Items related to The Last Castle: The Epic Story of Love, Loss, and...

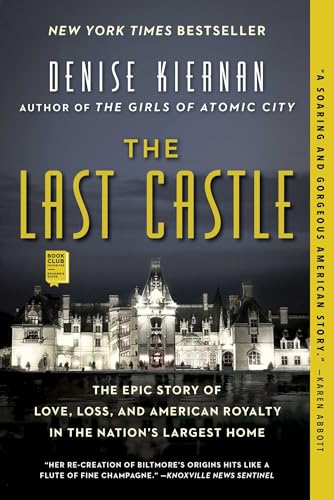

The Last Castle: The Epic Story of Love, Loss, and American Royalty in the Nation's Largest Home - Softcover

Synopsis

A New York Times bestseller with an "engaging narrative and array of detail” (The Wall Street Journal), the “intimate and sweeping” (Raleigh News & Observer) untold, true story behind the Biltmore Estate—the largest, grandest private residence in North America, which has seen more than 120 years of history pass by its front door.

The story of Biltmore spans World Wars, the Jazz Age, the Depression, and generations of the famous Vanderbilt family, and features a captivating cast of real-life characters including F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Wolfe, Teddy Roosevelt, John Singer Sargent, James Whistler, Henry James, and Edith Wharton.

Orphaned at a young age, Edith Stuyvesant Dresser claimed lineage from one of New York’s best known families. She grew up in Newport and Paris, and her engagement and marriage to George Vanderbilt was one of the most watched events of Gilded Age society. But none of this prepared her to be mistress of Biltmore House.

Before their marriage, the wealthy and bookish Vanderbilt had dedicated his life to creating a spectacular European-style estate on 125,000 acres of North Carolina wilderness. He summoned the famous landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted to tame the grounds, collaborated with celebrated architect Richard Morris Hunt to build a 175,000-square-foot chateau, filled it with priceless art and antiques, and erected a charming village beyond the gates. Newlywed Edith was now mistress of an estate nearly three times the size of Washington, DC and benefactress of the village and surrounding rural area. When fortunes shifted and changing times threatened her family, her home, and her community, it was up to Edith to save Biltmore—and secure the future of the region and her husband’s legacy.

This is the fascinating, “soaring and gorgeous” (Karen Abbott) story of how the largest house in America flourished, faltered, and ultimately endured to this day.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Denise Kiernan is the author of The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal bestseller The Last Castle. Her previous book, The Girls of Atomic City, is a New York Times, Los Angeles Times, and NPR bestseller. Kiernan has been published in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Village Voice, Ms., Reader’s Digest, Discover, and many more publications. She has also worked in television, serving as head writer for ABC’s Who Wants to Be a Millionaire during its Emmy award–winning first season and producing for media outlets such as ESPN and MSNBC. She has been a featured guest on NPR’s “Weekend Edition,” PBS NewsHour, MSNBC’s Morning Joe, and The Daily Show with Jon Stewart.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

The Last Castle 1

A Winter’s TaleThat was the year she started spending her winters in New York again.

Edith Dresser was fifteen years old when her grandmother, Susan Elizabeth Fish LeRoy, decided that she and the Dresser children would leave their Rhode Island home for the Christmas season. The year was 1888. Seasonal migrations from Newport to New York were common among their privileged set, and the allure of the great city on the Hudson still drew their grandmother into its predictably casted embrace. Grandmother was a woman at ease in the world of drawing rooms and calling cards, one who appreciated both the ritualistic behaviors and increased social diversions that New York could be counted on to provide. “New Amsterdam”—as Manhattan had once been known—had been home to their family’s Dutch ancestors. Now Grandmother, in turn, had become all that constituted home and family to Edith, her three sisters, and brother.

Grandmother had arranged to rent a house at 2 Gramercy Square, a very respectable—if not ultra-fashionable—address for the family. Its next-door twin, 1 Gramercy, had been the last home of the noted surgeon and professor Dr. Valentine Mott. Mott had helped establish the short-lived Rutgers Medical College in lower Manhattan, and gained attention as the chair of surgery at both the University Medical College of NYU and Columbia’s College of Physicians and Surgeons. More salaciously, he earned some notoriety as a disruptor of all that was good and pure in the world of medical instruction when he promoted the idea of using human cadavers to instruct up-and-coming clinicians. His good works and surgical brilliance kept his reputation intact, even though the good doctor was known to have disguised himself as a laborer and visited graveyards to retrieve recently unearthed teaching aids.

