of his genius and the links between his dark work and even darker life.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author:

Andrew Wilson is the highly acclaimed author of biographies of Patricia Highsmith, Sylvia Plath and Alexander McQueen. His first novel, The Lying Tongue, was published in 2007. His journalism has appeared in the Guardian, the Daily Telegraph, the Observer, the Sunday Times, the Daily Mail and the Washington Post.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.:

Alexander McQueen CHAPTER ONE

A history of “much cruelty and dark deeds.”

—Joyce McQueen

When Lee Alexander McQueen was born, on 17 March 1969 at Lewisham Hospital in southeast London, he weighed only five pounds ten ounces. The doctors told his mother, Joyce, that his low weight could mean that he might have to be placed in an incubator, but he soon started to feed, and mother and baby returned home to the crowded family home at 43 Shifford Path, Wynell Road, Forest Hill. Although Joyce and Ron, in the words of their son Tony, “always said that he [Lee] was the only one they tried for,” the birth of the youngest of their six children did nothing to soothe the tense atmosphere in the McQueen household.

“My dad had a breakdown in 1969, just as my mum gave birth,” said Lee’s brother Michael McQueen. “He was working too hard, a lot of hours as a lorry driver with six children, too many really.”1 His brother Tony, who was fourteen years old at the time, remembers noticing that one day his father went unnaturally quiet. “He was working seven days a week, he was hardly ever home,” said Tony. “My mum got someone round and they institutionalized him. It was a difficult period for us.” Joyce, in an unpublished manuscript she compiled for the family, noted that her husband spent only three weeks in Cane Hill Hospital, Coulsdon, but according to Tony, “Dad had a nervous breakdown and he went into a mental institution for two years.”2

Cane Hill Hospital was the archetypal Victorian asylum, an enormous rambling madhouse of the popular imagination. Designed by Charles Henry Howell, it was originally known as the Third Surrey County Pauper Lunatic Asylum, so called because the county’s other two institutions, Springfield and Brookwood, had reached full capacity. “Cane Hill was typical of its time, providing specialized wards for different categories of patients, with day rooms on the ground floor and dormitories and individual cells mostly on the second and third floors,” wrote one historian. “Difficult patients were confined to cells and those of a more clement disposition could walk the airing grounds . . . By the 1960s, the hospital had changed little.”3 Former patients included Charlie Chaplin’s mother, Hannah, and the half brothers of both Michael Caine and David Bowie, who used a drawing of the administration block on the American cover of his 1970 album The Man Who Sold the World.

Lee McQueen was fascinated by the idea of the asylum—he featured the iconography of the madhouse in a number of his collections, particularly Voss (Spring/Summer 2001)—and he would have been intrigued by the rumors about a subterranean network of tunnels near Cane Hill. Over the years it has been suggested that the series of brick-lined tunnels housed a mortuary, a secret medical testing facility and a nuclear bomb shelter. Although the truth was much more mundane—the tunnels were built as bomb shelters during the Second World War and then taken over by a company that manufactured telescopes—the network of underground chambers “became somehow connected with the institution and the obscure rusting of machinery took on sinister new overtones, driven by the superstition surrounding the complex.”4

Years after the closure of Cane Hill, a couple were walking around the grounds of the hospital when, in the Garden House, they came across a bundle of faded yellow pages, remnants of the kind of questionnaire Ronald McQueen would have encountered while a patient at the institution. Many of the fifty-one questions, which patients were encouraged to answer with a response of “true” or “false,” would have had a particular resonance if they had later been applied to Lee: “I have not lived the right kind of life,” “Sometimes I feel as if I must injure myself or someone else,” “I get angry sometimes,” “Often I think I can’t understand why I have been so cross and grouchy,” “I have sometimes felt that difficulties were piling up so high that I could not overcome them,” “Someone has it in for me,” “It is safer to trust nobody,” and “At times I have a strong urge to do something harmful or shocking.”5

