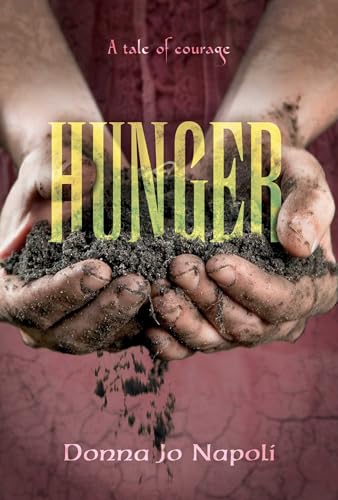

Items related to Hunger: A Tale of Courage

Synopsis

“The first-person narrative portrays Lorraine’s family and community with realistically drawn personalities and relationships as well as fine-tuned ethical dilemmas, while sketching in the backdrop of the wider catastrophe. A moving personal story.” —Booklist (starred review)

“Napoli skillfully evokes Lorraine’s close-knit community, interweaving elements of Irish culture, history, and land- and seascape in ways that make the story accessible and appealing...a timely reminder about conditions in our current world.” —The Horn Book

Through the eyes of twelve-year-old Lorraine this haunting novel from the award-winning author of Hidden and Hush gives insight and understanding into a little known part of history—the Irish potato famine.

It is the autumn of 1846 in Ireland. Lorraine and her brother are waiting for the time to pick the potato crop on their family farm leased from an English landowner. But this year is different—the spuds are mushy and ruined. What will Lorraine and her family do?

Then Lorraine meets Miss Susannah, the daughter of the wealthy English landowner who owns Lorraine’s family’s farm, and the girls form an unlikely friendship that they must keep a secret from everyone. Two different cultures come together in a deserted Irish meadow. And Lorraine has one question: how can she help her family survive?

A little known part of history, the Irish potato famine altered history forever and caused a great immigration in the later part of the 1800s. Lorraine’s story is a heartbreaking and ultimately redemptive story of one girl’s strength and resolve to save herself and her family against all odds.

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

About the Author

Donna Jo Napoli is the acclaimed and award-winning author of many novels, both fantasies and contemporary stories. She won the Golden Kite Award for Stones in Water in 1997. Her novel Zel was named an American Bookseller Pick of the Lists, a Publishers Weekly Best Book, a Bulletin Blue Ribbon, and a School Library Journal Best Book, and a number of her novels have been selected as ALA Best Books. She is a professor of linguistics at Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania, where she lives with her husband. Visit her at DonnaJoNapoli.com.

Excerpt. © Reprinted by permission. All rights reserved.

Hunger CHAPTER ONE

GreenWe crested the hill and Da stopped. He slid his bulging sack on the ground, wiped his big palm down his mouth, and put his fists on his hips. The stony bunching in his cheeks that had been building up as we approached the top now melted smooth. The thumping of my heart suspended. Please please let it be good news. Da jerked his chin toward the fields below.

Oh, thank the heavens.

I swallowed, turned my head from Da, and dared to look down. Green. Green green green. As green as it had been this morning when we’d left here—a fond farewell—and now an even fonder welcome back in late afternoon. Lush Irish green, as Granny used to say. She said the green of forests like the one we stood in now and the green of pastures beside the long, long road going north and south—the road I’d traveled only into town, but never beyond—that green helped her not to grieve the green of the sea way past that field to the west. The green she’d grown up with, but was too far from to see once she’d come to live with us. Ireland was green everywhere. And, best of all in this moment, the field below was green.

That field was healthy. Our spud field was still healthy!

Each day we worried anew, and each day it had stayed green. With any kind of luck, we’d have a good harvest this year. In another month, no more growling bellies. We’d be eating our fill.

Yes, it had been a grand Sunday after all, despite my initial disappointment. I had yearned to spend the day playing with the other children after church. But for the past two weeks, I’d had extra chores on Sunday, so it was pure stubbornness that made me allow myself to hope for a reprieve. Da was always finding new ways to earn a bit of money and lately he’d decided to pull me along. Today he’d even brought little Paddy. It was good, though, in the end it was good, because so long as the field stayed green, life would get better again. We kids would have plenty of Sundays to play.