Around the corner on the south side of Gramercy Square, at No. 16, was the brand-new Players Club, which was opening that winter. The building had been purchased by the actor Edwin Booth, who could currently be seen as Brutus in a production of Julius Caesar. Twenty-three years earlier, Booth had announced his retirement following his deranged brother John Wilkes Booth’s assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. Distraught over his brother’s actions, Edwin penned an open letter to “the People of the United States,” which was published in several newspapers:

“For the future alas,” he wrote. “I shall struggle on in my retirement bearing a heavy heart, an oppressed memory and a wounded name—dreadful burdens—to my too welcome grave.”

However, he curtailed his retirement to a nine-month hiatus from the limelight, returning to the stage—and welcome audiences—in 1866 as Hamlet, a role he continued to reprise. The newly founded Players Club would house an impressive library of theater history, as well as collections of paintings and autographs. Booth wrote a friend that he wanted the club to “be a place where actors are away from the glamour of the theatre,” and that thespians should spend more time mingling with minds that “influence the world.” To that end, founding members of the club included author Mark Twain and the celebrated Union Army general William Tecumseh Sherman.

2 Gramercy Square, where young Edith and her family would be staying, was the home of the Pinchot family—businessman James Wallace Pinchot; his wife, Mary Jane Eno Pinchot; and their children, Gifford, Amos, and Antoinette. The Pinchot family had recently completed the building of a new Milford, Pennsylvania, home that had been designed by the noted New York City architect Richard Morris Hunt and subsequently dubbed “Grey Towers.” The Pinchots’ oldest son, Gifford, was away studying at Yale, and Edith and her sisters knew “Nettie” Pinchot from dancing class in Newport. The four-story brick house was Italianate in style, with cast-iron railings gracing its small balconies and floor-to-ceiling parlor windows. Edith’s brother, Daniel—who went by his middle name “LeRoy”—was in his final year at Columbia, which meant that he would again be living under the same roof as his sisters. Susan, the oldest, was now twenty-four, and two years older than LeRoy. Natalie was nineteen and Pauline, the baby, was still just twelve. The family would be together, nestled in this house across from the gated park.

From outside those parlor windows looking in, one might have seen four young ladies and one young man living the kind of gleaming nineteenth-century life envied by scores of less fortunate citizens of the time. A closer inspection of their lives, however, revealed signs of difficulty and strain, like scuff marks hidden beneath the smooth veneer of a freshly polished parlor floor. They were five siblings, separated in age by twelve years; joined, as so many other families of the time were, by tragic loss.

· · ·

Edith’s parents had met at West Point, New York, where her father was a cadet and her mother, Susan Fish LeRoy, was staying nearby with her family at the Rose Hotel. After George Warren Dresser graduated from the United States Military Academy and posted at Fort Adams outside Susan’s home of Newport, he pursued his love. It was not an easy road.

The Fish-LeRoy family was exceptionally well known in New York circles where names carried the weight of history and bore the shackles of expected romantic pairings. First, middle, last, and family names were shuffled around from generation to generation—perpetually recombining DNA of societal rank—so that they would always be a part of one’s title, ensuring that even the smallest link to storied heritage was immediately evident upon one’s first introduction. Fish . . . LeRoy . . . King . . . Schermerhorn . . . Stuyvesant. Edith’s mother had bestowed upon Edith a middle name taken from the surname of their ancestor, the famed Dutch governor Peter Stuyvesant. It would serve Edith in future times when money could not.

Edith’s father was a congenial, accomplished, and educated man with an honorable if humbler background than that of her mother. George Warren Dresser was of New England stock, educated at Andover, and hailing from a line of teachers, farmers, and lawyers. Edith’s grandfather Daniel LeRoy did not consider him an appropriate match for Edith’s mother and objected vocally and often to George and Susan’s union. But her mother’s older sister, Aunty Mary King—who herself had made a predictably wealthy yet loveless match—stood firmly on the Dresser side of love. Aunty King welcomed George into her home in Newport, where he was free to call on her sister. Hearts won out. In April 1863 at Calvary Church in New York, a line of groomsmen in uniform stood proudly by as George Warren Dresser married Susan Fish LeRoy. Then George headed south to war along with classmates, volunteers, and countless immigrants just arrived from places like Ireland and Germany.

George rose from a second lieutenancy in the Fourth Artillery to major before the war ended. Along the way he fought in the Battle of Bull Run and commanded a company out of Chattanooga, Tennessee, where he played a vital part in securing federal supply lines against Confederate attack. Once the war ended, George’s accolades mattered little to Edith’s grandfather, who insisted his son-in-law resign from the military and give his daughter the opportunity to live a life more worthy of her bloodline.