It’s difficult to know the exact effect of Ronald’s breakdown on his youngest son. A psychotherapist might be able to draw links between Lee’s later mental health issues and his father’s illness. Did Lee come to associate his birth, his very existence, with madness? Did the boy feel some level of unconscious guilt for driving his father into a psychiatric ward? There is no doubt, however, that in an effort to comfort both her infant son and herself, Joyce lavished increased levels of love on Lee and, as a result, the bond between them intensified. As a little boy, Lee had a beautiful blond head of curls, and photographs taken at the time show him to be an angelic-looking child. “He had preferential treatment from my mother but not my dad; he was a bit Neanderthal because of his hard upbringing,” said Michael McQueen.6

When Lee was less than a year old the family moved from south London to a council house in Stratford, a district close to the dock area of east London. “I think if you’re from the East End you can’t get used to the south side,” said Lee’s sister Janet McQueen. “They say you can’t move an old tree and it was like that. I think it was probably that a housing initiative came up and we had the chance of moving into a house, a new house.”7 The council house, at 11 Biggerstaff Road, was a three-story brick terraced house and although it had four bedrooms it was still a squeeze for the family. “We boys slept three to a bed in there,” said Tony McQueen. “My mum would say, ‘Which end would you like?’ and I would say, ‘The shallow end; Lee keeps pissing himself.’ ”8 Family photos show that the house was a typical modern working-class home with a fitted patterned carpet, floral sofas with wooden arms, papered walls and gilt-framed reproductions of paintings by Constable. At the back of the house there was a small paved garden with a raised fishpond and a white gate that led out onto a grassy communal area in front of a tower block.

Ron couldn’t work because of his condition, and money was in short supply. Janet left school at fifteen and took a job in London Bridge in the offices of a dried egg import business to help support the family. Her brother Tony recalls how difficult it was for the family to survive. “My mum would give me the money to go on the bus to where Janet was working, to get her wages off her, and then I would bring the money back to my mum and meet her and do the shopping with her,” he said. “Mum was working as well, doing cleaning in the morning and the evening.”9

When Ron returned from Cane Hill to the house in Stratford, he trained to become a black-cab driver so he could work the hours that suited him. He had, in Joyce’s words, “wonderful willpower to get better again.”10 He took up fishing and snooker and finally started to earn a little more money. Life in 1970s Britain was, for many ordinary families like the McQueens, a rather grim affair. In 1974 there were two general elections and the country was gripped by economic and social unrest. Power cuts were a regular feature of daily life (a three-day weekly limit for the commercial consumption of electricity had been imposed), rubbish went uncollected for weeks and unemployment surged past the all-important one million mark (by 1978 it stood at 1.5 million).

Yet the work ethic was strong in the McQueen family—Ron eventually bought the house from the council in 1982—and he expected his sons to get steady and reliable jobs as plumbers, electricians, bricklayers or cabdrivers. The upbringing was strict, almost Victorian. If he saw his children “getting beyond or above themselves,” he would try and bring them back down to earth, quashing their confidence in the process. “We were seen and not heard,” said Lee’s sister Jacqui.11 By the time Tony was fourteen he had traveled all over the country with Ron in a lorry. “So my education suffered a bit,” he said. “That was me and Michael’s childhood.”12 Tony left school to work as a bricklayer and Michael became a taxi driver like his father. They were born into the working classes and their father believed that any aspiration above and beyond that would not only lead to personal unhappiness and dissatisfaction but would serve as a betrayal of their roots too. Creativity in any form was frowned upon and regarded as a total waste of time; dreaming was all well and good but it would not put food on the table.