“Look, Paddy,” I said, pointing to the Aran Islands, which were way off in the bay near Galways. This was the only point around here where you could get such a view. The islands were flat on top, as though the sea winds had worn them down. I imagined I could hear the wind blowing across those rocks—whistling secrets, howling sorrows.

“That’s where I lived as a boy. On the one called Inis Mór.” Da put his hand on top of little Paddy’s head. We both knew this, of course, but we nodded reverently all the same. “If you look hard, you can see the Cliffs of Moher beyond.”

Obediently, we stared southward. I’d never caught a glimpse of the cliffs before, and today was no exception.

“See? See that plume of spray there? That one, there? That’s the sea crashing against the cliffs.”

I leaned forward and concentrated. Sometimes I wondered if anyone could really see the spray or even the cliffs from here. But I didn’t question Da. He was proud of the fact that he’d visited those cliffs once upon a time. Maybe his pride gave him better vision.

I was proud too. Proud of being a daughter of this green land. I squeezed little Paddy’s hand in happiness, then dropped it and ran.

Rocks skittered out from under my bare feet. But I was deft; I wouldn’t go tumbling with them. It was heavy today, a dead day, the air wet from held-in rain for the third day in a row. I knew the temperature was low. But in the shimmer of all that green below, the day seemed absurdly and deliciously warm. The wind born from my own running cooled me in the loveliest way. I opened my mouth wide, to gulp the world.

“Owwww!”

Of course. I stopped and closed my eyes for a second—it didn’t serve anyone to show my annoyance—then went back and helped little Paddy up to sitting. Blood ran from a gash in his shin. Pebbles embedded there.

“Clean him up.” Da strode on past with a quick glance and playful tug at my hair. “Bold girl. Your ma’s going to be cross. You know your brother’s clumsy.”

“It’s not my fault! I didn’t tell him to run.”

“You ran,” Da said, not bothering to stop. “What did you think he would do? You’re bold, not thick. My strong, bold girl.” The sack of peat thumped on his back, but in a bouncy way, so I was sure he wasn’t cross, at least. He’d sell nearly all that peat in town—so that was good. And, most of all, no one could be cross so long as the field was green.

I looked around. The path here was lined with the occasional milkwort. I ripped off a stem and handed it to little Paddy. “Chew on this while I go find something to clean you up with.”

“Will it make it hurt less?”

I didn’t know about that. New mothers used milkwort to make their milk flow better. But I didn’t think little Paddy needed to hear that. I shrugged. “It might taste good.”

I scooted off through the brush and searched. The grasses here in this little stony meadow should have been stiff and rough this time of year. They should have scratched me raw. Instead, the few plants were soft, as though the earth was holding on to whatever wet it could. As I went farther, they got denser. A thin creek trickled along, making a whisper of a song. I hadn’t known it was there. I didn’t know these hills well. We children hardly ever wandered this far. It was only because of gathering the peat on the other side that we’d gone today. How sweet that stream made everything—not just the grasses, the air itself.

Peppermint grew along the stream’s edge. That was good for calming nausea, at least. And here were some lavender plants. Lavender was good for fending off pesky insects, like mosquitoes. I broke off some of each and dragged them through the creek water to get them clean. Oh. Oh, glory! Blackberry brambles hung over the water on the other side of the stream. They arced like huge, tangled claws of a devil monster, and they were laden with fruit. My stomach clenched in hunger.

I looked around. Nothing to carry them in.

I pulled my dress off over my head. I was really too old to go without clothes, and Ma would be beyond cross when I got home. But no one was likely to see me between now and then, so what did it matter? I picked as many berries as my dress could hold and hurried back to little Paddy with the precious parcel.

He sat on the path in the same spot, but with one hand high in the air now. He flapped it at me, nothing more than a movement of the wrist, but I recognized it as a warning. His eyes were big and he slowly turned his head to look from me to something at his other side. I stepped softly toward him, half alarmed.

