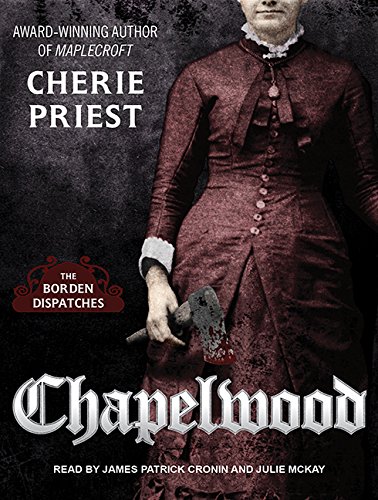

Items related to Chapelwood: The Borden Dispatches (Borden Dispatches,...

This darkness calls to Lizzie Borden. It is reminiscent of an evil she had dared hoped was extinguished. The parishioners of Chapelwood plan to sacrifice a young woman to summon beings never meant to share reality with humanity. An apocalypse will follow in their wake which will scorch the earth of all life.

Unless she stops it . . .

"synopsis" may belong to another edition of this title.

Leonard Kincaid, American Institute of Accountants, Certified Member

Birmingham, Alabama

February 9, 1920

I escaped Chapelwood under the cover of daylight, not darkness. The darkness is too close, too friendly with the terrible folk who worship there.

(The darkness would give me away, if I gave it half a chance.)

So I left them an hour after dawn, when the reverend and his coterie lay sleeping in the hall beneath the sanctuary. When last I looked upon them, taking one final glance from the top of the stairs—down into the dim, foul-smelling quarter lit only with old candles that were covered in dust—I saw them tangled together, limb upon limb. I would say that they writhed like a pit of vipers, but that isn’t the case at all. They were immobile, static. It was a ghastly, damp tableau. Nothing even breathed.

I should have been down there with them; that’s what the reverend would’ve said if he’d seen me. If he’d caught me, he would’ve lured me into that pallid pile of flesh that lives but is not alive. He would have reminded me of the nights I’ve spent in the midst of those arms and legs, tied together like nets, for yes, it is true: I have been there with them, among the men and women lying in a heap in the cellar. I have been a square in that quilt, a knot in that rug of humanity, skin on skin with the boneless, eyeless things that are not arms, and are not legs.

(I dream of it now, even when I’m not asleep.)

But never again. I have regained my senses—or come back to them, having almost fled them altogether.

So what sets me apart from the rest of them, enthralled by the book and the man who wields it? I cannot say. I do not know. I wanted to be with them, to be like them. I wanted to join their ranks, for I believed in their community, in their goals. Or I thought I did.

I am rethinking all the things I thought.

I am fashioning new goals, goals that will serve mankind better than the distant, dark hell that the reverend and his congregation seek to impose upon us all. They taught me too much, you see. They let me examine too many of their secrets too closely, and taste too much of the power they chase with their prayers and their formulas.

When they chose me for an acolyte, they chose poorly.

I take comfort in this, really I do. It means that they can misjudge. They can fail.

So they can fail again, and indeed they must.

In retrospect, I wish I had done more than leave. I wish I’d found the strength to do them some grievous damage, some righteous recompense for the things they’ve done, and the things they strive to do in the future. Even as I stood there at the top of the stairs, gazing down at that mass of minions, or parishioners, or whatever they might call themselves . . . I was imagining a kerosene lantern and a match. I could fling it into their midst, toss down the lighted match, and lock the door behind myself. I could burn the whole place down around their ears, and them with it.

(And maybe also burn away the boneless limbs, which are not arms, and are not legs.)

But even with all the kerosene and all the matches in the world, would a place so wicked burn? A place like Chapelwood . . . a place that reeks of mildew and rot, and the spongy squish of timbers going soft from the persistent wetness that the place never really shakes—how many matches would it require?

All of them?

I stood at the top of the stairs and I trembled, but I did not attempt any arson.

I did nothing bolder than weep, and I did that silently. I can tell myself I did something brave and strong, when I walked away and left them behind. I can swear that into the mirror until I die, but it isn’t true. I’m a coward; that’s the truth. I was a coward there at Chapelwood, and I am a coward every day I do not descend upon that frightful compound with a militia of righteous men and all the matches in the world, if that’s what it would take to see the place in ashes.

Not that I could muster any such militia.

Even the most righteous of men would be hard-pressed to believe me, and I can only admit that my case against the reverend may well sound like nonsense. But the strangeness of my message makes it no less true, and no less deadly. No less an apocalypse-in-waiting.