It was into this world that Lee, a sensitive, bright child with a vivid imagination, was born. From the very beginning the cherubic-looking boy strived for something more, a desire that he found he could express through the medium of clothes. When he was three he picked up a crayon lying around his sisters’ bedroom and drew an image of Cinderella, “with a tiny waist and a huge gown,” on a bare wall.13 “He told me about that Cinderella drawing on the wall, I thought it was quite magical,” said his friend Alice Smith, who visited the house in Biggerstaff Road a number of times. “I also remember him telling me about how one day his mum dressed him up to go out when he was little. He was wearing trousers with an anorak and they were going to the park and he said, ‘Mum, I can’t wear this.’ She asked him why not and he replied, ‘It doesn’t go.’ ”14 His sisters started to ask him about what they should wear to work and he soon became their “daily style consultant.” “I was absorbed early on by the style of people, by how they expressed themselves through what they wear,” he said.15

When Lee was three or four he was playing by himself at the top of the house in a bedroom that looked out towards Lund Point, a twenty-three-story tower block behind the terrace. He climbed onto a small ottoman that sat beneath the window and pushed the window wide open. Just as he was stretching out to reach through the window his sister Janet walked into the bedroom. “The window had no safety catch and he was stood on the ottoman reaching out,” she said. “I thought to myself, ‘No, don’t say anything.’ I went up behind him and grabbed him. I probably told him off because he could easily have fallen out of the window.”16 He was, by all accounts, a mischievous, spirited little boy. He stole his mother’s false teeth and put them in his mouth for a joke or repeated the same trick with a piece of orange peel cut into jagged, teeth-like shapes. He would take hold of his mother’s stockings and pull them over his head to frighten people. With his sisters he would go along to the local swimming club to take part in synchronized-swimming competitions. “You would hear our trainer, Sid, shouting, ‘Lee—Lee McQueen?’ and he would be under the water looking at us,” said Jacqui. “Or he would have a hula skirt on and suddenly jump into the water. He was so funny.”17 One day, Lee did a backflip off the side of the swimming pool and hit his cheekbone, an accident that left him with a small lump.

After Lee and Joyce’s deaths her treasured photograph albums were passed around between her remaining five children. Seeing images of Lee as a boy, looking bright-eyed and full of fun, was especially hard for the McQueens. Here was Lee with a swathe of white fabric around his head, his right foot wrapped in a bandage, his left eye smudged with makeup so as to give him a black eye, and a cane in one hand and a box of chocolates in the other; around his neck hangs the sign “All Because the Lady Loved Milk Tray.” There are plenty more taken at similar holiday camp competitions—one of him holding a prize while staying at Pontins and another of him, when he was only three or so, dancing with a little girl the same age, his blond hair falling down the side of his head, his mouth open wide with joy. There is one of him enjoying being picked up and cuddled by a man in a panda suit and another of him looking a little more self-conscious, probably a photograph taken at junior school, trying to smile but careful to keep his mouth closed because he did not want his prominent and uneven front teeth to show. One day when Lee was a young boy he tripped off the small wall in the back garden of the house in Biggerstaff Road and hit his teeth. “He was always self-conscious about his teeth after that,” said Tony.18 “I remember he had an accident when he was younger and lost his milk teeth and the others came through damaged or twisted,” said Peter Bowes, a school friend who knew him from the age of five. “So he had these buck front teeth, one of the things that would give him a reason to be humiliated and picked on. He was called ‘goofy’ and things like that.”19

Lee knew that he was not like other boys from an early age, but the exact nature and source of this difference were still unclear to him. His mother picked up the fact that her youngest son was a strange mix of surface toughness and unusual vulnerabilities and did everything she could to protect him. “He was this little fat boy from the East End with bad teeth who didn’t have much to offer, but he had this one special thing, this talent, and Joyce believed in him,” said Alice Smith. “He told me once that she had said to him, ‘Whatever you want to do, do it.’ He was adored; they had a special relationship, it was a mutual adoration.”20

· · ·

When Lee was a boy he would watch in wonder as his mother unrolled an eight-foot-long scroll decorated with elaborate coats of arms. She would point out the names of long-dead ancestors on the family tree and talk about the past. Joyce was passionate about genealogy—she later taught the subject at Canning Town Adult Education Centre—and she told her young son that she suspected that the McQueen side of the family had originated from the Isle of Skye. Lee had become increasingly fascinated with the island’s gothic history and his ancestors’ place in it. It was on a holiday with Janet in 2007 that he first visited the small cemetery in Kilmuir—the last resting place of the Jacobite heroine Flora MacDonald—and saw a grave marked with the name Alexander McQueen; in May 2010, the designer’s cremated remains were buried in the same graveyard.