A huge blue underwing moth crawled along little Paddy’s outstretched leg. It was big as a bat. Dusk was still at least an hour off; that moth shouldn’t have been out and about yet. I hardly breathed as I set down my parcel. I peeled open the sides and took out two blackberries. I placed them on my tongue and shut my mouth, careful not to crush them. Then I got on all fours and crept the rest of the way to little Paddy. The moth paid me no attention. I took a berry from my tongue and extended my hand, slowly, slowly, and put the berry on little Paddy’s leg, in the moth’s path. I took the other berry and put it in little Paddy’s open mouth.

“Blasta—tasty,” he said softly.

The moth touched the blackberry tentatively with featherlike antennae. All at once his silver-gray wings shot open, exposing the glorious lilac blue beneath. Little Paddy reached out his hand to pet it, and the moth flew. My heart fell. But the moth circled and landed back again, on little Paddy’s head. Little Paddy laughed and the moth flew again. Away now.

“He was blue like smoke.”

“Mmm,” I said. I plucked the blackberry from little Paddy’s leg and ate it.

“Blackberries are so good,” said Paddy.

“They are, aren’t they?”

“Lorraine?”

“What, Paddy?”

“I’m sorry I got you in trouble.”

“Da wasn’t really cross.”

“He sounded cross.”

“Watch the set of his shoulders, the way he walks—they give him away.” I filled little Paddy’s hand with blackberries. “He’s happy really.” I almost added that Da would be happy so long as the fields were green and the spuds were coming, but I caught myself in time. Who knew what little Paddy understood at his age? “Look out to the side and suck on your berries. And if it hurts a lot, sing with me.”

Little Paddy put a berry in his mouth and dutifully stared to his side.

“On the wings of the wind,” I sang, as I picked each pebble from his gash, “o’er the dark rolling deep, angels are coming to watch o’er thy sleep.”

“I’m not going to sleep,” said little Paddy. “And that hurts a lot. Besides, you sing all ugly.”

“Just sing with me, you hear?”

“Angels are coming to watch over thee,” we sang, “so list to the wind coming over the sea.”

I rubbed the wound clean with the wet lavender. Then the peppermint.

“That’s not making it feel better.”

“But it makes you smell better.” I laughed. “You’re like some English lady’s garden now, hidden on the other side of a wall, but fragrant for all.”

“I’m cold.”

So was I all of a sudden. The weather had been like this lately, warmer in the day, sometimes nearly hot, then shivery at night. I wished I could put my dress back on. “The sun’s going down. We can’t dodder.”

“It’s getting fierce. Carry me.”

“I’ve got the berries to carry.”

“I’ll carry the berries. You carry me. Please, Lorraine.”

I closed up the parcel and handed it to him. “Don’t squish them, you hear?”

“I used to carry eggs all the time. When we still had hens.”

“Berries ruin far easier than eggs.” I turned and bent my knees.

Little Paddy climbed onto my back. Then he perched the parcel on top of my head.

“Don’t be thick, Paddy. It’ll fall off.”

“I’ll hold it there. Like the moth.”

That made no sense. But lots of things little Paddy said didn’t make sense. I tramped along down the hill.

“Let’s pretend it’s spud-planting time again, Lorraine. You know, let’s chant the rules like we did then.”

So spuds were on his mind too. I hoped he was just remembering our spring—not really worrying. I worried enough for both of us. “Smash those seashells,” I said.

“Smash! Smash! Smash!” Little Paddy wriggled on my back. I thought about him swinging the hammer in March. He was better at it this year. Most of the shells were reduced to grit. “Ready!” he shouted.

“Add water to the pig manure. Three parts water, one part manure.”

“Stir! Stir! Stir!” shouted Little Paddy. He was practically bouncing on my back, and well he should be. That manure gave the mixture exactly the nutrients spuds needed.

“Now add the smashed shells,” I said.

“Dump! Dump! Dump!” shouted little Paddy. “Stir! Stir! Stir!”

“It’s time,” I said. “Mind the line.”

“The line! The line!” he shouted.

I marched very straight as though I was following one of the long lines Da made in the field with the spade. “Throw it!” I said.