George consented and began a career in civil engineering. He made friends easily, and acted as editor of the trade publication American Gas Light Journal. He had bright dark eyes, a barrel physique, and wore his hair parted down the middle with just the suggestion of a wave on each side. The lower half of his face was wreathed in the friendly muttonchops popularized by Civil War general Ambrose Burnside. George welcomed all into his home—the children of friends, army comrades, gas workers. Edith’s mother was more soft-spoken, attentive to her children, skilled with a needle and thread, and purposely eschewed much of the life laid out for her. She loved her George dearly.

Of any residences in New York or Newport, the one perhaps most deeply etched in the minds of the Dresser children was the house at 35 University Place. The salon on the front of the three-story home provided young Edith and her sisters a view through a French window of Manhattan life outside. Sitting among the brocade surroundings they watched the horse-drawn streetcars passing by. The sisters competed to see who could most quickly identify the car numbers as the vehicles made their way north in the direction of Times Square, hauled by a few of the hundreds of thousands of horses that powered the city’s transportation, baptizing its streets with their urine and fertilizing whatever weeds managed to sprout between pavers with their manure.

In the back of the house, a glass conservatory overlooked the yard. From this vantage point, young Edith, all gangly legs and long, bone-straight hair, could keep an eye on her nineteen turtles. She watched as they basked happily within their shells in a warm spot, dove deep under the soil and brush to hibernate for the winter, and erupted from the earth for another season in the sun. Edith shared a room on the second floor with her two older sisters. It had one row of beds with a small conservatory outside that normally remained empty, save for the time Edith was quarantined there during a whooping cough episode. The servants’ quarters were in the basement, where the children found an excellent roller-skating surface and there was always a soft perch for young Pauline atop warm, folded clothes.

It was a busy home, its halls reverberating with the broken English of French servants, the laughter of children, and the rumblings of adults at backgammon or immersed in conversation in the red library. Edith’s brother, LeRoy, entertained friends in his domain on the third floor. George and Susan had visitors as well, even if the calendar of social events that regulated their world held little appeal for Edith’s mother, who preferred to stay at home close to her children. Sunday evening suppers were for stewed oysters and roast chicken, often set upon a red tablecloth in the dining room. On Sunday, supper was eaten early—a high tea, as it was then called—and on those evenings Edith’s father went to serve as a vestryman at Trinity Church’s St. John’s Chapel on Vesey Street. It took several transfers to arrive there by horsecar, but once in the hallowed space, the children watched as their father passed the collection plate among the pews.

In January 1883, the Hazelton Brothers piano factory across the street at 34–36 University Place erupted in flame. Servants and parents bundled the family’s possessions into balls of sheets away from windows before the glass panes burst from the waves of heat emanating from the burning building. Once the flames subsided the Dressers were fortunate that their home survived relatively unscathed. Yet they did not avoid all tragedy.

Edith’s mother had become ill during a recent trip to Europe. Her condition was worsening, and it prevented her from presenting Edith’s sister Susan, then eighteen, to society. Luckily, her mother’s friend Mrs. John Jacob Astor stepped in to help Susan along—a lovely gesture by a formidable doyenne of society. Still, months of increasing silence fell over the once lively household. Spring came and Edith’s sister Pauline moved into the bedroom with her older sisters. Nurses arrived. Adults demanded quiet. Doors shut the inevitable from Edith’s view.

One morning that April, the doors and windows of her mother’s room were opened. The lifeless shell that was Edith’s mother remained for the time being. Mourners and friends came and went. Edith went with Mrs. Woodworth, a family friend, to the clothiers Arnold Constable, where she was fitted for an appropriate outfit of black crepe to wear to her mother’s service at Trinity. Edith’s sister Susan fainted at the church.

Edith and her family could see that George’s health was also waning. Still mourning her mother, Edith was faced with losing her father as well. Knowing the children would soon be orphaned, Edith’s Aunty King offered to take Natalie to live with her. George begged his sister-in-law to keep the children together once he was gone, and Aunty King was soon called upon to keep her word. Edith’s father died a little over a month after his wife. His funeral was held on a day best befitting his honorable career in the military—Decoration Day. Edith’s parents were interred beside each other in the Newport cemetery. Edith was not yet ten years old.

Shortly after, Edith and her siblings went to Newport for what would turn out to be a lengthy stay. Her grandmother and that same, stern grandfather, the man who had frowned on his daughter’s marriage to a New England army officer, took the children in. Daniel LeRoy was already eighty-five years of age, and Edith’s grandmother was seventy-eight. The following year, 1884, he built a two-story addition onto the old red house at 206 Bellevue Avenue in Newport to accommodate his younger family members.