Joyce spent years plotting out the family tree, but by the end of her research she had failed to find any definitive evidence linking her husband’s McQueen ancestors to Skye. But, like many things in Lee’s life, the romance of the idea was more alluring than the reality. Listening to his mother’s tales of Scotland’s brutal history, and the suffering that his ancestors endured at the hands of the English landowners, he constructed an imaginative bloodline across the centuries. One of the attractions of boyfriend Murray Arthur was the fact that he was from north of the border. “He was obsessed by Scotland, and loved the fact that I was Scottish,” he said.21 Lee’s bond with Scotland grew increasingly strong over the years—it inspired collections such as Highland Rape (1995) and Widows of Culloden (2006)—and in 2004, when his mother asked him what his Scottish roots meant to him, McQueen replied, “Everything.”22

Joyce McQueen’s journey back into the past started when her husband asked her to find out about the origins of his family: “Are we Irish or Scottish?” By 1992, she had gathered her work into a manuscript that told the story of the McQueens’ roots. “Researching family history can be fun, but more than this it can give us a sense of belonging and how we came to be,” wrote Joyce.23 For Lee, this was especially important as it provided him with a connection to history and opened up possibilities that allowed his imagination to fly.

Joyce noted how the earliest mention of the name McQueen on the Isle of Skye was in the fourtee...

A history of “much cruelty and dark deeds.”

—Joyce McQueen

When Lee Alexander McQueen was born, on 17 March 1969 at Lewisham Hospital in southeast London, he weighed only five pounds ten ounces. The doctors told his mother, Joyce, that his low weight could mean that he might have to be placed in an incubator, but he soon started to feed, and mother and baby returned home to the crowded family home at 43 Shifford Path, Wynell Road, Forest Hill. Although Joyce and Ron, in the words of their son Tony, “always said that he [Lee] was the only one they tried for,” the birth of the youngest of their six children did nothing to soothe the tense atmosphere in the McQueen household.

“My dad had a breakdown in 1969, just as my mum gave birth,” said Lee’s brother Michael McQueen. “He was working too hard, a lot of hours as a lorry driver with six children, too many really.”1 His brother Tony, who was fourteen years old at the time, remembers noticing that one day his father went unnaturally quiet. “He was working seven days a week, he was hardly ever home,” said Tony. “My mum got someone round and they institutionalized him. It was a difficult period for us.” Joyce, in an unpublished manuscript she compiled for the family, noted that her husband spent only three weeks in Cane Hill Hospital, Coulsdon, but according to Tony, “Dad had a nervous breakdown and he went into a mental institution for two years.”2

Cane Hill Hospital was the archetypal Victorian asylum, an enormous rambling madhouse of the popular imagination. Designed by Charles Henry Howell, it was originally known as the Third Surrey County Pauper Lunatic Asylum, so called because the county’s other two institutions, Springfield and Brookwood, had reached full capacity. “Cane Hill was typical of its time, providing specialized wards for different categories of patients, with day rooms on the ground floor and dormitories and individual cells mostly on the second and third floors,” wrote one historian. “Difficult patients were confined to cells and those of a more clement disposition could walk the airing grounds . . . By the 1960s, the hospital had changed little.”3 Former patients included Charlie Chaplin’s mother, Hannah, and the half brothers of both Michael Caine and David Bowie, who used a drawing of the administration block on the American cover of his 1970 album The Man Who Sold the World.