“There! There! There!”

I felt his little body twist, and I knew he was pretending to throw handfuls of the crushed seashells and manure mix onto the grass on either side of the spade line. I grasped his legs tighter. “Throw it thick,” I chanted.

“There! There! There!”

“Turn the sod,” I chanted.

“Turn! Turn! Turn!”

Little Paddy hadn’t really ever helped with this part of the spud planting. But he had stood beside us this spring as Da and I did it. I remembered how my arms ached at the end of the day, how my back and neck and legs ached. Turning the sod over onto the mix of manure and shells was the hardest work ever. Harder even than digging for spuds in the autumn.

“Now, see how that turned-over sod makes such a lovely incubator for the seed spuds? It’s grand!”

“Grand!” shouted little Paddy.

“You’re a good help, Paddy. The best. So you can have the best treat of all. You get to put in the seed spuds.”

“Hurrah!” shouted little Paddy. “Shove! Shove! Shove!”

I remembered his skinny arms pushing those little spuds into place. I remembered all our hopes as the pile of seed spuds gradually disappeared.

I marched ever more happily now, the rest of the way down the hill and past the fields, all the way home to our stone cottage. A wiggly brother on my back, and a green, green world. What could be better?

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherSimon & Schuster/Paula Wiseman Books

- Publication date2018

- ISBN 10 1481477498

- ISBN 13 9781481477499

- BindingHardcover

- LanguageEnglish

- Number of pages272

- Rating

Shipping:

FREE

Within U.S.A.

Buy New

Learn more about this copy

Shipping:

US$ 2.64

Within U.S.A.

Top Search Results from the AbeBooks Marketplace

Hunger : A Tale of Courage

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Former library book; may include library markings. Used book that is in excellent condition. May show signs of wear or have minor defects. Seller Inventory # 17170120-6

Quantity: 3 available

Hunger : A Tale of Courage

Seller: Better World Books, Mishawaka, IN, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Used book that is in clean, average condition without any missing pages. Seller Inventory # 16540504-6

Quantity: 1 available

Hunger: A Tale of Courage

Seller: GF Books, Inc., Hawthorne, CA, U.S.A.

Condition: Very Good. Book is in Used-VeryGood condition. Pages and cover are clean and intact. Used items may not include supplementary materials such as CDs or access codes. May show signs of minor shelf wear and contain very limited notes and highlighting. 0.78. Seller Inventory # 1481477498-2-3

Quantity: 1 available

Hunger: A Tale of Courage

Seller: ThriftBooks-Phoenix, Phoenix, AZ, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.75. Seller Inventory # G1481477498I4N10

Quantity: 1 available

Hunger: A Tale of Courage

Seller: ThriftBooks-Reno, Reno, NV, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.75. Seller Inventory # G1481477498I4N10

Quantity: 1 available

Hunger: A Tale of Courage

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Good. No Jacket. Former library book; Pages can have notes/highlighting. Spine may show signs of wear. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.75. Seller Inventory # G1481477498I3N10

Quantity: 1 available

Hunger: A Tale of Courage

Seller: ThriftBooks-Atlanta, AUSTELL, GA, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.75. Seller Inventory # G1481477498I4N10

Quantity: 1 available

Hunger: A Tale of Courage

Seller: ThriftBooks-Dallas, Dallas, TX, U.S.A.

Hardcover. Condition: Very Good. No Jacket. Former library book; May have limited writing in cover pages. Pages are unmarked. ~ ThriftBooks: Read More, Spend Less 0.75. Seller Inventory # G1481477498I4N10

Quantity: 1 available

Hunger: A Tale of Courage

Seller: Books From California, Simi Valley, CA, U.S.A.

hardcover. Condition: Good. minor wear and creasing. Seller Inventory # mon0003483162

Quantity: 1 available

Hunger: A Tale of Courage

Seller: Books Unplugged, Amherst, NY, U.S.A.

Condition: Good. Buy with confidence! Book is in good condition with minor wear to the pages, binding, and minor marks within 0.78. Seller Inventory # bk1481477498xvz189zvxgdd

Quantity: 1 available