Grandfather passed away in 1885 at the age of eighty-seven, just two years after Edith’s parents, his mind having departed well in advance of his body. Now, in 1888, Grandmother was bringing the Dresser brood back to New York. As another winter in the city ended, spring brought the emergence of shoots from age-old trunks, no one knowing which branches might cross and when, bending to the will of the wind.

· · ·

That was also the year that another, more prominent, Manhattan resident had grown tired of New York winters and decided to make a change.

In 1888, George Washington Vanderbilt was twenty-five years old. As the youngest child of William Henry Vanderbilt and grandson of the infamously cutthroat tycoon Cornelius “Commodore” Vanderbilt, George may have wanted for nothing financially, but that hardly meant his life was void of all expectation. Quite the contrary. To be a son of the Vanderbilt dynasty was to have your every move, dalliance, chance encounter, and passing venture watched and analyzed, whether via opera glasses across the expanse of the Metropolitan Opera or by eager eyes scanning the society pages of the newspapers.

His grandfather Cornelius Vanderbilt had known much simpler times. Born in 1794, Cornelius had grown up on a farm on Staten Island, where the Vanderbilt family—or van der Bilt or van Derbilt, depending on who was signing their name—had lived for more than a century. His ancestors had seen Dutch rule pass to the English and then, finally, the birth of the American colonies. Through all the changing of guards and flags, many of the family continued to dwell within a world of their home country’s language and religion. Though their farms expanded and the number of Vanderbilts multiplied, work remained arduous and compensation scant. Uneducated in the traditional sense, and lacking in the most common of courtesies, young Cornelius was a diligent worker. Whatever he lacked in finishing he made up for in grit and ambition. As the most popular version of the story goes, during Cornelius’s youth, his mother, Phebe, offered him $100 to clear some acreage on the family land. Once the task was completed, Cornelius used those earnings to buy what the Native Americans in the region called a piragua. This “perry auger,” a ramshackle boat, gave Cornelius access to the waters surrounding Staten Island, the s...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherAtria Books

- Publication date2018

- ISBN 10 1476794057

- ISBN 13 9781476794051

- BindingPaperback

- LanguageEnglish

- Number of pages416

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

The Last Castle The Epic Story

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in good condition. Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00070186595

Quantity: Over 20 available

The Last Castle The Epic Story

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00077018828

Quantity: 20 available

The Last Castle: The Epic Story of Love, Loss, and American Royalty in the Nation's Largest Home

Seller: Gulf Coast Books, Memphis, TN, U.S.A.

paperback. Condition: Good. Seller Inventory # 1476794057-3-28054110

Quantity: 2 available

The Last Castle: The Epic Story of Love, Loss, and American Royalty in the Nation's Largest Home

Seller: Orion Tech, Kingwood, TX, U.S.A.

paperback. Condition: Fair. Seller Inventory # 1476794057-4-29044048

Quantity: 1 available

The Last Castle: The Epic Story of Love, Loss, and American Royalty in the Nation's Largest Home

Seller: Zoom Books Company, Lynden, WA, U.S.A.

Condition: good. Book is in good condition and may include underlining highlighting and minimal wear. The book can also include "From the library of" labels. May not contain miscellaneous items toys, dvds, etc. . We offer 100% money back guarantee and 24 7 customer service. Seller Inventory # 5AAWX70013WF_ns

Quantity: 2 available

The Last Castle The Epic Story

Seller: SecondSale, Montgomery, IL, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Item in very good condition! Textbooks may not include supplemental items i.e. CDs, access codes etc. Seller Inventory # 00073077955

Quantity: 2 available

The Last Castle: The Epic Story of Love, Loss, and American Royalty in the Nation's Largest Home

Seller: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.1. Seller Inventory # G1476794057I3N10

Quantity: 1 available

The Last Castle: The Epic Story of Love, Loss, and American Royalty in the Nation's Largest Home

Seller: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.1. Seller Inventory # G1476794057I4N00

Quantity: 17 available

The Last Castle: The Epic Story of Love, Loss, and American Royalty in the Nation's Largest Home

Seller: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.1. Seller Inventory # G1476794057I4N00

Quantity: 17 available

The Last Castle: The Epic Story of Love, Loss, and American Royalty in the Nation's Largest Home

Seller: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, U.S.A.

Paperback. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 1.1. Seller Inventory # G1476794057I3N00

Quantity: 7 available