Lee McQueen was fascinated by the idea of the asylum—he featured the iconography of the madhouse in a number of his collections, particularly Voss (Spring/Summer 2001)—and he would have been intrigued by the rumors about a subterranean network of tunnels near Cane Hill. Over the years it has been suggested that the series of brick-lined tunnels housed a mortuary, a secret medical testing facility and a nuclear bomb shelter. Although the truth was much more mundane—the tunnels were built as bomb shelters during the Second World War and then taken over by a company that manufactured telescopes—the network of underground chambers “became somehow connected with the institution and the obscure rusting of machinery took on sinister new overtones, driven by the superstition surrounding the complex.”4

Years after the closure of Cane Hill, a couple were walking around the grounds of the hospital when, in the Garden House, they came across a bundle of faded yellow pages, remnants of the kind of questionnaire Ronald McQueen would have encountered while a patient at the institution. Many of the fifty-one questions, which patients were encouraged to answer with a response of “true” or “false,” would have had a particular resonance if they had later been applied to Lee: “I have not lived the right kind of life,” “Sometimes I feel as if I must injure myself or someone else,” “I get angry sometimes,” “Often I think I can’t understand why I have been so cross and grouchy,” “I have sometimes felt that difficulties were piling up so high that I could not overcome them,” “Someone has it in for me,” “It is safer to trust nobody,” and “At times I have a strong urge to do something harmful or shocking.”5

It’s difficult to know the exact effect of Ronald’s breakdown on his youngest son. A psychotherapist might be able to draw links between Lee’s later mental health issues and his father’s illness. Did Lee come to associate his birth, his very existence, with madness? Did the boy feel some level of unconscious guilt for driving his father into a psychiatric ward? There is no doubt, however, that in an effort to comfort both her infant son and herself, Joyce lavished increased levels of love on Lee and, as a result, the bond between them intensified. As a little boy, Lee had a beautiful blond head of curls, and photographs taken at the time show him to be an angelic-looking child. “He had preferential treatment from my mother but not my dad; he was a bit Neanderthal because of his hard upbringing,” said Michael McQueen.6

When Lee was less than a year old the family moved from south London to a council house in Stratford, a district close to the dock area of east London. “I think if you’re from the East End you can’t get used to the south side,” said Lee’s sister Janet McQueen. “They say you can’t move an old tree and it was like that. I think it was probably that a housing initiative came up and we had the chance of moving into a house, a new house.”7 The council house, at 11 Biggerstaff Road, was a three-story brick terraced house and although it had four bedrooms it was still a squeeze for the family. “We boys slept three to a bed in there,” said Tony McQueen. “My mum would say, ‘Which end would you like?’ and I would say, ‘The shallow end; Lee keeps pissing himself.’ ”8 Family photos show that the house was a typical modern working-class home with a fitted patterned carpet, floral sofas with wooden arms, papered walls and gilt-framed reproductions of paintings by Constable. At the back of the house there was a small paved garden with a raised fishpond and a white gate that led out onto a grassy communal area in front of a tower block.

Ron couldn’t work because of his condition, and money was in short supply. Janet left school at fifteen and took a job in London Bridge in the offices of a dried egg import business to help support the family. Her brother Tony recalls how difficult it was for the family to survive. “My mum would give me the money to go on the bus to where Janet was working, to get her wages off her, and then I would bring the money back to my mum and meet her and do the shopping with her,” he said. “Mum was working as well, doing cleaning in the morning and the evening.”9

When Ron returned from Cane Hill to the house in Stratford, he trained to become a black-cab driver so he could work the hours that suited him. He had, in Joyce’s words, “wonderful willpower to get better again.”10 He took up fishing and snooker and finally started to earn a little more money. Life in 1970s Britain was, for many ordinary families like the McQueens, a rather grim affair. In 1974 there were two general elections and the country was gripped by economic and social unrest. Power cuts were a regular feature of daily life (a three-day weekly limit for the commercial consumption of electricity had been imposed), rubbish went uncollected for weeks and unemployment surged past the all-important one million mark (by 1978 it stood at 1.5 million).