In time, perhaps, they will reveal themselves as monsters and the city will rise up to fight them. And the one thing working in my favor is that, yes, there is time. Their mechanizations are slow, and that’s just as well; what horror would the universe reveal if mankind could alter it with a whim and a prayer? No, they need time yet—time, and blood. So there is time for the men of Chapelwood to make a mistake, and I will be watching them. Waiting for them.

Stalking them, as they have stalked others before.

Which brings me to my recent resolution, and why I’m writing of it here.

Do I incriminate myself? Fine, then I incriminate myself. But I will incriminate the reverend, too. I will incriminate them all, and when my time comes, I will not go down alone. I will not go quietly. And I will not have the world believing me a fiend or a madman, not when I am doing God’s own work, in His name.

(If He should exist, and if He should see me—then He will know my heart, and judge me accordingly. I have tried to pray to Him, again and again. Or rather, I have tried to listen for Him, again and again. He does not speak to me, not so that I can hear it. It is one thing I envy the reverend and his followers: Their god speaks.)

(Or is their god the devil after all? For it is the devil who must make his case.)

This must be how the Crusaders felt, when tasked with the awful duty of war and conquest. A necessary duty, and an important one, to be sure. But awful all the same.

My duty is awful too, and I will not shirk away from it. I will confront it.

I said before that they showed me too much, and they did. They invited me into their confidence because of my training and my aptitude for numbers; I’ve always had a head for sums, and I’ve worked as an accountant for the city these last eleven years. They needed a mathematician, a man who could see the vast tables and workings of numbers and read them as easily as some men read music.

I was flattered that they considered me worthy of their needs. I was proud to assist them, back when I was weak and eager to please.

I took their formulas, their charts, and their scriptures, and I teased out the patterns there. I showed them how to make the calculations themselves, how to manipulate the figures into telling them their fortunes. I believed—do you understand? I believed that the reverend had found a way to hear God speaking, and that when He talked, He spoke in algebra.

I was right about part of it. Someone is speaking to the reverend in proofs and fractions, but it’s not the God of Abraham. I don’t know what it is, or what else it could be . . . Some other god, perhaps? Is that blasphemy? No, I don’t think so. It can’t be, because the first commandment said, “Thou shalt have no other gods before me.” It did not say there were no other gods; it said only to eschew them.

Would that the reverend had obeyed.

Would that I had figured it out sooner, that I was hearing the wrong voice when I scratched my pencil across the paper, tabulating columns and creating the tools the church would need to hear the voices of the universe without my assistance. It is not so easy to live, knowing that I may have given the reverend a map to the end of the world.

So I will do what I can to thwart him. I will take matters back into my own hands, and take the formulas out of my head and commit them to chalkboard, to paper, to any surface at hand, and I will beat them at their own game.

It won’t be any true victory on my part. Too many innocent people will die for this to be any great triumph of justice and virtue; and they will die at my hand, because if they do not . . . they’ll die at the hands of the church, and worse things by far will follow. So I am to become a murderer, of a man or two. Or three. Or however many, until the reverend makes enough mistakes and attracts enough attention that someone, somewhere, rises up to stop him in some way that I can’t.

Or else until he succeeds.

I must account for that possibility, and I will write it in as a variable, when I compile my equations and build my graphs. This string of numbers will haunt me until I die, or until we all do.

I have determined the reverend’s next target: an Italian woman who lives down by the box factory, and works there with her mother and sister. She is an ordinary woman, thirty years old and unmarried. Her hair is brown and her eyes are brown, too. She goes to Saint Paul’s on Sundays and Wednesdays, too, if her work and health permit it.

I will try to catch her on the way back from her confession, to leave her soul as clean as it can be. I will try to grant her that much, but if the reverend forces my hand, then I will have to take measures—so I can only pray that she prays, and prays often.

She’s done me no wrong, and her death will cause great sorrow, but it could be worse, and that’s what I must remember when I take my weapon and hide it in my coat. I must remember the equation written at the top of my slate in my hidden little flat, and I will tell myself as I strike that it is this woman tonight . . . or the whole world tomorrow.

It’s a terrible sum.

Father, forgive me—for I know precisely what I’m doing.

Ruth Stephenson

Birmingham, Alabama

September 4, 1921

(Letter addressed to Father James Coyle, Saint Paul’s Church, Birmingham, Alabama)

I’ve been thinking about what you told me, about demons and God and everything else we can’t see—but still take for granted. You can’t be completely wrong, and I know that for a fact because I’ve seen it myself, and I’m so afraid I just don’t know what to do. You don’t know my daddy, sir. You don’t know what he’s like, or how he gets.

You don’t know what he’s gotten himself into, but I’m going to try to explain it, and maybe you can help me . . . since you did offer to try.