Yet the work ethic was strong in the McQueen family—Ron eventually bought the house from the council in 1982—and he expected his sons to get steady and reliable jobs as plumbers, electricians, bricklayers or cabdrivers. The upbringing was strict, almost Victorian. If he saw his children “getting beyond or above themselves,” he would try and bring them back down to earth, quashing their confidence in the process. “We were seen and not heard,” said Lee’s sister Jacqui.11 By the time Tony was fourteen he had traveled all over the country with Ron in a lorry. “So my education suffered a bit,” he said. “That was me and Michael’s childhood.”12 Tony left school to work as a bricklayer and Michael became a taxi driver like his father. They were born into the working classes and their father believed that any aspiration above and beyond that would not only lead to personal unhappiness and dissatisfaction but would serve as a betrayal of their roots too. Creativity in any form was frowned upon and regarded as a total waste of time; dreaming was all well and good but it would not put food on the table.

It was into this world that Lee, a sensitive, bright child with a vivid imagination, was born. From the very beginning the cherubic-looking boy strived for something more, a desire that he found he could express through the medium of clothes. When he was three he picked up a crayon lying around his sisters’ bedroom and drew an image of Cinderella, “with a tiny waist and a huge gown,” on a bare wall.13 “He told me about that Cinderella drawing on the wall, I thought it was quite magical,” said his friend Alice Smith, who visited the house in Biggerstaff Road a number of times. “I also remember him telling me about how one day his mum dressed him up to go out when he was little. He was wearing trousers with an anorak and they were going to the park and he said, ‘Mum, I can’t wear this.’ She asked him why not and he replied, ‘It doesn’t go.’ ”14 His sisters started to ask him about what they should wear to work and he soon became their “daily style consultant.” “I was absorbed early on by the style of people, by how they expressed themselves through what they wear,” he said.15

When Lee was three or four he was playing by himself at the top of the house in a bedroom that looked out towards Lund Point, a twenty-three-story tower block behind the terrace. He climbed onto a small ottoman that sat beneath the window and pushed the window wide open. Just as he was stretching out to reach through the window his sister Janet walked into the bedroom. “The window had no safety catch and he was stood on the ottoman reaching out,” she said. “I thought to myself, ‘No, don’t say anything.’ I went up behind him and grabbed him. I probably told him off because he could easily have fallen out of the window.”16 He was, by all accounts, a mischievous, spirited little boy. He stole his mother’s false teeth and put them in his mouth for a joke or repeated the same trick with a piece of orange peel cut into jagged, teeth-like shapes. He would take hold of his mother’s stockings and pull them over his head to frighten people. With his sisters he would go along to the local swimming club to take part in synchronized-swimming competitions. “You would hear our trainer, Sid, shouting, ‘Lee—Lee McQueen?’ and he would be under the water looking at us,” said Jacqui. “Or he would have a hula skirt on and suddenly jump into the water. He was so funny.”17 One day, Lee did a backflip off the side of the swimming pool and hit his cheekbone, an accident that left him with a small lump.

After Lee and Joyce’s deaths her treasured photograph albums were passed around between her remaining five children. Seeing images of Lee as a boy, looking bright-eyed and full of fun, was especially hard for the McQueens. Here was Lee with a swathe of white fabric around his head, his right foot wrapped in a bandage, his left eye smudged with makeup so as to give him a black eye, and a cane in one hand and a box of chocolates in the other; around his neck hangs the sign “All Because the Lady Loved Milk Tray.” There are plenty more taken at similar holiday camp competitions—one of him holding a prize while staying at Pontins and another of him, when he was only three or so, dancing with a little girl the same age, his blond hair falling down the side of his head, his mouth open wide with joy. There is one of him enjoying being picked up and cuddled by a man in a panda suit and another of him looking a little more self-conscious, probably a photograph taken at junior school, trying to smile but careful to keep his mouth closed because he did not want his prominent and uneven front teeth to show. One day when Lee was a young boy he tripped off the small wall in the back garden of the house in Biggerstaff Road and hit his teeth. “He was always self-conscious about his teeth after that,” said Tony.18 “I remember he had an accident when he was younger and lost his milk teeth and the others came through damaged or twisted,” said Peter Bowes, a school friend who knew him from the age of five. “So he had these buck front teeth, one of the things that would give him a reason to be humiliated and picked on. He was called ‘goofy’ and things like that.”19

Lee knew that he was not like other boys from an early age, but the exact nature and source of this difference were still unclear to him. His mother picked up the fact that her youngest son was a strange mix of surface toughness and unusual vulnerabilities and did everything she could to protect him. “He was this little fat boy from the East End with bad teeth who didn’t have much to offer, but he had this one special thing, this talent, and Joyce believed in him,” said Alice Smith. “He told me once that she had said to him, ‘Whatever you want to do, do it.’ He was adored; they had a special relationship, it was a mutual adoration.”20

· · ·

When Lee was a boy he would watch in wonder as his mother unrolled an eight-foot-long scroll decorated with elaborate coats of arms. She would point out the names of long-dead ancestors on the family tree and talk about the past. Joyce was passionate about genealogy—she later taught the subject at Canning Town Adult Education Centre—and she told her young son that she suspected that the McQueen side of the family had originated from the Isle of Skye. Lee had become increasingly fascinated with the island’s gothic history and his ancestors’ place in it. It was on a holiday with Janet in 2007 that he first visited the small cemetery in Kilmuir—the last resting place of the Jacobite heroine Flora MacDonald—and saw a grave marked with the name Alexander McQueen; in May 2010, the designer’s cremated remains were buried in the same graveyard.

Joyce spent years plotting out the family tree, but by the end of her research she had failed to find any definitive evidence linking her husband’s McQueen ancestors to Skye. But, like many things in Lee’s life, the romance of the idea was more alluring than the reality. Listening to his mother’s tales of Scotland’s brutal history, and the suffering that his ancestors endured at the hands of the English landowners, he constructed an imaginative bloodline across the centuries. One of the attractions of boyfriend Murray Arthur was the fact that he was from north of the border. “He was obsessed by Scotland, and loved the fact that I was Scottish,” he said.21 Lee’s bond with Scotland grew increasingly strong over the years—it inspired collections such as Highland Rape (1995) and Widows of Culloden (2006)—and in 2004, when his mother asked him what his Scottish roots meant to him, McQueen replied, “Everything.”22

Joyce McQueen’s journey back into the past started when her husband asked her to find out about the origins of his family: “Are we Irish or Scottish?” By 1992, she had gathered her work into a manuscript that told the story of the McQueens’ roots. “Researching family history can be fun, but more than this it can give us a sense of belonging and how we came to be,” wrote Joyce.23 For Lee, this was especially important as it provided him with a connection to history and opened up possibilities that allowed his imagination to fly.

Joyce noted how the earliest mention of the name McQueen on the Isle of Skye was in the fourtee...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherScribner

- Publication date2015

- ISBN 10 1471131785

- ISBN 13 9781471131783

- BindingHardcover

- Edition number1

- Number of pages393

- Rating

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

US$ 250.79

Shipping:

US$ 4.30

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Alexander McQueen

Published by

Simon Schuster

(2015)

ISBN 10: 1471131785

ISBN 13: 9781471131783

New

Hardcover

Quantity: 1

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Condition: new. Seller Inventory # FrontCover1471131785

Buy New

US$ 250.79

Convert currency

Alexander McQueen

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Seller Inventory # Wizard1471131785

Buy New

US$ 252.11

Convert currency

Alexander McQueen

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. Seller Inventory # Holz_New_1471131785

Buy New

US$ 253.70

Convert currency

Alexander McQueen

Seller:

Rating

Book Description Hardcover. Condition: new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. Seller Inventory # think1471131785

Buy New

US$ 253.75

Convert currency