It started back in January, when Daddy got caught pretending to be a minister so he could marry people, down at the courthouse. Our pastor saw him, asked what he was doing, and got a straight answer out of him, more or less. I’d give him credit for telling the truth except that he’d been caught red-handed, and he would’ve looked stupid for lying about it.

(Daddy hates looking stupid. I guess everybody does, but you know what I’m trying to say. He takes it personal when you call him out.)

So when Pastor Toppins caught him pretending to be something he wasn’t . . . they started arguing, and then before you know it, Daddy had to find a new church. He said he might as well make up his own church, if it was going to come to that, and at first, I thought that’s what he was planning. But then he got drinking and talking with some man from the True Americans, who said maybe we ought to try out the Reverend Davis’s new flock.

Daddy said no at first, because he ain’t no Baptist, but this fellow (I can’t think of his name, but it was Haint, or Hamp, something like that) said it didn’t matter, because it was supposed to be a meeting of like-minded men, and anybody who wanted to hear the word straight from the Bible with a patriotic Southern bent ought to come on out to Chapelwood for Sunday services.

I didn’t want to go, because I know what it means when somebody says “patriotic Southern.” That just means it’s made for angry white men, and to hell with everybody else, me included.

My daddy’s been angry and white his whole life, and it’s gotten him nothing but mean. It’s gotten me and my momma beat, and it’s gotten us broke, and it’s gotten him nice and drunk a whole lot—which gets him even more ornery.

And that’s about it.

But he made me and my momma go with him, out to Chapelwood where all the other angry men go. Some of their wives were there, too, but I didn’t see any children anyplace. Come to think of it, I was probably the youngest person there, and I’ll be twenty-one in August.

So we went, and I haven’t been able to shake the bad feeling it gave me ever since.

We rode up to the main house, or lodge, or whatever it is, in a cart because we don’t have a car, but that was okay with the reverend. He had somebody put our horse up, and greeted us warmly—like this was just any Sunday service—and I think Momma felt a little more at ease about it when she saw him acting like everything was fine.

The reverend was wearing all black, like you do . . . but it wasn’t like a priest’s black or a pastor’s black. It was something like a Klan robe, done up in black instead of white. It had this strange gold trim on it that almost made the shape of a star when he held still and it hung down off his shoulders. You couldn’t see his feet at all, and his hands were covered in black gloves—not leather riding gloves, but cotton, I think. Under those long arm sleeves, his hands looked strange. Like his fingers didn’t have any knuckles or joints . . . they moved like an eel moves, all smooth and just about boneless.

Please don’t read that and think I’m crazy.

He invited us up the stairs of that big building, I guess it was a house, come to think of it. Probably the biggest house I ever been inside in all my life—even though we didn’t see too much of it, just the church part in the front. It was shaped funny; it made me think of a cross between a castle and the courthouse. There’s lots of stone, lots of columns. Several towers. But it don’t look like a church, that’s what I’m saying. The stairs were wide but not too tall, and I had to make little tippy-toe steps to get up them without tripping myself. The whole thing was just so damn uncomfortable, if you’ll pardon me saying so. I knew it from standing outside, from pausing there and looking up—or from looking down at my feet, trying not to fall when I followed everybody up inside . . . that’s not a church, and it’s not meant to make people feel safe or comfortable. It’s not meant to be a friendly place that welcomes people from outside. It’s a prison, and it’s meant to keep people in.

I figured that out for sure once we went through the door. It was a little door, not something big and open that swings back and forth to let the spirit of God come and go with His people. And everything inside was dark. Not dark like your church, when the lights are down and all your candles are lit. That’s a warm, nice kind of dark, and I can still see where I’m going. In your church, there’s all that light from the colored windows, and it glitters off all the gold and the wood. Your church glows. This place . . . it didn’t give off light. It ate light.

When I was a little girl and I told my momma I was afraid of the dark, this was the dark I meant.

I couldn’t see my own two feet at first, when the door closed behind us. Hardly even my hands, if I waved them in front of my face. I blinked a whole lot, and after a few seconds I could see a bit, but I didn’t see nothing that made me feel any better about being there.

The pews and t...

"About this title" may belong to another edition of this title.

- PublisherTantor Audio

- Publication date2015

- ISBN 10 1494552477

- ISBN 13 9781494552473

- BindingMP3 CD

- Rating

(No Available Copies)

Search Books: Create a WantIf you know the book but cannot find it on AbeBooks, we can automatically search for it on your behalf as new inventory is added. If it is added to AbeBooks by one of our member booksellers, we will notify you!

Create a Want